Canada is heating up. Climate change is pushing temperatures to new extremes. Summers are starting earlier, and shattering temperature records every year. This means hotter days, hotter nights—and costly, sometimes deadly, impacts for people, communities, and the economy.

We live in a northern country, one that is cold in most places, for much of the year. But it’s time for Canada to get ready for extreme heat.

Extreme heat is dangerous

Extreme heat can have severe impacts on people’s health, particularly for those who are most vulnerable: elderly people, those living alone or on a low income, and those with chronic illnesses and mental health challenges. Studies put the global mortality rate associated with extreme heat at 5 million deaths per year. During the 2021 heat wave in B.C., 619 people died from heat-related causes as the temperatures climbed over six days. Ninety-three per cent of those who died did not have functional cooling in their homes.

How to adapt to extreme heat

Cooling off indoor areas with heat pumps or air conditioners is one of best ways to adapt to extreme heat.

Policy can help ensure people have access to effective and affordable cooling indoors. For example, starting in 2025, the City of Vancouver will require developers to include mechanical cooling in all new multi-family homes. The City of Hamilton has a bylaw in the works that will protect renters from extreme heat, requiring landlords to ensure apartments are kept at safe temperatures. And both Washington and Oregon have programs to help low-income and vulnerable people access grants to install mechanical cooling.

Painting the town green

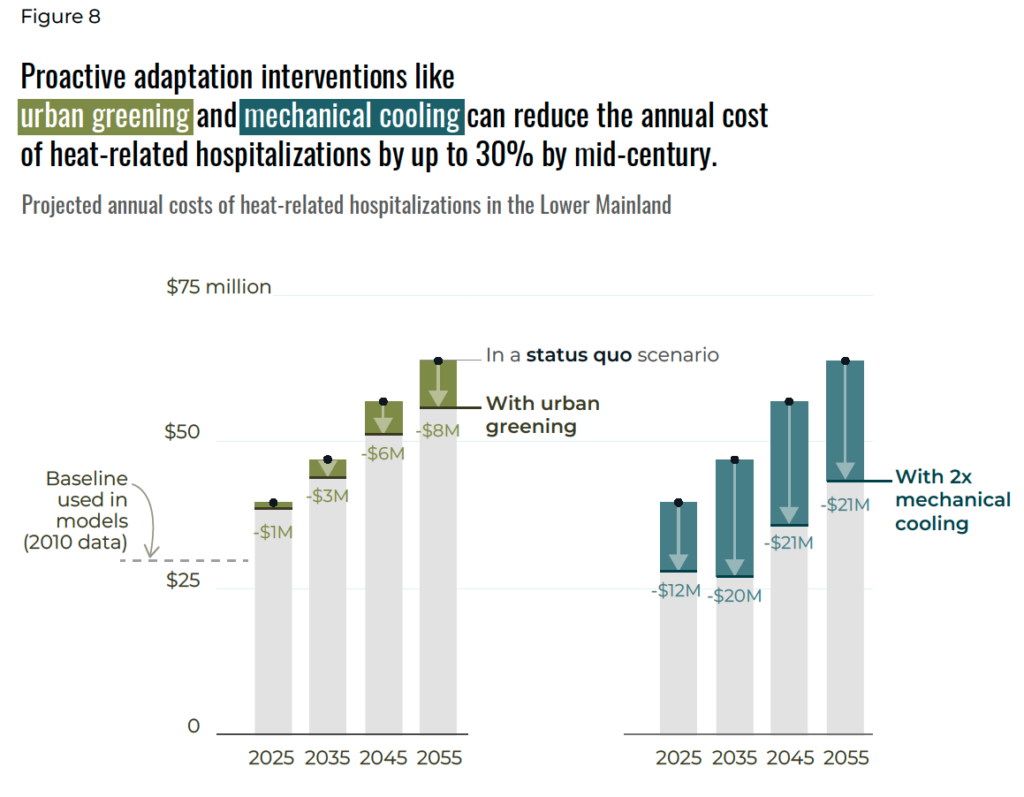

Urban greening initiatives such as green roofs and investments in tree planting can also protect people by keeping homes and workplaces cool and expanding shaded outdoor areas. Although these investments take time to pay off, urban greening and mechanical cooling together can reduce the impact of extreme heat on people’s health and the economy. Just in B.C.’s Lower Mainland, these two adaptations combined would reduce the cost of heat-related hospitalizations by up to 30 per cent by mid-century.

Keeping employers and workers informed

Few economic sectors are immune to the impacts of extreme heat. But not all sectors are prepared to deal with the impacts—particularly in regions that are less familiar with the impacts of extreme heat. Occupational standards that account for extreme heat and provide timely guidance to both indoor and outdoor industries can protect workers and minimize the economic impact that comes from labour disruption. In California, outdoor industries are required to have heat illness prevention plans and must provide employees with heat-illness training—similar requirements for indoor industries are also in the works. Public heat warnings in Europe weave in guidance for employees who are at risk of heat exposure. And in B.C. the government is providing public information on how to stay safe in extreme heat.

Getting the word out earlier that extreme heat is coming can also help keep people safe and reduce impacts. Currently, Environment and Climate Change Canada issues public heat warnings one to two days before an extreme heat event. In other jurisdictions, such as the United States, Europe, and Australia, public heat warnings are issued several days in advance. Earlier warnings allow more time for emergency responders, hospitals, citizens, and workplaces to prepare.

Finally, employers can also adapt workplace schedules to accommodate for extreme heat, to ensure people are not working during the hottest parts of the day. During the B.C. heat wave, tree fruit farms modified their harvesting time to after midnight to reduce heat stress on workers. This protects both employees and labour productivity. Adapting workplace schedules in B.C. could save $4 million per year in heat-related GDP losses by the 2030s.

Conclusion

Extreme heat is not a future threat—it’s already here and the impacts to people, communities, and the economy can be severe. It also has cascading impacts, contributing to wildfires and drought conditions that impact food systems and supplies, and putting further strain on healthcare staff, systems and resources. It’s time to prioritize adapting to extreme heat before the next heat waves hit. The safety, well-being and prosperity of Canadians from coast to coast to coast hangs in the balance.