As the world shifts to a low-carbon economy, protecting and assisting workers whose jobs are at stake is fundamental to a just transition.

Yet the policy blueprints so far in Canada—particularly just transition policies focused on workers affected by closing coal-fired power plants—are far too narrow for the challenges that lie ahead. Canada needs a much broader understanding of just transition that recognizes the full scale and scope of the transition ahead and integrates support for affected workers with clean growth and workforce resilience strategies. Indeed, this wider lens shows us that clean growth policies are the secret to a successful and just transition in Canada.

Let’s first explore why that wider lens is needed, and then look at what can be done to get just transition right.

Bigger than coal

A recent report by the Canadian Climate Institute, Sink or Swim, found that segments of the Canadian economy are deeply vulnerable to the global low-carbon transition that’s currently underway, and that concerted policy action is required to ensure the country’s prosperity in the coming decades as the world moves away from fossil fuels. Around 70 per cent of Canada’s goods exports are vulnerable to this transition, and those sectors employ over 800,000 Canadians—more than four per cent of Canada’s entire workforce.

The employment impacts of Canada’s coal phase out, by contrast, were orders of magnitude smaller, with only around 3,000 coal workers affected. Coal phase out is also primarily driven by domestic policy, while sectors such as oil and gas, iron and steel, and auto manufacturing are more vulnerable to global changes in policy, prices, or demand, meaning governments will have far less control over the timing of local impacts in globally traded sectors.

The scale of the challenge will also make some coal policies difficult to replicate. For example, if the federal government were to provide a per-worker equivalent to the $150 million infrastructure fund established to support economic diversification in impacted coal communities, it would require around $40 billion—a sum nearly 300 times larger. A similar focus on skills retraining may also miss the mark if overall employment in the region is declining, leaving slim pickings for alternative jobs.

It’s not just workers that will need a transition strategy—it’s entire regions, cities, and sectors

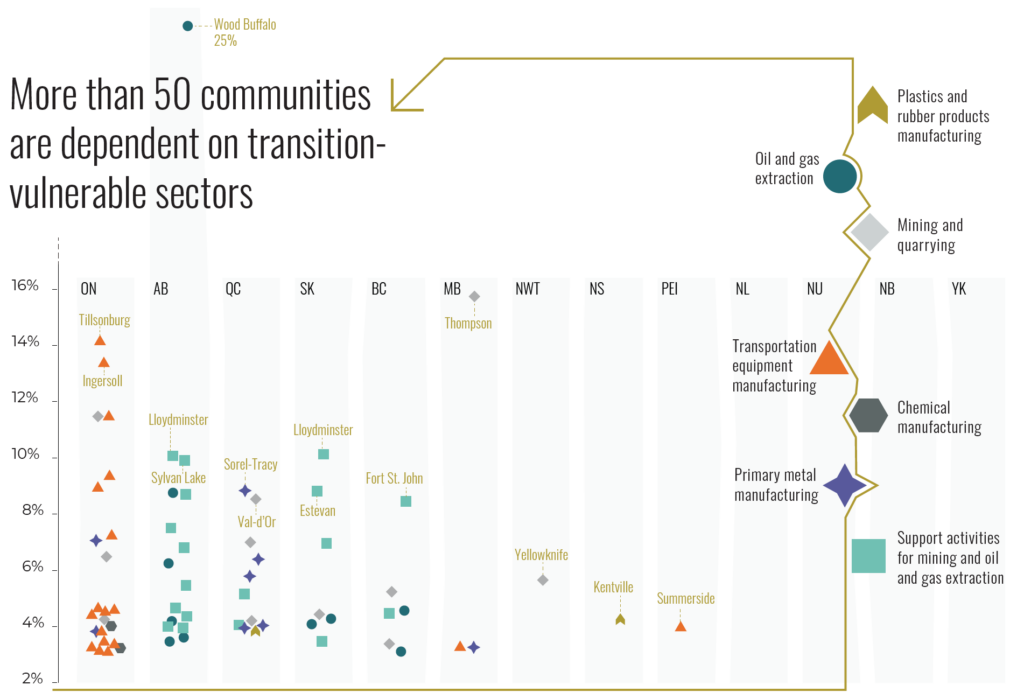

The Sink or Swim report found that the global low-carbon transition will affect sectors very differently, with some positioned to experience dramatic growth, others existential threats, and others still a complicated retooling. Emissions-intensive industrial sectors such as steel and aluminum, for instance, can succeed by becoming low-carbon leaders in their sector, while sectors such as oil and gas and traditional auto manufacturing are vulnerable to shrinking global demand for their product, requiring a shift into new business lines such as hydrogen and electric vehicles to remain viable. Smaller, rural communities are particularly vulnerable to broader employment impacts. The analysis finds dozens of cities and towns across the country that depend heavily on transition-vulnerable sectors. These communities tend to be less economically diverse and often have a harder time attracting new employers. The loss of an employer in a small community can have cascading effects, leading to layoffs in service industries such as construction, hotels, and restaurants. It can also lead to deteriorating fiscal health in local governments, which then leads to cuts in government services and employees.

Risks will also be unevenly spread across the workforce. Workers with less education will have a harder time finding new employment. Indigenous Peoples and visible minorities—who are overrepresented in many transition-vulnerable sectors—face greater barriers to employment that may mean market disruption hits them harder.

Just transition should be baked into clean growth strategies

Canada’s success depends on its ability to walk and chew gum at the same time: grow our economy while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The CEO of Teck Mining and chair of Canada’s business council has rightly argued that “Canada’s climate plan must be its economic plan, and Canada’s economic plan must be its climate plan,” but the devil, of course, is in the details. The Sink or Swim report highlighted some of the best strategies to integrate economic and climate plans: scaling up low-carbon companies to compete in growing global markets; decarbonizing emissions-intensive industries; and pivoting fossil fuel producers and auto manufacturers into new business lines. Growing investments in electric vehicle manufacturing, EV battery supply chains, net-zero chemicals and steel decarbonization are good examples of clean growth fueling a just transition.

However, where those actions take place—which regions, and which sectors—also matters. Thriving businesses and workers in one part of the country will not offset bankruptcy and layoffs in another part of the country. For the sake of social cohesion and Canadian well-being, governments at all levels should care about those that may be left behind in transition.

There are also people and communities that are not directly affected by transition that would see significant societal benefit from new economic opportunities arising from transition. This includes Indigenous communities across Canada, and communities struggling with high pre-existing levels of unemployment such as Cape Breton or many regions of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Incorporating just transition into clean growth strategies requires thinking as much about targeted local economic development and job creation as grand national goals.

Plan locally, support nationally

The scale and diversity of economic and workforce challenges, combined with limited government resources, mean that local and people-focused transition plans need to be combined with national, provincial, and territorial financial support and capacity.

Governments alone will not have sufficient financial resources to solve the just transition challenge—but can play a crucial role in mobilizing private investment. The EU, for example, developed a EUR 19 billion Just Transition Fund and loan facility to mobilize public and private finance for transition.

Transition plans can include efforts to understand and address barriers communities face to attracting investment and transitioning the workforce. In some cases, it may be a lack of enabling infrastructure (e.g., roads, internet access, electricity transmission). In others, it may be difficulty in accessing the capital needed to purchase an equity stake in a project or a lack of specialized skills. New Zealand, for example, developed a just transition forum that includes Indigenous leaders, employers, unions, governments, educational institutions, and community groups.

Finally, a renewed effort is needed to accelerate improvements in local and national workforce resilience. Better-financed programs that improve educational outcomes for vulnerable youth, expanded Indigenous Guardians programs that develop skills to care for lands and waters, and increased support for alternative education approaches can reduce the risk of worsening employment and poverty outcomes through transition. Universities and colleges need to adjust post-secondary programs to better reflect the skills Canadian companies will need to succeed through global low-carbon transition.

Canada will not achieve a just transition through a top-down plan. It needs to be driven from the bottom up, with substantial support from higher levels of government.

The big picture

How widely or narrowly governments interpret the meaning of just transition matters. A singular focus on current workers facing job risks could lead to plans that are unaffordable and missed opportunities to generate new sources of job growth.

A broader focus on clean growth strategies that drive localized transition-consistent job creation and prepare the workforce for the economy of the future can help avoid job loss concerns.

Canada has the potential to emerge from the global low-carbon transition with a stronger and more inclusive economy, but only if governments take a step back and see the forest for the trees. Just transition will be a whole lot easier if there are plenty of jobs to go around, in the places that need them. Clean growth may just be the solution governments are looking for.