Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series of Indigenous-led climate research, produced in co-operation with the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources.

The Golden Rule, as it is commonly known today, of treating those around you how you would want to be treated, is a moral principle of philosophy found in many cultures throughout the world. Remote Indigenous communities on the west coast of Canada are no exception. In a recording taken in the early 1990s, late Ahousaht elder Caroline Little shared a story in her language that invokes this same principle. When revealing the lesson in the story, she said “ʔuyaasiłaƛ n̓aas” (uh-yah-sith-akth naws), which means “something happened to the weather.”

In Caroline’s story, the weather was the protagonist, wielding its power and might to enforce the important teaching to treat others with respect. Her story is best told through her language, where the English constraints of isolating environment and land from the community cannot take hold; within her language these important concepts are interconnected. Compared to the ancient roots of Caroline’s language of Nuu-chah-nulth, climate change is a relatively new concept that is now making its way into languages throughout the world. Nuu-chah-nulth does not yet have a direct translation for this concept. However, through language and stories like Caroline’s, we can better understand climate change and our response to it, within the living moral principles and teachings of effective stewardship, so that we might better strive for oneness with the environment around us.

Faced with the ongoing threat of climate change, Indigenous knowledge and stewardship practices are vital to land use planning and natural resource management. Within Canada, Crown government land use planning departments are gradually beginning to implement policy to act in full partnership with Indigenous communities, recognizing the role that Indigenous stewardship over lands and waters has played in sustainable natural resource management and economic development since time immemorial (Alangui et al. 2018). Additionally, Indigenous communities are increasingly recognizing the benefits and potential of conducting both independent and collaborative planning processes. Land use planning in Indigenous territories that adheres to Indigenous governance and law protocols provides a means to support the well-being of communities and ecosystems. Planning can become a tool for sustainable economic development, environmental conservation, and the minimization and adaptation to climate impacts through incorporating Indigenous knowledge and culture into decision making.

For Indigenous knowledge to be implemented appropriately throughout these planning processes, Indigenous communities must either act in a leadership capacity or be full partners if the planning involves provincial, federal, or municipal orders of government.

The use of Indigenous languages, and specifically Indigenous place names, is a significant dimension to stewardship that can be unearthed through Indigenous-led planning.

Indigenous language and knowledge should also play a significant role in climate action efforts. The value of Indigenous knowledge comes from living among and as one with the land and understanding the complex systems and gradual changes taking place over time. In many cases, particularly throughout Indigenous communities in Canada, this knowledge is shared through the language and oral history, and in many cases the true value of the knowledge is often very challenging to translate. For Indigenous communities, language carries the culture, teachings, law, governance, and connection to the territories. Language sits at the heart of stewardship. With most Indigenous languages in Canada at risk of extinction, recognition and preservation of these languages are necessary responses to decipher the knowledge needed to combat climate change (Krupnik et al. 2018).

Amongst British Columbia’s 34 Indigenous languages (First Peoples’ Cultural Council 2018), many have words or phrases similar to hišuukiš cawak (hish-ook-ish tsah-wok), or “everything is one and interconnected,” in the Nuu-chah-nulth (new-chah-noolth) language, from the west coast of Vancouver Island. This important teaching, heard throughout many communities in different regions, references the deep connections that Indigenous communities have with their surrounding lands and biodiversity. It speaks to the inherent need and sense of duty to preserve, respect, and protect one’s relations and one’s community.

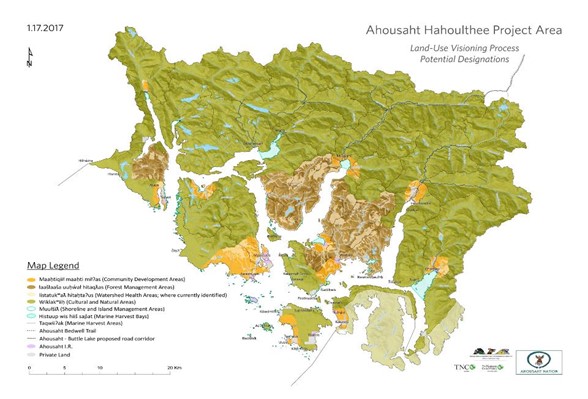

As guided by the language and the teaching of hišuukiš cawak at the core of stewardship, this case study explores the land use visioning community process of the Ahousaht First Nation. Ahousaht’s land use vision demonstrates how integrating Indigenous place names into planning processes can provide critical biological and cultural details to inform policy and management regimes and better understand the impacts of climate change.

Indigenous land use planning in British Columbia

Indigenous communities in British Columbia have been practicing stewardship and sustainable management of natural resources since time immemorial (New Relationship Trust 2019). Stewardship was not historically achieved through contemporary land use planning processes as we see them today, of course. Instead, it was developed through deep connections and respect for the lands and waters and the inherent understanding of the sustainable use of resources. Indigenous land use planning as we see it today in the province is, by contrast, reactive to encroachment and land allocation by colonial systems, and reactive to the use and management of lands and waters by federal, provincial, and non-Indigenous local governments. Tenures, developments, and divisions enacted from these government bodies have compromised Indigenous stewardship practices as guided by law and governance and have put Indigenous communities in a position of response and reaction. Responses can include partnership, settlement, or confrontation, prompting Indigenous communities to engage in official land use planning processes to fight for continued stewardship over their territories using modern planning techniques that are recognized by external governments and stakeholders.

Today, land use planning for Indigenous communities can take many forms. For example, planning can follow a government-to-government approach, such as British Columbia’s modernized land use planning program (Province of British Columbia 2022b) or it can be developed independently within the community. In the case of the Ahousaht First Nation, land use planning has been developed in partnerships with external stakeholders and non-governmental organizations. The Ahousaht land use vision was completed independently from crown government within the community, with technical and financial capacity and support of an external conservation organization (Maaqutusiis Hahoulthee Stewardship Society 2017).

The Ahousaht First Nation on the west coast of Vancouver Island, the focus of this case study, named their process a land use vision to clearly demonstrate that it is a working document that adheres to Ahousaht law and governance protocols, and is to be revised and revisited as needed.

This coastal community places particular importance on allowing land use adjustments and changes to best serve the community and the territory most effectively for future generations.

Climate change and land use planning

British Columbia is already seeing the devastating impacts from climate change, including mass flooding, harrowing wildfires, and drastic weather changes that set new temperature or precipitation records each year. Rural and Indigenous communities face particularly high risks from these impacts. Many rural and Indigenous communities in British Columbia have experienced mass destruction and displacement, and the threat of further damages only continues to increase. These communities are particularly vulnerable due to their rural and coastal geographies, socioeconomics, and reduced access to technical assistance. Many communities also lack the capacity to develop and implement robust mitigation, adaptation, and clean growth strategies (Whitney and Ban 2019). Similar to many small island nations around the world that are on the frontline of the climate emergency (Climate Refugees 2022), many coastal communities in B.C. have become vocal advocates for action at the global level to prevent further devastation. Advocates believe that without the implementation of immediate and substantial climate action, we will begin to experience an outflux of people fleeing their territories due to climate related changes or hazards (Donatuto et al. 2014), rendering homelands inhabitable.

Rising ocean levels, flooding of rivers, and other landscape-level changes are not the only issue: the problem is paired with impacts to food security as a result of changes to food systems from extreme weather events and rising atmospheric air and ocean temperatures (Marushka et al. 2019). These changes cause the ocean to become less productive, the numbers of plants and animals used for sustenance harvesting and cultural practices to dwindle, and fresh water to become scarce and contaminated. Local economies suffer, with loss of revenues from commercial harvesting and downturns in tourism from the lack of proper infrastructure and the degradation of the natural landscape. These effects are gradual but substantial, widespread, and cumulative, and must be met with natural resource management and land use planning from an Indigenous perspective that has been proven sustainable over thousands of years.

Ahousaht First Nation’s Land Use Vision

This case study examines the Ahousaht Land Use Vision developed by the First Nation of Ahousaht, which is located on the west coast of Vancouver Island, approximately 40 minutes north by boat from the popular tourist town of Tofino. The Ahousaht territories cover over 170,000 hectares, span from Meares Island near Tofino Harbour to Hisnit near Hesquiaht Harbour, and encompass large portions of Vancouver Island including parts of what is known as Strathcona Park. The territories include temperate rainforests, countless islands, many shorelines, and mountain ranges with extensive biodiversity and habitat. They are known throughout the world for their beauty and bounty and as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO 2018).

Ahousaht First Nation, as it is known today, was originally made up of six separate nations that were amalgamated through war. What is now the Ahousaht main village of Maaqtusiis (mock-too-cease) was formerly the village of the Uutsuutsaht (oots-oots-sawt) people. Ahousaht has a governance structure comprised of three houses, each led by a hereditary chief, hawił (hah-with), and each with different roles and responsibilities within the community. In the 1950s, a chief-and-council governance structure was implemented in Ahousaht through the Indian Act by the Federal government. This form of governance was intended to replace the hereditary structure, using an electoral system to seat new leadership, though in Ahousaht the inaugural chief and council were appointed by the hereditary chiefs rather than elected.

Today, both hereditary and elected governance structures persist, though the hereditary chiefs no longer appoint chief and council. Elections are now held by the community, and the chief and council under this colonial governance system have been empowered by the Crown government under the Indian Act to act on behalf of the community. This outside approval and influence represent an example of how colonial systems have been undermining cultural governance since first contact and, in many cases, have impeded Indigenous communities from maintaining stewardship practices over their lands and waters.

In an effort to re-establish its stewardship and enact Ahousaht law and governance over natural resource management, the Ahousaht hawiiḥ (hah-way-ah) established the Maaqutusiis Hahouthlee Stewardship Society in 2012.[1] The Society engages in all matters of resource management and economic development for the entirety of the Ahousaht territories under the four guiding principles of iisʔaḱstaƛ (ee-sock-stockth), respecting one another, haaḥuupstaƛ (ha-hope-stockth), teaching one another, yaʔakstaƛ (ya-uck-stockth), caring for one another, and huupiił’aƛ (who-peeth-ahkth), helping one another.

Under the Stewardship Society in 2016, the Ahousaht hawiiḥ opened the land use visioning process with intensive community sessions with Ahousaht people living both within the territories as well as in select urban centers where many Ahousaht people reside. Community members were asked to provide input into maps to outline their ideas on future conservation and developments within the territories and share ideas on which areas hold cultural significance and should be preserved. This process yielded seven distinct land use designations that defined the allowable and prohibited activities within each. Designations that held potential for more intensive development include the Forest Management Areas and the Communities Development Areas, accounting for just under 18 per cent of the total territories. The designations slated for measures more aligned with conservation encompassed the remaining 82 per cent of the Ahousaht territories. These designations include Watershed Health Areas, Cultural and Natural Areas, Shoreline and Island Management Areas, and Marine Harvest Bays.

Through the planning process and the appointment of specific land use designations, the importance of including Ahousaht place names was repeatedly highlighted. Acknowledging and incorporating these place names underscores how place names can reveal and apply a deep knowledge of the changing landscape, demonstrating the importance of ensuring that Indigenous place names are reflected in matters of the lands and waters.

Ahousaht’s place names reflect a different relationship with the land and waters than the modern colonial place names that are used today. Ahousaht place names do not encompass large areas but rather smaller defined areas. They are sometimes circumstantial and reference the experience of one individual or a one-time occurrence, but some also allude to the ecosystem services, biodiversity, and cultural importance of sites, as further analysis of the origin of the name can reveal.

The impetus to incorporate the knowledge held within place names into the Ahousaht Land Use Vision, as well as the actual place names themselves, came mainly from the participating community members and elders who engaged in the planning sessions. In conducting this research, the Stewardship Society also relied on a research project published in the 1990s by Canadian forestry company MacMillan Bloedel, which has proven to be a very useful resource that includes interviews with elders documenting over 900 Ahousaht and Tlaoquiaht place names (Bouchard and Kennedy 1990). Within each place name description, Ahousaht elders shared their insights on each name as well as their experiences of specific biological changes at the places that were the result of colonization or a shifting climate. Examples of such changes include reference to abandoned spawning areas where fish were once abundant, or where seasonal homes were once built and now no sign of them remains. Historical knowledge and indicators such as these can provide vital information allowing for critical data input into the land use planning process, such as helping to determine locations for focused salmon restoration efforts, ideal areas for residential development or expansion, or areas in need of enhanced conservation measures.

Indigenous knowledge for climate action in land use planning

Historically, Ahousaht villages were located near areas of sustenance gathering, and many place names indicate this alignment within the Community Development Area designation. T̓iikwuwis (teak-woo-wis) describes a root-digging beach, ʕisaqnit (ice-awk-nit) a place of wild onions, and mukʷnit (moo-kwin-it) a place where the deer feed on ferns. The names provide guidance to the unique characteristics that made each of these sites habitable for the Ahousaht people prior to colonial contact, knowledge that is critical to the well-being of a community that is heavily dependent on sustainable harvesting.

The Ahousaht Land Use Vision that emerged from this research establishes designated Community Development Areas that have been identified as areas for potential future residential expansion outside of Maaqtusiis. The population of Ahousaht is large and continues to grow, requiring infrastructure growth within Maaqtusiis and into other areas of the territories. The Ahousaht Hawiiḥ want to ensure that there are space and opportunities available for Ahousaht people wanting to live and work in the territories. They hope to create this space through stewardship, sustainable development, and diverse economic and career opportunities.

Place names can also inform community planning by identifying landscape features that could impact infrastructure development. ʕaʔukʷnak (eye-ah-u-kwin-awk), for example, which is a community adjacent to Maaqtusiis, has undergone improvements and expansion for residential homes. ʕaʔukʷnak translates to “it has a lake,” and this lake was said to once house a special species of sockeye salmon when the Uutsuutsaht inhabited this area. This lake used to drain into the bay on the shoreline, though in the early 1900s, when missionaries came to Maaqtusiis to build a residential school, they filled in this lake to turn it into a field. As nature took back over, some of the water returned, creating a bog that now houses cranberries that the community harvests.

Ahousaht is particularly vulnerable to rising water levels, rising ambient temperatures, and rising ocean temperatures. The Ahousaht Land Use Vision has designated areas as Shoreline Management Areas, which encompass large portions of the shoreline throughout the territory. This designation allows for the maintenance of conservation zones for food harvest, cultural access, and transportation, even when those areas are adjacent to other designations within the Land Use Vision that allow for more intensive development opportunities.

These shoreline areas include areas of great cultural, historical, economic, and social importance to the Ahousaht community. For example, Numaḥt̓aʔa (new-mah-ta-ah), meaning “forbidden creek,” references a historical site where significant events occurred, as detailed through oral history. The importance of this site to the Ahousaht community led to it being granted a specific Shoreline Management Area designation, to ensure that the history and teachings from this site are respected and preserved.

Many place names also reference the food that is or was available for sustainable harvest by the Ahousaht people. Huʔuł (who-oolth) is such an example, translating to “where the cormorants slept,” indicating that this is an island frequented when hunting cormorants. Nearby is Qʷinqiit (kwin-keet), which describes the area as a seagull resting place and where seagull eggs are gathered. These precious shoreline areas may be the first impacted by rising tides and warmer oceans, compromising nesting grounds and food sources of critical beings in the holistic community ecosystem. The region’s great biodiversity is not only a source of sustenance for the people of Ahousaht; it is an essential part of the cultural teachings of hišuukiš cawak, underscoring the responsibility of those who live in relationship with this territory to protect it.

Integrating place names into the Ahousaht Land Use Vision has not only helped the people of Ahousaht to see and recognize the actions that must be taken to better prepare for and adapt to a changing climate. It has also helped non-governmental planning partners, Crown governments, and stakeholders to see as well. Within the Ahousaht territories, place names serve as a reminder of the bounty that the delicate shorelines, rich forests, and vast marine areas provide the Ahousaht people sustenance, culture, wayfaring, biodiversity, and ecosystem services.

The bay of ƛakišus (clock-ish-us), protected under a Cultural and Natural Area designation, is one example of the bounty that these names reflect. It describes the use of the area by migratory grey whales for rubbing the beach to rid themselves of barnacles and parasites. This rubbing is a critical ecosystem service being provided to the whales, iiḥtuup (ee-hah-toop), further highlighting the intent for protection and preservation under a conservation land use designation at this location. Maqy̓aaqw̓aqƛił (mawk-yawk-walk-klith), a cave in Millar Channel on the east side of Flores Island which has also been granted a Cultural and Natural Area designation, represents a culturally important site for the Ahousaht. Translated as “corpses in a cave,” Maqy̓aaqw̓aqƛił was historically used for burial and is only accessible at specific tidal levels.

Place names also serve as markers for history and teachings of the area, such as at the shores of Katkuwiis (kut-koo-ees), located along the well-known ecotourism corridor the Wildside Trail. The trail sees hundreds of visitors a year passing through the village and the beaches, bringing with them economic opportunities for community members. This section of the trail, currently known as White Sands Beach, is a popular section for camping, though this is also a key location in a gruesome 14-year battle that took place in the early 1800s between the Ahousaht and Uutsuutsaht (Sam 1997). This was the battle that ended with Ahousaht taking over the Uutsuutsaht territory and amalgamating the nations. As the risk of rising ocean levels looms, this area, which defines current governance within the territories through the amalgamation and acts as a historical touchstone, a significant tourism destination, and a catalyst for sustainable economic opportunity, may soon be lost to the tides.

Place names can indicate the possibilities of what is to come in the future, as well as what has been lost. The place name Cuuxʷnitapi (tsoo-kwin-it-app-eh), translating to “coho jumping”, indicates an area of shoreline in Bedwell Sound at the mouth of the Bedwell River. One of the elders interviewed by Bouchard and Kennedy (1990) shared that he had not seen coho there before, but that it was historically understood that this is where they once ran. Specific historical knowledge about this area has helped to develop salmon restoration projects over the past couple of decades and has initiated further salmon saving efforts.

The Ahousaht Stewardship Guardians, a program under the Maaqutusiis Hahoulthee Stewardship Society tasked with stewarding the territories under the direction of the hawiiḥ, even took drastic measures during the 2021 heatwave by moving juvenile coho out of warm, shallow pools into deeper areas of the Bedwell River where they could better escape the deadly heat (Wood 2021). The Ahousaht Stewardship Guardian Program is implementing the knowledge found within place names for on-the-ground efforts for cultural stewardship, as well as for observation of climate-related changes on the lands and waters.

Many Indigenous communities throughout British Columbia have similar stewardship programming, providing an ongoing presence in their respective territories. Such programming is critical for implementing land use planning within Indigenous territories. It is also on the frontlines of data collection and observation of the impacts of climate change on the landscape.

Conclusion

Retention and revitalization of language and land-based knowledge are necessary for land use planning and natural resource management within Canada and around the world. The Ahousaht Land Use Vision highlights the importance of recognizing Indigenous place names as cultural and land-based knowledge that can help guide natural resource management and climate action from an Indigenous perspective. Investing in stewardship capacity and programming can establish data hubs within Indigenous communities that can cross-reference cultural knowledge such as place names with biological and ecosystem features and changes.

Many Indigenous communities throughout Canada have already begun such initiatives, despite the limited support from Crown governments for these programs. Unfortunately, given the geographical vastness of the country and the complexity of data storage and collection, stewardship programming is not yet given the same weight and importance as academic or research institutions. The collection and analysis of cultural and environmental data are crucial to the ecological restoration and good governance of communities throughout Canada—Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike—and each community should be empowered and supported in undertaking this important work, which is vital to long-term health and well-being.

Additional funding and support from provincial and federal governments should also be provided for Indigenous communities to undertake the research and recording needed to document place names and implement unofficial and official place name changes within their territories. Formalizing these changes and having the names adopted and made into law would provide greater opportunity for education and cultural resilience. Efforts to integrate Indigenous place names can be supported by the departments currently responsible for unofficial and official name changes at both the provincial and federal levels with Natural Resources Canada (NRCAN 2022) and the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations, and Rural Development (Province of British Columbia 2022a). Simplifying and streamlining the process for Indigenous communities to restore their place names through official and unofficial name changes would promote greater awareness around climate risks and adaptation solutions, while furthering language revitalization, reconciliation, and Indigenous knowledge data collection.

Updating policy regarding the environmental, social, economic, and cultural impacts of land-based decision making at the provincial and national levels would provide Indigenous communities with the opportunity to apply the critical ecological and cultural information that place names and Indigenous knowledge contain. Integrating Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous perspectives at the initiation of land use planning processes is critical. Integration can help establish cultural and ecological Indigenous knowledge data as the baseline and can guide decision making towards the stewardship practices that Indigenous communities have been thoughtfully practicing on the lands and waters for many generations.

Though the resurgence and legitimization of Indigenous place names alone cannot resolve climate change, place names can serve as a tool for local peoples and visitors alike to observe and understand the impacts of climate change on a specific location, drawing on the experience of generations of people upholding the laws of hišuukiš cawak and living as one with the environment around them.

[1] Hawiiḥ is the plural form of hawił, hereditary chief.

References

Alangui, Wilfredo V., Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Kimaren Riamit, Dennis Mairena, Edda Moreno, Waldo Muller, Frans Lakon, Paulus Unjing, Vitalis Andi, and Elias Nguik. 2018. “Indigenous Forest Management as a Means for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation”. In Douglas Nakashima, Igor Krupnik, and Jennifer T. Rubis (Eds.), Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation (pp. 93-105). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781316481066.008

Bouchard, Randy, and Dorothy Kennedy. 1990. “Clayoquot Sound Indian Land Use.” Report prepared for MacMillan Bloedel Ltd, Fletcher Challenge Canada, and the British Columbia Ministry of Forests. Victoria, BC.

Climate Refugees. 2022. “Why.” https://www.climate-refugees.org/why

First Peoples’ Cultural Council. 2018. “Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages”. Third Edition. https://fpcc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FPCC-LanguageReport-180716-WEB.pdf

Donatuto, Jamie, Eric E. Grossman, John Konovsky, Sarah Grossman, and Larry W. Campbell. 2014. “Indigenous Community Health and Climate Change: Integrating Biophysical and Social Science Indicators.” Coastal Management, 42:4, 355-373, DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2014.923140

Krupnik, Igor, Jennifer T. Rubis, Douglas Nakasima. 2018. “Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation: Epilogue.” In Douglas Nakashima, Igor Krupnik, and Jennifer T. Rubis (Eds.), Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation (pp. 280-290). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781316481066.021

Maaqtusiis Hahoulthee Stewardship Society. 2016. “Ahousaht Land Use Vision: Press Release.” https://mhssahousaht.ca/news/press-release-ahousaht-land-use-vision

Marushka, Lesya, Tiff-Annie Kenny, Malek Batal, William K.L. Cheung, Karen Fediuk, Christopher Golden, Anne K. Salomon, Tonia Sadik, Lauren V. Weatherdon, and Hing Man Chan. 2019. “Potential impacts of climate-related decline of seafood harvest on nutritional status of coastal First Nations in British Columbia, Canada.” PLOS ONE 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211473

Nakayama, Toshihide. 2003. “Caroline Little’s Nuu-chah-nulth (Ahousaht) Texts with Grammatical Analysis: Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim.” Nakanishi Printing Co., Ltd. Kyoto, Japan.

Natural Resources Canada. 2022. “Geographical names in Canada.” https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/maps-tools-and-publications/maps/geographical-names-canada/10786

New Relationship Trust. 2019. “An Updated Effective Practices Guide: Land Use Planning by First Nations in British Columbia.” https://www.newrelationshiptrust.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Web-version-FINAL-Kehm_Bridge_Robertson-Updated-NRT-Effective-Practices-Guide-for-Land-Use-Planning-by-First-Nations-in-BC.pdf

Province of British Columbia. 2022a. “Geographical Names.” https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/celebrating-british-columbia/historic-places/geographical-names

Province of British Columbia. 2022b. “Modernizing Land Use Planning.” https://landuseplanning.gov.bc.ca/modernizing

Sam, Sidney. 1997. “Ahousaht Wild Side Heritage Trail Guidebook.” Western Canada Wilderness Committee. Vancouver, B.C.

UNESCO. 2021. “Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve, Canada.” Available from: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/eu-na/clayoquot-sound

Whitney, Charlotte K., and Natalie C. Ban. 2019. “Barriers and opportunities for social-ecological adaptation to climate change in coastal British Columbia.” Ocean & Coastal Management. Pp. 179-1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964569119300390 Wood, Stephanie. 2021. “A lot of salmon died: Ahousaht Guardians look to watershed restoration amid B.C.’s dangerously dry summer.” The Narwhal. September 19. https://thenarwhal.ca/bc-drought-ahousaht-salmon/