Comparing Canadian and American financial incentives for CCUS in the oil sector

Australia’s Green Bank

Introduction

Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC)—often referred to as the country’s Green Bank—provides financing to areas that help drive greenhouse gas emissions abatement. The bank is particularly focused on filling the investment gap that may limit clean energy deployment, while leveraging additional private sector investment into areas of clean growth. Since its inception over ten years ago, Australia’s Green Bank has committed some A$10.8 billion (C$10 billion) in funding across the country’s economy, targeting the agriculture, energy generation, energy storage, infrastructure, property, transport, and waste management sectors.

The Australian Parliament passed the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act in 2012, committing A$10 billion in initial capital allocation, with the first projects funded the following year. The CEFC aims to generate a positive return on its investments, a model initially criticized by some opponents who could not see how low-carbon activities could be reconciled with profitability. Ten years later, the bank has gained support on both sides of the political aisle, with positive financial results and measurable emissions reductions, while also reporting a private-finance leverage rate of 242 per cent. That means that each dollar of public money invested has been matched with at least A$2.42 from the private sector.

Australia’s Green Bank invests in businesses or projects that develop, commercialize, or use renewable energy, energy efficiency, and low-emissions technologies, or those that help improve related value chains. Lacking a clear definition for low-emissions technologies, the Green Bank’s Board determines, on a case-by-case basis, whether an activity fits the category. Note that given political sensitivities, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act specifically prevents the CEFC from investing in carbon capture and storage or nuclear energy.

The CEFC does not give money away; it does not provide grants. Instead, it provides concessional loans that may include lower-than-market interest rates, longer loan maturity, or longer and more flexible grace periods before the payment of principal and interest is due. The CEFC also provides equity-based financing, taking up partial ownership stakes in businesses, often through commitments to related funds, including several growth infrastructure funds.

By accepting a higher degree of risk for low-carbon projects and enterprises, the CEFC helps to leverage private-sector investment. Beyond acting as a trusted co-financier, the bank’s financial tools include loan guarantees and other forms of credit enhancement, which help private lenders feel more assured of repayment and profit expectations. The CEFC will generally not be the sole funder of a clean energy investment, and will usually require co-financiers and/or equity partners.

The CEFC’s investment decisions are made independently of government, although an investment mandate provides general direction and is updated periodically. After initial screening to ensure a project or business will accelerate climate change mitigation, an executive committee makes recommendations to the Board based on commercial rigour and ability to provide a positive return on investment.

Description of the policy

Endowment

The CEFC invests on behalf of the Australian government and has maintained its lending structure through its initial A$10 billion endowment and return on investment to date. Specifically, the organization was granted A$2 billion each year from 2013 to 2017 as mandated within the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act. The Act ensures that the government maintains control of that endowment to a certain extent, specifying that the authorized Minister has the right to ask for partial or total repayments to the public purse when or if the CEFC’s special account reaches a A$20 billion surplus.

Recently, the CEFC was awarded the first injection of new capital since 2017. The government committed in the October 2022 federal budget to an additional A$8.6 billion for the CEFC to use towards its Rewiring the Nation policy objectives. Rewiring the Nation aims to enable renewable energy transmission across national energy markets, and the CEFC’s role will be to invest in priority grid-related projects. Expanding clean electricity generation is seen as fundamental to reaching Australia’s legislated targets of reducing emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, and reaching net zero by mid-century.

Meanwhile, in November 2022 the government committed a further A$500 million to the CEFC for the “Powering Australia Technology Fund,” to support the commercialization of innovative new technologies, such as energy-efficient smart city sensors and innovations in solar arrays and battery technologies. The top-up was made possible through an amendment to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act as part of a treasury bill amendment process.

Oversight

The 2012 Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act established the CEFC and set out the organization’s purpose, functions, and staffing arrangements, while the Australian Government Investment Mandate provides directions to the independent CEFC Board and is updated regularly. The CEFC Board is responsible for final investment decisions, and is made up of seven board members appointed by the government for renewable five-year terms. A Chief Executive Officer is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the corporation.

The investment mandate provides updated direction on the targeted allocation of investments among the various classes of clean energy technologies, concessional term expectations, the types of financial instruments in which the corporation may invest, and the nature of any financial guarantees given.

The Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act itself mandates transparency requirements, such as publishing quarterly reports on investments made, including their value, timeline, project location, and expected rate of return, as well as an annual report with total investments made and estimated value of concessions provided.

Financial pathways and mechanisms

Depending on the size of the request and nature of the project, the Green Bank’s financial support can take different forms. These include direct investments, investments in specialized funds, and the specialist asset finance program.

The CEFC’s direct investments into large-scale projects and funds average A$20 million, but can range from A$5 million to an uncapped amount, and cover some 265 transactions to date. Technologies under this category must be ready for commercialization, meaning they have passed beyond the research and development stage and have identified a clear path to market. This includes the potential for both domestic and global market application of the technologies.

Related instruments for large-scale direct investment include flexible debt or equity finance, or a combination of both, tailored to individual projects. For example, the CEFC invested A$5 million in the 300-megawatt Blind Creek Solar and Battery Project. The agreement saw a joint venture established between the CEFC and Octopus Investments Australia, one of the world’s largest investors in clean energy.

Meanwhile, financing for smaller-scale or agribusiness projects is provided via asset finance programs delivered through co-financiers, such as major banks or specialized lenders. Project proponents must go directly to these co-financiers to apply for funding. The CEFC provides finance for these smaller-scale projects in the range of A$10,000 to A$5 million, but the co-financiers must also invest and must administer the financing for the project.

These small-scale transactions are administered under the CEFC’s Specialist Asset Finance Program, which is designed to extend the reach of the bank’s finance to tens of thousands of small-scale investors without having to increase the size of the CEFC’s in-house operations or staff. Eligible projects range from small-scale rooftop solar and battery storage, to energy efficient manufacturing and farm equipment, to improved building insulation, heating and cooling, demand management systems, and zero emissions vehicles.

Recognizing the unique nature of innovative technologies, the CEFC created the Clean Energy Innovation Fund in 2015. Technologies accessing this funding do not need to be ready for commercialization, with targeted support available at the earliest stages of development.

This support is provided through three cleantech accelerator and incubator programs—Artesian, Tenacious Ventures, and Startmate. Beyond financing, these programs provide other forms of support to help guide young companies through the first few turbulent years, and also work to match these companies with domestic and international cleantech investors.

To date, around 80 cleantech companies have received funding through the Innovation Fund, with related investment totalling A$18.3 million. This includes some debt, but mostly equity investment in emerging clean technology projects and businesses, recognising the unique characteristics of budding cleantech companies, and delivering a financial return at the later end of the innovation chain. Early-stage investment company Virescent Ventures manages the Clean Energy Innovation Fund on behalf of the CEFC, while the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) is a co-manager of the fund.

Other CEFC programs to note include the first green home loans, which launched in 2020 in partnership with Bank Australia, and the first hydrogen sector investments in 2021. Committed investments into the hydrogen sector currently amount to A$23 million across three transactions. The CEFC is also a leading investor in Australia’s emerging green bonds market, creating new options for investors, issuers, and developers. The CEFC also leverages private investment by pooling loans into portfolios, a type of securitization that allows investors to reduce their risk by spreading investments across a range of clean energy projects.

Policy strengths and limitations

Strengths

1. The Green Bank generates a positive return on investment.

In its first decade, the CEFC made low-carbon investment commitments of A$10.76 billion, from its initial A$10 billion endowment. As of June 2022, the CEFC reported that it had access to A$4.57 billion in investment capital, in addition to ongoing returns from investment. These figures demonstrate a significant return on investment to date, with additional and ongoing investments expected to see the overall size of CEFC’s assets continue to grow.

2. The Green Bank is achieving significant emissions reductions.

As of June 2022, the CEFC estimated its lifetime emissions reductions from existing investment commitments at more than 200 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. This includes more than A$3 billion in renewable energy investment, with the resulting projects generating more than 5 gigawatts of solar and wind energy. New investments in the manufacturing sector could soon boost the total figure by 0.9 megatonnes of carbon abatement annually.

3. The Green Bank has successfully crowded-in private sector investment.

Green banks encourage investors to back low-carbon technologies or projects that may be perceived as risky, often by assuming a portion of that risk themselves. Australia’s Green Bank also attracts co-financiers into emerging or unproven areas, convincing private investors to follow its lead. This type of “crowding-in” activity has leveraged investments of over A$37.15 billion for low-carbon projects from the initial A$10 billion endowment, according to CEFC estimates that factor in the additional investments leveraged from third-party private finance.

4. The Green Bank has successfully avoided crowding-out private-sector investment.

The CEFC is mandated to balance its objectives to deliver emissions reductions and profitability, with the imperative of ensuring that it does not provide financing where the private sector otherwise would. The CEFC says this means retreating where the private sector is operating effectively, and stepping up investment activity to fill market gaps where the private sector is absent. In practice, this means analyzing each transaction to ensure that there is really a need for the CEFC’s intervention. As a result of this policy, the bank may be less active in years of market strength, where there is a lot of private-sector certainty and investment, and more active in years with market instability.

Limitations

1. There is some potential for the Green Bank to be vulnerable to political interference.

While the CEFC acts independently of government, its Board is appointed by the ruling government and the CEFC must follow the government’s investment mandate. This allows the ruling government to provide instructions on the types of investments the CEFC should pursue, as well as restrict or otherwise change the design of financial instruments, providing a degree of regulatory uncertainty to the private sector. For example, the 2020 Investment Mandate, submitted by the Liberal/National Coalition government, sought to limit the amount of public support provided to low-carbon areas. This included limits on concessionality in any one financial year to A$300 million, essentially steering the CEFC towards more commercially attractive terms and market rates. At the same time, the government limited the use of financial guarantees, noting that the CEFC should seek to avoid their use given that “guarantees pose a particular risk to the Commonwealth’s balance sheet.” The current Labor party government, led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese since the May 2022 election, has reversed these references while also amending the Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act itself to include a specific mention to emissions abatement (in addition to the existing “clean energy” wording).

2. The Green Bank does not target or measure outcomes related to equity or climate justice.

The CEFC has limited commitments related to social or environmental justice and equity. While there is a strict policy of screening investment proposals to mitigate negative impacts on Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders, for example, there is limited concrete effort to direct investment towards positive outcomes for these groups, despite the CEFC’s Reconciliation Action Plan including a promise to examine the issue. This is in contrast to other green banks, or similarly structured funds, that have specifically made equity considerations a key metric to be included in lending decisions. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, for example, created the US$27 billion federal Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund to help finance clean energy and climate projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions—and specifically earmarked more than half of that amount, US$15 billion, for projects in low-income and disadvantaged communities, aiming to accelerate climate justice in these regions.

Lessons for Canada

Canada has at least two existing initiatives at the federal level that aim to mirror many of the functions of Australia’s CEFC. These include the Canada Infrastructure Bank and the new Canada Growth Fund. The Canada Infrastructure Bank operates similarly to Australia’s Green Bank, as an arm’s length corporation. While the Canada Infrastructure Bank is not specifically mandated to accelerate the low-carbon transition, two of its five priority areas relate to climate change—green infrastructure and clean power—with a key objective to reduce climate pollution over the lifecycle of the activities. Many of the Canada Infrastructure Bank’s financial mechanisms are similar in structure to CEFC, aiming to leverage private capital, including through debt products targeted at private-sector market participants. Noteworthy “green” endowments include C$2.5 billion for clean power, C$2 billion to invest in large-scale building retrofits, and C$1.5 billion to accelerate the adoption of zero emission buses and charging infrastructure.

In addition to the Canada Infrastructure Bank, the new Canada Growth Fund plans to spend C$15 billion over three years, modelled broadly from green bank principles. The fund, first announced in the April 2022 budget, will make concessional investments to spur clean growth. It is prepared to shoulder investment risk to leverage private sector capital, and is prepared to accept a lower return and greater risk than traditional banks or financial institutions.

Three major lessons can be drawn from the 10-year history of Australia’s Green Bank that can help the Canada Infrastructure Bank and the Canada Growth Fund define or improve their principles and approach:

1. Define, and stick to, an umbrella mandate and principles.

For green banks and green funds to be successful, investments must be mission-driven, having a specific objective beyond financial returns, and clear guiding principles to ensure efficiency. In contrast, the broad-based nature of the Canada Infrastructure Bank mandate has meant that it is not always clear how low-carbon projects may or may not be favoured over traditional endeavours, and how the myriad programs fit together towards common objectives.

Meanwhile, the Canada Growth Fund must continually underpin every decision with its overarching principle of helping Canada reach net zero emissions by 2050, while complementing this objective with climate justice and reconciliation objectives. This means focusing on deploying well-established technologies such as renewable energy and energy efficiency, but also ensuring that new innovations are nurtured through targeted initiatives—as Australia has done with its Clean Energy Innovation Fund. It will also be important to develop a strategy that will guide the prioritization of projects, something that could, for example, be performed through modelling viable low-carbon transition scenarios, and identifying areas with comparative advantages for global markets.

The Canada Growth Fund must also ensure that it is not crowding-out private sector investment, and make this a key pillar to its mandate. Lessons can also be learned from the United Kingdom in this regard, which sold off its Green Investment Bank in 2017 after only five years, with many blaming the retreat on the bank losing sight of this element within its mandate. That is, the bank faced criticism that it stuck around in sectors after they had matured, directly competing with private investors.

Finally, these investment principles should be turned into impact metrics, or key performance indicators, in order to track and report results over time. Australia’s quarterly reports and annual summaries provide data related to funding, but also key metrics related to emissions abatement, renewable energy additions, concessional spending, and proportion of leveraged private-sector investment.

2. Identify and target the most strategic private partners.

Some of Canada’s largest institutional investors have increasingly opted to invest in projects outside of Canada. Canada’s biggest eight pension funds, for example, collectively manage over C$2 trillion in assets, but are largely invested abroad. Canada should ensure that the Canada Infrastructure Bank and Canada Growth Fund target co-financing arrangements with these types of key organizations, recognizing the supersized financial strength such partnerships can leverage.

A significant part of CEFC staff’s objectives involves establishing and nurturing strategic relationships. This includes working closely with strategic private partners on financing smaller-scale projects and working with banks and co-financiers to deliver discounted finance. Canada can learn from this experience, and instead of trying to reach smaller-scale project proponents directly, can lean on the established networks of partnering banks and specialized lenders. This will avoid many administrative and transactional costs and is likely to ultimately be a more efficient use of public funds. In this regard, it will be important to bolster partnerships with end-user support programs, for example by ensuring participating banks have dedicated asset finance channels to assist customers with eligibility and loan applications.

3. Make developing institutional knowledge and relevant expertise a top priority.

Institutional knowledge and human capital are critically important to the success of green banks and green investment funds. It is crucial to hire staff with technical knowledge related to both finance and the low-carbon transition. This will be key to assessing the viability and political impact of projects, including identifying the ultimate sources of income for low-carbon energy and technologies; as well as policy levers that are already helping to spur investment in those areas, such as carbon pricing. While consultants can be used to perform some key tasks, personnel should, at a minimum, be effective at public communication and developing partnerships. Australia’s CEFC is a small organization with a broad reach, and therefore often relies on the skillset and technical capabilities of its partners, making these attributes a key consideration when selecting co-financiers and/or investable projects.

Conclusion

Australia’s CEFC offers ten years of experience with investments into low-carbon projects, businesses, and technologies. It has expanded its focus from renewable energy generation to low-carbon innovations, and more recently to infrastructure to support electrification such as smart grids. All of these climate change solutions require funding, something that the CEFC is willing to offer at more generous and flexible rates than private-sector investors. The CEFC has learned to be cautious about crowding-out private-sector investment, avoiding any transaction where private actors are already filling the gap. Instead, it aims to accelerate its operations in times of uncertainty, embracing risks related to the clean energy transition. In so doing, it has a proven track record of its financed projects resulting in measurable greenhouse gas abatement, leveraging considerable sums of private-sector finance, and demonstrating a positive return on investment. Canada can learn from this model as it implements its new Canada Growth Fund and the Canada Infrastructure Bank continues to evolve. Primary lessons learned that may shape the Canadian context include articulating and following investment principles, building relationships with strategic private-sector partners, and fostering the types of knowledge and transparency that will grow the clean economy investment landscape.

The United Kingdom’s contracts for difference policy for renewable electricity generation

Introduction

The United Kingdom’s Contracts for Difference (CfD) is a publicly funded support measure for large-scale renewable energy projects, introduced in 2014. The CfD policy targets clean electricity investment—to date, mainly offshore wind—and is designed to protect project proponents from changes to the wholesale electricity price.

Canada, through its new Growth Fund, has recognized CfD policies as an effective way to provide the private sector with price or revenue certainty. Canada has also considered ways to better guarantee its carbon price schedule through carbon contracts for difference (CCfD), a policy that would be similar to the UK’s CfD but offers certainty around the price of carbon, rather than the price of electricity.

In effect, the U.K. CfD policy closes the gap between the price that a clean electricity generator needs to receive in order for the business investment to be attractive, and the price provided through supply-and-demand dynamics on the fluctuating power market. The CfD therefore provides a guarantee of a steady revenue stream, addressing private-sector investment risk and making for a more appealing investment environment compared to other forms of energy.

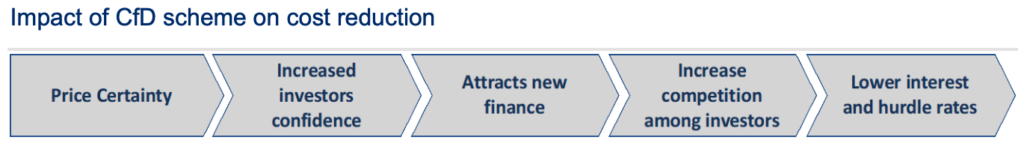

The certainty provided by the CfD also allows project developers to borrow money at lower interest rates, attracting new entrants that increase competition and help drive down costs. This attractive investment landscape, coupled with technology advancements and economies of scale, has seen the public cost of the U.K.’s CfD on a per-kilowatt basis fall significantly over the years.

Figure 1: The U.K.’s CfD reduces costs to the public by providing price certainty to the private sector.

As a subsidy-based policy, the U.K.’s CfD has a unique financing structure in that it is ultimately paid for by U.K. power consumers—though one of its longer-term objectives is to stabilize consumer electricity rates. The CfD payments are funded by a statutory levy on all licensed electricity suppliers, with this cost eventually passed on to households and businesses through their power bills.

The private market intervention has been justified by policymakers through three channels: greenhouse gas emissions reductions, energy security, and long-term energy affordability. On the first, the U.K. is striving towards a mid-century net zero greenhouse gas emissions target, pledging to decarbonize the electricity grid by 2035 from the current over-40-per-cent fossil fuel-based portfolio.

Meanwhile, Europe’s current energy crisis has brought energy security and affordability to the forefront of policy decision making. While some observers have called for quick-fix fossil-fuel production increases, successive heads of U.K. government have noted that renewable energy will ensure less exposure to volatile fossil fuel prices set by international markets.

The U.K.’s independent Climate Change Committee, the official advisor to the government, has estimated that reaching the net zero commitment will require an investment of £50 billion (C$81 billion) a year by 2030, with much of this investment needed to replace older energy-related infrastructure. The U.K. government has said that it aims to leverage £90 billion (C$146 billion) of this amount from private actors through 2030.

With these objectives clearly defined, the U.K. government hit the accelerator on the CfD policy in February 2022, committing to annual auctions from March 2023 rather than the previous biennial schedule, with the aim of more rapidly spurring private capital towards quicker renewable energy deployment.

Description of the policy

All power generators sell their electricity on the open market in the U.K., or sometimes through a power purchase agreement. The market price fluctuates with supply-and-demand dynamics, where the price received is determined by the cost of supplying the last unit of electricity. In the U.K., it is the marginal cost of fossil gas-powered generation that currently sets the wholesale price across the market. Since the price of fossil gas is determined on the international market, power prices can vary significantly, and are currently very high due to the region’s geopolitical instability.

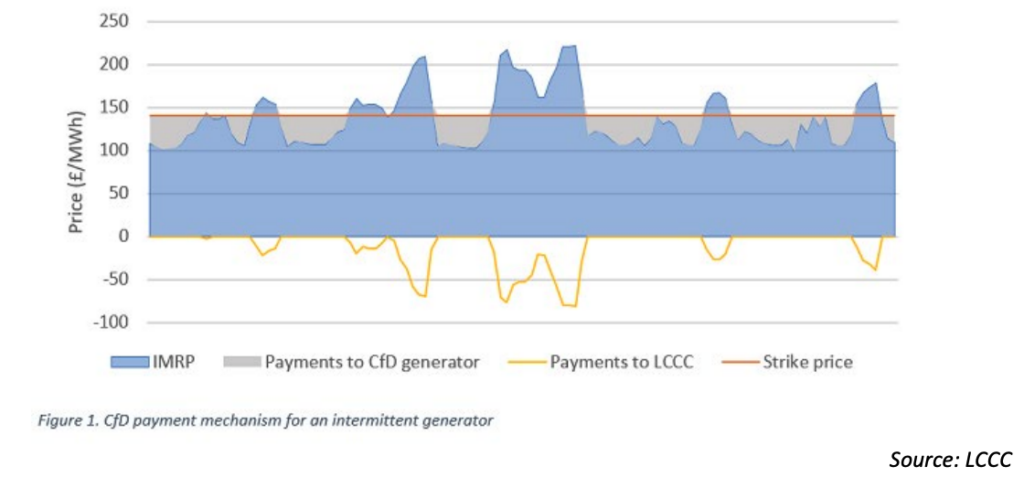

The CfD is designed to fill the gap between this wholesale market price and the generator’s strike price. The strike price is determined through the auction process and, once set, will not fluctuate throughout the life of the contract, currently 15 years. Generators will consistently receive the strike price for each unit of electricity produced.

Within the auction process, renewable generators submit a sealed bid that represents the price they desire to be paid per kilowatt hour to make the project profitable. An administrative maximum strike price is set by the U.K.’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the entity responsible for the policy. The U.K.’s system operator, the National Grid, runs the auctions and ranks the bids by unit price. It then accepts the best bids up to the point where the budget or capacity caps are reached. The sealed bid for the last project accepted sets the strike price that all successful bidders receive, so long as they are in the same year/technology “pot.” While the strike price applies to the full 15 years of the contract, it is indexed for inflation, with annual adjustments.

While the policy is run by the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy department, the contracts themselves are administered by the Low Carbon Contracts Company, a government-owned private company. The Low Carbon Contracts Company is also tasked with recouping the cost of the program through a levy set on power suppliers—that is, those delivering final electricity requirements to end-use consumers.

An important design detail for the CfD is that payments are run on a two-way street. If the average wholesale price (the “reference price”) is below the strike price, the Low Carbon Contracts Company pays the generator the difference. But when the strike price is below the reference price, the generator pays the Low Carbon Contracts Company the difference (Figure 2).

Up until recently, the reference price had been consistently below the strike price of projects, and the Low Carbon Contracts Company had been directing difference payments to generators. However, with the onset of the European Union’s energy crisis and related sky-high fossil gas prices, the wholesale electricity price has been above the strike price, meaning that generators have made payments back to the Low Carbon Contracts Company.

Figure 2: Under a two-way CfD, firms make or receive support payments depending on market price

The CfD continues to garner considerable interest from the private sector, with investment pouring into the market. Results from the policy’s fourth allocation round were published in July 2022, confirming 93 new projects, more than in the previous three auctions combined, and bringing the total number of CfDs under management to 168. The allocation round is expected to result in nearly 11 gigawatts of additional generating capacity, with these sourced from offshore wind, onshore wind, solar, remote island wind, and—for the first time ever—tidal stream and floating offshore wind. When those projects are all in operation, CfD-combined projects will provide around 30 per cent of the U.K.’s power needs. The fifth allocation round that is due to open for bids in March 2023 will push this figure upwards.

Policy strengths and limitations

As a result of the significant additions to renewable energy capacity to date, and innovative auction-based design, the U.K. CfD is broadly recognized as a policy success story. The policy has several strengths relative to its predecessor, the Renewables Obligation system, which placed a requirement on suppliers to source an increasing proportion of electricity from renewable sources, similar to a renewable portfolio standard. Since the Renewables Obligation system could have achieved the same renewable capacity result as the CfD, it is worth considering the specific characteristics that have made the U.K.’s CfD policy world-renowned, while it is also important to note its limitations.

Strengths

- The U.K.’s CfD policy is designed to offer price certainty while remaining cost efficient, minimizing pressure on the public purse.

Subsidy-based programs are often criticized for inefficiencies, including when publicly funded payments are higher than what would be required to spur private action, resulting in freeriding. Freeriding can be a problem because incremental public payments do not result in incremental investment. The policy has weakened these types of occurrences through the competitive nature of its auctions, which have been able to leverage competition and capture the falling costs of renewable technologies.

Reflecting the falling costs of renewable technologies, costs per kilowatt hour have fallen successively each CfD round, and by a massive 65-75 per cent since the first auctions were held in 2015.

As only the lowest price bids are successful, private actors will compete against each other, finding innovative ways to drive down costs, and ultimately bringing down the cost of the policy on ratepayers.

- The two-way nature of the policy means that payments can either be received or made, limiting the risk of publicly funded windfall profits.

The two-way design characteristic, which sees generators pay into the program when the wholesale price of electricity is high, has been particularly important for cost efficiency as well as for garnering public support. Since September 2021, record-breaking energy prices have seen low-carbon generators under the CfD scheme make payments back that reflect revenues received in excess of the agreed strike price. Since the design of the CfD largely prevents participants from reaping windfall profits at times of high wholesale energy prices, they have been exempted from the 45 per cent windfall profit tax that the U.K. will levy on other energy providers between January 2023 and March 2028. This has also meant cost savings for ratepayers, with over £1 billion (C$1.66 billion) in revenues from generator payments expected to be received between April 2022 and March 2023.

- The program is administered at arm’s length from government, decreasing political risk.

Ensuring the CfD is administered through a private organization protects the integrity of the program from political fluctuations. Successful renewable project proponents enter into a private law contract with the Low Carbon Contracts Company, which issues the contracts, manages them during the construction and delivery phases, and issues CfD payments. The government is the sole shareholder of the Low Carbon Contracts Company and therefore is represented on the board, and requires certain types of reporting to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. But the CfD is designed as a private-law contract, in which the Low Carbon Contracts Company is the counterparty, and cannot be cancelled without legal repercussions. This protects the policy from political interference or cancellation, promoting investor confidence.

Limitations

- The policy is regressive, meaning that it has a worse impact on lower-income households’ spending power.

Given that the CfD policy is paid for through a per-unit levy on end users, the more electricity consumed, the higher one’s payments towards the scheme. Although the amount of power consumed normally increases with income—making overall payments to the program larger for higher-income earners—lower-income earners generally pay a higher proportion of their available income towards energy costs, making the policy regressive. For this reason, complementary policies are advisable to lessen the disproportionate burden of the levy on lower-income earners. The U.K.’s Warm Home Discount Scheme, fuel vouchers, and Cold Weather Payments are all examples of complementary policies offering this type of targeted support.

- The policy takes time to demonstrate measurable results, both in terms of new renewable capacity additions, and resulting emissions cuts.

Although all policies take time to show results, the U.K. experience clearly demonstrates the delay between policy implementation and the time it takes for renewable power objectives to materialize. Contracts awarded in October 2019 will see committed capacity come fully online only by 2027, though there will be a gradual ramp-up to this capacity onwards from 2024. Private-sector industrial investment decisions can take years to develop, and the price certainty offered by the CfD is needed before most projects can access capital and begin due diligence and other approval processes. Measurable emissions reductions follow many years later.

- The CfD’s payback structure includes administrative inefficiencies.

Since September 2021, wholesale power prices have exceeded CfD strike prices, requiring generators to make payments back to the Low Carbon Contracts Company. This has meant that the levy on suppliers has been set to zero because the regulations do not allow the Low Carbon Contracts Company to set a negative levy rate. Instead, the reverse flows happen at quarterly reconciliation points where the Low Carbon Contracts Company pays the accumulated sum of the payments to suppliers. The challenge is that these quarterly payments are not translated in the same way into reduced payments for consumers. It is left to suppliers to determine how the Low Carbon Contracts Company payments are used, and it is not clear to what extent the payments help mitigate higher power bills. That is the cost-saving pass-through rate is not always known.

Lessons for Canada

Generally speaking, CfD policy can be applied to other climate change mitigation technologies under consideration in Canada, such as carbon capture and storage and clean hydrogen production. There are, therefore, several applicable lessons from the CfD policy that may be beneficial to Canadian policy development, particularly as Canada examines the CfD financial model to support industrial decarbonization, including under its new Canada Growth Fund.

- Provide price or revenue certainty to help address financial risk, to foster long-term investment.

CfD is able to spur private investment through risk management, including by providing certainty about a project’s revenues. The U.K.’s CfD policy also pushes the administration of the contracts to a private company, the Low Carbon Contracts Company, sheltering the policy from inconsistencies in political support and risks of program rollback. The Low Carbon Contracts Company could serve as an important model for administering Canada’s $15 billion Growth Fund. The fund—slated to be launched by the end of this year—has promised to include a “permanent and independent” structure, which is to be defined by the first half of 2023. Although further details are not yet known, the government has been clear that the growth fund will transition from a subsidiary under the Canada Development Investment Corporation to an institution with operational independence.

- Help private investors tackle the cost of borrowing to bring down overall project costs, lessening he level of subsidy required to incentivize project development.

The cost of capital can be a significant portion of project costs and an indicator of whether a project will go ahead, with these costs generally increasing with the risk profile of the project. The certainty provided by the CfD makes a project more attractive to investors, lowering interest rates and thereby overall project costs for project developers. Beyond assurance of a solid and long-lasting program, this requires sophistication in lending institutions, and government programs could be developed to ensure capacity to correctly identify the risk mitigation effects of the policy.

- Target mature and established technologies when using the U.K.’s CfD structure.

The CfD policy was applied in the U.K. after renewable power, specifically offshore wind, was well advanced. To get to that point, government policies focused earlier on research-and-development investment and supply chain growth. CfD policies may be more suitable to scale technologies that have already proven themselves, rather than early-stage innovations.

- Require multiple bidders within each auction to establish healthy competition.

As a result of its auction-based design, the U.K.’s CfD has been successful in driving down costs compared to other forms of subsidies. Private actors are incentivized to find cheaper ways to generate clean electricity in order to win the contracts, driving down costs. However, in order for auctions to be successful, there needs to be many private actors involved, and these actors should not have means to collude on price bids. A strong pipeline of projects and cohort of developers is needed for the auction model to be successful.

- Consider made-in-Canada supply chains and labour enhancements to help boost broader competitiveness objectives.

The low-carbon transition is set to present a significant economic opportunity, but global competition is likely to be intense. Many countries are taking a strategic approach to their industry support policies. The U.K. has recently made locally sourced content requirements a part of CfD eligibility for turbines, something that Canada might consider when examining supply-chain requirements. Other related provisions include building domestic talent through employment strategies that are tied to the policy’s support structure.

Conclusions

The U.K.’s CfD has proven to be a policy success story, spurring additional renewable capacity, leveraging private-sector investment, and both driving and benefiting from falling technology costs. The transferability of this success to the Canadian context, however, will depend on several factors. Primarily, the U.K. CfD model is best suited to mature technologies with robust market competition, to ensure successful auctions. The price guarantee must then be delivered over a long-time horizon, such as 15 years, with a suitable administrative institution that is not vulnerable to political fluctuations.

Hydrogen tax credits in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act

Introduction

The United States passed the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022—landmark legislation that earmarked around $369 billion for energy security and climate change initiatives, including an unprecedented focus on clean hydrogen. The act introduced a clean hydrogen production tax credit and extended the existing investment tax credit to hydrogen projects and standalone hydrogen storage technology.

Tax credits have been broadly applied globally. They have the potential to mobilize private-sector capital into desired areas, essentially subsidizing a portion of the cost of goods or behaviours, and incentivizing their adoption. Here in Canada, examples of tax credits range from charitable donations by individuals to scientific research by businesses. Though the term tax credit can often be confused with a deduction in taxable income, refundable tax credits represent a direct payment, and like all subsidies, they are financed through the public purse.

Tax credits can make clean hydrogen production more attractive than alternatives, lowering investment costs or increasing return on investment. Tax credits can also be applied to strengthen hydrogen demand by subsidizing end-use applications such as heavy-duty hydrogen-powered vehicles.

This case study will examine a range of private and public policy implications from using tax credits, both domestically and internationally, including their impact on global competitiveness. The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act south of the border has led Canadian businesses to call for additional government support, arguing that projects and capital will flow to the jurisdiction offering the greatest economic advantage.

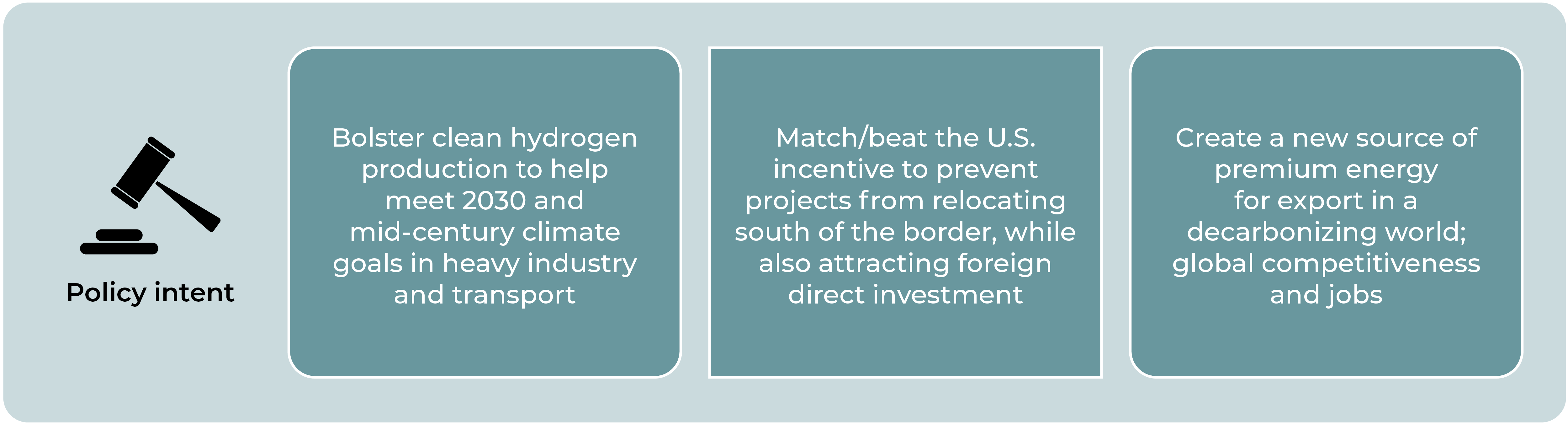

In the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, the Canadian government reconfirmed its Budget 2022 commitment to establish a clean hydrogen investment tax credit. The credit is set at a maximum of 40 per cent of project costs—an increase from the 30 per cent proposed in the previous spring budget—based on climate impacts and labour conditions. The intended policy outcome of the Canadian investment tax credit is likely to be threefold, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Canada’s proposed hydrogen tax credits can achieve three policy aims

This case study takes a closer look at the U.S. hydrogen tax credits, and explores how their design may inform Canada’s support for hydrogen fuels in particular as well as its use of tax credit policy more broadly.

Description of the policy

The Inflation Reduction Act tax credits are available for clean hydrogen projects, where “clean” is defined as producing less than 4 kilograms (kg) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per kilogram of hydrogen, measured on a life-cycle basis. For comparison purposes, emissions associated with “grey” hydrogen—the most common form of U.S. hydrogen production, produced with natural gas—range from around 10 to 12 kg of CO2e per kilogram.

The process-neutral design of the credits allows for many different types of technologies to be eligible, including electrolysis from renewable electricity to create “green” hydrogen, or steam methane reforming with carbon capture to create “blue” hydrogen, as both of their emissions intensities may be lower than the 4 kg cap.

The Inflation Reduction Act package included both an investment tax credit as well as a production tax credit, and will also support other parts of the hydrogen landscape through tax credits for clean energy and energy storage, as well as credits for fuel cell vehicles and alternative-fuel refuelling infrastructure.

Investment tax credit

The Inflation Reduction Act allows clean hydrogen production facilities to be included in the scope of the investment tax credit program for clean energy (Section 48 of the Act). Clean hydrogen project proponents may receive support equal to up to 30 per cent of their project costs, depending on the emissions intensity of their production process. A facility will receive a proportion of the maximum investment tax credit for the year that it is placed into service, depending on its emissions intensity, and wage and apprenticeship requirements. The amount of the credit is multiplied by five if certain wage and apprenticeship requirements are met.

Table 1: Lifecycle (“well to gate”) emissions, and share of project costs eligible for credit

| Kg CO2e per kg of clean hydrogen | Portion of project costs claimable as credit | Tax credit with wage and apprenticeship conditions |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5-4 | 1.2% | 6% of project costs |

| 1.5-2.5 | 1.5% | 7.5% of project costs |

| 0.45-1.5 | 2% | 10% of project costs |

| 0-0.45 | 6% | 30% of project costs |

The investment tax credit can also help companies access upfront capital, addressing a major barrier to project development, as banks and other investors will build the investment tax credit into lending decisions. Under the Act, hydrogen-related credits are also eligible for transfer to unrelated persons in a non-taxable cash sale.

Production tax credit

The Inflation Reduction Act’s new production tax credit—under section 45V of the Act—provides a payment over a 10-year period based on the amount of hydrogen produced. The value of the production tax credit varies depending on the clean hydrogen’s lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions intensity, with producers receiving a maximum of $3.00 per kg of hydrogen for the least emissions-intensive product, down to $0.60 per kg of hydrogen for the most emissions-intensive. The amounts depicted in Table 2 assume all wage and apprenticeship criteria have been met.

Table 2: Lifecycle (“well to gate”) emissions rate and resulting percentage eligible for credit

| Kg CO2e per kg of clean hydrogen | Portion of maximum tax credit | Tax credit |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5-4 | 20% | US$0.60/kilogram |

| 1.2-2.5 | 25% | US$0.75/kilogram |

| 0.45-1.5 | 33.4% | US$1.00/kilogram |

| 0-0.45 | 100% | US$3.00/kilogram |

Strengths and limitations of the policy

It is too early to say whether the U.S. tax credits will be successful in driving clean hydrogen production over more carbon-intensive methods. For this reason, this policy brief draws strengths and limitations of tax credit policy from broad-based economic theory, coupled with the U.S. experience with production tax credits for renewable energy more broadly. Production tax credits for renewables have been used successfully in the U.S. since they were first introduced under the Energy Policy Act of 1992. The production tax credit rate is currently 2.75 cents per kWh for wind, solar, geothermal, and closed-loop biomass power plants.

Strengths

- The tax credits are designed to spur private investment.

Tax credits lower the private costs of project development or operation, making these endeavours more financially attractive, and spurring interest from both domestic and foreign capital providers. Realizing the energy transition requires redirecting private-sector investment into areas of clean growth while attracting new sources of foreign investment that can supercharge economic growth more broadly.

- The policy will help grow the clean hydrogen industry and drive down prices.

New investment and private-sector interest can help the clean hydrogen industry scale, creating efficiencies and improvements that drive down prices. In the U.S., the cost of solar and wind generation has fallen dramatically as the industry has grown, with tax credits one of the drivers of economies of scale and efficiencies created through learning curves or experience curves. As a result of these realized efficiencies, both solar and wind are increasingly cost-competitive with dirtier forms of electricity generation, when measured across the lifecycle of the project.

- The policy allows cleaner forms of hydrogen production to compete with dirtier alternatives.

In the absence of subsidies, private actors will choose the cheapest way to produce and deliver hydrogen, and in the case of hydrogen production in the U.S., this is usually fossil gas. The clean hydrogen tax credits are designed to redirect the market to cleaner forms of production. Investment tax credits encourage private actors to take on investment risk for clean hydrogen projects, while production tax credits provide an additional return on investment beyond market prices. This allows clean hydrogen to compete with dirtier alternatives, bolstering a clean fuel needed for deep decarbonization, and attracting growth and jobs into the clean-energy industry.

- The tax credits support an industry that may have significant export potential

Hydrogen provides a global export opportunity, where clean hydrogen-based fuel is expected to be in high-demand in a decarbonizing world. Preparing domestic industries to meet this demand is smart, forward-looking industrial strategy. It prepares domestic industry for the global energy transition ahead, and helps provide additional supply of a clean fuel that is needed to tackle the climate crisis.

- The policy layers on a requirement for robust labour conditions, helping to ensure public support and social objectives.

The U.S. couples its clean-hydrogen tax-credit eligibility requirements with wage and apprenticeship criteria, allowing the stimulus to create good jobs and skill development. These rules include paying specific workers a prevailing wage and employing a certain number of registered apprentices. This provision helps ensure social equity objectives by promoting higher local standards for pay, training, and job quality. It also helps ensure ongoing public support for the policy since both the business and its workers can see direct benefits.

Limitations

- The policy draws on a finite public budget.

Subsidy-based policies fund private-sector activity through public dollars, where there is an opportunity cost to those dollars, such as foregone health care expenditures. Expenditures may be pitted publicly against shorter term needs. In addition, governments making a big bet on a technology can be risky, in terms of whether it will be able to scale, compete globally, or fully deliver a low-carbon climate solution. In addition, while the point of tax credits is to spur greater uptake, the cost of the policy will rise as deployment/use increases. As a result, capping or limiting the overall expenditure (or foregone revenue) of the tax credit policy may be needed to ensure accurate budget foresight.

- Public spending through tax credits can result in perceived or real inflationary pressures.

Canada’s inflation rate was 6.8 per cent in November 2022, down from the 39-year high of 8.1 per cent in June 2022, but far above the Bank of Canada’s 1-3 per cent target. This macroeconomic context means policy interventions must be designed carefully. Additional government spending can be inflationary, or can be perceived to be inflationary. Significant political opposition, citing concerns of inflation, forced the U.S. to ensure that the Inflation Reduction Act was fully funded—something made possible through spending cuts in other areas, but mostly through implementing targeted tax increases on highly profitable corporations. Of course, government spending can be non-inflationary if it bolsters productivity or relieves supply constraints in energy and labour markets, conditions that need careful consideration in tax credit policy design.

- Designing effective tax credits requires technical knowledge about the industry and reliance on uncertain cost projections.

Technical insight is required in order to choose the right levels of subsidy support and eligibility requirements: a tax credit that is too generous is susceptible to free-riding, where investors would have been willing to make the investment at a much lower incentive rate. But the amount must be high enough to make the investment in clean hydrogen cost-competitive with dirtier forms of hydrogen production or alternative energy solutions. This requires knowledge not only about technology and other project costs today, but also robust projections on how these costs are likely to change in the future. Governments are often advised to avoid policies that require a great deal of knowledge about a particular industry or technology, or otherwise may need to lean heavily on specialized consultants. Even the most skilled experts will make estimates that are riddled with uncertainty, as future circumstances, such as the price of other energy options, are bound to change.

- Subsidy thresholds may result in perverse incentives.

The U.S. tax credits are the most generous to hydrogen production that emits 4 kg of CO2e/kg or less, but this cap could stifle innovation to produce even cleaner hydrogen, since there is no incentive to go beyond that threshold. The more prescriptive the requirements for tax credit eligibility, the greater the opportunities for unintended consequences, with economic theory finding non-specific subsidies to be less distortionary. It should also be noted that costs of producing hydrogen will vary significantly depending on the jurisdiction across Canada, making regional winners likely to emerge under a blanket incentive scheme.

Lessons for Canada

The hydrogen sector is ripe for a global demand boom, with several regions jockeying for a greater share of global production. By 2050, hydrogen could represent as much as 10 per cent of global total final energy consumption, according to International Energy Agency estimates.

Canada is naturally positioned to compete in the international market for clean hydrogen, with a comparative advantage in abundant hydro resources, making clean power for electrolysis easy to come by, and providing a greater potential for green hydrogen to be produced at scale. Canada also has well-established expertise in linked areas, such as fuel cell production and carbon capture and storage. Any application of lessons from U.S. tax credit policy must therefore consider these Canadian-specific circumstances.

- Build Canada’s carbon price into policy design when examining relative costs of production domestically.

In order for clean hydrogen to compete domestically, it must become cost competitive with dirtier forms of production. The largest component of the costs associated with green hydrogen is the cost of renewable electricity, whereas the largest component of the costs associated with grey hydrogen is the cost of natural gas. In the U.S. the policy landscape only addresses the costs of green hydrogen, with tax credits bringing down project costs or offering a greater return on production. But in Canada, there is also a carbon price applied to fossil gas that is pushing in the opposite direction, pulling up the costs associated with grey hydrogen and changing the relative attractiveness of that option. In contrast to the U.S., where there is no price on pollution at the federal level, tax credit design in Canada will need to consider relative cost differentials with this carbon price included.

Effectively, Canada’s carbon price reduces the size of the tax credit required to effectively incentivize the desired action, pointing to a key difference between the U.S. and Canadian context that must inform domestic policy.

- Consider international competitiveness when determining the level of support for the tax credit.

There is no assurance that green hydrogen will be favoured over dirtier forms of the fuel internationally, and much of Canada’s green hydrogen export success will hinge on the climate ambitions of export markets. A tax credit designed to make green hydrogen more attractive than alternatives domestically, may be insufficient to see Canadian green hydrogen compete with alternatives internationally. Increasing the level of the green hydrogen tax credit to try to compete with dirtier forms of the fuel produced in international markets may not be efficient or practical. In addition, transport costs of the fuel to foreign markets become increasingly important. As a result, Canada will need to carefully consider its foreign market opportunities, targeting those regions likely to implement policies that favour the cleaner form of the fuel, such as the European Union, where it may better leverage its comparative advantage in clean electricity.

- Build performance metrics into subsidy payments.

Production tax credits have been viewed by economists as more efficient than investment tax credits, particularly when it comes to clean technology and energy, because production tax credits are more closely aligned to the final policy objectives—in this case, the production of clean hydrogen. Investment tax credits that are levelled purely against project costs risk spending public dollars inefficiently, as not all projects are successful, and costs can vary widely for the same outcome. While a generous 40 per cent investment tax credit looks set to move forward in Canada, it will be important to tie this incentive to final performance: the amount of clean hydrogen produced, and potentially other metrics related to nurturing the clean hydrogen ecosystem, such as regional training and development.

- Support and prioritize the full hydrogen ecosystem.

The U.S. looks set to target all three barriers to clean hydrogen growth: high-risk investments, high production costs, and a lack of infrastructure to support demand (for example, storage and transportation). In addition to the clean hydrogen investment tax credit and production tax credit, the U.S. Bipartisan Infrastructure Act, passed in November 2021, included US$1 billion for electrolysis research, US$0.5 billion for research and development of clean hydrogen manufacturing and recycling, and US$8 billion for regional clean hydrogen hubs. In Canada, continued support for research, development, and demonstration is likely needed, given that clean hydrogen has not yet achieved full technology maturity. And additional policies can help drive domestic demand for clean hydrogen, such as programs supporting clean hydrogen for heavy-duty vehicles and related infrastructure.

Conclusion

Tax credits have the potential to spur private-sector investment, including foreign direct investment, supporting Canada’s economic growth. Applying these credits to clean hydrogen can help build and strengthen the sector, supporting efficiencies through economies of scale, and helping provide a fuel that is expected to be required to meet Canada’s climate targets. Tax credits can also bolster the export potential of a clean fuel that may be increasingly in demand in a decarbonizing world. However, the cost of the policy to the public purse must be carefully considered, and technical expertise may be needed to ensure that the incentive is set at the right level to avoid free-riding behaviour. Canada may need to depend on the climate ambitions of its partners to see the clean hydrogen export market bloom. At the same time, Canada will need to build out its domestic market by supporting clean hydrogen end-use applications and transport infrastructure, and creating other conditions for a successful industry, including a rising price on carbon.

Longship carbon capture and storage in Norway’s North Sea

Introduction

Longship is envisioned to be a network of carbon capture and storage projects that could serve as one of Europe’s first large-scale initiatives to tackle industrial decarbonization, facilitating emissions reductions from heavy industries that are not able to fuel-switch or electrify. The megaproject has received considerable technical, operational, and financial support from Norway’s public sector, with the government expected to cover some two-thirds of total phase-one project costs, valued at over C$3.5 billion.

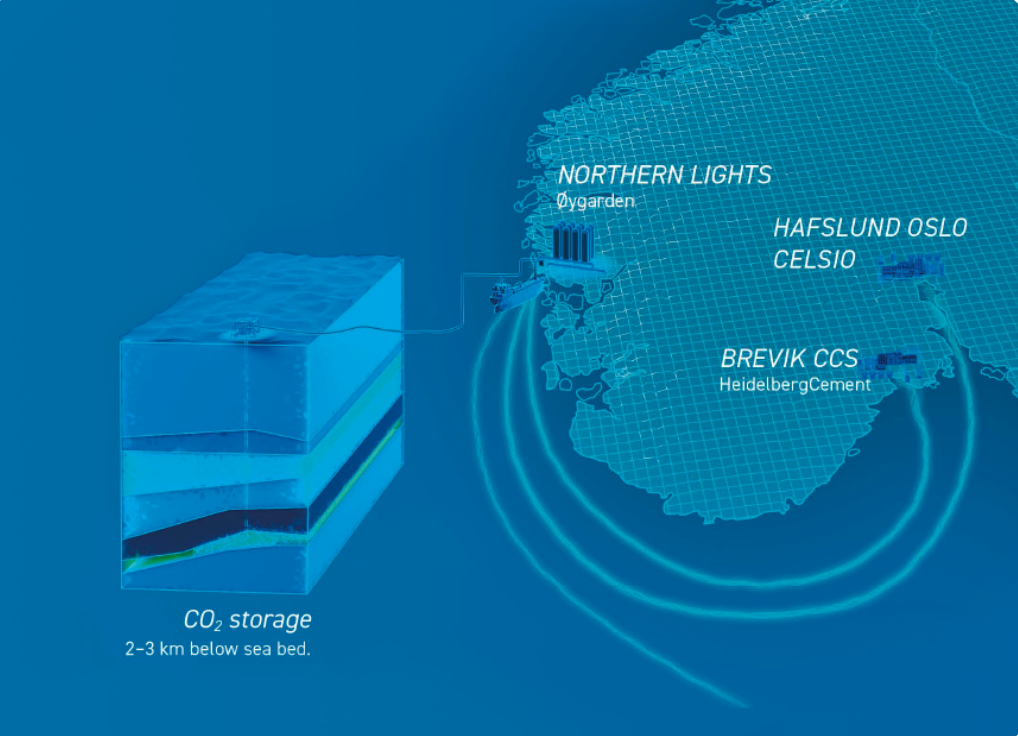

The Longship network will initially link two sub-projects that capture carbon dioxide from cement and waste-to-energy plants, with a storage plant in the North Sea. Norway’s state-led oil and gas company Equinor, along with oil majors Shell and Total, are partners to the Northern Lights portion of the project, the transport and storage facility, bringing significant experience in carbon dioxide storage in depleted offshore gas reservoirs. Construction of the Northern Lights terminal began in 2021, with the first phase expected to be complete by mid-2024, offering an initial storage capacity of 1.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide per year over 25 years. The aim of phase two is to increase storage capacity to 5-7 megatonnes per year by 2026.

Longship’s first sub-project is a carbon capture plant at a cement factory located in Brevik, owned by Norcem-Heldelberg, a subsidiary of Germany’s HeidelbergCement. The project aims to use surplus heat to capture 400,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, a third of the emissions caused from producing 1.2 megatonnes of cement per year. The second sub-project is a waste-to-energy plant located in the capital Oslo, the Hafslund Oslo Celsio (formerly named the Fortum Oslo Varme). The sub-project aims to match its sister’s capture rate at 400,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, with emissions captured from the waste combustion process. This sub-project tried but failed to obtain additional financial support from the European Union’s Innovation Fund, meaning that the Norwegian government had to commit additional financing to cover the investment gap.

Captured carbon dioxide from the two plants will be transported by ship to the Northern Lights reception terminal in Øygarden municipality, and then by pipeline to the injection well where storage will take place beneath the seabed. This portion of the project—the transport and storage infrastructure—aims to eventually become commercially profitable based on a tariff paid by emitting firms to transport and store their captured carbon dioxide.

Figure 1: Longship includes the full carbon capture chain through sub-projects linking captured carbon dioxide with storage

Longship provides an example of hands-on, targeted support for a large-scale emissions-abatement initiative, where the government works directly with its private-sector partners on project design, construction, implementation, and marketing. While subsidizing the lion’s share of phase one of the project, the government has said that phase two of the project, or any additional expansions, will need to be privately funded. The consortium of partners has already promoted the Northern Lights sub-project as commercially viable, aiming to become a storage provider for carbon captured from industrial sites across Europe.

Description of the policy

Norway has a long history of state ownership and other stakes in strategic industries, and this economic model has propelled the nation to one of the top-10 richest countries in the world. At the same time, Norway is known for its successful wealth distribution policies—including intergenerationally—made possible through its sovereign oil fund that manages revenue contributions from its petroleum sector. This reliance on its fossil fuel resource abundance, coupled with strong climate commitments (currently to cut emissions by at least half by 2030 compared to 1990 levels), has driven considerable interest in carbon capture and storage technology over the last two decades. Norway is now mobilizing its existing expertise, its ready access to North Sea storage, and a belief that a carbon capture and storage market will emerge as regional carbon pricing and other climate policies accelerate.

The Norwegian government launched the project through a white paper in September 2020, committing NOK 16.8 billion (C$2.32 billion) out of the total planned investment of NOK 25.1 billion (C$3.47 billion). Parliament approved the proposal at the end of that year, with the funding to roll out between 2021 and 2034, covering both capital and operational costs. This represents the Norwegian government’s largest ever investment in a single climate project. But the government’s support stretches beyond a financing role, to addressing other potential barriers to development, such as regulatory challenges.

State enterprise Gassnova was specifically established in 2005 to advance research and development into carbon capture and storage, and is now acting as the technical advisor to the government for Longship. This includes conducting the pre-feasibility study, leading in overall planning activities, and managing contracts with industry partners. Gassnova is also responsible for communicating results, and has committed to providing lessons learned from the regulatory and development processes to facilitate demonstration. Several other Norwegian public sector bodies are also heavily involved in the development of Longship, with several state agencies and directorates handling regulatory roles in addition to municipalities and county governors. The government is also involved as a project integrator, coordinating various public and private partners.

While phase one of Longship will connect only two plants capturing carbon dioxide in Norway with the Northern Lights facility, the network is envisioned to expand in later years. For the second phase, Northern Lights is offering commercial carbon storage services to companies across Europe, where emitting firms would pay a service charge for carbon dioxide handling and storage. European industrial sites that choose to capture carbon dioxide will be able to pipe or haul its liquified form onto ships that transport it to a facility on the Norwegian continental shelf before it is injected into permanent storage sites 2,600 metres below the seabed. Northern Lights has identified over 90 suitable capture sites, and there is already interest from industrial plants in eight countries, spanning sectors such as steel, biomass, and hydrogen.

Norway is promoting the project as a way to jumpstart a European carbon capture and storage market. While withdrawing its financial support in this commercial phase of the project, the government remains involved in bilateral relations, making agreements between participating governments a prerequisite for Northern Lights’ carbon dioxide storage agreements. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy is already in consultations with several governments, and has signed memorandums of understanding with Belgium and the Netherlands. This has paved the way for the first cross-border commercial agreement, signed in September 2022, that by 2025 will see up to 800,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year transported from Yara Sluiskil, an ammonia and fertilizer plant in the Netherlands, and stored.

While the Norwegian government is essentially designing and subsidizing a significant share of the project, it is simultaneously working to drive long-term demand for carbon capture. This includes a rising carbon price applied to fossil energy products such as petrol, diesel, and natural gas, currently slated to reach NOK 2000 (C$275) per tonne in 2030, up from NOK 590 (C$81) in 2021. The carbon price applies to sectors that are covered, as well as those that are not covered, by the European Emissions Trading System, with a pricing top-up currently applied to the former to reach the national benchmark.

While this strong carbon pricing trajectory will incentivize domestic industry to consider capturing their emissions, the carbon price applied within the European Union remains insufficient to do so. The targeted capacity at Northern Lights of 5-7 megatonnes per year by 2026 is a fraction of what is needed to help Europe decarbonize: a study by the University College London Energy Institute estimated it would require 230-430 megatonnes of carbon dioxide storage per year by 2030, increasing to 930-1,200 megatonnes of carbon dioxide storage per year by 2050 under a 1.5C-compatible scenario. For this reason, support-based policies are building in popularity under the European Commission, which has approved more state aid for carbon capture activities and also funds its own carbon capture and storage projects through its Innovation Fund.

Policy strengths and limitations

As the first large-scale carbon capture and storage project in the region, the Longship project has been called a “demonstration project,” helping to legitimize government support to test the technology as a climate change solution, including functionality, efficiency, and potential to scale. These types of public expenditures into clean technologies may help realize public benefits from innovation, including by building knowledge and related skills (the so-called “knowledge spillover” effect). The first-mover advantage—from being the first in Europe to enable cross-border carbon trade for storage—has also enabled the company to establish early partnerships and build a strong reputation in the market. Lessons learned may also bring down costs or remove other barriers that benefit future project proponents.

Many of the celebrated achievements of Longship thus far surround its success in overcoming financial and non-financial barriers to project implementation. While the large upfront capital costs of the project were identified as a significant barrier to development, the government has also helped to overcome other barriers to private-sector carbon capture development, such as regional red tape. This has meant trailblazing new public-private partnership models, and navigating a path to a more efficient regulatory process.

Strengths

- The project represents a strategic and specific investment with measurable results.

Unlike government policies that provide blanket support to industry, such as tax breaks or energy rebates, Longship is an example of a government targeting a specific project with measurable results and a potential revenue stream. These results include carbon capture as a key component of regional decarbonization, as well as tapping into the commercial opportunities of carbon dioxide storage across the region. As a public project, Longship defies market failures that prevented it from being realized by private actors, including high upfront capital costs, insufficient carbon price levels, and risks associated with the technology. In so doing, it targets a specific type, and volume, of climate change mitigation (i.e., 1.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide captured per year), and supports clean technology innovation. It also relies on a science-based approach to target which technology type to support, with carbon capture present in all globally recognized scenarios consistent with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C-2C.

- The government’s participation includes funding, designing, and managing the project through the full carbon capture and storage chain.

Recognizing that the concept of carbon capture does not work without a reliable storage option, the project has been designed to grow the entire carbon capture and storage chain in unison. Each component of the initiative is being considered as a separate sub-project, with the government establishing separate agreements with each industry player, thus helping to avoid cross-chain risk for private partners. While the model means that the government bears additional cross-chain risks related to the interface between the sub-projects, it protects private partners from weaknesses in other links of the chain. For example, if one of the capture projects were to fail, Northern Lights could find other carbon dioxide suppliers, or if Northern Lights were to fail, the capture projects could likely find a different storage provider without facing catastrophic loss.

- The project addresses a specific barrier to scale carbon capture and storage as a climate change solution: the availability of supporting infrastructure.

One of the identified barriers to carbon capture project development in Europe is uncertainty around transport costs and long-term storage options. Longship aims to address this well-known chicken-and-egg problem, where no industry emitter will invest in a capture project without the existence of a storage solution, and no company will develop a storage site without knowing that there is carbon dioxide to be stored. Longship will allow emitting firms to develop carbon-capture projects with the security of knowing there will be a reliable transport-and-storage option. The project has already mustered considerable interest from industrial emitters across Northern Europe.

- The project recognizes climate change as a global challenge, offering neighbouring countries a climate solution while also tapping into a emerging market.

As of 2021, there are over 50 carbon capture projects announced across Europe, offering an abatement potential of over 80 megatonnes of carbon dioxide per year. Many of these projects are considering Northern Lights for their storage requirements, particularly as the endeavour is several years ahead of other storage projects under development in Europe, such as the Port of Rotterdam Porthos Project. As a result, the project’s initial storage capacity is already oversubscribed if all agreements come to fruition. Longship also paves the way for blue hydrogen, where carbon is captured from the burning of natural gas in the production process. Equinor, for example, is already producing blue hydrogen in Hull, England as part of the Zero Carbon Humber carbon capture and storage project, and Northern Lights will provide a viable storage option for these types of endeavours. It should be noted that competition in the region is ramping up, with the U.K. investing £1 billion (C$1.66 billion) through a carbon capture infrastructure fund that is looking to develop two “hub and cluster” projects as early as 2025.

- The project helps address regulatory barriers.

Immature regulatory frameworks have been highlighted as a barrier to carbon capture project development worldwide. Working in lockstep with the federal government has allowed the project priority access through the regulatory process, and the government has demonstrated agility in shaping the system to facilitate project success—something that will help the next wave of carbon capture projects. Gassnova’s role in sharing lessons learned from the regulatory process has helped demystify the steps and shed light on potential hurdles in the Norwegian context. The importance of involving local authorities early in the process, for example, was highlighted as a key lesson learned due to the complexity and the sheer size of the carbon capture and storage projects. The Longship process has also helped shed light, and address hurdles such as zoning-plan permitting, consent for pipelines, and quay-to-offshore licensing. As a learning-by-doing model, the Longship project has already led to the development of a new licensing system for carbon dioxide storage. In addition, the government has now clarified reporting obligations for carbon capture to facilitate its international climate change reporting obligations.

Limitations

- The subsidy-based project relies on finite public capital to fund a technology with a mixed level of public support.

Longship has drawn criticism from some stakeholders who see public funding for the project as a form of fossil-fuel subsidy because it is an oil and gas consortium that hopes to benefit commercially from the storage and transport terminal. They note that the oil and gas sector has seen recent record profits and should not be given a share of finite resources from the public purse. Those critics also say that emissions-intensive companies should face regulations or carbon prices that incentivize carbon capture adoption—rather than relying on public funds. Some stakeholders also slam carbon capture as an inefficient or ineffective way of reaching net zero, believing that emissions should instead be reduced at source. While the government has doubled-down on carbon capture as “absolutely necessary” to reaching climate goals, they have also admitted that there is “no guarantee” that Longship will be a success from a climate change perspective.

- The ultimate success of the project hinges on the shape that domestic and international climate policy take.

Because the carbon price signal is currently insufficient to incentivize carbon capture development in Europe, additional government support is currently needed. The ultimate commercial success of the Longship project will hinge on the regulatory stringency and/or subsidy envelopes from other governments. This means that both ongoing and accelerating carbon price levels and government support are needed to see the carbon capture market take off. There are promising trends here, with four of the seven large-scale projects that were awarded funding in 2021 under the EU-level Innovation Fund considering carbon dioxide storage through Northern Lights, and seven out of seventeen winners from the 2022 Innovation Fund round including a carbon capture component. The upcoming third call will see a significant increase in funding, with the European Commission aiming to invest €3 billion (C$4.3 billion) towards clean tech projects.

Lessons for Canada

Canada’s oil and gas sector has been an early mover in carbon capture, and over three megatonnes of carbon dioxide are already being captured each year from Shell’s Quest Project, Alberta Carbon Trunk Line, and the SaskPower Boundary Dam Project. The Canadian federal government’s Emissions Reduction Plan set a target of capturing at least 15 additional megatonnes of carbon dioxide annually by 2030, including through a generous investment tax credit slated to be applied from the 2022 tax year onward.