Summary

The health of each person across Canada is shaped by the economic and social circumstances of their life. In the coming years, the health of people in Canada will also be shaped by the impacts of climate change, such as rising temperatures, air pollution and climate hazards.

Climate change adaptation policy does not regularly reflect a key concept: that climate change impacts are not equitable, and that most risks are created by society, not the physical environment.

In order to develop more robust and equitable climate policies, it is important that decision makers understand how climate impacts, environmental racism, and structural determinants of health intersect to shape health and well-being, especially in Indigenous, Black, and other racialized and marginalized communities.

This case study illustrates how structural determinants of health are interconnected with climate change vulnerability and environmental racism in two Nova Scotia communities: African Nova Scotians and Mi’kmaw.

Introduction

In the coming years, climate change will increasingly have negative impacts on people’s health across Canada. In order to reduce these health impacts—which communities are already starting to experience—evidence-based adaptation policies are needed. However, adaptation policies are not always as rigorous and evidence-based as one would hope.

Climate change adaptation policies in Canada tend to neglect two important concepts. First, climate change impacts are not equitable, meaning most risks are created by society, not nature. Second, the main determinants of health are, in fact, caused by structural factors such as race, immigrant and refugee status, poverty, education, food security, and access to clean air, water, and soil.

Consideration of how structural determinants of health, climate impacts, and environmental racism intersect to shape health and well-being is key to developing robust climate policy and building greater resilience.

In this case study, I highlight some of the most pressing structural determinants of health in Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities, drawing on literature and case studies from the research and advocacy I have been involved in with these communities over the last nine years.

The communities profiled in this case study are illustrative of a broader story of racism, health inequality, and the impacts of climate change, which will play out not only across Nova Scotia but across Canada. The stories and findings from these communities help to articulate the relationships among climate change and racial and class inequality.

Structural determinants of health impact climate change sensitivity

The concept of the structural determinants of health is increasingly being used to refer to the social, economic, political, and environmental conditions that contribute to illness and disease (De Leeuw, Lindsay & Greenwood, 2015; Waldron, 2018a, 2019). The concept of structural determinants builds on the idea of social determinants of health, which is that health is shaped by an individual’s material circumstances, such as living and working conditions (Davidson, 2015). A structural determinants framework takes a more systemic focus. The material conditions of health are rooted in systems outside an individual’s control (economic and social policies, the justice system, etc.) that have historically discriminated against racialized and marginalized people (De Leeuw, Lindsay & Greenwood, 2015; Waldron, 2018a, 2019).1 For example, lack of access to medical care in rural African Nova Scotian communities until the late 1930s, a legacy of diseases contracted by early African settlers, and racial discrimination dating back to slavery in Nova Scotia contribute to ongoing health disparities between African Nova Scotians and other populations.

“Income makes you healthy. Because I notice when you live in poverty, you tend to not be able to eat well or afford your prescriptions. And that happens a lot with the seniors in the community. So, if there are no jobs available, how are they going to eat tomorrow or how are they going to support their families and themselves and make sure they have okay health if they can’t get their medicine? And that also causes depression, and it causes anxiety and stress. And stress does bother you and it does kill you.”

In a study conducted recently, a participant from the African Nova Scotian community of Lincolnville discussed the relationship between health and poverty, food security, employment, and access to health services (Waldron, 2016).

Income and employment are key structural determinants of health because they influence access to adequate housing, healthcare, and food. Both Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities experience higher poverty rates and income instability. Frank and Saulnier (2017) report that poverty rates tend to be higher in predominately African Nova Scotian communities, such as East Preston and North Preston, where 38.9 per cent and 40 per cent of families, respectively, live in poverty. The unemployment rate for Mi’kmaw people living on reserve in the 2006 census was 24.6 per cent, compared to 9.1 per cent for all Nova Scotians (Office of Aboriginal Affairs n.d.; Statistics Canada 2011; Waldron, 2018a).

Criminalization and discrimination through the justice system are part of the social and economic conditions that influence health. Between 2014 and 2015, about 12 per cent of youth sentenced to a youth correctional facility and seven per cent of adults sentenced to jail were Mi’kmaw – although Mi’kmaw people represent only about 4 per cent of the total population (Luck, 2016). The 2019 Wortley Report on street checks revealed that African Nova Scotians were six times more likely to be stopped by police than white people (Wortley, 2019). Higher rates of criminalization are informed by racist stereotypes and result in racism and violence directed towards racialized people at all stages of the criminal justice system. Incarcerated people in Canada have higher rates of many negative health outcomes, such as mood disorders, communicable diseases, and mortality, especially death by suicide (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2016).

Education is strongly connected to employment and income security and, consequently, to the ability to access the resources that contribute to health and well-being, such as food security and housing security. Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotians are less likely to finish high school or attend university than other Nova Scotians. Of African Nova Scotians aged 25–64 years, 77.7 per cent have some sort of certificate, diploma, or degree, compared to 85.3 per cent of all Nova Scotians (African Nova Scotian Affairs n.d.). Twelve per cent of the Mi’kmaw population between the ages 25–64 holds a university degree, compared to 20 per cent in the general population (Office of Aboriginal Affairs n.d.; Statistics Canada 2011).

It is also becoming more widely recognized that stress and trauma from racism itself negatively impact the health and well-being of racialized people, even in the absence of other risk factors (McGibbon, Waldron & Jackson, 2013). The Canadian Public Health Association states that systemic racism, although subtle, causes harm in every aspect of life and is correlated with poorer health outcomes for racialized communities, such as hypertension, infant low birth weight rate, heart disease, diabetes, and mental health (CPHA, 2018).

Structural inequities like poverty and discrimination contribute to poor health outcomes for many racialized and marginalized people. Poor overall health, in turn, makes these communities more susceptible to the negative health impacts of climate change.

Structural determinants impact exposure to climate hazards

Indigenous, Black, and other marginalized communities in Canada and around the world are more exposed to the impacts of climate change (Simmons, 2020). They are more likely to reside in places where they are impacted by poor air quality and water contamination from polluting industries, as well as future climate devastation resulting from rising sea levels, raging storms and floods, and intense heat waves (United Nations, 2019).

Environmental racism helps to explain the unequal impacts of hazards. Environmental racism is the idea that marginalized and racialized communities disproportionately live where they are affected by pollution, contamination, and the impacts of climate change, due to inequitable and unjust policies that are a result of historic and ongoing racism and colonialism (Konsmo & Kahealani, 2015; Pulido, 1996). Furthermore, marginalized communities often lack political power for resisting the placement of industrial polluters in their communities through their exclusion from many environmental groups, decision-making boards, commissions, and regulatory bodies (Cryderman et al., 2016; Deacon & Baxter, 2013; Scott, Rakowski, Harris & Dixon 2015; Waldron, 2018a, Waldron 2018b).

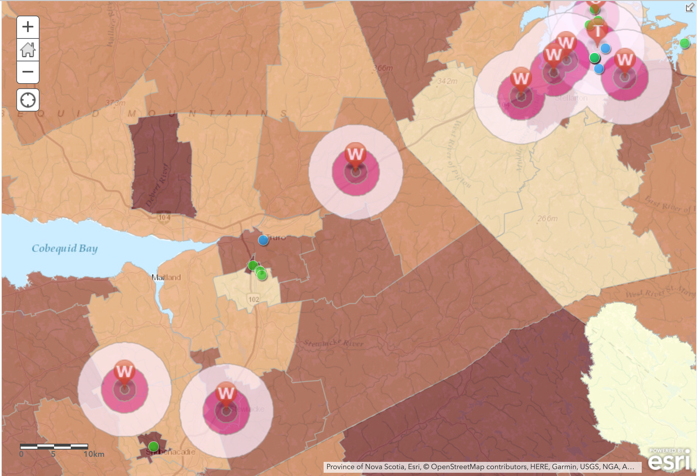

Epidemiological studies increasingly link diseases like cancer, skin conditions and reproductive health in Indigenous, Black, and other racialized communities to their disproportionate exposure to pollutants, contaminants, and climate hazards. The ENRICH Project map, developed by my research team, identifies different polluting industries and other environmental hazards in Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities across Nova Scotia, demonstrating the proximity of waste incinerators, waste dumps, thermal generating stations, and pulp and paper mills near these communities, as well the harmful materials contained at these sites that are linked to health risks.

A feedback loop exists between exposure and sensitivity

Structural determinants of health and environmental racism are deeply connected. These two factors work together to make racialized and marginalized communities more exposed and more sensitive to the impacts of climate change.

Racist and colonial legacies have created lasting health inequities in many marginalized communities, making them more sensitive to climate impacts. Further, because of environmental racism, many marginalized communities will be more exposed to climate hazards that could affect their health.

Recognizing and addressing how structural health inequities and environmental racism make marginalized communities more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change can make for stronger, more equitable climate policy.

The following sections examine some of the most significant structural determinants of health in Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities that result from social, economic, political, and environmental inequities.

Structural Determinants of Health in Mi’kmaw Communities

The Mi’kmaw, or Lnu, are the founding people of Mi’kma’ki (what is now known as Nova Scotia), having existed in the province for over 11,000 years (Sipekne’katik n.d a). The Mi’kmaw land stretches from the Canadian Maritimes to the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec (Sipekne’katik n.d.a). It is comprised of thirteen bands/First Nations, each of which is governed by a chief and council. The largest of the thirteen bands in Nova Scotia are Eskasoni (4,314 members) and Sipekne’katik (2,554 members) (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2014; Sipekne’katik. n.d.b).

Structural inequities within education, employment, criminal justice, the environment, and other social structures contribute to poor health and mental health outcomes in Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia and other Indigenous communities in Canada.

Land use planning and development policies have resulted in Mi’kmaw communities being disproportionately exposed to polluting industries and other environmental hazards. There have been several cases of environmental racism in Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia, which are highlighted in this section.

Sydney, Cape Breton

The Sydney Tar Ponds was a hazardous waste site on Cape Breton Island that sparked some of the first concerns about environmental injustice in Canada. The estuary at the mouth of the Muggah Creek where it joins Sydney Harbour used to be a hunting and fishing ground for the Mi’kmaw. From 1901 through 1988, Sydney Steel Corporation’s now decommissioned steel mill operated in the area with no pollution controls. Over a million tons of particulate matter were deposited and several thousand tons of coal tar were released into the estuary over that period, including chemicals known to cause cancer (Lambert, Guyn, and Lane 2006). As a result, Sydney area residents experienced a local cancer rate 45 per cent higher than the Nova Scotia average, and the highest rate in Canada (Nickerson 1999).

The Sydney Steel Corporation produced significant amounts of toxic waste, yet very little money was invested to modernize the facilities or to address the health and safety concerns of the workers (Campbell, 2002). In 1974, Environment Canada found that air pollution from the coking operations was 2,800 to 6,000 per cent higher than national standards allowed (Barlow and May, 2000). As Campbell (2002) documents, there were several attempts over the years to remediate this former industrial site. Concerns were raised in 1980 about the need to address the environmental risks of steelmaking in Sydney after the federal fisheries department discovered that lobsters in Sydney Harbour had high levels of carcinogenic chemicals and various toxic metals such as mercury, cadmium, and arsenic (Campbell, 2002).

In May 2004, the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia announced that they would commit $400 million over the next ten years to remediate the Sydney Tar Ponds site to reduce the ecological and human health risks to the environment (Walker, 2014). The cleanup was completed in 2013 with the development of Open Hearth Park, which is situated on the site of the former steel plant (Morgan, 2015).

Pictou Landing First Nation

Boat Harbour, a quiet estuary near Pictou Landing First Nation, was once a fertile hunting and fishing ground until 1967, when an effluent treatment facility for the Northern Pulp mill started discharging pulp and paper mill biproducts into Boat Harbour under a provincial agreement (Idle No More 2014; Thomas-Muller 2014; Waldron, 2018a). The ecological and health costs associated with the dumping of billions of litres of untreated effluent and other industrial contaminants into Boat Harbour have been considerable. Boat Harbour has the third-highest cancer rates per capita of all health districts in Canada (Mirabelli & Wing 2006; Soskolne & Sieswerda, 2010). Other studies have concluded that there is a likely connection between the mill and high rates of respiratory disease in Pictou Landing (Reid, 1989). In addition to respiratory illness, the incidence and abundance of other health problems such as nose bleeds and cancers can also be partly attributed to years of bleached kraft pulp mill pollution (Reid, 1989).

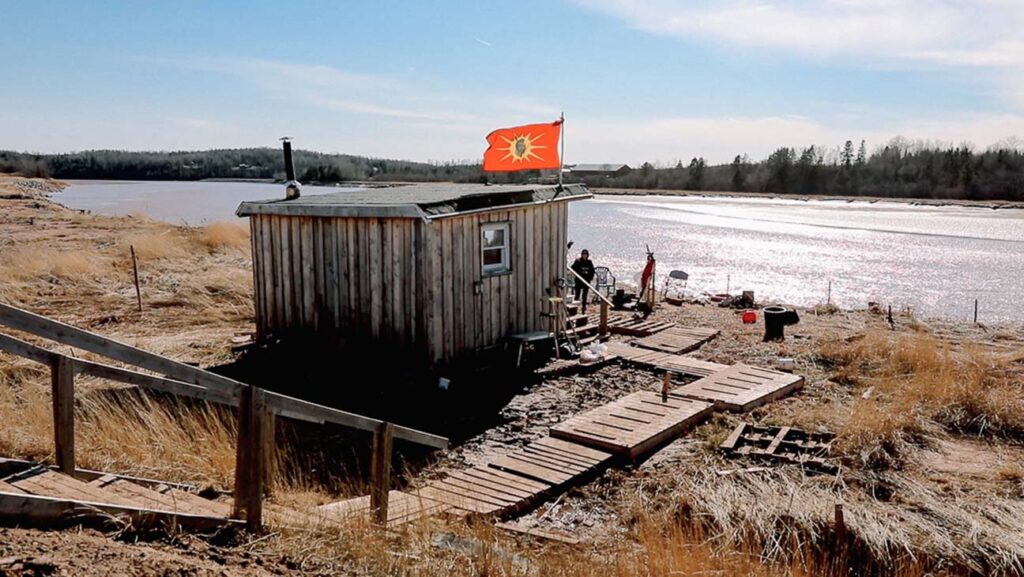

Sipekne’katik First Nation

Sipekne’katik First Nation in Hants County near Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, is currently opposing the development by Alton Natural Gas Storage of a brine discharge pipeline next to the Shubenacadie River (Hubley, 2016; Waldron, 2018a, 2021). The brine discharge pipeline would allow natural gas to be stored in underground salt caverns near the Shubenacadie River. Failure rates for salt cavern liquid natural gas projects have been high in the United States and are considered dangerous due to risks of explosion, leaks, and emissions of gasses like methane (Howe, 2016; Hubley, 2016).

In the fall of 2014, Alton Gas began developing the brine discharge pipeline, but halted the project as local resistance grew. The project resumed in January 2016, after Alton Gas was given environmental approvals for several permits by the Government of Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia, 2016; Waldron, 2018a, 2021). Throughout 2016, resistance to the project grew even stronger. Members of Sipekne’katik First Nation argued that they were not adequately consulted, that they had never given consent for the project to resume, that they were not given enough time to review project proposals and environmental impact assessments, and that they were provided with little to no notice about public meetings where they could express their concerns about the project before it resumed (Howe, 2016; Hubley, 2016). In March 2020, a Nova Scotia judge overturned the approval for the project and ordered Alton Gas to continue consultation with Sipekne’katik First Nation (Grant, 2020).

In addition to concerns about the Alton Gas project, Sipekne’katik First Nation has been concerned for some time about contaminated water in their community. The community had access to clean water until 2012, when the community’s water table was contaminated by digging at the nearby Nova Scotia Sand and Gravel pit. During a meeting I held in 2014 (Waldron, 2014), residents spoke about the environmentally hazardous methods used by Nova Scotia Sand and Gravel to dig up and clean sand in the area. This involved digging down to the level where the community’s water table flows, resulting in the water table flowing into their site, as well as huge reservoirs of water the community was no longer able to use. The community was subsequently issued a do-not-drink advisory, after which the Department of Aboriginal Affairs began shipping water into the community. Despite this, the root cause of the problem — the pit located in the community’s backyard — was never addressed, resulting in ongoing issues with water contamination (Donovan, 2015; Waldron, 2014).

Acadia First Nation

Acadia First Nation in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, is in the southwestern region of Nova Scotia. During a meeting I held in the community in 2013, residents expressed their concerns about the health risks associated with the junkyard in their community:

“Well, in our community, our reserve is actually built on a dump, over a dump. So, when they were digging it up, trying to loosen up all of the soil, so that I could put fertilizers on it and whatnot, we actually dug up car parts that are underneath us, and I was getting some history on this. So, when the band bought that land, they bought toxic land. I don’t know what they paid for it at the time, probably three-quarters of a million dollars, I don’t know, but anyway, all that land the band bought was used for a dumping zone, for cars, it was hundreds of cars where all the housing is right now” (Waldron, 2014; Waldron, 2018 a).

The junkyard has been used as a dumping ground for car parts for over sixty years and is a source of anxiety for residents, who believe it is associated with high rates of cancer in their community (Waldron, 2014).

Sydney, Pictou Landing, Sipekne’katik and Acadia First Nations are just a few examples of the larger phenomenon of environmental racism in Nova Scotia and Canada. Climate change could impact Mi’kmaw communities in the same way that environmental racism does: by increasing the exposure of marginalized communities to hazards. Increased exposure then undermines overall health and well-being in these communities, making them more vulnerable to future impacts.

The following section highlights similar examples of environmental racism among African Nova Scotian communities.

Structural Determinants of Health in African Nova Scotian Communities

People of African descent have lived in Nova Scotia for almost three hundred years, longer than any other Black community in Canada. African Nova Scotians are descendants of African slaves and freedmen, Black Loyalists from the United States, the Nova Scotian colonists of Sierra Leone, Maroons from Jamaica, and refugees of the War of 1812. The majority of African Nova Scotians and other people of African descent continue to reside in rural and isolated communities due to institutionalized racism during the province’s early settlement (Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia n.d.; Waldron, 2018a).

Over the past 70 years, environmental racism has damaged the health of rural African Nova Scotian communities. African Nova Scotians who live near toxic sites believe that high rates of cancer in their community can be linked to these sites. In my research, I have found that African Nova Scotian communities in Shelburne, Lincolnville, and the Prestons attribute high rates of cancer, liver and kidney disorders, diabetes, heart disease, respiratory illnesses, skin rashes, and psychological stress to various environmental hazards that have been near these communities for decades (Waldron, 2014, 2015, 2016; 2018a; 2018b, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d). The following sections highlight specific cases of environmental racism in African Nova Scotian communities, including its impacts on health.

Africville

Perhaps no other African Nova Scotian community has served as more of a classic example and symbol of segregation, racism, and environmental racism than Africville. The community was located just north of Halifax on the shore of the Bedford Basin, and was first settled in the mid-1800s by Black refugees who came to Nova Scotia following the War of 1812 (Allen n.d.; Fryzuk 1996; Nelson 2001; Waldron, 2020d). The community was subjected to injustices on many levels. For example, although the City of Halifax collected taxes in Africville, they did not provide the community with basic utilities or infrastructure offered to other parts of the city, such as paved roads, potable water, sewage, public transportation, garbage collection, recreational facilities, fire protection, streetlights, or adequate police protection (Allen n.d.; Fryzuk 1996; Halifax Regional Municipality n.d; Nelson 2001; Tavlin 2013; Waldron, 2020d).

Starting in the 1800s, the city placed a number of undesirable facilities in Africville, such as slaughterhouses, an infectious disease hospital, and human waste disposal pits (Mackenzie, 1991). In 1947 the city rezoned Africville as industrial land. The rezoning permitted the construction of an open-pit dump in 1950, which many in the community considered to be a health hazard (Waldron, 2018a). In 1964, the City Council voted to relocate Africville residents in order to build industry and infrastructure in the area. By 1970, all homes in Africville had been bulldozed and residents forcibly displaced into other areas of the city (Waldron, 2020d). Africville subsequently became host to several environmental hazards, including a fertilizer plant, a slaughterhouse, a tar factory, a stone and coal crushing plant, a cotton factory, a prison, and three systems of railway tracks (Allen n.d.; Fryzuk 1996; Nelson 2001; Waldron, 2018b, Waldron, 2020d).

Shelburne

The Morvan Road Landfill has been located near the African Nova Scotian community in South Shelburne since the 1940s (Waldron, 2020d). The landfill was used for industrial, medical, and residential waste until its closure in 2016, thanks to pressure from the community (Waldron, 2018a). While the closure of the landfill is a major achievement, the presence of the landfill continues to have health and environmental repercussions in Shelburne. The waste that accumulated has not been addressed through a remediation plan (Delisle & Sweeney, 2018). A Shelburne resident who participated in my study on environmental health inequities in African Nova Scotian communities attributed high rates of cancer and liver and kidney disorders in her community to the landfill near her community.

Lincolnville

Lincolnville is another example of a long-standing case of environmental racism in an African Nova Scotian community. Lincolnville is a small rural African Nova Scotian community situated in Guysborough County in northeast Nova Scotia. It was settled by Black Loyalists in 1784 (NSPIRG n.d.). In 1974, a first-generation landfill was opened one kilometre away from the community (Waldron, 2018a). The health impacts of the first landfill are unknown, though residents believe rates of cancer in the community are far above acceptable levels (Waldron, 2018a).

“Everyone knows that in all surrounding communities the dump can be seen in the south end of the community. A significant amount of people in proximity to the dump has died from cancer and has or is suffering from an array of other health problems such as various forms of cancer, increased blood pressure, changes in nerve reflexes, brain, liver, and kidney disorders” (Waldron, 2016).

In 2006, the Municipality of the District of Guysborough closed the first landfill and opened a second-generation landfill at the site of the first-generation landfill that accepts waste from across northern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. According to regional environmental organizations, hazardous items such as transformers and refuse from offshore oil spills have been deposited at the landfill. This has caused concern in the community about unacceptable levels of carcinogens from the site—including cadmium, phenol, and toluene—leaching into the community’s drinking water (Benjamin, 2008). According to a Lincolnville resident who took part in a study I conducted, residents have experienced worsening health since the first-generation landfill was placed in the community, including increasing rates of cancer and diabetes:

“If you look at the health of the community prior to 1974 before the landfill site was located in our community, our community seemed to be healthier. From 1974 on until the present day, we noticed our people’s health seems to be going downhill. Our people seem to be passing on at a younger age. They are contracting different types of cancer that we never heard of prior to 1974. Our stomach cancer seems to be on the rise. Diabetes is on the rise. Our people end up with tumours in their body. And, we’re at a loss of, you know, of what’s causing it. The municipality says that there’s no way that the landfill site is affecting us. But, if the landfill site located in other areas is having an impact on people’s health, then shouldn’t the landfill site located next to our community be having an impact on our health too?” (Waldron, 2016)

The Prestons

North and East Preston, located in eastern Halifax Regional Municipality, represent other examples of environmental racism in the African Nova Scotian community. During the summer of 1991, the Metropolitan Authority was in search of a new landfill site for Halifax and Dartmouth. Included in the top choices were four areas that were close to historically African Nova Scotian communities. When the Metropolitan Authority eventually settled on East Lake as the new landfill site, African Nova Scotian residents in East and North Preston were outraged (Fryzuk, 1996; Waldron, 2018). Residents of the Prestons opposed the decision to site the landfill in East Lake by launching a formal complaint against the landfill site selection process, arguing that the Metropolitan Authority failed to consider social, cultural, and historical factors in their decision-making process.

A North Preston resident who took part in a meeting I held in 2013 shared her concerns about the relationship between water and air pollution from the waste disposal site near the North Preston Community Centre and high rates of cancer, diabetes, heart disease, respiratory illnesses, and skin rashes in the community:

“For years, part of the community was on a water system which was not flushed out for several decades because the chemical treatment of that water supply was monitored … but I believe that there were too high concentrations of chlorine in the system. So, I think that accounts for the high cancer rate over the last several decades. I also believe that in terms of environmental health, that it’s poor because of our community being associated with a local dump. And therefore, a lot of the fly ash in the air contributed to the high rate of respiratory illnesses” (Waldron, 2014).

The case studies on Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities presented here provide evidence for the link between race, polluting industries and other environmental hazards, and poor health outcomes. Other Canadian literature supports the idea that this phenomenon is not unique to Nova Scotia: across the country, racialized communities have been disproportionately exposed to health risks compared to other communities because they are more likely to be spatially clustered around waste disposal sites and other environmental hazards (Atari, Luginaah, Gorey, Xu, and Fung 2012; Sharp 2009; Teelucksingh 2007; Waldron, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018a).

Conclusion

These case studies illustrate how connected the health of Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian communities is to the air, water, and soil surrounding them. Polluting industries and environmental degradation have already harmed the health of communities and ecosystems. If decision makers fail to understand and address the ways that marginalized communities will be uniquely affected, climate change could recreate the same unequal impacts.

Decision makers and policy makers in the health and environment sectors in Nova Scotia and Canada must begin to consider approaches that can be used to address the social, economic, political, and environmental inequities that shape health outcomes in Mi’kmaw, African Nova Scotian, and other Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities. The following section offers a path forward for how policy makers and decision makers can better address the structural determinants of health in these communities.

Addressing the structural determinants of health discussed in this report can bring us closer to our goal of achieving health equity in Canada and building resilience to climate change. Health equity includes three main principles:

- Equal access to healthcare, regardless of one’s social, economic, physical, or geographical status.

- Equal opportunity for all people to be as healthy as possible, given their unique physiology.

- Equal quality of care for all describes the level of commitment that healthcare providers demonstrate in providing the same high standard of professional care to everyone, regardless of social, economic, or cultural differences (Braveman & Gruskin, 2003).

Achieving health equity and environmental justice for Mi’kmaw, African Nova Scotian, and other Indigenous and Black communities in Canada requires progressive policy change and decision making in departments of health and environment. There are several actions that these departments can take to address health inequities (including environmental health inequities) in Indigenous and Black communities.

Addressing the structural determinants of health discussed in this report can bring us closer to our goal of achieving health equity in Canada and building resilience to climate change.

First, it is crucial that departments of health and environment collect disaggregated statistical race-based data on health outcomes in Indigenous and Black communities and on the location of environmental hazards across the country.

Second, health departments must increase representation of Indigenous and Black people by hiring more Indigenous and Black health professionals and recruiting them to sit at decision making tables as managers and policy makers where upstream changes are made.

Third, it is important that environmental justice legislation is passed that encompasses tools, strategies, and policies focused on eliminating unjust and inequitable conditions and decisions that result in differential exposure to, and unequal protection from, environmental harms.

Finally, a health equity impact assessment must be incorporated into the environmental assessment and approval process to examine and address the cumulative health impacts of environmental racism in Indigenous and Black communities that are outcomes of long-standing social, economic, political, and environmental inequities.

Dr. Ingrid Waldron is HOPE Chair in Peace and Health at McMaster University and the co-producer of the Netflix film based on her book There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities.

Resources from the Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health Project (The ENRICH Project)

The Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health Project (The ENRIC PEwebsiteENRICH Project): https://www.enrichproject.org/

Dr. Ingrid Waldron’s book There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous & Black Communities: https://fernwoodpublishing.ca/book/there8217s-something-in-the-water

The ENRICH Project Donation Page at MakeWay: https://makeway.org/project/the-enrich-project/

The National Anti-Environmental Racism Coalition Donation Page at MakeWay: https://makeway.org/environmental-racism/

Trailer for the Netflix documentary film There’s Something in the Water, based on Dr. Waldron’s book and co-produced by Waldron, Elliot Page, Ian Daniel and Julia Sanderson, and directed by Elliot Page and Ian Daniel: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/theres-something-in-the-water-ellen-page-documentary-954952/

In Whose Backyard documentary, co-produced by Pink Dog Productions and Dr. Waldron: https://www.enrichproject.org/resources/#IWB-Video

The ENRICH Project Map: https://www.enrichproject.org/map/

The ENRICH Project’s Africville Story Map: https://dalspatial.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=d2e8df48f88e4ddc90ebe494a2cfa2a1

References (click to expand)

Akerlof , K. L., P. L. Delamater, C. R. Boules, C. R. Upperman, and C. S. Mitchell. 2015. “Vulnerable populations perceive their health as a risk from climate change.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(12), 15419-15433.

American Psychological Association, Climate for Health & EcoAmerica. 2017. Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf

Atari, D.O., L. Luginaah, K. Gorey, X. Xu, and K. Fung. 2012. “Associations between self-reported odour annoyance and volatile organic compounds in ‘Chemical Valley’, Sarnia, Ontario.” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 185, 6: 4537–49.

Barlow, M. and E. May. 2000. Frederick Street: Life and Death on Canada’s Love Canal. Toronto: HarperCollins.

Benjamin, C. 2008. “Lincolnville dumped on again.” The Coast. August 7. thecoast.ca/halifax/lincolnville-dumped-on-again/Content?oid=993619 (accessed March 4, 2013).

Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. n.d. “Black Migration in Nova Scotia.” bccns.com/our-history/

Braveman, P. A. and S. Gruskin. 2003. “Defining equity in health.” Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 57, 254-258.

Bullard, R.D. 2002. “Confronting environmental racism in the 21st Century.” Global Dialogue: The Dialogue of Civilization, 4: 34–48.

Campbell, R.A. 2002. “A narrative analysis of success and failure in environmental

remediation: The case of incineration at the Sydney Tar Ponds.” Organization and Environment, 15 (3): 259–77.

Canadian Public Health Association. 2018. Draft position statement: Racism and public health. https://www.cpha.ca/racism-and-public-health.

Cryderman, D., L. Letourneau, F. Miller, and N. Basu. 2016. “An ecological and human biomonitoring investigation of mercury contamination at the Aamjiwnaang First Nation.” EcoHealth, 13, 4: 784–95.

Davidson, A. 2015. Social determinants of health: A comparative approach. Toronto: Oxford.

Deacon, L. and J. Baxter. 2013. “No opportunity to say no: A case study of procedural environmental injustice in Canada.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 56, 5: 607–23.

De Leeuw, S., N. M. Lindsay, and M. Greenwood. 2015. “Rethinking determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada.” In M. Greenwood, S. De Leeuw, N. M. Lindsay and C. Reading (Eds.), Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: Beyond the Social (pp.xi-xxix). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Delisle, L. and E. Sweeney. 2018. “Community mobilization to address environmental racism: The South End Environmental Injustice Society.” Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative & Relational Ethnic Studies, 5 (2), 313-318.

Donovan, M. 2015. “Will Nova Scotia take environmental racism seriously?” Halifax Examiner, July 29. halifaxexaminer.ca/province-house/will-nova-scotia-take-environmental-racism-seriously/

Durkalec, A., C. Furgal, M. W. Skinner, and T. Sheldon. 2015. “Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community.” Social Science & Medicine, 136-137, 17-26.

Frank, L. and C. Saulnier. 2017. “2017 report card on child and family poverty in Nova Scotia.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Nova%20Scotia%20Office/2017/11/Report%20Card%20on%20Child%20and%20Family%20Poverty.pdf

Fryzuk, L. A. 1996. “Environmental justice in Canada: An empirical study and analysis of the demographics of dumping in Nova Scotia.” Unpublished masters thesis. Halifax: Dalhousie University.

Halifax Regional Municipality. n.d. “Remembering Africville source guide.” Halifax Online. halifax.ca/about-halifax/municipal-archives/source-guides/africville-sources

Howe, M. 2016. “Going against the tide: The fight against Alton Gas.” The Coast. February 18. thecoast.ca/halifax/going-against-the-tide-the-fight-against-alton-gas/Content?oid=5221542

Hubley, J. 2016. “The Alton Gas project: An analysis.” Solidarity Halifax, March 31. solidarityhalifax.ca/analysis/the-alton-gas-project-an-analysis/

Idle No More. 2014. “Pictou Landing erects blockade against Northern Pulp.” June 13. idlenomore.ca/pictou-landing-erects-blockade-against-northern-pulp-mill-idle-no-more/

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. 2014. Registered Indian Population by sex and residence 2014 – Statistics and Measurement Directorate. December 31. sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1429798605785/1604601286649

Konsmo, E. M. and A. M. Kahealani Pacheco. 2015. “Violence on the land, violence on our bodies: Building an Indigenous response to environmental violence.” landbodydefense.org/uploads/files/VLVBReportToolkit2016.pdf

Lambert, T. W., L. Guyn, and S. E. Lane. 2006. “Development of local knowledge of environmental contamination in Sydney, Nova Scotia: Environmental health practice from an environmental justice perspective.” Science of the Total Environment, 368 (2–3): 471–84

Lewis, S. K. 2016. “Climate justice: Blacks and climate change.” The Black Scholar, 46(3), 1-3.

Luck, S. 2016. “Black, Indigenous prisoners over-represented in Nova Scotia Jails.” CBC News Nova Scotia, May 20. cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/black-indigenous-prisoners-nova-scotia-jails-1.3591535

McGibbon, E., I. R. G. Waldron, and J. Jackson. 2013. “The social determinants of cardiovascular health: Time for a focus on racism” (Guest Editorial), Diversity & Equality in Health & Care, 10(3), 139–42.

Mackenzie, S. (1991). Remember Africville. National Film Board of Canada.

Mirabelli, M. C. and S. Wing. 2006. “Proximity to pulp and paper mills and wheezing symptoms among adolescents in North Carolina.” Environmental Research, 102: 96–100.

Morgan, R. 2015. “We’re tired of being the dump: Exposing environmental racism in Canadian communities.” Honours thesis. Halifax: Dalhousie University.

Nelson, J. J. 2001. The operation of whiteness and forgetting in Africville: A geography of racism. Doctoral thesis. Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Nickerson, C. 1999. “Hoping blight makes might: Cape Breton Town seeks role as toxic waste learning site.” Boston Globe, May 12.

NSPRIG. N.d. Save Lincolnville Campaign. Nspirg.ca/projects/past-projects/save-lincolnville-campaign/#sthash.9YV4BKxl.dpuf

Office of Aboriginal Affairs. n.d. Facts sheets and additional information. novascotia.ca/abor/aboriginal-people/demographics/

Pulido, L. 1996. “A critical review of the methodology of environmental racism research.” Antipode, 28, 2: 142–59.

Reid, D. S. 1989. Pictonians, pulp mill and pulmonary diseases. Nova Scotia Medical Journal, 68: 146–48.

Saulnier, C. 2009. Poverty reduction policies and programs: The causes and consequences of poverty: Understanding divisions and disparities in social and economic development in Nova Scotia. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Scott, N., L. Rakowski, L. Zahra Harris, and T. Dixon. 2015. “The production of pollution and consumption of chemicals in Canada.” In D. N. Scott (Ed.), Our chemical selves: Gender, toxics and environmental health (pp. 3–28). Vancouver: ubc Press.

Sharp, D. 2009. “Environmental toxins: A potential risk factor for diabetes among Canadian Aboriginals.” International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 68, 4: 316–26.

Simmons, D. 2020. “What is climate justice?” July 29. Yale Climate Connections. yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/07/what-is-climate-justice/

Sipekne’katik. n.d. (a) “History.” sipeknekatik.ca/history/

Sipekne’katik.. n.d. (b) Community profile. sipeknekatik.ca/community-profile/

Soskolne, C. L. and L. E. Sieswerda. 2010. “Cancer risk associated with pulp and paper mills: A review of occupational and community epidemiology.” Chronic Diseases in Canada, 29 (Supplement 2): 86-100.

Statistics Canada. 2011. “Nova Scotia Community Counts, Census of Population and National Household Survey.” www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Tavlin, N. 2013. “Africville: Canada’s secret racist history.” Vice, February 4. vice.com/en_ca/read/africville-canadas-secret-racist-history

Teelucksingh, C. 2007. “Environmental racialization: Linking racialization to the environment in Canada.” Local Environment, 12, 6: 645–61.

Thomas-Muller, C. 2014. “Pictou Landing First Nation government erect blockade over Northern Pulp Mill effluent spill.” IC Magazine, June 10. intercontinentalcry.org/pictou-landing-first-nation-government-erect-blockade-northern-pulp-mill-effluent-spill-23337.

United Nations. 2019. “Climate justice.” May 31. United Nations. un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/climate-justice/

Waldron, I. R. G. 2014. Report on the regional meetings and convergence workshop for: In whose backyard? – Exploring toxic legacies in Mi’kmaw & African Nova Scotian communities. Report submitted to Nova Scotia Environment. Halifax: Dalhousie University.

Waldron, I. R. G. 2016. Experiences of environmental health inequities in African Nova Scotian communities. Report prepared for the Canadian Commission for UNESCO (CCUNESCO). Halifax: Dalhousie University.

Waldron, I. R. G. 2018a. There’s something in the water: Environmental racism in Indigenous & Black communities. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Waldron, I. R. G. 2018b. “Women on the frontlines: Grassroots movements against environmental violence in Indigenous and Black communities in Canada.” Kalfou: A Journal of Comparative and Relational Ethnic Studies, 5 (2), 251-268.

Waldron, I. R. G. 2020d. “Environmental Racism in Canada.” Canadian Encyclopedia. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/environmental-racism-in-canada

Waldron, I. R. G. 2021. “On the Shubenacadie River: The Grassroots Grandmothers and the fight against Alton Gas.” In D. P. Thomas and V. Coburn (Eds.), Capitalism & dispossession: Corporate Canada at home and abroad. Forthcoming.

Walker, T. R. 2014. “Environmental effects monitoring in Sydney Harbor during remediation of one of Canada’s most polluted sites: A review and lessons learned.” Remediation: The Journal of Environmental Cleanup Costs, Technologies and Techniques, 24, 3: 103–17.

Wortley, S. 2019. “Halifax, Nova Scotia street checks report.” Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission. humanrights.novascotia.ca/sites/default/files/editor-uploads/halifax_street_checks_report_march_2019_0.pdf

- The concept of social determinants of health, by definition, tends to exclude or marginalize other types of determinants not typically considered to fall under the category of the “social”—for example, spirituality, relationship to the land, geography, history, culture, language, and knowledge systems.