[Click to see in English] ᐦᐊᑕᓯᓐ-ᒉᐃᒥᔅ ᐯᔨ ᓃᑖᓂᒡ ᐊᓂᑌᐦ ᐙᐸᓅᑖᑦ ᐊᣆᑌᐦᐁᕆᔦᐤ ᑳ ᐄᐦᑕᑣᐤ ᒌ ᐊᒋᔥᑖᐊᐸᔥᑖᐆᒡ ᐯᔭᒄ ᐊᓂᔫ ] ᒫᐆᒡ ᐁᐦ ᒦᔫ ᐋᐸᑕᓃᒡ ᐆᑕᐦ ᐊᔅᒌᒡ ᐁᐐ ᒥᔫᓈᑲᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᐊᔅᒌ ᓀᔥᑕ ᐁᐦ ᒥᔻᑲᒥᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᓂᐲ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒪᓯᐌᐦ ᒉᐦᒀᓐ ᐁᐦ ᐊᔫᔨᒪᑯᒡ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐊᔅᒌᒡ ᒉᒌ ᒥᔫᐸᐐᒡ ᐁᐦᐐ ᐊᑕᔥᑌᔨᑕᒥᒄ ᐃᔨᔫ ᐄᐦᑐᐎᓐ᙮ ᐆ ᓈᔥᒋ ᐁᐦ ᐊᒋᐦᐊᐸᐐᒡ ᐁᐦ ᐋᐦᒋᐸᐐᒡ ᐊᔅᒌ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᐁᐄᔥ ᐐᑕᒀᒡ ‘ᒪᔅᒉᒄ’ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᓂᑌᐦ ᐄᔥ ᓅᒋᒦᐦᒡ ᐁᐦ ᐐᒋᑣᐤ ᐆᒥᔥᑫᐦᒀᐤ ᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᓂᐲᐆᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᐁᐄᔥ ᐊᒋᔅᒉᔨᒫᑲᓅᑣᐤ ᑲᔦᐦ᙮ ᐆᔅᑌᐦ ᓂᔥᑕᒪᑎᓅ ᒦᓐ ᓂᔮᔪ ᒋᐦᐁ ᐱᓪᓕᔭᓐ ᐁᐦ ᐸᐸᒥᐾᑖᓄᒡ ᑳᐦ ᒥᔖᒡ ᒌᒫᓐ ᐁᐦ ᐋᐸᑕᓯᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐸᐦᑳᓂᔥᑖᑲᓅᒀᐤ ᒦᓐ ᐊᑕᑑ ᒥᓕᔭᓂᔅ ᒉᒌ ᔭᐆᒐᐸᐐᑖᑦ ᑳ ᒥᔖᒡ ᒌᒫᓐ ᒣᔑᑲᒻ ᐊᐦᐴᓂᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐆ ᐁᐃᔨᔅᐱᓇᑳᑦ ᐎ

The Hudson Bay and James Bay Lowlands of northern Ontario form one of the world’s most vital carbon sinks and life supporting areas, as an ecosystem of profound cultural importance. This vast landscape of peatlands, known in Cree as ‘muskeg’, is home to the Omushkego Cree, known as the water people. Storing over 35 billion tonnes of carbon, sequestering millions of tonnes more each year, this region is helping stabilize the global climate.

These lowlands are the homelands of the Indigenous communities that were signatories to Treaty 9. As the Omushkego people, they have stewarded the land for generations and maintain a deep spiritual and cultural connection to its rivers, wildlife, and muskeg. The region’s ecological wealth underpins traditional ways of life: it is a nursery for biodiversity, supporting threatened species like woodland caribou, wolverine, and sturgeon, as well as a sanctuary for hundreds of migratory birds. Protecting the Hudson—James Bay Lowlands is not only crucial for meeting climate goals and conserving biodiversity, but also for upholding Indigenous peoples’ rights and heritage.

Despite its global significance, this fragile region faces an unprecedented threat from proposed mining development in the area popularly known as the Ring of Fire. The Ring of Fire is the name mining companies have given to a sizable mineral deposit located in Treaty 9. With a lifespan of over 100 years, the proposed mining development will have negative impacts on the healthiness of nature and the ability of current and future generations to exercise Treaty and inherent rights, including rights to conserve and manage the land, and to hunt, fish, and trap.

In this context, the Indigenous grassroots have begun mobilizing to protect their homelands, asserting both environmental, inherent, and Treaty rights. One such grassroots group is the Friends of the Attawapiskat River (the Friends), a coalition of local community members dedicated to protecting the Attawapiskat River watershed from mining in the Ring of Fire. Their efforts highlight the critical need to amplify Indigenous grassroot voices and why honouring Treaty promises is inseparable from meeting climate and conservation goals.

Currently, the allowance of harmful mining practices discredits the Ontario provincial government’s ability to manage and regulate mining-related activities. This has led to calls for decisions to be Indigenous-led and respect the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), and numerous court challenges and rulings requiring mining regulators and governments to drastically improve current practices. Critical minerals for reducing fossil fuels are also located in other areas, not only within the pristine Breathing Lands.

The voice of the grassroots continues to grow in response to government and industry making plans made without proper Indigenous consent. The Friends have since become a leading grassroots voice on rights and climate action in the region. This case study, the quotes and reflections throughout, are from the Friends. Through outreach, ceremony, and advocacy, this case study is among the efforts the Friends are taking to work with allies to protect these peatlands and the rights of those who live downstream of the proposed Ring of Fire development.

This case study examines the Indigenous-led climate action in Treaty 9, focusing on efforts to protect the Hudson-James Bay Lowlands from Ring of Fire mining. It begins by detailing the background and context—the mining proposals, the ecological importance of the region, and the legal landscape—before analyzing how Indigenous communities are mobilizing on the ground and in policy arenas. It then outlines policy recommendations informed by this struggle, such as recognizing Indigenous Protected Areas and enforcing FPIC, and concludes with reflections on the broader significance of grassroots movements.

[Click to see in English] ᐆ ᑲᐐᔅᒃ ᐁ ᒥᓯᐌ ᐁᐦ ‘ᓈᓂᑑᐊᑰᑕᔥᑖᓄᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐁᐐ ᒦᔫᑲᓇᐙᐸᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᐊᓐ ᐐᔓᐌᐎᓐ ᐯᔨᑯᔥᑌᐤ ᐋᔅᒌᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᓂᐲᐦ’ ᐗᐦᑏᐌᐅ ᑖᓐ ᐁᐄᔥ ᐊᑯᔅᑖᑕᑲᓃᒡ ᐋᓂᑦ ᐁᐄᔥ ᓃᐴᑣᐤ ᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᐁᐦ ᓃᑳᓂᔥᒀᑲᓅᑖᐤ ᐊᑕᔅᒉᔨᑕᒨᐦᐄᐌᐅᓐ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐯᔭᑯᔥᑌᐆᔖᑉ ᐊᔅᒌᔫᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐄᔅᐸᐐᒡ ᒌᔑᒄ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᔅᒌ ᐁᐦ ᒫᔥᑖᓅᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᓈᔥᒋ ᐁ ᓂᑑᐌᔨᑕᒧᒃ ᒉ ᐋᐦᒋᐸᐐᒡ ᒉᒀᓐ ᐁᐄᔥ ᓂᓈᑲᑕᔥᑖᑲᓅᒡ ᐁᐦ ᓅᑲᑕᑲᓅᑦ ᐁ ᐊᒋᔥᑌᐃᑕᑲᓅᑦ ᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᐆ᙮

Through this in-depth exploration, this case study illustrates the critical role of Indigenous leadership in addressing climate change and environmental justice, and the urgent need for systemic change to respect Indigenous rights as a cornerstone to collective action for climate, conservation, and justice.

Background and context

Getting to know the Ring of Fire

More than 33,000 mining claims have been staked in a region dubbed the “Ring of Fire,” covering some 5,000 square km within Treaty 9 territory. Exploration permits granted by the province of Ontario, allowing for line cutting, drilling, and construction activities, are opening up this globally unique and intact peatland centred in the James Bay Lowlands. None of these claims and permits have been issued with the consent of the impacted and downstream Indigenous communities, which the Friends call home.

Spanning the coast of James Bays, the peatland (muskeg) of this region is an ecosystem of global importance. Its peat soils—some extending many meters deep—have accumulated over thousands of years, locking away billions of tonnes of carbon. By one estimate, the peatlands of the Hudson-—James Bay Lowlands contain up to five times as much carbon per square metre as the Amazon rainforest. In total, more than 35 billion tonnes of carbon are stored in these soils.

As long as the peatland ecosystem remains intact (wet and cool), this carbon is kept out of the atmosphere—effectively making the region a natural carbon sink, sequestering greenhouse gases that are vital for drawing down climate damaging emissions.

[Click to see in English] ᓇᒧᐎ ᒨᔥ ᒋᑲ ᒌ ᒨᔅᑳᑲᓀᐦᐁᓐ ᐆᑲᐐᒪᐆ ᐊᔅᒌ ᔔᔮᓐ ᐆᐦᒋ ᑖᐹ ᒦᓐ ᑳᐤ ᒋᑲᒌ ᐄᑕᑲᓐ ᐊᓐ ᒉᒀᓐ᙮’ – ᐯᔭᒃ ᐊᓐ ᑳ ᐊᐹᒡ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓐᐦ ᒌᐃᔥ ᐐᑕᒻ

You cannot keep digging up Mother Earth for a dollar because you’re digging up something that can’t be replaced.

– member of the Friends

Disturbing this landscape—by draining wetlands, digging them up, or subjecting them to extractive development—risks releasing that carbon, turning a globally significant carbon sink into a source of emissions. In the face of climate change, scientists and Indigenous land users alike warn that protecting these peatlands is critical to prevent climate-altering levels of carbon from being released. In other words, the fate of these Northern peatlands strongly impacts Canada’s ability to meet climate targets and reduce emissions by 40 per cent by 2030.

Beyond the climate regulation and stabilization the Hudson-James Bay Lowlands provides, it is also a rich habitat for wildlife and performs irreplaceable ecological functions. The peatlands filter water and sustain the health of the Attawapiskat, Albany, Winisk, and other great rivers that flow through this area and downstream to James Bay. This region is one of the last strongholds for Woodland Caribou in Ontario and supports other sensitive species such as the wolverine and polar bear at its northern edges. Countless migratory birds nest or stop over in the muskeg and coastal marshes—indeed the coasts of James and Hudson bays are globally significant breeding grounds for waterfowl and shorebirds.

Getting to know the legal landscape

Inaction by industry and governments to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) and respect Treaty promises is fuelling violations of Indigenous rights—from rights to clean water, free, prior, and informed consent, and conservation of nature. As Indigenous rights holders continuously struggle to access legal services so that they can document, raise awareness, and call for policy change in response to threats to their rights and interests, advancing access to justice has become critical to the Friends’ efforts to amplify grassroot voices.

In the context of the overlapping laws and jurisdictions impacting the Friends’ rights, as Indigenous and Treaty peoples, this section seeks to unpack a series of reforms in which the Friends have been directly involved and have advocated on behalf of in proposing a way forward.

International law and getting to “consent”

In 2016, Canada announced its endorsement to support the international United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) “without qualification” and to implement it. UNDRIP gives particular recognition to rights of Indigenous peoples over developments affecting them and their lands, their right to conserve and protect the environment and productive capacity of their lands and resources.

In 2021, the Canadian Parliament enacted the domestic United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People Act (UNDA) which affirms UNDRIP “as a universal international human rights instrument with application in Canadian law”1. The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) recently found that through the UNDA, UNDRIP is “incorporated into the country’s domestic positive law” and the Federal Court found that UNDRIP, as a “framework for reconciliation,” underscores the importance of “free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples to all decision-making processes that affect them.”

Among the obligations the UNDA imposes on Canada are to:

- affirm UNDRIP as a human rights instrument with application within Canada; and

- require the implementation of an action plan to achieve the objects of UNDRIP

Despite these recognitions and forward legal momentum, much work remains. As the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation, Pedro Arrojo-Agudo recently found extractive activities, including mining, continue to breach human rights, particularly the right to water of Indigenous People. In spring 2024, Mr. Arrojo-Agudo met with Indigenous representatives receiving compelling testimonies about harsh living conditions on reserve, where, in many cases, not even their human right to drinking water was guaranteed. The Friends met with Mr. Arrojo-Agudo in Ottawa during his Canadian tour and expressed that “people outside the community don’t understand the struggles we face as First Nations. Canada is a prosperous country but it feels like we’re still living in third-world conditions.”

As the Friends explained to the UN Rapporteur, without access to clean water, community members suffer from rashes and other skin-related issues. Threats of mining activities contaminating their rivers and muskeg (peatlands) further impact community members, inducing fear and anxiety. In recognition of these concerns, the UN Rapporteur stated, “Indigenous Peoples disproportionally face the brunt of risks of toxic water contamination with serious health impacts. It is regrettable that those who cause damage to or pollution of water sources are not being held accountable and required to compensate for the harms.”

Among the “deep reforms” recommended by the Rapporteur are laws that promote a human rights-based ecosystem approach, with equal participation of Indigenous Peoples and governments guaranteeing the principle of free, prior, and informed consent.

While these findings are directly applicable to Ontario, and the continued granting of mining claims and permits without the consent of Indigenous peoples, there remains no provincial law adopting UNDRIP and thus the role of it and UNDA is limited. While UNDRIP can be relied on to interpret existing law or aid in resolving ambiguities in statutory language, as a general principle of constitutional law, the federal government cannot make an international or federal law apply in an area of provincial jurisdiction. Instead, it is up to an individual province acting on its own behalf to implement a provincial law that would give effect to an international treaty, like UNDRIP. Therefore, while the UNDA and its accompanying action plan may provide helpful language and policy direction, advocacy is still needed for a provincial law which implements UNDRIP, for it to have a fully binding effect.

Impact assessment law and application to mining projects

Indigenous peoples, including the Friends, continue to vocalize the lack of meaningful consultation on extractive projects. Respecting Indigenous voices and communities, which stand to be most directly affected from the extractive industry’s legacy and new mining projects, means requiring the most robust of assessment processes—and one attuned to Indigenous laws.

There is space for this to occur, too, recognizing that the Impact Assessment Act (IAA) was written with UNDRIP in mind and its implementation is hardwired into its processes and decision-making. For example, the IAA requires consideration of Indigenous rights and Indigenous knowledge, and reaffirms Canada’s commitment to seek the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples in relation to decisions under the IAA.

Unfortunately, due to a “threshold” approach, wherein only mining projects of the most significant size are subject to an impact assessment (IA), it means the majority of mining projects—and their accompanying infrastructure, like smelters, are not subject to IA review2. This paucity in the application of law then removes the potential to advance Indigenous-led IAs, shared decision-making, and a mechanism that could facilitate the seeking of consent.

Concerns about the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC), a federal authority, have also been raised by the Friends, who have been vocal in pushing for Indigenous-led processes. Citing the need to build trust and have the requisite expertise and accreditation to truly undertake a process that respects Natural Law and Treaty, the Friends continue to advocate for the greater inclusion of Indigenous community members in IA processes.

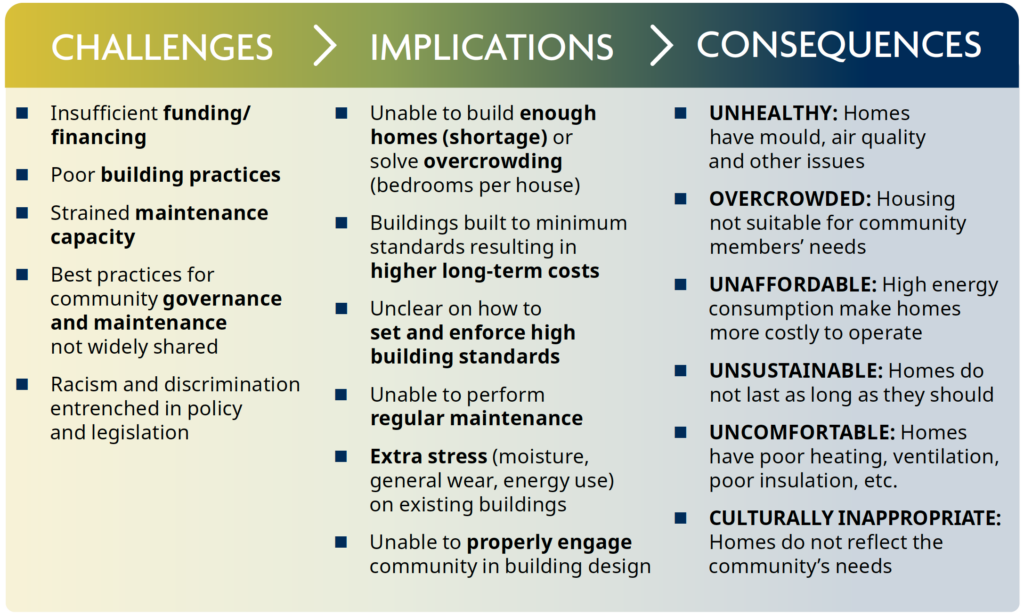

Provincial mining laws and regressive amendments

Recent amendments to the provincial mining law, the Mining Act, ushered in by Bill 71, Building More Mines Act, 2023 (Bill 71), upended already minimal protections in place for Indigenous rights, the environment, and communities. The amendments reduced requirements on mining companies to cover the costs of cleaning up once mining operations have closed, removed the need for detailed closure plans prior to starting operations, and allow mining operators—and not the government—to review the adequacy of technical plans.

There’s a good reason for financial and closure plans to be required in full detail upfront. Ontario is the largest mineral producer in Canada but it’s also the province with a disproportionate share of orphaned and abandoned mines—5,000 of Canada’s 10,000+ are within the province. Bill 71 weakened the existing standard that requires a company to prepare a mine closure plan before it can start building the mine.

As the Friends shared with the Ontario legislature when Bill 71 was proposed, these changes take Ontario back to a time when there was insufficient mine closure planning and financial resourcing, causing hundreds of thousands of tonnes of highly toxic chemicals to remain on the landscape. The impact of these reforms and resulting pollution is most likely to be felt by Indigenous communities. As the UN Rapporteur on toxics observed, following a tour of Canada in 2020, “Indigenous people in particular find themselves on the wrong side of a toxic divide.” It was within this context that the Friends requested Bill 71 be withdrawn in its entirety.

This provincial context is critical to understand in light of the mining interest in the Ring of Fire region. Toronto-based Juno Corp has become the single largest claim-holder in the region, controlling over 17,000 mining claims (covering ~333,000 hectares)—more than half of all claims in the Ring of Fire. The second-largest holder is Ring of Fire Metals (Wyloo’s subsidiary), with over 10,600 claims.

Unfortunately, Ontario has purposely removed the opportunities to ensure that Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, and control their lands and territories as required by Article 26(2) of UNDRIP; that free, prior, and informed consent for any project affecting Indigenous lands and resources be obtained, per Article 32(2) of UNDRIP. Ontario’s laws remain stagnant on the recognition of and respect for Indigenous Natural Law.

Case study analysis

Land-based mobilization, ceremony, and advocacy

In the face of top-down decisions and near exclusion from decisions being made impacting Indigenous rights and land, the grassroots response to the proposed Ring of Fire development is growing. Its growth is also deeply rooted in the land itself.

A powerful example of this occurred in fall 2023, when the Friends of the Attawapiskat River organized a multi-week canoe expedition down the Attawapiskat River, bringing together youth and Elders from across the region to assert their presence and responsibility on the land. Youth from communities including Attawapiskat and Neskantaga navigated ancestral waterways for 240 miles. Along the journey they held ceremonies at key sites. This journey was far more than a canoe trip—it was a form of ceremonial stewardship.

[Click to see in English] ‘ᐆ ᐊᐳᐎ ᔕᓇᐙᑕᔥᑣᐤ ᓂᑕᔭᒨᓇᓂᔫ ᑭᔦᐦ ᑖᓐ ᐁᐦᐃᔥ ᒋᔅᒡᔩᑖᑰᐦᐆᔮᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐄᔨᔫ ᑖᐸᐌᐦᑕᒨᓂᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐐ ᑲᓇᐌᔩᑕᒫᒡ ᒉ ᒫᒨ ᐊᐸᑕᔥᑖᔮᒡ ᐊᔅᒌ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉ ᒦᔫ ᐐᒉᐆᑑᔮᒡ᙮’ -ᐯᔭᒃ ᐊᓐ ᑳ ᐊᐹᒡ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓐᐦ ᒌᐃᔥ ᐐᑕᒻ

“This paddle is our statement, in recognition of who we are, as Treaty peoples, in honouring promises to be Kind, to Share, to be Honest – that is our Strength.”

— member of the Friends

By travelling the river and caring for the water through ceremony, participants reinforced their spiritual connection to the territory and drew attention to what is at stake if the river were to be polluted or harmed by development. Such land-based actions embody the principle that climate action is not just about policy but also about relationship to place, demonstrating an Indigenous approach of environmental guardianship that blends activism with cultural practice.

Insights and challenges from the grassroots mobilization

The Indigenous-led climate action around the proposed Ring of Fire development offers several key insights.

First, it demonstrates that Indigenous laws and knowledge are central to viable climate solutions. Whether through the revival of Treaties as living agreements or the formation of coalitions like Friends of the Attawapiskat River that operate according to Indigenous values, these efforts show alternative models of stewardship. Because of governments’ reticence to implement UNDRIP into provincial law and industry’s lack of respect that consent must be provided before any extractive developments occur on Indigenous lands, getting to a time and place when there is respect for Indigenous Natural Law remains a critical goal of the Friends’ work and advocacy.

Second, the Indigenous grassroots movement underscores the importance of ceremony and land-based healing in activism. By conducting ceremonies at places harmed by extraction, Indigenous land protectors both recognize the trauma to the land and reaffirm their duty to care for those places. This process can strengthen community resolve and present a moral narrative that aligns with Indigenous worldviews and law. It reminds everyone that beyond the charts of ore deposits and carbon emissions, there are sacred relationships and spiritual bonds that cannot be quantified. While impact assessment, as a process, is one mechanism that could allow for considerations of social and cultural values (and also allows space to substitute Crown IA processes for Indigenous-led processes), because of its broad lack of application to most mining projects, this remains an underdeveloped forum for Indigenous-led decision-making.

Due to years of feeling misled or excluded, the Friends are among the Indigenous voices pointing out a deep erosion of trust in government and industry actors. The grassroots people—the people of Treaty 9—are owed a fiduciary duty. Instead, Ontario is relying on divide-and-conquer tactics to push forward a project absent the free, prior, and informed consent of all communities.

[Click to see in English] ‘ᐊᓂᒌ ᒥᔑᑲᔔᐊᓂᒡ ᐊᔭᐆᒡ ᐁᐄᔥ ᐯᐦᑖᑲᓯᑣᐤ᙮ ᓇᒪᐐ ᐆᔦᔑᓐ ᐐᒌᓀ ᓀᔥᑕ ᐋᑳ ᐐᒌᓀ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐄᔨᔫ ᐄᑕᐎᓂᒡ᙮ ᐐᑖᑲᓐ ᐊᓐᒌ ᑳ ᓂᑑᐦᐆᑣᐤ ᐊᒃᔦᐦ ᑳ ᓅᑕᒣᓭᑣᐤ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐊᔅᒌᒡ᙮’ -ᐯᔭᒃ ᐊᓐ ᑳ ᐊᐹᒡ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓐᐦ ᒌᐃᔥ ᐐᑕᒻ

“The grassroots have a voice. It doesn’t matter if you live on or off reserve. It means everybody that hunted, trapped, fished on the land.”

– member of the Friends

Policy recommendations

Recommendation 1: Recognize and support Indigenous declarations of lands protection

A powerful long-term solution to safeguard the Hudson—James Bay Lowlands is to establish Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) led by Indigenous peoples. While the meaning of an IPCA will vary among communities, they often share three core principles: (1) they are Indigenous-led; (2) they represent a long-term commitment to conservation; and (3) they elevate Indigenous rights and responsibilities.

The creation of IPCAs creates the space for Indigenous communities to lead in protecting lands and waters. An IPCA would formally designate large swaths of the peatlands and watersheds as protected from industrial development, under governance models that centre Indigenous law and stewardship. Such IPCAs would recognize—at their core—the need to uphold Treaty rights.

[Click to see in English] ‘ᐐ ᔮᔫᑕᐆᒡ ᐊᔅᒌᔫ ᐁᐆᒃ ᐙ ᐄᑑᑕᒀᐤ᙮ ᐋᐹᐦᑑ ᒉᐄᒥᔅ ᐯᐄ ᐁᐦᐄᔥᐸᔖᒡ ᒋᑲᐄᔥ ᐲᑲᐸᑕᒨᒡ᙮ ᒋᒃ ᓅᑲᓐ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐆᒡ ᒌᔑᑯᕝᐦ ᑲᔩᔥ ᒪᔑᓈᔥᑌᐦᐾᒡ᙮ ᐁᐦᑲ ᒫᒃ ᐄᑑᑕᒥᒣᐦ ᐊᓐ ᑲᔩᔥ ᐐ ᐄᑐᑕᒥᓐ ᑭᔭᐦ ᔖᔥ ᐆᓈᑕᔥᑕᔩᓐ᙮ ᔖᐧᐦ ᑕᔅᑖᑯᐗᐦᐋᐤ ᐆᑳᐐᒫᐤ ᐊᔅᒌ᙮’ -ᐯᔭᒃ ᐊᓐ ᑳ ᐊᐹᒡ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓐᐦ ᒌᐃᔥ ᐐᑕᒻ

“What they’re going to do is basically rape the land. You’re talking about an area maybe half the size of James Bay that they’re going to tear apart. It’s going to show up in the satellite. And once you do that, you’ve already damaged it. Mother Earth has already been hurt.”

– member of the Friends

In calling for the protection of region where the Ring of Fire is proposed, the Friends have released a declaration stating:

[Click to see in English] ᒌᔭᓅ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐅ ᐁᔨᐅᓯᓇᑳᓱᐐᒃ ᒥᔑᑲᔔᐊᓂᒡ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐆᒡ ᐄᔫᐊᑕᔥᑌᔨᑕᒨᐎᓐ 9 ᑲᔦᐦ ᐋᐌᓂᒡ ᐄᔨᔫ ᑳ ᓇᓃᐴᔥᑕᒧᐙᑣᐤ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᓐᑐᐌᐄᑖᑯᒡ ᒉᒌ ᐊᓂᔥᑲᒨᔮᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐸᑕᔅᒋᓂᒫᒡ ᐁᔥᒃ ᐋᑳ ᐆᔥᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᐊᑕᐦᑑ ᒉᒌ ᐊᑎᔅᒀᑏᐸᐧᐎᒡ ᒉᒀᓐ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᒋᑕᔅᒌᓅᒡ᙮

ᐆᔥᑖᐦ ᐆ ᐊᔑᒪᐙᑎᔒᐌᐎᓐ ᐁ ᒦᔫ ᑲᓇᐗᑉᑕᑲᓅᒀᐤ ᐊᒌᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᓂᐲᐦ ᐁᐦ ᐄᔅᐸᓂᑳᒡ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐆᕝᐦ ᐊᔥᒌᐃ ᐁᐦ ᓇᓈᑲᑕᔥᑖᑲᓅᒀᐤ ᐊᑕᐯᔨᒋᒉᓲ ᐄᑕᔅᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᓐ ᒋᔨᔥ ᐋᐸᑕᓰᑲᑕᒨᒃ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐄᔥ ᓃᔣᔥᒡ ᐋᐴᓂᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉᒌ ᒌᑲᐙᐸᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᒪᒨ ᐁᐄᔥ ᑲᓇᐗᐸᑕᒃᓅᒡ ᒉ ᒋᐤ ᒦᔫ ᓃᐴᒪᑯᒡ ᐊᒻᑦ ᐄᔨᔫ ᐊᑕᔥᑌᔨᑕᒨᐙᑲᓐ ᒉ ᒦᔫᑲᑑᑕᒫᑐᐐᒃ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉ ᒦᔫᐊᑎᔥᒉᐃᑕᒨᐦᐄᑕᐐᒃ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉ ᒪᒨ ᐋᐸᑕᔥᑕᔨᒃ ᐊᔅᒌ

WE, AS THE GRASSROOTS of TREATY 9, who are Indigenous rights holders and whose consultation and consent is required prior to any development in our territories

MAKE THIS DECLARATION OF PROTECTION FOR THE LANDS AND WATERS under our Natural Laws and as our commitment to the next seven generations, and in recognition of our shared responsibility to uphold Treaty rights to be kind, to be honest, to share the land

This statement, which remains open for public sign-on and endorsement by allies, is akin to an IPCA, recognizing that Canada’s commitment to protect 30 per cent of its lands and waters by 2030 cannot be met without protecting places like the James Bay Lowlands, and doing so in partnership with Indigenous peoples offers a path consistent with reconciliation.

The declaration also advances the global targets for biodiversity protection set out in the recent Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework reached at COP15. Among the targets that promises the furtherance of Indigenous leadership in conservation is Target 22. It is pivotal in providing new starting points for the protection of environmental human rights defenders, requiring conservation decision-making to fully and equitably respect the cultures and rights over lands, territories, resources, and traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples. As the text reads:

TARGET 22

Ensure the full, equitable, inclusive, effective, and gender-responsive representation and participation in decision-making, and access to justice and information related to biodiversity by Indigenous peoples and local communities, respecting their cultures and their rights over lands, territories, resources, and traditional knowledge, as well as by women and girls, children and youth, and persons with disabilities, and ensure the full protection of environmental human rights defenders.

For the federal government to achieve Target 22, IPCAs (like the protection declaration made by the Friends), are a critical way forward. The intrinsic value of IPCAs in safeguarding biodiversity echoes the growing recognition that Indigenous Natural Laws, which teach respect and responsibility to lands, have been more effective at protecting the health of ecosystems and species than the traditional conservation practices established by the governments in Canada.

ᒋᒌ ᐄᑐᑕᒃᓅᒡ 2: ᐁᐦᓇᑐᐌᔨᑕᑯᒡ ᐁᐦ ᐐᑖᑲᒡ ᒥᔐᐁ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐆᑖᒡ ᑲᔦᐦᓄᐦ ᒋᔅᒉᔨᑲᒪᐦᐊᑲᓅᑦ ᒉ ᓇᐦᐁᔨᑕᒃ (FPIC) ᑆᐅᒥᔥ ᐊᑕᐦᑑ ᐗᔨᐦᐆ | Recommendation 2: Require meaningful free, prior, and informed consent before any further approval

As a matter of urgency, the Friends have called for a moratorium on decision-making for the proposed Ring of Fire, urging governments to halt the practice of granting mining claims and mineral exploration permits absent the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) of Indigenous rights holders. FPIC means that Indigenous communities have the freedom to decide (free of coercion), are engaged early (prior to any final decision or ground disturbance), and are fully informed of all implications, with the opportunity to say yes or no on their own terms.

To implement this, the Friends have said that Ontario and Canada should, at minimum, pause the approval of any new mining exploration permits, road construction, or other project advancements until consent is obtained from all affected First Nations. Grassroots voices, not just Band council leadership, need to be heard and heeded; special effort should be made to include Elders, women, and youth, whose perspectives are sometimes bypassed in Crown consultation frameworks.

ᒋᒌ ᐄᑐᑕᒃᓅᒡ 3: ᐁᐦ ᐃᑕᔥᑌᔪᑕᒃᓅᒡ ᐄᔨᔫᒡ ᐆᐐᔗᐎᓂᐅᐗᐅ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᐄᔥᐸᒥᒡ ᐁᐅᒡ ᓇᓈᑲᑎᔥᑕᑲᓄᐐᒡ᙮ | Recommendation 3: Respect Indigenous assertions of sovereignty

As a corollary to the above recommendations, policymakers should seriously consider the call issued by multiple First Nations and environmental groups for a moratorium on development in the Ring of Fire until certain conditions are met. Those conditions, as articulated by the Friends include: (a) robust protection plans in place for the sensitive peatlands and waterways, and (b) the basic needs of local communities (like clean drinking water, housing, and health services) being addressed before any mining “opportunities”.

[Click to see in English] ᒋᑲ ᑲᓄᐌᔨᑌᓅ ᐊᓐ ᑲ ᓂᔅᑯᒥᓇᓅᒡ ᐊᓐᒌᔥ ᑲᔦᐦ ᓇᐐ ᐊᑐᔥᑐᑦᔐᓈᓐ ᐊᔭᒨᐎᓐ ᐁᐦᐐ ᑲᓄᐌᔨᑕᒧᒃ ᐊᓐ ᑲᔨᔥ ᓇᔅᑯᒧᓈᓅᒡ ᒋᔩᔥ ᐐᑕᒨᒡ ᐊᓐᒌ ᐄᔫᒡ ᑲ ᐄᑕᑕᐗᒡ ᐊᓐᑕ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓂᒡ᙮

“We have to keep that harmony today… We’re trying to send a message that we need to keep the harmony in place.”

– member of the Friends

No development should go ahead in an area when fundamental environmental and social safeguards are absent. By instituting a temporary moratorium, governments would create space for the proper assessments, FPIC processes, and conservation planning to occur. The precautionary principle in environmental policy dictates that lack of full scientific certainty (for instance, about the hydrogeology of peatlands or the cumulative climate impact of mines) is not a reason to postpone measures to prevent degradation. In line with this, a pause on Ring of Fire activity would prevent irreversible decisions from being made in haste.

Conclusion

The advocacy of the Friends in protecting Treaty 9 lands and waters in the face of proposed Ring of Fire development is a reminder that Treaties are living promises that must guide present and future actions for ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the river flows, as long as the grass is green and the Anishinaabe are here.’ The Friends’ grassroots efforts show a path forward. Whether a policy maker, industry representative, or member of the public, everyone has a shared responsibility to uphold shared Treaty rights and commitments to be kind, to be honest, and to share.

[Click to see in English] ᐊᓐ ᐐᒉᐙᑲᓂᐦ ᐊᑎᐸᒋᒨᓐ ᐊᐌᐃᔐᑌᐤ ᒉ ᐊᑌᐦᐳᐗᑕᑲᓅᒡ ᐋᒌᔫᓐ: ᒉ ᐐᒋᐦᐊᑲᓅᒡ ᐃᔨᔫ ᐁᐦ ᓈᑭᑌᔨᑖᒃ ᐊᔅᒋᔫ ᑲᔦᐦ ᐊᓐ ᒉ ᐊᑕᒋᔐᔨᑕᒨᐦᐄᐌᑦ ᐊᓂᔫ ᐐᔑᐌᐎᓂᐦ ᐊᔅᒌ ᐆᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉᒌ ᐊᑦᔥᑌᔨᑕᑲᓄᐐᒡ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒉᒌ ᓅᑲᑕᐦᑲᓄᐎᒡ ᐁᐦ ᓇᓈᑲᒋᔥᑕᑲᓄᐐᒡ ᒋᔅᑕᔅᒋᔫᓂᔫ ᑲᔦᐦ ᓃᐲᔫᐦ ᑲᔦᐦ ᒋᔅᑖᐎᓂᔫ ᐄᔥᒌᔗᐆᒡ ᒉ ᒥᔫ ᑲᓇᐙᐸᑕᒀᒡ ᐊᓐᑌᐦ ᓃᔥᑕᒥᒡ᙮

The Friends of the Attawapiskat River story serves as a call to action: Support Indigenous land protectors, advocate for the Natural Laws and that they be respected, and recognize that protecting lands, water, and communities means safeguarding our collective future.

1 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, SC 2021, c 14, s 4(a)

2 See sections 18 – 25 of the regulation commonly known as the ‘Project List,’ Physical Activities Regulations, SOR/2019-285