COVID-19 Recovery series

As the country moves towards economic recovery from the pandemic, the Institute considers the policy choices ahead for Canada.

Preparing for the worst is a challenging balancing act. During a once-in-a-generation emergency, like we’re experiencing now, it’s reasonable to expect a well-designed emergency response system to be stretched near its limits. At the same time, if these systems are overwhelmed, the results can be catastrophic.

That understanding is driving Canadians’ collective efforts to flatten the curve of the COVID-19 outbreak — hopefully alleviating some of the pressure on our hospitals and health care systems in the short term to improve their capacity to address the crisis over time.

But when multiple sources of risk overlap and interact, responding effectively can be overwhelming. In the face of the COVID-19 crisis, other risks aren’t going away. In fact, as communities across Canada brace for potentially another season of floods, fires, and extreme weather events, the months ahead could underscore the challenges of preparing adequately for multi-dimensional risks — and the benefits of more comprehensive approaches to building resilience and reducing vulnerability.

Plan for the worst, expect…uncertainty

Many elements of emergency response systems in Canada will be stretched near their limit over the coming months because of COVID-19. Ontario has recently increased the amount of critical care ground ambulances in anticipation of resource needs. Canada created a database to help provinces and territories find individuals like retired nurses, paramedics, and emergency managers that could be pulled in to help. Many hospitals have stopped elective surgeries and restructured staffing to build surge capacity.

However, the challenge of planning for the worst in the context of profound uncertainty is not unique to the current crisis. Emergency managers have a mandate to assess the full landscape of risks and then plan accordingly. Further, they must not allow immediate threats to obscure longer-term vulnerabilities. Public Safety Canada encourages the use of ‘all hazard risk assessment’ tools to examine the breadth of risks that could be compounded, such as cyberattacks, wildfires, and earthquakes. This approach acknowledges that the greatest stresses happen when there are multiple events occurring at the same time which collide with long-term vulnerabilities.

That’s why, as governments across Canada scramble to navigate the current crisis, they also must keep an eye on the looming seasonal hazards that could further stress emergency systems.

Planning for the inevitable — and the unexpected

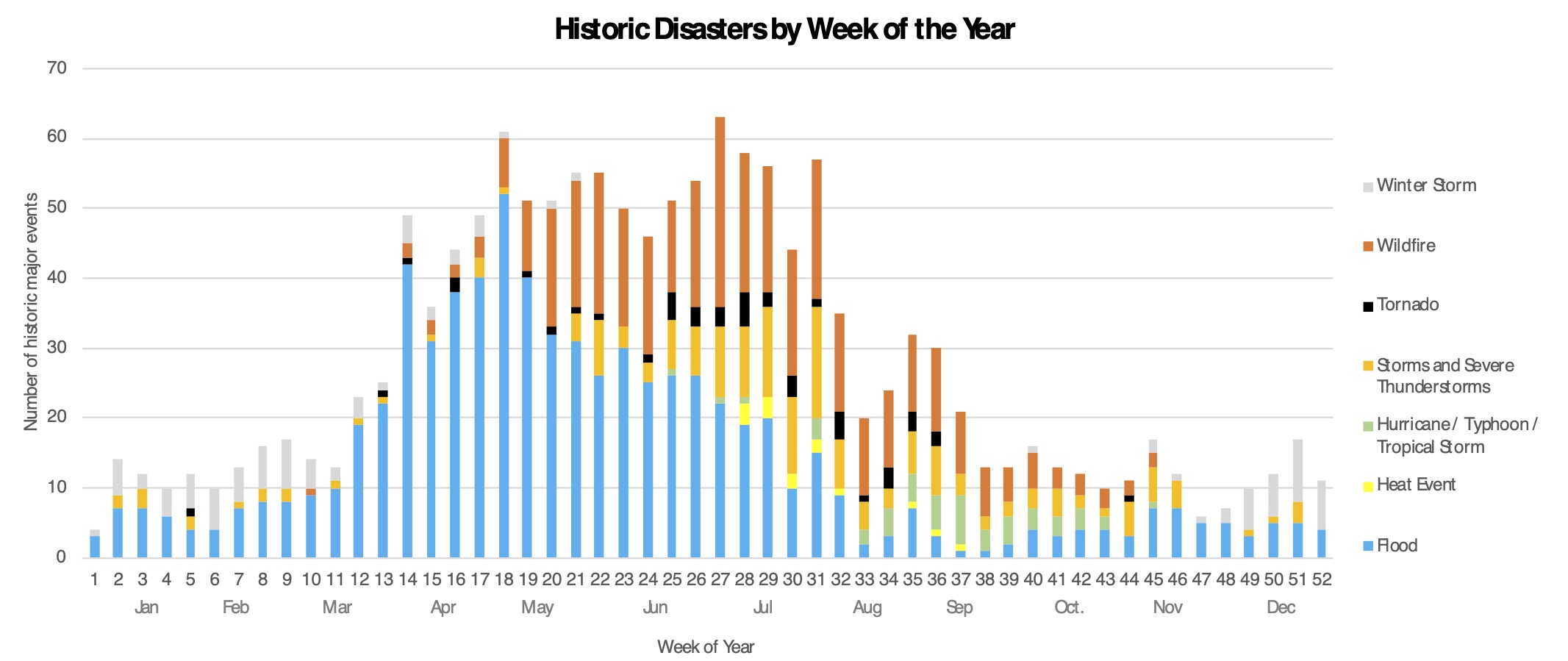

As many Canadians know all too well, some of the country’s major hazards – floods, wildfires, and severe weather — follow strong seasonal trends. The figure below illustrates the seasonal distribution of all disaster events in the Canadian Disaster Database from 1900 onward. It shows that, historically, the bulk of disasters in Canada occur between late spring and early autumn. And science indicates such events are likely to become more frequent and extreme as Canada’s climate changes.

This year is not shaping up to be an exception. As one indicator of potential spring flood risk, snowpack across British Columbia is above average this spring, with snowpacks in the Central Coast and Upper Fraser regions more than 130% of the historic average. Fire season in many regions has also just started, with seasonal crews begining work on April 1. Environment Climate Change Canada’s three month climate forecast shows a 60-70% probability of above-average temperature in Quebec – a potential indicator of quick snow melt and summer heatwaves.

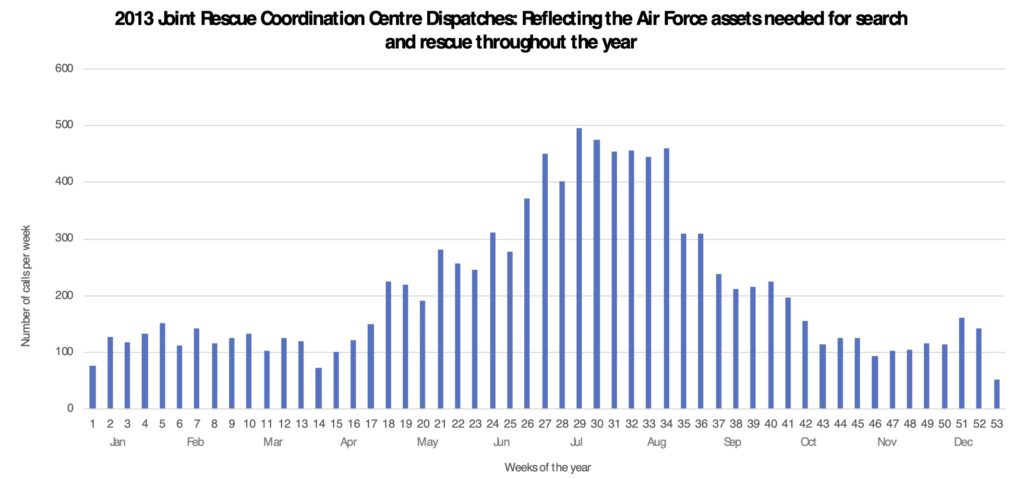

In light of the current health and economic crisis, disasters that will inevitably occur over the coming months will put additional pressure on emergency response and resource management. For instance, how will healthcare systems build additional capacity to respond to wildfire smoke and heatwave-related illnesses? How will the Department of National Defense allocate resources to balance search and rescue demands (which are likely to rise dramatically in the months head, as identified in Figure 2), flood and fire support, and potentially COVID-19 assistance?

Emergency response will also be constrained by the need for continued physical distancing and protection of first responders. How will individuals that are evacuated because of a flood or fire be sheltered while maintaining distance from one another? Where can wildfire crews stay if crowding them into temporary camps is a health concern?

Further, responding effectively to weather events is highly dependent on volunteers — who may not be able to help if they are infected by COVID-19 or in isolation. Recovery efforts also require trades and emergency repair work, mobilized by the insurance industry, to keep communities functioning after a disaster. If that support is not available due to COVID-19, it could be devastating.

The need to prepare isn’t limited to risks that that we know are on the horizon. As the world has now seen first-hand, even when emergencies like a global pandemic are anticipated, there’s no telling when it could hit. In the most un-probable and unfortunate confluence of events, what would happen if Vancouver was hit with ‘The Big One’ this year? Emergency managers and policy makers can rarely predict when exactly an event will happen or its magnitude, let alone how numerous risks will compound over time.

Building systemic resilience

Disasters can ripple through our society, highlighting systemic vulnerabilities. Amid the pandemic, for example, it’s evident that people without access to secure housing or adequate healthcare face additional challenges. The vulnerabilities of communities that do not have regular access to potable drinking water — including more than 60 on-reserve Indigenous communities — are compounded in an emergency that demands people shelter in place. An economy that has grown by drawing on household debt places families in a precarious place when jobs suddenly vaporize or when a disaster hits.

Resilience is not only influenced by sensitivities. Adaptive capacity is also a key factor. There are promising signs of hope here, with emergency response systems and society as a whole showing agility in reallocating and re-tooling resources—from recruiting retired medical staff to bolster capacity, or manufacturers reconfiguring their operations to produce much-needed equipment like ventilators.

In the coming weeks, continually increasing the agility of emergency systems will need to be a priority. And, in the months and years to come, as Canada rebuilds and heals, policy makers will likely need to further examine how systems are vulnerable in both the short term (e.g. severe wildfire season) and the long-term (e.g. permafrost thaw damaging homes across the North) while building effective policies to reduce and manage overlapping risks.

Not doing so leaves Canadians more vulnerable to the next “big one,” be it a new virus, a tsunami, the slow burn of climate change — or some combination of these threats at once. Fortunately, there is much to learn from the collective response to COVID-19 that could lead to better preparation and risk reduction in the future, including improved cooperation between different levels of government, and the ability to engage industry in responding in innovative ways to the challenges society faces.

After all, whether responding to a pandemic or addressing climate change, we’re all in this together.

COVID-19 Recovery – More of this series