When COVID-19 lockdowns started back in March 2020, Canadian streets and highways fell silent. Buses, trains, and trams ran empty. Non-essential workers stayed home. Our lives came to a standstill, in what now seems like a lifetime ago.

New cellphone data from Apple adds colour to our collective memories. It shows a near identical plunge in mobility across Canadian cities when the pandemic first struck. But as local and provincial economies gradually reopened, and as parts of Canada now battle a second wave of COVID-19, some interesting—and potentially worrying—trends are emerging that could have serious implications for Canada’s climate commitments.

Stay the blazes home!

Within a few weeks of the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a global pandemic in early March, every province and territory went into lockdown. What followed has become the greatest mobility experiment in Canadian history.

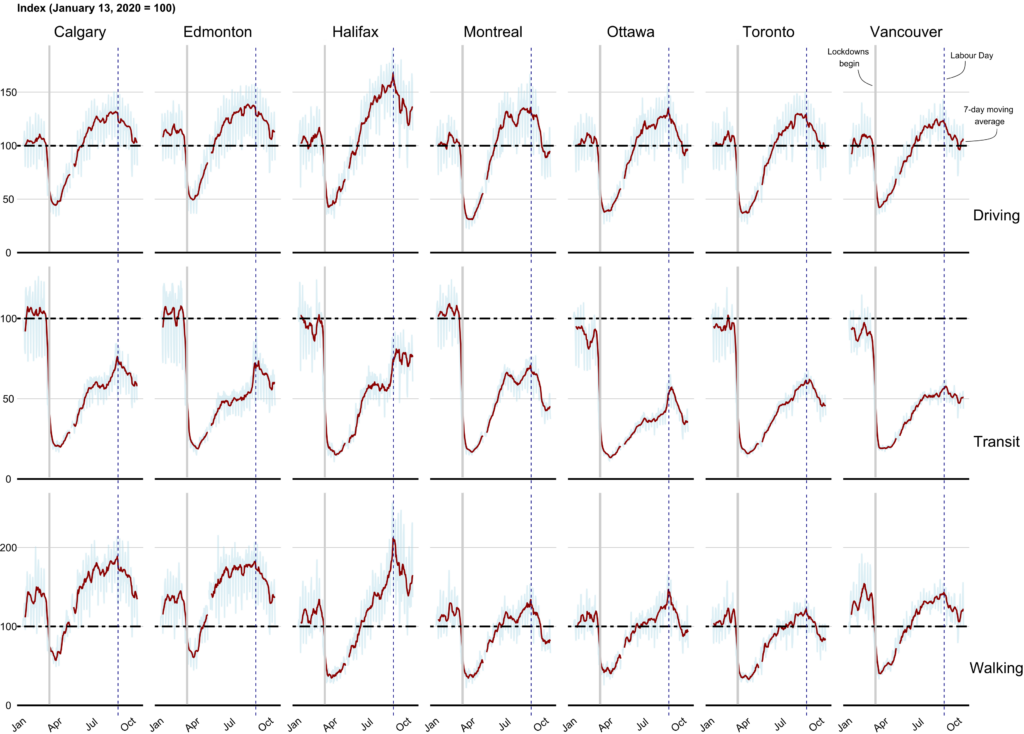

Using publicly available data from Apple (based on the volume of trip planning requests), the figure below shows mobility trends for driving, public transit, and walking in seven Canadian cities (cycling data is unavailable). The graphs are an index, showing how trends in each city and across each mode of transportation have changed relative to pre-lockdown levels.

Figure 1: The shape of lockdown and recovery from January to October 2020.

Click to enlarge graphs. Source: Apple mobility data, author’s calculations. Note that the red line represents the 7-day moving average of mobility trends. The solid grey line on each graph represents the week in March when lockdowns were first ordered. The dotted blue line shows the Labour Day long weekend.

Three big trends stand out from this data:

- More COVID cases and public health restrictions equals less mobility. While this trend shouldn’t surprise anyone, the data show how deeply mobility plummeted across Canadian cities as they went into lockdown. In Montreal, for example, driving levels in March fell by 78 per cent compared to January 2020. Mobility rebounded in the spring and summer months with lighter caseloads and fewer restrictions; however, it appears to be dropping again in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal as these cities battle a second wave.

- Driving rebounded strongly. As economies gradually reopened, driving rebounded faster than walking and public transit. In fact, driving exceeded pre-COVID levels in all seven cities profiled during the summer months and remains well above pre-COVID levels in Edmonton, Calgary, and Halifax. Some of this might be transit riders opting to drive or people driving locally during their summer stay-cations. The usual summer driving season also probably played a role: driving levels in all seven cities dropped after the Labour Day long weekend, when people typically return to their usual work/family flow.

- Public transit is reeling. Despite many cities offering free transit for the first few months of the pandemic, transit ridership levels fell as low as 12 per cent in Ottawa compared to the beginning of the year. Even after months of recovery, ridership levels in most big cities are around half of what they were before COVID. The one bright spot is Halifax, where ridership was at 75 per cent of pre-COVID levels in October (the city also happens to have an extremely low caseload, which speaks to point #1).

Transitory or permanent?

Whether these trends are a temporary blip or a fundamental shift in how we move will have big implications for Canada’s climate commitments: road transportation accounts for over one-fifth of all GHG emissions in Canada. More people working from home after the pandemic is over, for example, could mean fewer commuters and less driving. By one estimate, the world could save around 18 million tonnes of CO₂ each year by 2030 if 20 per cent of the global labour force worked from home one day a week (roughly Nova Scotia’s total emissions in 2017).

Canadian driving trends point to a more worrying trend. The quick rebound in driving demonstrates the allure of the automobile in a pandemic. In fact, many young people are considering buying their first car due to the pandemic (one author included!), while others consider cars the ultimate form of personal protective equipment. But a permanent uptick in driving would bring a host of problems with it: more greenhouse gas emissions, more congestion, more air pollution, more car-dependent sprawl, and more financial troubles for local transit agencies.

A sustained shift to more active transportation would help pull in the opposite direction, offering big climate and air quality benefits. Although cycling isn’t included in the data, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that people are biking more. Many bike shops have run out of inventory. The real test, however, is in the coming weeks as temperatures drop and whether people choose to drive or take transit instead of walking or cycling.

Better policy for better mobility

Building a transportation system consistent with our climate goals requires, in the words of the World Economic Forum, a “transportation transformation.” And it’s clear that governments have profound influence in shaping this future.

Helping transit agencies to improve service, accessibility, and health precautions, for example, can entice riders to return—critical to the financial and climate sustainability of Canadian cities. For those still set on buying a car and driving more, governments have a range of options to encourage climate-friendly cars and discourage congestion. And for active transportation, some cities are shutting down main arteries and replacing them with hundreds of kilometers of cycling infrastructure to accommodate the rapid rise in two-wheelers.

All of these policy actions could help steer trends in the right direction, but there’s little time to waste. The new habits we adopt as economies reopen (or close shut again) will become harder to break over time and could lock us into a future that is inconsistent with our climate goals and make it much harder to bend the emissions curve down. COVID-19 has sparked the greatest mobility experiment in Canada. Let’s make sure the results of this experiment work for our mobility and our climate.