Introduction

How did the 2021 extreme heat emergency affect Indigenous peoples in British Columbia? Mainstream colonial academic and policy discourse in Canada often presents a disadvantaged and vulnerable perspective of Indigenous Peoples’ experience. For example, several factors described in the literature present a compounding risk for Indigenous Peoples when it comes to extreme heat:

- Housing standards and overcrowding within homes is a central safety factor when it comes to extreme heat: according to the 2021 federal census, one in six Indigenous people lived in a home in need of major repairs (almost three times higher than for non-Indigenous), and more than 17 per cent of Indigenous people lived in crowded housing (Statistics Canada 2021).

- Indigenous Peoples in Canada are disproportionately affected by the negative impacts of climate change, emergencies, and disasters (e.g., people living on First Nations reserves in Canada are 18 times more likely to be evacuated due to disasters) (Government of Canada 2019).

- Indigenous Peoples are also at significantly higher risk of developing chronic disease than non-Indigenous people (Hahmann and Kumar 2022). Certain medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, lung disease, and diabetes affect the body’s thermoregulation and increase susceptibility to extreme heat (BCCS 2022).

Despite these risk factors, the BC Coroners Service investigations into the B.C. heat wave that occurred in June 2021, found that a “disproportionately low number of Indigenous People died during the extreme heat event.” The report suggests that this may have been because of under reporting due to data collection processes and makes a recommendation for consultation with Indigenous Peoples “to ensure their voices are heard and their needs around heat planning understood” (BCCS 2022). This case study aims to address this gap through meaningful collaboration with Indigenous Peoples.

Methodology

Led by Preparing Our Home, an Indigenous-led network for disaster risk and resilience, this project documents the 2021 heat wave experiences and the subsequent cumulative impact extreme heat is having in five B.C. First Nations. Four sharing circles were conducted, supplemented with five in-depth interviews with community resilience leaders. Participants decided whether to be identified by their name or nation only. The questions were co-developed to ensure that participants’ priorities were reflected. This relational approach empowered nation-to-nation learning and a focus on solutions.

We focused on the experiences with heat in five on-reserve First Nation communities, their lessons learned (in relation to climate change), and, drawing on those lessons, made policy recommendations to create resilience to future extreme heat events:

- Urban: The Tsleil-Waututh Nation, People of the Inlet, are Coast Salish Peoples whose territory includes the Burrard Inlet and the waters draining into it and North Vancouver, where the community has a current population of 600+ people.

- Rurally located Nations in the Interior:

- Originally known as T’eqt”aqtn (the crossing place), Kanaka Bar Indian Band is one of 15 Indigenous communities that make up the Nlaka’pamux Nation. For more than 7,000 years, Kanaka’s traditional territory has sustained its people and today the community is home to between 70-140 residents (Kanaka Bar Indian Band 2022).

- The Líl̓wat Nation’s Territory includes 791,131 hectares of land that occupies a transition zone from temperate coastal environment to the drier interior of B.C. The majority of Líľwat7úl citizens live near Mount Currie which is home to the majority of the 2,200+ members (Líl̓wat Nation 2022).

- The Adams Lake Indian Band belongs to the Secwépemc Nation and is a member of the Shuswap Nation Tribal Council. Adams Lake was once a gathering place for neighbours to meet, socialize, and gather roots and berries and has a present-day population of over 830 members (Adams Lake Indian Band 2022).

- Remote: The Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk Nation) are the main descendants of Haíɫzaqvḷa-speaking people and identify as being from one or more of five tribal groups: W̓úyalitx̌v, Q̓vúqvay̓áitx̌v, W̓u̓íƛ̓itx̌v, Y̓ísdáitx̌v, X̌íx̌ís. With a current population of 2,414 and growing, the Haíɫzaqv people hold strong connections between the community, the environment, and the economy (Heiltsuk Nation 2022).

Context

The land and waters colonially named as B.C. are home to 290,210 Indigenous people and 200 distinct First Nations, representing 16 per cent of Canada’s Indigenous population (First Nation, Inuit, and Métis) and around six per cent of the B.C. population (Statistics Canada 2021). To understand the experiences of extreme climate events such as the 2021 extreme heat emergency in First Nations communities in B.C., it is important to understand the colonial context in which these extreme events take place.

Dispossessing home, land, waters, and way of life

Traditionally, the formation of houses and communities were determined by the land, waters, and relationships with land-sustaining systems. Houses were designed for the local climate, local materials, and the function of the house (e.g., fishermen and women, hunters, trappers, traders, wool workers, wood carvers) (Olsen 2016).

Traditional homes for the Líľwat7úl, Secwépemc, and Nlaka’pamux: Organized in extended family groupings, the Líľwat7úl wintered in villages consisting of clustered c7ístkens, semi-subterranean “pit houses”. In temperate months, life was lived outside, fishing, hunting, and gathering as people travelled a traditional territory of almost 800,000 hectares, from coastal inlets to deep in the rainforest (Gabriel et al. 2017).

Similarly, the Secwépemc c7ístkten (winter home) could accommodate 15 to 30 people or four to five families (Favrholdt 2022). Located close to food sources and a place with loose soil, several c7ístkten would form a community. On the move in the summer for hunting, gathering, and fishing, the Secwépemc generally used c7ístkten from December to March, depending on the severity of the winter. Reused and rebuilt as necessary, these dwellings were used by the Secwépemc and other Interior peoples into the late 19th century.

Among Nlaka’pamux, pit houses were used year-round and provided relief from the heat in the summer. The homes were carefully placed away from water to ensure dry conditions.

Through the Indian Act of 1876, the federal government displaced Indigenous Peoples to sub-standard, small parcels of land and took over jurisdiction for on-reserve housing. The Interior reserves were small, some bands had no reserve land, and one community was given a field of boulders (Harris 2002). No attempt had been made to protect Indigenous fisheries or water for irrigation. In many areas, settlers had taken all available water, leaving most reserves unable to sustain themselves (Harris 2002). This led to dispossession of land, waters, and the way of life that reflected community values.

By the 1940s, government involvement in housing assistance became more widespread with Indian agents arranging the purchase, delivery, and payment of building materials. In this era, reserve residents and band leadership were denied control over financial decisions and housing decisions (e.g., where to live, what type of house to live in, how much to spend on housing). As a result, housing knowledge that the mainstream society took for granted was not available on reserves (Olsen 2016).

Housing infrastructure is a critical factor for heat vulnerability and health outcomes (Samuelson et al. 2020). While lower quality housing is often seen as a marker of poverty within mainstream society, the housing practices established under the Indian Act created poverty (Olsen 2016). This race-based denial of safe housing as a basic human right continues today and manifests in, for example, overcrowding due to lack of housing suited for intergenerational living. Having provided this important context, we now turn to the 2021 extreme heat experiences.

How hot did it get?

The 2021 extreme heat was unlike anything the communities had seen before. Some areas in B.C. experienced record-breaking temperatures up to 20° C above normal (Table 1).

Table 1: 2021 recorded temperatures from the weather stations located near case study communities.

| Location | Average (June, July) | Record | Date (of all-time max temperature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lytton | 24.1° C, 28.1° C | 49.6° C | June 29, 2021 |

| Adams Lake (Kamloops) | 25.1° C, 28.9° C | 47.3° C | June 29, 2021 |

| Haíɫzaqv (Bella Bella) | 13.5° C, 16.4° C | 35.8° C | June 28, 2021 |

| Tsleil-Waututh Nation (North Vancouver) | 14.4° C, 17.0° C | 40.6° C | June 28, 2021 |

| Mount Currie (Pemberton) | 13.6° C, 16.4° C | 43.2° C | June 28, 2021 |

Data sourced from Environment and Climate Change Canada

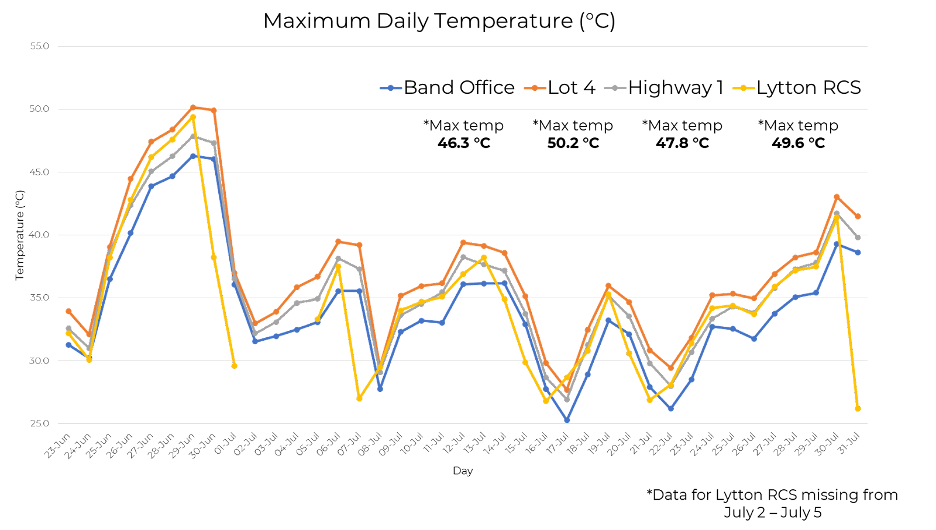

This included Canada’s highest ever recorded temperature—49.6° C on June 29, 2021—in Lytton, located on the Nlaka’pamux Nation territory and the arid, steep, rocky Fraser Canyon. On June 30, Lytton burnt to the ground in 21 minutes. The Kanaka Bar Indian Band’s weather station provided site specific data (Figure 1). It is important to note that some community members in Lytton area shared photos recording 50°+ C in their vehicles and inside their homes on household thermometers before the fire started.

What this experience taught us: community is the solution

“What are our solutions for extreme heat? When we look at this from an Indigenous perspective, it’s community. First and foremost, we have to look after each other.” ~ Patrick Michell, former Chief of Kanaka Bar Indian Band and Lytton resident

Below, we describe community experiences with extreme heat along some of the main themes that were identified in the sharing circles. These include extreme heat impacts on land and waters, and food, as well as experiences in accessing cooling spaces, and climate action.

The urban experience: Tsleil-Waututh Nation

As a coastal urban nation, the consequences of the extreme heat event saw considerable strain on community capacity, the displacement of Elders, dramatic impacts to the land and water, and consequences to food security and sovereignty. The urban narrative, provided by the first-hand experience of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation Health Director, Andrea Aleck, draws on technical, cultural, and community-based wisdom.

Tsleil-Waututh experience of the impacts on the land and water

The 2021 extreme heat emergency had significant impacts on the land and water systems that support and sustain Indigenous ways of life. These impacts resulted in inhospitable conditions for animal and plant life and have cascading consequences for food security and access to traditional medicines.

“Temperature increases have a significant impact on our waters. We are seeing a surge in red tide events, an increase in coastal erosion due to drying of the foreshore and a loss of sea plants that support ocean life and cooler estuaries. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation is working to plant eelgrass as a way to mitigate some of these negative impacts. Not only is this promoting the survival of a native species, it is providing a cultural learning and engagement tool for our community. It is part of our health to be out on our lands and waters and the activity of planting eelgrass nurtures the community perspective of health and offsets the negative changes to our environment.” ~ Andrea Aleck, Tsleil-Waututh Health Director

Tsleil-Waututh experience of the impacts on food security and sovereignty

The consequences of extreme heat on Indigenous food systems and sovereignty were addressed in great detail by Andrea. However, she also highlighted innovative, strength-based, and adaptive solutions being undertaken by the Tsleil-Waututh Nation.

“Food security and sovereignty is a critical area of work for the Health Department and due to the impacts of extreme weather—including the heat emergency in 2021—we are having to think and plan critically around this. We have developed a five-year strategic plan around food sovereignty and community gardening, this includes investments into a hydroponic building where we can grow a veggie from seed to table in a very short period of time.” ~ Andrea Aleck, Tsleil-Waututh Health Director

Tsleil-Waututh response to heat and access to cooling

As a coastal community located at the base of the North Shore mountains, the forest canopy and bodies of water have traditionally offered an escape from extreme heat. The 2021 response required an enhanced level of protective solutions specific to the care of Elders and vulnerable members of the community.

For the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, community health played a critical role in the response to extreme heat. As an immediate protective measure, an analysis of the Elders was done within the community—this assessment considered pre-existing health conditions, their living environment, and identified how Elders could mitigate the risk of heat in their own homes. To ensure that there was continuity to the care, Home and Community Care practitioners were providing enhanced wellness checks, however their findings uncovered the following:

“Even though we had provided fans and some Elders had access to air-conditioning units, we found that they were going unused as Elders could not bear the costs associated with operating the units. This required us to take additional measures and move Elders out of the community and into hotels in our neighbouring non-Indigenous communities. But there is hesitancy on the Elders’ part to leave their homes and leave the community. As a health team and a community, we know that when possible, it is important to stay in the community, that home is a safe place and family is always close by. But in this instance, we knew that we needed to have Elders living in temporary cooler spaces, so to assure safety the Elders were able to bring their companion or care-giver and we found that with additional supports, about 80 per cent of our Elders did decide to go.” ~ Andrea Aleck, Tsleil-Waututh Health Director.

The rural experience: Kanaka Bar Indian Band, Adams Lake Indian Band, and Lil’wat Nation

Over the past five years, communities in B.C.’s Interior have faced compounding hazards of increasing frequency and intensity—from the Elephant Hill wildfire that devastated Ashcroft Indian Band in 2017 to the 2021 fire that burnt down Lytton. Yet, 2021 was a complete departure from previous experiences with extreme heat.

“It’s almost like the air had a crackle in it. It was so strange, but you could smell the trees. You could feel the energy of the trees like when you put a branch of pine on a hot stove. That’s how the whole air smelt, and you couldn’t get away from it nowhere, no matter where you were.” ~ Sheri Lysons, former Licensed Practical Nurse who was the Fire Chief at the time, Adams Lake Indian Band

The duration of the 2021 heat emergency was a particular concern, as Patrick Michell, former Chief of Kanaka Bar Indian Band and Lytton resident shared: “One of the things that changed is extreme heat is occurring in greater frequency, duration, and intensity—emphasis on duration. Lytton in the past had recorded 44.4° C for one day and then in 2021, temperatures closer to 50° C occurred for days; what happens if we stay in excess of 50° C for longer periods? This heat has impacts on land and waters, not only the people.”

The rural experience of impacts on land, waters, and food

“How do we as Indigenous people deal with and prepare for the fact that our homeland is dying? I was prepared physically for the physiological effects on me. I was even prepared mentally, but what I wasn’t necessarily prepared for was the impacts on the ecosystems. That’s different. We’re going to transition from coastal to desert.” ~ Patrick Michell, Kanaka Bar Indian Band, Lytton resident

Sharing circle participants discussed how these extreme events are warnings of a fundamental eco-system disbalance. These warnings are carried by the animals, insects, trees, and the land. For example, the heat brought about swarms of insects by speeding up the reproductive cycles of houseflies, and led to a rapid rise of mosquitoes; wasps also became more aggressive. There is an acute need to listen to these warnings.

“I think what people need to start doing is looking more toward what the land is telling us rather than what science is telling us, because the land has gone and done this for thousands and thousands of years, and it knows the cycles and we need to pay attention to that. Look at what the animals, what the buds are telling you, what the waters are telling you, because they have the answers. We just need to listen.” ~ Sheri Lysons, Adam Lake Indian Band

Extreme heat was accompanied by drought. Combined, these events disrupted the cycles of seeds and plants which in turn displaced animals and began to displace trees. To adapt, the Kanaka Bar Indian Band is setting aside water in reservoirs, so that during the heat and drought there’s still water for the ecosystems, for drinking, for fire protection, and for irrigation.

The heat, insects, and the drought severely disrupted food harvesting and preservation initiatives. Berries and fruit shrivelled on bushes and trees. Bears went hungry. Food preservation becomes challenging given the amount of additional moisture and heat produced when canning: “In the summer, notwithstanding the heat wave, with 17 people living in an energy efficient home cooking a turkey or a fish, or canning for four hours, heats the inside buildings which is trapped. So how do you cook during an extreme heat event?” asked Patrick. An outbuilding that allowed cooking outside was utilized by some families, which is crucially important for food self-sufficiency.

The rural response to heat and access to cooling

We found that Interior communities were more accustomed to extreme heat when it comes to the built environment and air conditioning, given the experiences with heat in the past. We review these strategies for homes and at a community level.

Access to cool environments in communities

“We had thrived at 42°- 43° C before; we had a life. What we didn’t know yet was how to survive 50+° C. And the answer was, hunker down, and don’t go outside. It too shall pass.” ~ Patrick Michell, Kanaka Bar Indian Band, Lytton resident

Historically, across the communities, when the summer heat arrived, people went to the water. Lakes, creeks, rivers have been the “nature-based solutions” that provided much needed respite and brought families and communities together. As Patrick shared: “For my community, we all went to the creek. By 11 am, when it got hot, we would sit in creeks.”

However, with climate change these traditions are increasingly challenged: “The problem is by June, Lytton Creek is now no longer flowing, so you don’t have the surface water of Lytton Creek. You can go down to the Fraser and Thompson, but the Fraser and Thompson as a river system is now hitting 20 – 23° C. That’s bathwater. So, where’s the relief?” Patrick questioned.

“We live right on the lake, so we always had the water and the river to keep us cool. But the water felt like bath temperature [during the heat wave], even in the middle of the lake. It would normally be cooler because of the flow of water, but it was brutal out here.” ~ Sheri Lysons, Adams Lake Indian Band

Some relief came in the form of cool community spaces. In Adams Lake Indian Band and in Lil’wat Nation, cooling centres at the band office, health centre or other designated buildings were open during office hours, or until 8 p.m. – 9 p.m. at the latest. Cooling centres were trusted community spaces and were used by Elders to visit with each other. Unavailability of cooling outside of office hours was a limitation especially given hot nighttime temperatures. At Kanaka Bar Indian Band, a community building entry code was provided so that people could access the cool environment 24 hours/day. During the heat emergency, the building was staffed at night to help people.

Access to cooling in homes

The 2021 heat was particularly unbearable for Interior communities because there was no relief during the night, especially in the Lytton area. As Patrick shared: “Normally when we hit 42° C, nighttime temperatures dropped to the twenties. We had high thirties at night during the heat emergency. There was simply no cooling off.” High temperatures throughout the night present a major risk factor for heat-related mortality risk (He et al. 2022).

As heat began blanketing the Interior, kinship systems were activated and those with air conditioning housed family members who did not have it: “My daughter, my grandkids, and my son were staying at my house because I had the air conditioner,” shared Sheri.

Recently in communities, an effort has been made to build energy efficient homes that have a better insulated building envelope. The challenge was that without an air flow system these homes trapped heat, especially at night. “The bedrooms are upstairs where it was most hot. The house was muggy inside. We were sweating inside as if we were playing sports,” shared Casey Gabriel, Fire Captain, Lil’wat Nation. People living in homes with basements fared much better as the basements provided relief at night, some suggesting that “it was 50 per cent cooler.”

The remote experience: Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk Nation)

“Salmon is our main source of food, and it is on the brink of extinction. It’s like that on the whole coast. Skinny bears. We’re all feeling the effect of global warming.” ~ Haíɫzaqv participant

Impacts on land, waters, and food

The Haíɫzaqv community of Bella Bella, on Campbell Island, off the central coast of British Columbia is a coastal community that has sustained themselves for the past 9,000 years with gifts from land and waters. Climate change and extreme heat are fundamentally changing the Nation’s ability to feed themselves:

“A few years ago, we had heat waves two or three summers consecutively. A lot of salmon were dying. They weren’t making it into the rivers. There was no water for them to spawn. And ever since, with the climate change, our salmon populations are almost extinct.” ~ Randy Carpenter, Heiltsuk Emergency Coordinator

The heat had an impact on drinking water and water for public works:

“Our dam was very low. I think they dredged out between 100 and 150 truckloads. Now we do have a lot of water. We can probably go 4-6 months without rain, and we will still have water.” ~ Randy Carpenter, member of the Heiltsuk First Nation

The heat affected cultural continuity: from an inability to hold cultural ceremonies to disrupted food preservation activities, making it impossible to can or smoke food indoors or outdoors, due to heat and fire bans:

“Heat wave meant that we couldn’t have fires, which meant there couldn’t be traditional barbecuing of fish, which meant there couldn’t be processing, saving, or storing of fish.” ~ Haíɫzaqv participant

Response to heat and access to cooling in community

For Haíɫzaqv the heat had major impacts on infrastructure and services. As a remote community dependent on the local airport for critical supplies, heat became a factor in operations. As temperatures heated up, the air became less dense, making it harder to take off and land safely especially on a short single runway:

“[Less lift due to heat] means you can take less fuel, less people, less everything. The heat also affects landing weight which is a great impact on our community, if something needed to be brought in an emergency or out… There were also people in neighbouring communities that were very dependent to get certain medication to stay alive… It was hard to get their meds in the heat wave.” ~ Kathy Sereda, Haíɫzaqv participant

As a remote community, the Nation developed a truly relational approach to emergency planning by bringing together a 21-member emergency preparedness committee:

“It’s got everybody in our community: fire department, hospital, health transfer building, school, RCMP, Coast Guard Auxiliary, a Councillor, a health and safety officer from Tribal Council, a person from housing reconciliation, finance, communication. We are strong in that we regularly meet 6-8 times a month.” ~ Randy Carpenter, member of the Heiltsuk First Nation

During the 2021 extreme heat emergency, none of the community buildings had air conditioning as 2021 temperatures were unprecedented in the territory. At the time of the sharing circle in winter of 2023, the Nation was working to resolve this issue. As Randy noted: “We will be prepared before the summer. We will have a building in place, and we will have air conditioners. We will be ready for if we have extreme heat coming up [this] summer.”

Access to cooling in homes: Haíɫzaqv Climate Action

“To be Haíɫzaqv is to act and speak correctly, as human beings in balance with the natural and supernatural world; to live in accordance with our ǧvi̓ḷás (traditional laws). Living up to our responsibilities means taking immediate and meaningful action on climate change.” (Haíɫzaqv Climate Action 2023)

H̓íkila qṇts n̓ála’áx̌v (Protecting our World) and the Haíɫzaqv Climate Action plan has been celebrated across B.C. and Canada. Born in response to a fuel spill which destroyed 60 per cent of the community’s clam beds and fish, the plan is aimed to remove diesel dependency for the community. A heat pump project is ensuring that homes are warm in the winter and cool in the summer: “There’s a new initiative in town where we’re changing fuel. I believe there’s probably between 150 and 200 homes in the last couple of years that have went from fuel and wood, to just electricity” (Haíɫzaqv participant). As well as preparing the community for extreme heat, fuel switching has also had a positive impact on affordability and emissions: reducing average annual costs of $3,600 per home for heating and electricity by more than $1,500. One home switching to heat pumps eliminates five tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually and reduced fuel consumption by 2,000 litres of diesel per home per year (Haíɫzaqv Climate Action 2023).

Recent community growth coupled with fuel switching is putting pressure on the power lines. Historically, the community has seen prolonged recurring power outages that are very stressful for community members as they rely on power both in the winter for warmth and in the summer to cool homes.

“There’s a lot of heat pumps in and they draw a lot of power when they start up. We’re going to be expanding and installing more heat pumps this spring. Something that we need to keep in mind is our power lines. Are they adequate enough to be using that much power and what are the effects that are going to happen?” ~ Ralph Humchitt, Haíɫzaqv participant

Discussion and recommendations: A lot more work needs to be done

“Give people the truth if you want them to adapt.” Patrick Michell

Across communities, the environment is changing drastically with dire impacts on land, waters, as well as human and non-human life. The B.C. extreme heat emergency of 2021 created a terrifying new threshold beyond anything previously experienced with changes that will “be affecting us for generations,” as Sheri shared.

We observed similarities and differences within our focus on urban, rural, and remote communities. In urban settings, there was an opportunity to leverage hotels for housing Elders during the heat. In rural communities in the Interior, air-conditioning in homes was more prevalent given previous experiences with heat. In a remote setting, at the time of the 2021 heat wave none of the Haíɫzaqv community buildings had air-conditioning given the historically moderate climate.

Our case study limitations include an on-reserve focus only. More research is needed to understand Indigenous experiences with heat for off-reserve populations, especially insecurely housed, the homeless, and people experiencing mental health and substance use.

To be Indigenous is to be resilient: Culture is protective

Culture is foundational to Indigenous life and is an inherent source of strength. It is a grounding element in intrinsic Indigenous values that are placed on family, community, language, and land. Throughout each of the case studies, the protective role that culture plays in relation to extreme heat events emerges through the narrative regarding the care of Elders, the relationship to the land, ties to traditional foods, and the collective action of community.

Our case study offers a counter narrative to experiences with heat in B.C. While extreme heat outcomes are often assessed as a result of individual socio-economic and health conditions (thus placing the focus on the individuals in vulnerable conditions) our case study demonstrates that these outcomes also depend on the values of the society. For example: When Elders are valued, they are protected. Despite some Elders living in substandard housing, facing health challenges, and lacking access to air conditioners in their homes, a kinship and community care-based systems proved effective in activating informal and formal resources to ensure safe outcomes.

Recommendations:

- Approach Indigenous resilience planning by centring on Indigenous rights, the relevance of Indigenous Knowledge and language, the presence of Indigenous institutions of governance and the intergenerational strength of culture. Investments in culture are investments in resilience. Tangible investments need to be made available that allow for the nurturing of culture (e.g., at a neighbourhood or broader societal level) where Elders are visible, valued, and cared for as this can ensure safer outcomes.

- Implement trauma-informed approaches to heat response planning. While all of the communities prioritized Elders in their response, this was not easy (e.g., due to lack of cool spaces at night and mobility issues for using “Mother Nature’s cooling centres” such as lakes and rivers). Another big challenge voiced by communities was the Elders’ desire to be independent. Participants shared that Indigenous stoicism (“others need help more than I do”), as well as shame and stigma brought by colonial services were also barriers for seeking help. Heat response planning needs to be trauma-informed at the community level and a broader system level.

The compounding nature of disasters and trauma: Fear now lives within communities

Across the communities, there were very strong distinctions between impacts of the 2021 heat wave and the subsequent compounding disaster events that followed. For the Nlaka’pamux Nation, the impacts of a wildfire that devastated Lytton and Lytton First Nation as well as homes of some Kanaka Bar Indian Band residents, are still felt to this day due to displacement and inability to return. This wildfire devastation, somewhat like the one that Ashcroft Indian Band experienced in 2017 wildfire, has left communities in profound fear. This fear is triggered by the ever-increasing frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, increased winds, and drought conditions.

There is a tendency in emergency management and public policy to focus on the event that has just passed. There is also a tendency to focus on hazard specific planning that results in silos. While the documented strengths and solutions emerged at the community level, this is not sufficient for addressing long-term compounding effects of heat, subsequent drought, wildfires, extreme smoke, animal displacement, as well as tree and animal mortality. The root causes of these compounding disasters and existential fear that they bring lie far beyond the Indigenous territories where the impacts are felt the most.

Recommendation:

- Acknowledge and plan for distinct strengths, vulnerabilities, and needs of urban, rural, and remote First Nations communities. Remove hazard-specific planning silos. Plan for extreme heat and compounding effects at a watershed, provincial, and federal level. Invest to better understand the complexities tied to the compounding effects that intersect with extreme heat.

Invest in site specific data, “build homes that will last for future generations”, and reduce an over-reliance on the grid

Our case study shows that heat response plans need site-specific data at a community level given the vast differences in geography and recorded temperatures across B.C. from semi-deserts in the interior to coastal rainforests. In Lytton, the weather station’s temperature records differ from what people recorded in their vehicles and house thermometers. The weather stations placed in cooler locations may not account for the fact that localized temperatures may be hotter in some areas due to radiant heat trapped in buildings or natural features such as canyons. It is unclear whether the weather stations were updated to be able to measure the extremes. In addition to temperature, key factors like humidity, air movement, and radiant heat must be considered. Provincially available climate data sets (e.g., BC Station Data – Provincial Climate Data Set) need to be made accessible to communities in a way that can be used for planning without requiring highly specialized technical knowledge. Provincial and federal governments funding streams could be created to support investments site specific climate monitoring at the community level. This would ensure a solid basis for adaptation.

While this case study focused on the extreme heat of 2021, the participants spoke of numerous events experienced since and the importance of addressing both extreme heat and extreme cold, especially in the context of power outages. At regional and provincial scales, power outages, serviceability during extreme events, and potential for large-scale prolonged system failures need to be considered. At a community level, energy poverty and unaffordability of cooling, especially for people living with disabilities or on social assistance must be addressed. Colonial policies resulted in “one size [does not] fit all” homes that are overcrowded (not designed around intergenerational living), are poorly built and poorly insulated (using substandard materials), and not built for local climates.

Recommendations:

- To ensure climate resilient homes and to counteract an over-reliance on energy for cooling, build for local climate using site-specific data and place-based approaches. Passive design elements (that do not rely on energy to stay cool) could help ensure that houses stay safe during power outages in extreme heat.

- Develop better measures of success when it comes to extreme heat planning. Is it about 100 air conditioners in 100 homes in which case the onus and cost of running them for keeping safe is placed on the most heat vulnerable? Is it about moral responsibility to look after your neighbour? Is it about the legal responsibility of landlords to ensure safe housing? Is it about combatting a culture of individualism, loneliness, isolation, and social neglect?

Conclusion

The experiences with the 2021 extreme heat emergency described in this case study provide a glimpse into the vulnerabilities and strengths held within communities. Our case study shows that from an Indigenous perspective the impacts of the 2021 heat emergency on land, waters, and people are felt to this day. With extreme heat emergencies now considered hazards that all communities need to plan and prepare for, Indigenous wisdom must be considered a central part of the collective solution for enhanced resilience. The case studies brought forward in this work provide applied solutions and enable the development of policy recommendations for enhanced resilience across Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

Artist Statement from Sheri Lysons:

“When I was asked to paint my interpretation of climate change I had a much different image in my head. I started about 8 different paintings and none of them worked the way I envisioned. I fought to pull it together and it just wouldn’t come. At one point I felt like it was beyond my capabilities. Then it came to me, the medicine wheel, when mankind is out of balance everything suffers. Right now we are looking at a planet in crisis. We are experiencing extreme heat, fires, floods and destruction on a monumental level. To heal our planet we need to heal the water. These paintings are meant to show hope and healing.” – Sheri Lysons

References

BC Coroners Service. 2022. Extreme heat and human mortality: A review of heat-related deaths in B.C. in summer 2021. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/extreme_heat_death_review_panel_report.pdf

Favrholdt, K. 2022. “The Secwépemc c7ístkten or winter home” Kamloops This Week. https://www.kamloopsthisweek.com/community/history-the-secwepemc-c7istkten-or-winter-home-5627603#:~:text=Among%20the%20Interior%20Salish%20peoples,by%20the%20Secw%C3%A9pemc%20as%20c7%C3%ADstkten. (July 26, 2022).

Gabriel, C., Henry, S. and Yumagulova, L. 2019. “Preparing our Home: Lessons from Xeťólacw Community School, Lil’wat Nation” http://preparingourhome.ca/lessons-from-the-xetolacw-community-school/

Government of Canada. 2019. Budget: GBA+: Chapter 3. – Redressing Past Wrongs and Advancing Self-Determination. https://www.budget.canada.ca/2019/docs/plan/chap-03-en.html

Hahmann and Kumar. 2022. “Unmet health care needs during the pandemic and resulting impacts among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363349826_Unmet_health_care_needs_during_the_pandemic_and_resulting_impacts_among_First_Nations_people_living_off_reserve_Metis_and_Inuit_StatCan_COVID-19_Data_to_Insights_for_a_Better_Canada

Haíɫzaqv Climate Action. 2022. Heat Pump Project. https://heiltsukclimateaction.ca/heat-pump-project

Harris, C. 2002. Making native space: Colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia. UBC Press.

He, C., Kim, H., Hashizume, M., Lee, W., Honda, Y., Kim, S. E., & Kan, H. 2022. “The effects of night-time warming on mortality burden under future climate change scenarios: a modelling study.” The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(8), e648-e657. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00139-5/fulltext

Lil’wat Nation, 2023

Olsen, S. 2016. ”Making poverty: A history of on-reserve housing programs, 1930-1996” (Doctoral dissertation). https://fnhpa.ca/_Library/KC_BP_1_History/Making_Poverty.pdf

Samuelson, H., Baniassadi, A., Lin, A., González, P. I., Brawley, T., & Narula, T. 2020. “Housing as a critical determinant of heat vulnerability and health.” Science of the Total Environment, 720. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969720308068

Statistics Canada. 2021. Housing conditions among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada from the 2021 Census. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021007/98-200-X2021007-eng.cfm