SUMMARY

As climate change increases the risk of wildfires, individuals, communities, and governments will need to put more effort into protecting homes at the wildland-urban interface, where communities border on wilderness areas. Canada’s FireSmart program is a well-recognized and effective tool to support informed local action and help build capacity and knowledge. Additional regulatory and financial tools are, however, also needed to reduce costs from property damage.

CLIMATE CHANGE INCREASES THE RISK OF WILDFIRE FOR COMMUNITIES

As climate change leads to increased temperatures and drier conditions, wildfires are likely to become more frequent, grow more intense, and last longer across many regions in Canada. Studies show that the number of dry, windy days that let fires start and spread could increase by as much as 50% in western Canada and 200% in eastern Canada (Climate Atlas, 2020). In fact, wildfire activity has already increased, with the average area burned in recent years double the size of what it was in the early 1970s (NRCan, 2016).

Wildfires can be devastating and costly for communities and individuals. Researchers estimate the 2016 Fort McMurray fire cost almost $9 billion through physical, financial, health, mental, and environmental impacts (Snowdon, 2017). The fire destroyed more than 2,400 structures and displaced 85,000 people in the largest evacuation in Canadian history (Westhaver, 2017). One of the most compelling examples of the profound societal impact of the Fort McMurray fire was the staggering rise in mental health concerns such as depression and suicidal thoughts among grade 7-12 students eighteen months afterward (Brown et al. 2019).

Wildfire smoke can also affect the health of people far from the fire through reduced lung function, bronchitis, exacerbation of asthma, and increased risk of death. Air pollution from fires is a particular risk to pregnant women, children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing cardiovascular or respiratory conditions (BCCDC, 2020). Prolonged exposure to smoke from wildfires, as people in British Columbia and California experienced in 2018, increases the risk of immediate and future health problems. In addition, people living in wildfire-prone areas may experience exposure to smoke year after year.

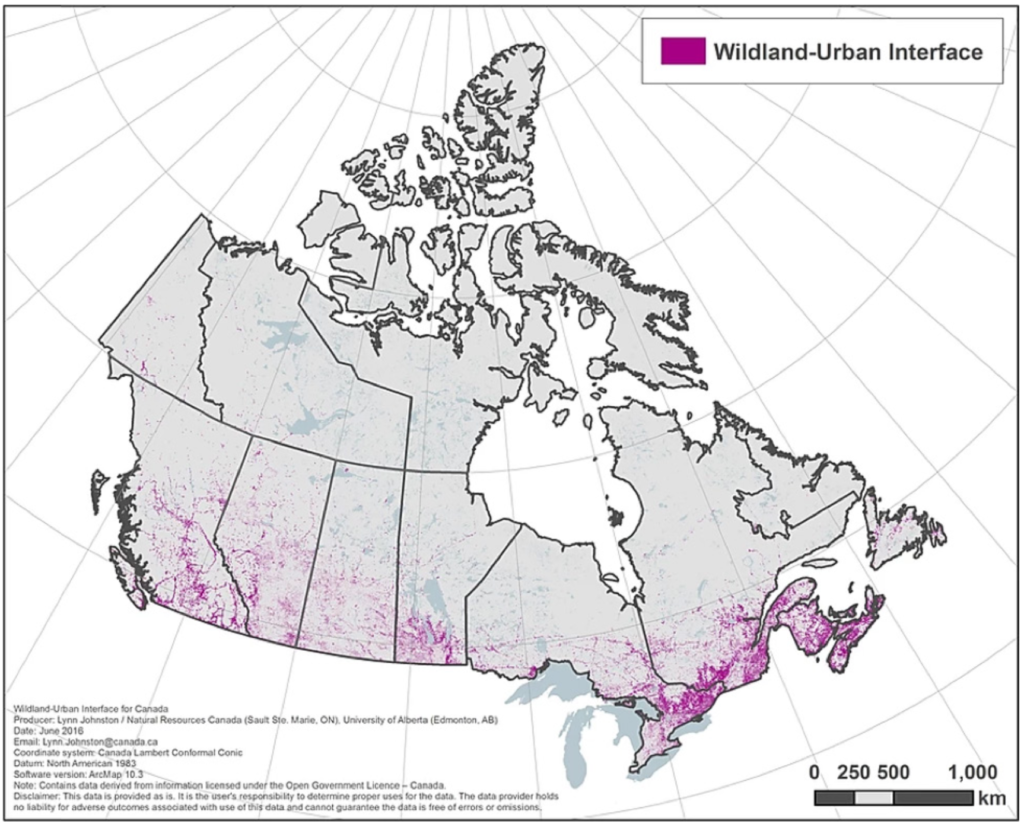

An increase in the frequency and intensity of fires will mean that we see more of these large-scale traumatic events. As Figure 1 illustrates, Canada has an estimated 32.3 million hectares of wildland-urban interface, with 60% of all cities, towns, settlements, and remote communities facing interface fire risk (Canada Wildfire, 2018).

Source: Canada Wildfire, 2018

HOW CAN COMMUNITIES REDUCE THEIR RISK?

After the Fort McMurray fire, people wondered why some homes survived and others did not. There were cases where the fire destroyed all homes in a neighbourhood except one. According to detailed assessments, most home ignitions were caused by embers from the forest fire, rather than direct contact with flames of the burning forest (Westhaver, 2017). So, the homes that survived must have either had features that protected them from embers, or the absence of common ignition hazards like leaves in gutters or a wooden deck.

Comparing the characteristics of homes after the fire, experts found that surviving homes had low to moderate hazard level across 20 factors for ignition potential. Destroyed homes predominantly had high to extreme hazard level ratings. The review did not find any one critical hazard factor. Rather, a single weakness could result in a home’s destruction (Westhaver, 2017). For instance, the ignition hazard could be a woodpile or shrubs next to the house, gutters with dried leaves, long grass, wood chips in the garden, wood siding, wood decks, or a roof with low fire resistance.

ALBERTA’S FIRESMART PROGRAM

One of the recommendations of the review of the Fort McMurray fire was to increase emphasis on reducing home vulnerability, through programs such as FireSmart. FireSmart, created by the Alberta-based multidisciplinary non-profit association Partners in Protection (PiP), helps communities and individuals take initiative to reduce their wildfire risk. It aims to build capacity and knowledge for people living in areas at risk of wildfire. Expanding from its roots in Alberta, FireSmart is now adopted in other provinces and at the national level (FireSmart Canada, 2018a). It receives funding from federal, provincial, and territorial governments, as well as insurance companies (ICLR, 2019).

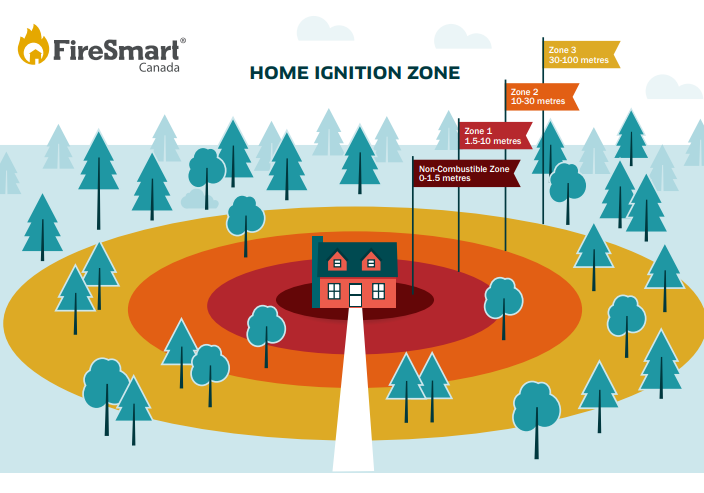

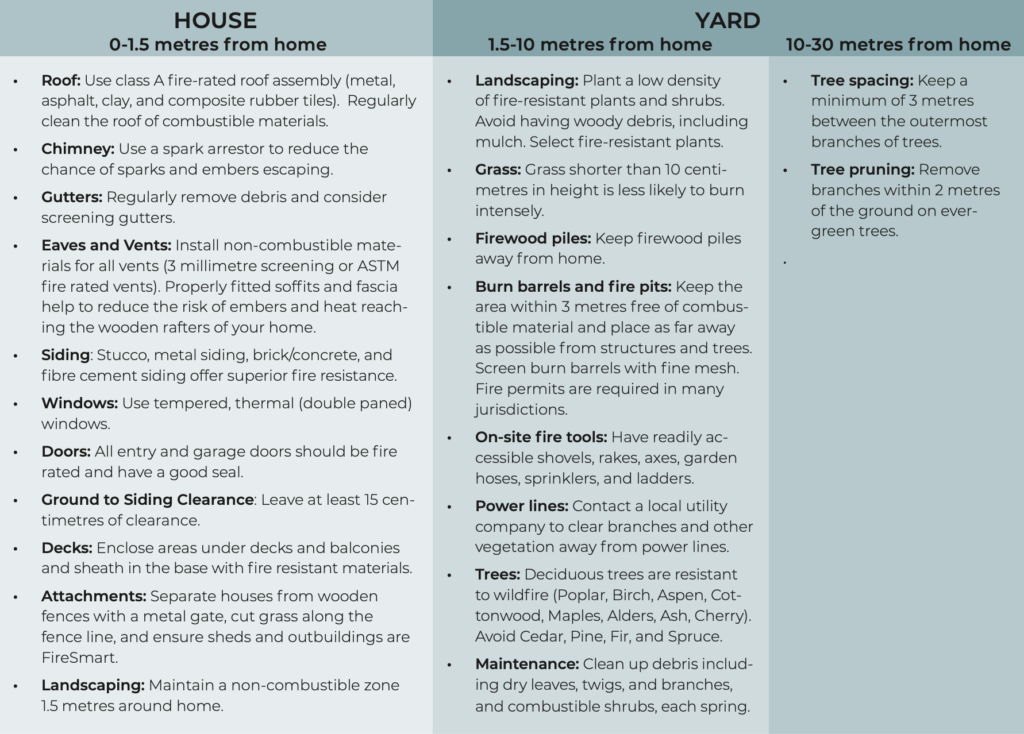

FireSmart recommends removing ignition hazards, including wooden decks and siding, within 10 metres of the home (Figure 2). Over the longer term, homeowners that have enough financial resources can invest in more costly solutions such as more protective roofing materials (FireSmart Canada, 2019a; 2018a; 2018b). For more detail, see table in this case study.

Source: FireSmart (2019b)

To help homeowners make decisions to reduce fire risk, FireSmart uses trained firefighters to assess homes directly, pointing out simple preventative measures as well as longer-term investment options. They then return after a couple of years to assess progress. FireSmart Alberta has also developed a mobile app that allows homeowners to conduct self-assessment and identify key vulnerabilities on their own, with access to information resources and expert networks.

For example, some types of roofs are more fire resistant than others. Class A materials, such as asphalt shingles, fibreglass, clay or concrete tiles, and metal roofing (with the old roof removed) are the most fire resistant. Class C materials, such as cedar shakes, have a low fire resistance (FireSmart Lesser Slave Region, 2020). Clear information can make it easier for homeowners to demand fire resistant roofing materials and techniques.

The FireSmart program also encourages entire communities to adopt a plan, track progress, and make investments in risk reduction. As more properties within a community adopt FireSmart practices, the heat and speed of fire can be reduced for everyone (FireSmart, 2019b). The town of Canmore, Alberta, won FireSmart’s Community Protection Achievement award in 2019. Its Wildfire Mitigation Strategy outlines FireSmart activities for the town and includes an updated hazard assessment, wildland fuel type and wildfire behaviour potential maps, and vegetation management options. It also makes recommendations for each of the seven FireSmart disciplines: vegetation management; development; public education; legislation; inter-agency cooperation; cross-training; and emergency planning (Canmore, 2020).

WHAT ELSE CAN BE DONE?

While FireSmart programs are a useful resource for homeowners, they place the burden of protection on individuals and communities—and not everyone is in a position to act. Homeowners may not be able to afford a new roof or siding. Lower-income, remote, and Indigenous communities may also have limited resources and competing priorities.

Strengthen Building Codes and Regulations

In 2016, a federal-provincial review found that most communities are not actively participating in FireSmart (CCFM, 2016). Experts have questioned whether there should be a greater role for provincial and federal governments in promoting fire resilience, given the broader public benefit of individual risk reduction efforts (Westhaver, 2017; Tymstra et al. 2019). Quebec is the only province that has regulatory standards that guide local governments in reducing wildfire risk (Tymstra et al. 2019). In most provinces and municipalities, building codes do not require builders to use fire resistant materials, which leaves homeowners shouldering the cost of renovation when seeking to reduce their risk. While new national codes are being developed to reflect climate change risk, it could be years before they trickle down to provincial codes (CP, 2020; ICLR, 2019). The National Fire Protection Association had proposed stricter building codes for wildland interface communities in 2011, but the idea was rejected at the time due to concerns about the burden of enforcement (CP, 2012). In the absence of building codes, FireSmart Canada, the Canadian Homebuilders Association, and the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation are working to develop a FireSmart checklist for developers and homebuilders building in wildland-urban interface areas (Moudrak, 2020).

Undertake Meaningful Consultation

Research by Walker (2020) also highlights the importance of meaningful consultation when FireSmart programs are implemented, particularly when wildfire risk extends across multiple jurisdictions in a small geographical area. When the FireSmart program was implemented in the La Ronge region of Saskatchewan, for example, some Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members voiced concerns over how the local vegetation was being cut back in areas used for medicinal plant gathering and land-based education programs.

Limit Urban Sprawl

Many cities also continue to sprawl further into the wild, seeking inexpensive land for residential developments, increasing their risk and the overall cost of wildfires (McMahon, 2018). Few governments have been willing to limit development, and wildfire hazard maps that could help identify areas unsuitable for development are not yet commonly available (ICLR, 2019).

Invest in Risk Reduction

The response of governments to a changing fire regime in Canada has thus far been largely reactive, with financing focused on wildfire response and recovery. However, it is increasingly clear that investment in risk reduction is significantly more cost effective (IAWF, 2020). Further, the most effective wildfire risk management strategies involve a combination of home ignition reduction (through programs such as FireSmart) and forest management practices that reduce the likelihood and severity of wildfires (Calkin et al., 2014). In preparation for a fire-prone future, proactive, largescale investment in these types of integrated strategies by federal, provincial, and local governments could dramatically reduce the impacts of wildfire on Canadians.

FIRESMART ADVICE FOR HOMEOWNERS IN WILDFIRE-PRONE AREAS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This case study was prepared by Rachel Samson of the Canadian Climate Institute, with staff contributions from Jonathan Arnold, Ryan Ness and Dylan Clark.

The Institute wishes to acknowledge the contributions of:

Blair Feltmate

Chair, Expert Panel on Adaptation, Canadian Climate Institute and Head, Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo

Natalia Moudrak

Director of Climate Resilience Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo

Laura Stewart

FireSmart Specialist, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Maureen G. Reed, PhD

Distinguished Professor and Assistant Director, Academic UNESCO Co-Chair in Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability, Reconciliation and Renewal School of Environment and Sustainability

Heidi Walker

PhD Candidate, University of Saskatchewan School of Environment and Sustainability

REFERENCES

BCCDC. 2020. “Wildfire Smoke and Your Health.” British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. http://www.bccdc.ca/ resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Health-Environment/BCCDC_WildFire_FactSheet_HowToPrepare.pdf

Brown, M.R.G., Agyapong, V., Greenshaw, A.J. et al. 2019. “After the Fort McMurray wildfire there are significant increases in mental health symptoms in grade 7–12 students compared to controls.” BMC Psychiatry 19, 18. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12888-018-2007-1

Canmore. 2020. “FireSmart.” Town of Canmore. https://canmore.ca/municipal-services/emergency-services/emergency-management/firesmart

Calkin et al. 2014. “How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Jan 2014, 111 (2) 746-751; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1315088111

Canada Wildfire. 2018. “Mapping Canadian wildland fire interface areas.” https://www.canadawildfire.org/mapping-wui

CCFM. 2016. “Canadian Wildland Fire Strategy: A 10-year Review and Renewed Call to Action.” Canadian Council of Forest Ministers. https://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications/download-pdf/37108

Climate Atlas of Canada. 2020. “Forest Fires and Climate Change.” https://climateatlas.ca/forest-fires-and-climate-change

CP. 2020. ‘‘A new focus for us’: Canada’s building code being modernized to address climate change.” CBC News. 1 January 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/climate-change-canada-building-codes-1.5412390

CP. 2012. “Building-code changes rejected for wildfire-prone areas.” CBC News. 3 December 2012. https://www.cbc.ca/ news/canada/edmonton/building-code-changes-rejected-for-wildfire-prone-areas-1.1177036

FireSmart Canada. 2020. “FireSmart Begins at Home Manual.”https://firesmartcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/ FS_Generic-HomeOwnersManual_Booklet-November-2018-Web.pdf

FireSmart Canada. 2019a. “FireSmart Community Recognition Program.” https://www.firesmartcanada.ca/ firesmart-communities/firesmart-canada-community-recognition-program/

FireSmart Canada. 2019b. “Ignition Zone.” https://www.firesmartcanada.ca/firesmart-communities/firesmart-canada-community-recognition-program/ignition-zone/

FireSmart Canada. 2018a. “About FireSmart.” https://www.firesmartcanada.ca/about-firesmart/

FireSmart Canada. 2018b. “FireSmart Home Assessment.” https://www.firesmartcanada.ca/mdocs-posts/ firesmart-home-assessment/

FireSmart Lesser Slave Region. 2020. “FireSmart for Homeowners.” https://livefiresmart.ca/homeowners/

IAWF. 2020. “Reduce Wildfire Risks or Pay More for Fire Disasters.” International Association for Wildland Fire. https:// www.iawfonline.org/article/reduce-wildfire-risks-or-pay-more-for-fire-disasters/

ICLR. 2019. “Fort McMurray Wildfire: Learning from Canada’s costliest disaster.” Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fort-McMurray-Wildfires_Canadian-Copright.FINAL-2_One-Page.pdf

McMahon, Tamsin. 2018. “In wildfire-prone B.C. and California, urban sprawl and bad planning are fuelling future infernos. What can we do?” The Globe and Mail. 24 February 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-in-wildfire-prone-bc-and-california-urban-sprawl-and-bad-planning/

Moudrak, Natalia. 2020. Personal Communication with Natalia Moudrak from the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation. https://www.intactcentreclimateadaptation.ca/

NRCan. 2016. “Peatland fires and carbon emissions.” Natural Resources Canada. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/climate-change/impacts-adaptations/climate-change-impacts-forests/forest-carbon/peatland-fires-carbon-emissions/13103

Reed, M.G. and Walker, H., with Fletcher, A. 2020. “Accounting for gender and diversity in adaptation planning and action: Speaking from Canadian experiences”. Presentation for Adaptation 2020, Feb 20, 2020. More information available from the authors.

Snowdon, Wallace. 2017. “Fort McMurray wildfire costs to reach almost $9B, new report says.” CBC News, 17 January 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/fort-mcmurray-wildfire-costs-to-reach-almost-9b-new-report-says-1.3939953

Stewart, Laura. 2019. Personal communication with Laura Stewart, FireSmart Provincial Representative for Alberta. June 2019.

Tymstra et al. 2019. “Wildfire Management in Canada: Review, challenges and opportunities.” Progress in Disaster Science. 5 (2020) 100045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100045

Walker, H. 2020 (forthcoming). “Building inclusive responses to climate hazards: Learning from experiences of wildfire in northern Saskatchewan.” (Doctoral dissertation in progress). University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada. More information available from author.

Westhaver, Alan. 2017. “Why Some Homes Survived: Learning from the Fort McMurray wildland/urban interface fire disaster.” https://www.iclr.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFS/why-some-homes-survived-learning-from-the-fort-mcmurray-wildland-urban-interface-fire-disaster.pdf