Foundations

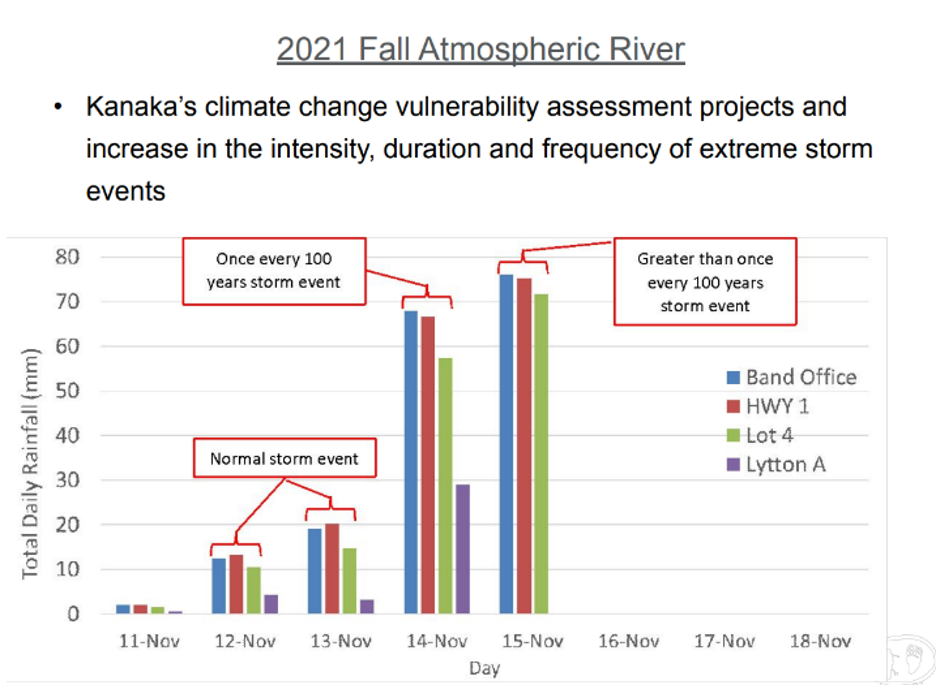

The Fraser Canyon region is the heartland of an Indigenous nation known as the Nlaka’pamux, and the town of Lytton is at the geographical centre of the Nation. In 2021, a spring and early summer drought was a precursor to a Pacific Northwest heat dome which resulted in a recorded high of 49.6° C on June 29 and the next day, Lytton burned to the ground in 21 minutes (BBC News 2021). Five months later, a regional atmospheric river wiped out all but one access road and, in December, extreme cold and deep snow paralyzed the region. While these 2021 events were unprecedented, they were not unexpected: worldwide warnings about climate impacts have been growing since the 1980s, and it is now evident that humanity is moving out of “just-right-for-life conditions”, experiencing temporary spikes of extreme weather which could become permanent with significant consequences for human health and well-being (McMichael et al. 2017).

The Lytton fire also showed that Canada exists on fragile foundations. Yesterday’s settler governments (Karl 2005) made decisions based on a “get-it-done” approach, resulting in buildings, systems, and economies that worked, but were neither sustainable nor resilient. Canada was also built over the lives, lifestyles, and objections of Indigenous populations with little regard for the adverse impacts on the environment and future generations. Previous settler government decisions were justified by a few on the premise of efficiency and pursuit of profit. Today’s governments must resolve these past wrong-doings and take a different decision-making approach for our collective tomorrow, one that is not based on “get-it-done” but on protecting people and communities, with the knowledge that climate change is real and its impacts are growing in frequency, duration, and intensity.

Governments must also address historical issues created by previous decision-makers who ignored, avoided, or off-loaded issues onto future generations. This risk remains as current governments may perpetuate a status quo mindset, not recognizing that climate impacts are real and increasingly severe or not taking action quickly enough to protect people and communities. If we do not overcome our collective paralysis on addressing climate impacts (Rand 2014) adaptation planning will be delayed until it’s too late, and we are caught in debilitating response mode. Simply put, we want to avoid doing nothing today, taking our chances, and letting tomorrow bear the brunt of impact. No one is immune from climate change’s growing impacts and when we make a conscious decision to make the environment the priority, we all benefit and, more importantly, so do our children and grandchildren.

The Fraser Canyon region’s recovery from the devastating events of 2021 is slow and not without controversy (Partlow 2022). There is a tension between building back quickly and building back better. The recovery is also constrained by a real-time process of rectifying past state decisions, decisions that off-loaded the responsibility of creating sustainable communities onto the next generation (Olsen 2023).

Integral to the recovery will be a renewed understanding of the role and functions of the physiological foundations needed for quality of life—clean air, water, food, and shelter—which must be satisfied before other needs can be met (McLeod 2018), and, more importantly, to get right in the recovery what was not done right the first time.

There are other layers to the recovery process that are sometimes not considered. Having experienced compounding trauma, residents of the region will need to overcome individual fear, anger, and sadness, which, despite the passage of time, continues to overwhelm and undermine recovery. Secondly, they will need to work together on the common goal, which is to conceptualise, design, fund, and build a community that is resilient to the weather of today and tomorrow, allowing the core needs of residents to be met even in a future that will be destabilized by further climate events.

While this paper focuses on the experience in Lytton, this is not only a Lytton problem. Across Canada, there are 62,000 communities at the same risk level as Lytton was in 2021 (Cohen and Westhaver 2022). The Lytton recovery story is thus important for all Canadians.

However, having experienced multiple extreme weather events in a very short time frame (Michell 2021), inhabitants are uniquely positioned to become one of Canada’s first resilient regions. And, if Canada’s First People are part of all conversations pertaining to land and resource use (United Nations General Assembly 2007), it will help overcome learned and reinforced behaviour and avoid the mistakes of the past. First Peoples can inform decision-making approaches so that they are focused on taking action to invest in our collective foundations and ensure that all Canadians can weather the coming storms (River Voices 2020). As early as 2010, Kanaka Bar Indian Band, one of the 15 communities that make up the Nlaka’pamux Nation, set aside intergenerational anger and resentments that had accumulated since colonization and set the community toward a new and more resilient future (Michell 2010). In 2015, the Indigenous community codified a vision statement as: “Kanaka Bar is committed to using its lands and resources to maintain a self-sufficient, sustainable and vibrant community” (Kanaka Bar Indian Band 2015), which was followed shortly by the community’s climate change impacts assessment and transition plan. What follows are insights into the decisions and actions Kanaka Bar has taken to build community resilience into the four physiological foundations—clean air, water, food, shelter, so they are prepared for the weather of tomorrow, actions that can be replicated and scaled-up in communities across the country.

Knowing the weather

For the Nlaka’pamux, living in the same place for more than 8,000 years generated a collective conscious knowledge or knowing of local and regional weather, seasonal patterns, and ecosystem cycles. In the 1980s, residents of the Fraser Canyon observed changes on the ground inconsistent with this knowing, and by 1992 a label was applied by climate scientists—anthropogenic climate change. The world’s air, land, and water are retaining heat at an unprecedented rate, producing supercharged or extreme weather events that are overwhelming thousands of years of Indigenous knowing and post-colonial infrastructure and systems that were designed for the weather patterns of yesterday. Ecosystem shifts and collapses are occurring on the ground (Chambers et al. 2021), which makes living today, and preparing for tomorrow, very uncertain. When people don’t know, they worry. Stress and anxiety created by climate change fear and impacts has been accepted globally by health officials and mental health diagnoses for climate anxiety, eco-anxiety and solastalgia1 are now on the rise.

To alleviate stress caused by uncertainty about the future impacts of climate change, the Kanaka Bar Indian Band, located 18 kilometres south of Lytton, completed a 2015 community watershed Land Use Plan (Kanaka Bar Indian Band 2015) and a 2018 Climate Change Assessment and Transition Plan (Kanaka Bar Climate Change Assessment and Transition Plan 2018) and has since invested in three weather stations, seven water gauging stations and an air quality monitor. These tools generate daily site-specific community data for air quality, wind speed and direction, temperature, precipitation, and water quantity. They complement rather than replace Indigenous knowing and assist with community forecasting, early warning systems, emergency preparedness, and response planning.

Site-specific weather monitoring helps improve warning and response plans, providing communities with as much lead time as possible to prepare for extreme weather events, so they can plan for any spikes in extreme heat, wind, rain, and cold and recover more quickly. It allows communities to know with more specificity and warning about when physiological needs are not going to be met—when their health and safety may be at risk from unsafe air, water, heat, and a risk to their shelters. Site-specific data also informs the design and building of new infrastructure or for retrofitting existing infrastructure so it is resilient to the weather in a particular region. The more weather and climate information that communities have, the better warning and response plans they will have and the safer residents will be.

Recommendation:

- All orders of government (including Indigenous, federal, provincial, territorial, municipal) should implement policies that support the pooling of resources and the sharing of information, and coordination across different orders of government should be designed and implemented to enable communities to understand regional and site-specific risks, and collectively source and install more site-specific air, wind, temperature, and precipitation stations to generate regional weather data.

Water security

Within the Fraser Canyon region, surface water streams are drying up and regional dry spells are lasting longer while demand remains consistent. Inhabitants with surface water licenses are now facing repeat “low water” and “no water” scenarios. In 2021, ground water wells were running out of water as well and while no zero days occurred—it may be coming soon.

Lytton was originally built with surface water drawn from Lytton Creek and for years has had to supplement surface supply with water pumps (from wells and from the Thompson River). When the Lytton fire ended the region’s electric supply the town and region was without water as the ability to divert, store, and generate potable water was lost.

The Fraser Canyon region is looking at a regional plan to share information and water infrastructure so that the water crisis of 2021 is not replicated.

The issue for those in the Fraser Canyon region is not water quantity given the 2021 drought and subsequent atmospheric river events (which unloaded too much precipitation all at once). The issue is planning and building new water storage that is reliable and sustainable even in the face of extreme weather events.

Nlaka’pamux communities have and continue to exist where stable and predictable sun, wind, water, and seasons have been observed to produce healthy ecosystems. Proximity to year-round fresh water sources for ecosystem health, drinking, cooking, animal husbandry, irrigation, and fire protection was where Indigenous people chose to live—thus the saying “water is life.” Nlaka’pamux life changed through contact with European explorers, and when an initial period of Indigenous-explorer mutual relations ended (Manuel and Posluns 1974), it was replaced by colonial law and policy based on denial and oppressions that existed for generations.

Once established, colonial and provincial states oversaw the allocation of fee simple land parcels (private property) to newcomers, which included water licenses which are “first in line-first in right” for purposes like drinking, irrigation, and economic benefit, with little or no thought to the original inhabitants or the ecosystems that had relied on the water for millennia. Inherent title and rights to nation lands and water were disregarded and, since federal reserve allocations came after Confederation, Indian Act reserve lands and water licenses (if available) were small, in bad locations, and not suitable for housing and agriculture. The result was most Nlaka’pamux communities were displaced and relegated to living in very poor conditions, and forced to be in response-mode to colonialism and live with the impacts of these conditions for generations.

As part of their plan, and to fulfill their vision statement, Kanaka Bar took steps to address these wrongs and to secure for their community one of the most important physiological foundations: Water. With forecasted changes in both weather and precipitation and seeing actual change occur, Kanaka Bar made investments in water gauging stations on seven surface streams within the traditional territory. With site-specific quantity and flow data received to date, Kanaka designed and built new intakes, storage, and delivery systems which can handle “too much” water scenarios and store water for timed release during winter and summer drought conditions.

Kanaka Bar’s water system is gravity-fed so water can flow during power outages. Kanaka also invested in small-scale solar, wind, and some hydro renewable electricity generation so, if needed, it can shift the energy source for the existing potable treatment plant so it can be kept running during a power failure.

Kanaka has also doubled its surface water storage based on current and short-term need forecasts and has created plans for quadrupling storage should demand increase. Finally, Kanaka has separated potable water storage and delivery systems from raw water (purple hydrants and taps) so that an ample supply of non-treated water is available for irrigation and fire protection. All the above has addressed the community’s short and medium long-term water needs and, perhaps more importantly, alleviated current eco-anxiety by giving present day and future generations knowledge that regardless of the weather, they will have a sustainable water supply, which is one of the most important physiological foundations.

To have a meaningful, realistic, and achievable climate change transition and adaptation plan requires water and while you can’t control the weather, you can mitigate its impacts. To learn from Kanaka Bar’s example, communities should consider the following when building a sustainable water security plan:

- Assumptions: Don’t take personal, community, or regional water security for granted. Communities should understand where their water source is and plan for scarcity.

- Relevant: Understand water licenses. When were they issued? Are they still applicable today? Is there still water to draw on? What are reasonable alternatives to accessing water if your supply stops?

- Quantity: Install water quantity gauging stations on surface and groundwater and get the empirical data to help forecast water scarcity and possible zero days (i.e. when there is no supply).

- Collaborate: Meet with regional “water boards” to discuss and plan for water certainty including storage, conservation, timed release, and delivery of potable water in case system failure has occurred. Share knowledge, resources, and plans to minimize shortage and expedite recovery.

- Resilient: Design, build, or retrofit physical infrastructure for the weather of today and tomorrow so that an atmospheric river or a wildfire doesn’t bring an end to the water supply.

- Hybrid systems: Examine potable water treatment options that are not dependent on the grid to work and separate out raw water from the potable water systems.

These approaches can also inform policy design and have broad implications for all Canadians and orders of government.

Food security

The Lytton fire exemplifies food fragility and security concerns. Stores were lost in the fire, roads were closed, and an extended electricity outage resulted in families, whose homes had survived the fire, losing their fridge and frozen foods. The families who had either dehydrated or canned their foods, and whose cellar and basement storage survived the fire, were okay as their food supply was not impacted by the extended electricity outage. Food donation centres were set up, but adequate supply, diversity, and quality varied with the donation. For those who can afford to travel, going to and from the urban stores has become an expensive new norm.

For more that 8,000 years, the Fraser Canyon’s climate and resulting ecosystems supplied the original inhabitants with access to fresh meats, fruits, vegetables, fish, medicines, tools, and clothing, and a language, culture, laws, and art form developed. Protocols for food harvesting, preparation, storage, and ceremony were well known and surplus was used for trade.

Colonial policy codified prohibitions on Indigenous people from accessing their traditional territory and practising their old ways, including the sale or barter of food to others (Karl 2005). These prohibitions created generations of suffering and established dependency on the state. To make matters worse, while colonial law prohibited slavery, the many generations who were forcibly removed from their families to attend residential school, were often required to toil in the fields. Concurrent to this, federal policies like the peasant farm policy in the prairies regulated agricultural production on reserve (Carter 1990). Conversations with community show that terms like farming and agriculture now carry a stigma among some Indigenous people because of these historical wrong-doings. Now that the archaic and draconian restrictions have been lifted, Indigenous people are returning to their territories where they are observing traditional foods suffering from air, soil, and water contamination, as well as heat, drought, and over-exploitation. Ecosystem shifts are now occurring in the Fraser Canyon region including the decline of the Fraser River’s wild salmon species (Chambers and Hocking 2021) and traditional field crops are struggling from drought and too much heat. Unfortunately, a shift to community or home-based gardens that could support greater food security has not yet occurred on the scale it needs to and as a result dependency on others for our food continues and will worsen as extreme weather events and impacts increase in frequency, duration, and intensity.

In 2016, Kanaka Bar did a community food assessment, and a significant finding was that there has been a shift away from community-based food systems in favour of reliance on third-party supplies and suppliers (Berezan 2016). With knowledge that today’s stores carry at most a three-day supply of essentials (when supplies are available) and when roads are closed shelves go empty, Kanaka has invested in a range of food security initiatives including controlled environment agriculture which allows the community to grow fruit and vegetables year-round regardless of the weather.

Kanaka has also cleared and serviced vacant lands in preparation for community “aquaculture” or the raising of fish proteins in lieu of depleting wild salmon stocks. Kanaka has also secured ownership of off-reserve land from farmers and owners who no longer work their properties to raise proteins that are not water intensive and don’t require a lot of feed such as rabbits, pork, poultry (all types), goats, and, in the future, fallow deer. By taking these steps, Kanaka has made significant progress on ending dependency on the grocery store. Kanaka’s surplus meats, fruits, and vegetables are also available to the region at the new community centre, which is grid-connected but also powered by solar with significant battery storage.

Canadian society is based on importing the things we need rather than producing or manufacturing them ourselves. This puts food—one of the physiological foundations—at risk. It is also learned behaviour which can be quickly reversed, as demonstrated by Kanaka Bar’s approach. Governments can change their focus from growing the economy and GDP to stabilizing them through rural and regional strategic investments in resilient, effective, and efficient growing, processing, storage and delivery food security systems. The goal is that communities can make sure their food is secure, even in the face of extreme weather events.2

Some initial food security planning steps that all orders of governments should undertake together include:

- Economic Leakage: complete a food economic leakage study to determine where our food is coming from, consider want versus need, and assess impacts of extreme weather on supply and costs. Understand what we need to live, and then produce it here!

- Food Sovereignty: support regional food production, processing, and storage through incentives and direct financial support. Create regional food security so that there is always an adequate close source of quality foods so that people never have to go without.

- Land Bank: secure unused arable land from owners who are unable or unwilling to work their land and then lease out at very low rates to farmers or hire workers (local or from other countries) to grow the food we need.

- Food sovereignty, security, and resilience: Rebrand farming and agriculture as a national and province-wide food security issue and promote a resilient food plan. We have the land and resources to generate more than we can eat and thus be in a position to export our surplus but we need to ensure we have the food we need to eat before we put the economy at the forefront.

- Food hubs: Make strategic investments in regional storefront and warehousing of fresh and processed food so a ready supply of food and water is available for residents experiencing an extreme weather event or are in recovery from an event.

Shelter security

The municipality of Lytton lost all its buildings in just over 20 minutes to the fire, and they must rebuild an entire community. The question is will they rebuild it in a way that is resilient to the weather of today and tomorrow.

Nlaka’pamux architecture and engineering for roads, bridges, ditches, boats, energy, and shelter existed for generations before contact as first observed by initial European explorers to the region (Lamb 1960). With colonization and confederation, Nlaka’pamux were required to leave their original places of occupation to live year-round on reserve lands in stick and frame homes built above ground. These homes never met any standards other than the most basic and are not suitable for today’s extreme weather events. Now the Nlaka’pamux, like everyone else, must find a way to design and build shelters that are affordable, resilient (to heat, wind, rain, and cold), energy efficient, and constructable. Kanaka Bar recognized the challenges post-contact policy had on housing, and for years worked to renovate and retrofit deficient existing structures. Today, all new builds in Kanaka Bar are based on passive design and have high-energy efficiency requirements. Kanaka Bar’s own “building code” requirements are that design and construction meet the highest efficiency standards and that owners’ representatives are on site during construction so they can ensure that the work meets community requirements. Kanaka Bar is building durable assets for their children and grandchildren—assets that are resilient to climate change. They are not interested in building assets for flipping later for a capital gain.

In addition, a new subdivision currently under construction called the Crossing Place is grid-connected but will have its own power generation and battery storage, so future residents’ lights, heating, cooling, and air circulation systems will work when the grid goes down. In May of 2022, Kanaka Bar met with new suppliers who shared information on building materials that met the community’s criteria for ensuring new infrastructure would be resilient to extreme weather events (River Voices 2022).

The passage of time has not been easy on Lytton’s displaced residents, but they understand they have a second chance and, with appropriate government support, can build back better. First, the town was built over the Indigenous village of Tl’kemstin and the Lytton fire gave the residents an opportunity to do something that was not done previously—complete archaeological works to locate artifacts and develop mitigation plans for the rebuild which will minimize future impacts on undisturbed sites. Secondly, following a first-of-its-kind report (GHD 2021), each property has been cleaned and owners given a site clearance certificate confirming that the soils were inspected and lands cleared of all historical contamination and any toxins released in the June 30, 2021 fire. A builders’ charrette was held in April 2023 and a building symposium in May 2023 to discuss the best steps forward for rebuilding. The first build has yet to be determined and the community now has the options and must make the choice: to not build back the same structures and systems that were lost or following the example of Kanaka, build back so that new infrastructure will be resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Some steps for all orders of government to consider to ensure shelter is resilient to climate impacts:

- Building bylaws and codes review: Building codes, bylaws, and infrastructure policy must take into consideration the site-specific forecasted weather of tomorrow to be climate resilient. Further, insurance providers should take into consideration accommodating these adjustments so that rebuilds after a disaster are resilient or resistant to fire, heat, wind, rain, and cold.

- Government housing: governments should consider taking back land from owners, corporations, and speculators who are sitting on land “as an investment” to build safe and resilient social housing for vulnerable populations that are more at risk from climate impacts because of a lack of access to appropriate shelter.

- Pilot build: the Fraser Canyon region has abandoned, underutilized lands available for government use and Lytton itself will have multiple shovel ready serviced lots that can be used for builds that showcase different building options, envelopes, and systems that are more resilient to climate impacts.

- Land back: if there is no business case to justify private builds or federal, provincial, or governments are unable or unwilling to acquire or build the homes that are needed, give Indigenous people fee simple lands to develop inclusive, sustainable, and resilient rental housing.

There is still time and hope

For thousands of years, Indigenous communities thrived based on a symbiotic relationship with the land3, and when an Indigenous community thrives, so does a region.

It was the actions of a few that created the conditions we are facing today and it is the actions of all of us today that will determine our collective future.

This will require leadership and there is hope—Indigenous Peoples survived contact and ongoing colonization and today, because of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations and movements like Idle no More putting on public pressure, Canadian governments have moved from avoidance to a position of reconciliation based on new relationships and meaningful collaboration (Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives 2018).

The logic is inescapable that the current pattern of temporary extreme weather spikes of too much heat, wind, rain, or cold will continue in greater frequency, duration, and intensity. Although our governments understand extreme weather risks, the financial cost of delaying, and the urgent need to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change, sometimes actions are not taken quickly enough (Sawyer, Dave, Ness, Ryan, Lee, Caroline, and Miller, Sarah 2022). Canadians can overcome learned and reinforced behaviour through awareness and action—there is no more time for denial, hypocrisy, apathy, and complacency. The Fraser Canyon story and regional recovery and rebuild exemplifies the risk of waiting too long to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

On the ground at Lytton, once the now identified contamination risks are alleviated and the archaeological sites are reclaimed and protected, the rebuilding of the B.C. town lost in a day will proceed—with the right government policies, resources, funding, and perseverance—based on a renewed appreciation for the need to protect the four physiological foundations of life: clean air, water, food, shelter. The rebuild, done properly, should provide the Fraser Canyon residents with safety, affordability, and resiliency that enables them to thrive and maintain a high quality of life, regardless of today or tomorrow’s weather.

Our decision makers need to move away from the now outdated colonial principles and approaches that put the economy above everything and understand that the physiological foundations must be the priority for decision making. This is an opportunity not only for Lytton but for the country and the community of Kanaka Bar shows that it is possible. Climate change transition and adaptation is not a cost, it’s an investment in our collective foundations to ensure that all Canadians can weather the coming storms.

Hope flows from action: Our children and grandchildren are worth it.

References

Albrecht G., Sartore G.M., Connor L., Higginbotham N., Freeman S., Kelly B., Stain H., Tonna A., Pollard G. 2007. “Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change”. Australia’s Psychiatry. 2007;15 Suppl 1:S95-8. DOI: 10.1080/10398560701701288. PMID: 18027145.

BBC News. 2021. “The Canadian Town that Burnt Down in a Day” [Video], YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mgpcVwGsNA (Accessed December 18, 2022).

Berezan, Ron. 2016. Fostering Food Security and Food Sovereignty for Kanaka Bar. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/files/fostering-food-security-published-may-2016.pdf

British Columbia Government News. 2023. “Historic Investment in Food Security Supports British Columbians”. https://news.gov.bc.ca/ministries/agriculture-and-food

Carter, Sarah. 1990. Lost Harvests. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Chambers, K., D. Stanyer, and M. Hocking. 2021. “State of the Fraser River at Kanaka Bar”. Ecofish Research Ltd. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/files/ecofish-2021-07-12-2.pdf

Cohen, Jack D. and Alan Westhaver. 2022. “An examination of the Lytton, British Columbia wildland -urban fire destruction.” https://firesmartbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/An-examination-of-the-Lytton-BC-wildland-urban-fire-destruction.pdf

GHD. 2021. “Summary of Results and Safe Work Considerations: Bulk Material Sampling and Air Monitoring, Lytton Wildfire Response Lytton, British Columbia- Emergency Management British Columbia.”. https://lytton.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Summary-of-Results-and-Safe-Work-Consideration.pdf

Kanaka Bar Indian Band. 2015. Kanaka Bar Indian Band: Land Use Plan. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/files/land-use-plan-march-31-2015-pdf-2.pdf

Kanaka Bar Indian Band. 2018. Kanaka Bar Indian Band: Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/downloads/climate-change-vulnerability-assessment-pdf-2.pdf

Karl, Preuss. 2005. “Review of Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia, by C. Harris”. American Indian Quarterly, 29 (3-4), 709–713. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4138999

Lamb, William Kaye. 1960. “The Letters and Journals of Simon Fraser 1806–1808.” Toronto: Pioneer Books, The MacMillan Company of Canada Limited.

Manuel, George, and Posluns, Michael. 1974. “The Fourth World: An Indian Reality”. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 17.

McLeod, Saul A. 2018. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

McMichael, Anthony J., Alistair Woodward and Cameron Muir. 2017. “Climate Change and the Health of Nations”. Oxford University Press.

Michell, Patrick. 2010. “Memory, Loss and Sorrow…”. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/files/memory-loss-and-sorrow-written-first-in-2010.pdf

Michell, Patrick. 2021. “Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events: Opportunities and Challenges for Sustainability – Kanaka Bar Indian Band and Resiliency” [Presentation]. https://www.kanakabarband.ca/files/climate-change-and-extreme-weather-events.pdf

Olsen, Tyler. 2023. “How the Lytton Rebuilt Went Wrong”. Fraser Valley Current. https://fvcurrent.com/p/lytton-rebuild

Partlow, Josh. 2022. “A Village Destroyed by Fire Vowed to Rebuild the Right Way. Then the Fight Begins”. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/12/15/lytton-fire-canada-climate-change/

Rand, Tom. 2014. Waking the Frog: Solutions for Our Climate Paralysis. Toronto: ECW Press.

River Voices. 2022. “Resilient Housing Solutions – Kanaka Bar Band” [Video], YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4H7fJNeGwCc&t=1s (Accessed March 11, 2023)

River Voices. 2020. “For the Next Thousand Years! Kanaka Bar’s Vision for a Sustainable Future” [Video], YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6md2Ld5lChw (Accessed March 11, 2023).

Sawyer, Dave, Ness, Ryan, Lee, Caroline, and Miller, Sarah. 2022. “Damage Control: Reducing the costs of climate impacts in Canada”. Canadian Climate Institute.https://climateinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Damage-Control_-EN_0927.pdf

Tattrie, Jon. 2020. “British Columbia and Confederation”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/british-columbia-and-confederation

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. 2018. True, Lasting Reconciliation: Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in British Columbia Law, Policy and Practices. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ubcic/pages/3894/attachments/original/1543299014/UBCIC_CCPA-BC_TrueLastingReconciliation_full.pdf?1543299014

United Nations General Assembly. 2007. United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

1 Solastalgia is, “the distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment.”

2 March 2023 announcements by the B.C. and Canadian government show they understand the priority of making investments in food sovereignty and security to keep food on the table regardless of the weather.

3 For the Nlaka’pamux, there is a saying, what you do to the land, you do to yourselves so take care of the land and it will take care of you.