Introduction

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the United States is expected to channel at least US$370 billion in public funds to develop renewable energy, electric vehicles, clean fuels, advanced biofuels, and other clean technologies. It represents a generational investment in the clean energy transition—and one that is already paying dividends.

But despite its potential to transform the US economy on the path to net zero, the Inflation Reduction Act does not automatically translate to “shovels in the ground.”

Meeting the United States’ climate goal of net zero emissions by 2050 requires new clean electricity generation equivalent to constructing two 400-megawatt solar power stations every week for the next 30 years, according to one analysis. Yet it has historically taken four to five years to build this type of large-scale solar project in America.

The challenge is even greater for transmission infrastructure. Clean electricity will be the backbone of a net zero economy, but on average it takes over a decade to build new transmission lines. If the United States is unable to more than double the pace of transmission expansion, from 1 per cent a year to an average of 2.3 per cent a year from the present day until 2030, over 80 per cent of the potential emissions reductions created by the Inflation Reduction Act could go unrealized.

There are two main reasons why it takes so long to build clean energy projects in the United States. The first relates to the complex and time-intensive permitting processes that project proponents 1 must complete, often involving multiple levels of government. Second, local opposition to projects and the politicization of clean energy development can cause significant delays.

As this case study will explore, these two issues are related: permitting processes that lack sufficient community engagement can erode local support, trust, and buy-in for projects, adding delays to what are often already lengthy review processes. Consequently, lawmakers at the state and federal level have begun implementing reforms aimed at expediting permitting processes while strengthening community engagement to ensure that clean energy projects are built more quickly.

While the challenges with reforming federal permitting tend to get the most attention, this case study focuses specifically on state-level reforms. The majority of clean energy projects in the United States must acquire state level permits and undergo state assessments before proceeding with construction, whereas federal permitting processes often exempt projects that are expected to have insignificant impacts, including many clean energy projects. As a result, reforms at the state level can have a large impact on getting clean energy projects built expeditiously, and also have clear parallels with how provinces review and approve projects in Canada. State-level reforms can also provide rich examples of policy experimentation, where the most effective reforms can be adopted by other governments that are experiencing similar challenges.

Within this context, this case study examines permitting reforms implemented by New York and California, two of America’s most populous and economically powerful states, and also two climate policy leaders. Specifically, we look at whether these reforms are fully achieving the goal of getting projects built faster. It then concludes by exploring what lessons Canadian governments can glean from these experiences, particularly given the important jurisdictional and governance differences between the two countries.

How the permitting process for clean energy projects works in the United States

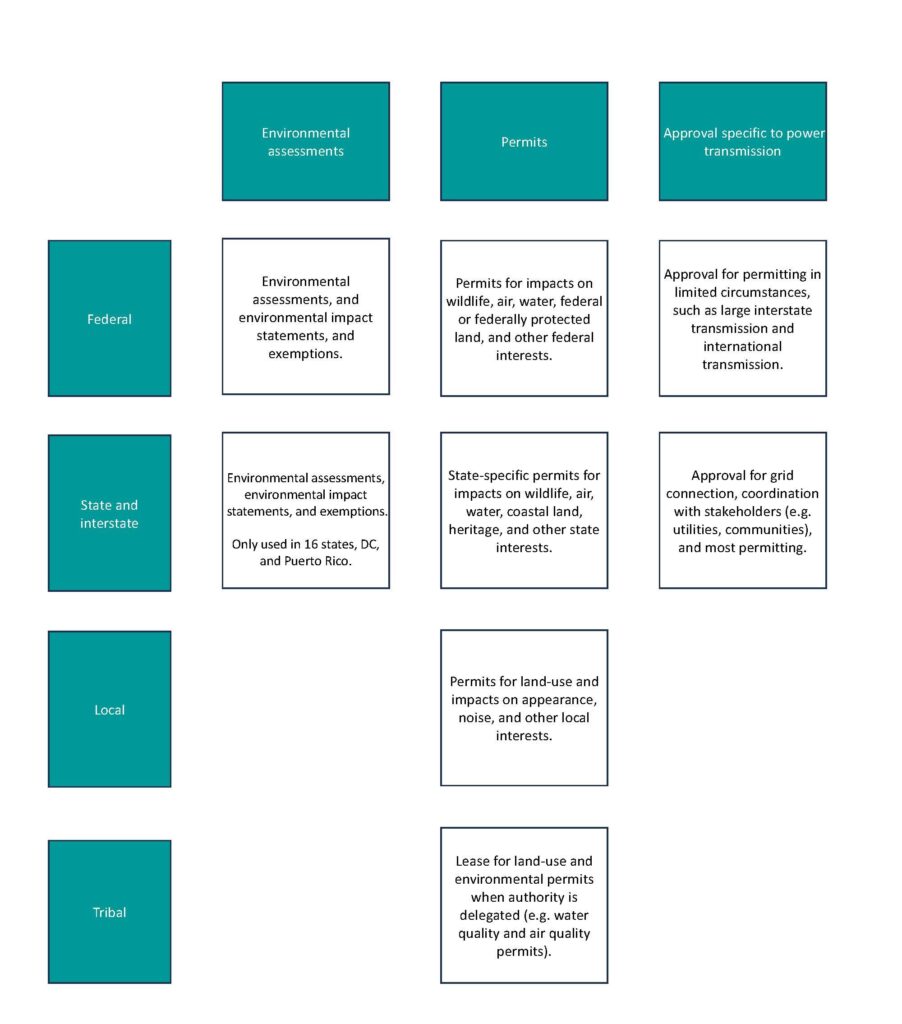

Figure 1 contextualizes state-level reforms within the bigger permitting process in the United States. While the process for any given project ultimately depends on the jurisdiction where it is located and the nature of the project itself, permits and environmental reviews can be triggered at local, state, regional or interstate, federal, and/or Indigenous (or tribal) levels of government. This complexity reflects the fact that the United States—like Canada—has a federal structure of government. As a result, there are multiple permitting processes from various orders of government that clean energy project proponents must comply with before they can proceed with construction.

Figure 1: Summary of project permitting processes in the United States

At the local level, every project—including projects in both New York and California—must acquire a land-use permit in compliance with local by-laws and zoning ordinances. At the state level, most governments (with few exceptions) require project proponents to apply for numerous permits, including both New York and California. For example, depending on the size of the project and the state in question, project proponents might have to apply for state-level permits and comply with state regulations and assessment frameworks, such as demonstrating compliance with endangered species or migratory bird protection laws. Additionally, a select number of states, including New York and California, have environmental review laws that require an assessment of a project’s environmental impacts before permits are granted.

The permitting process at other levels can overlap with the local and state-level processes. While outside of the scope of this case study, these warrant a few comments:

- Regional and interstate: Projects that cross state boundaries (e.g., renewable generation and transmission projects) are subject to additional approval from Independent System Operators which govern at either the state or interstate level. For example, renewable energy projects looking to connect to the electricity grid must apply for an interconnection request. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission also plays a role in permitting transmission projects in select cases.

- Federal: Larger projects have to apply for federal permits and undergo a federal environmental assessment (e.g., under the National Environmental Policy Act). Similar to the state level, there are various federal laws and regulations governed by a vast array of federal agencies that grant permits for various projects. In cases where multiple federal permits are required, a lead federal agency coordinates all permitting.

- Indigenous: Native American tribes were granted authority in 2012 to establish their own regulations, in accordance with Bureau of Indian Affairs guidelines2. However, granting long-term leases for clean energy projects on federally designated tribal lands still requires the approval of the Secretary of the Interior.

State-level regulatory reforms

New York and California have taken bold steps to expedite clean energy projects. This section provides an overview of the major changes underway.

New York

New York’s state legislature passed the Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act in 2020, the first comprehensive permitting reform at the state level.

The Act is multifaceted but centres around building out renewable energy generation capacity and significantly accelerating project approval timelines. It created the Office of Renewable Energy Siting to serve as a “one-stop shop” to address permitting challenges, conduct impact assessments, and to support project proponents to apply for state permits. It also established statutory time limits for issuing building permits, ranging from a maximum of six months for projects located on pre-approved brownfield sites to one year for all other projects. The Act also states that a permit will be automatically approved if the Office of Renewable Energy Siting does not make a determination within the required timeframe.

These reforms are primarily targeted at large-scale projects. Only projects with a capacity of 25 megawatts or greater will be administered through the Office of Renewable Energy Siting. However, projects with a capacity ranging from 20 to 25 megawatts are eligible to opt into the Office of Renewable Energy Siting process.

In aggregate, these regulatory changes could dramatically shorten permitting process timelines. Prior to the passage of the Act, it took approximately five to ten years to get renewable energy projects to the construction stage—a clear impediment to achieving New York state’s legally-binding target of 70 per cent renewable electricity generation by 2030. Under the new process, renewable energy projects could conceivably get approved in as few as two years.

The Act also creates a Build-Ready program that allows the private sector to proactively identify and nominate brownfield sites for renewable energy development—sites that have, at some point in the past, received project approvals for economic development (for example, a retired industrial plant). If deemed viable, the New York State Energy and Research and Development Authority works closely with municipalities to advance the permitting and interconnection process. Once the site is fully permitted and approved, it is auctioned off to private renewable energy developers.

New York’s Accelerated Renewable Energy Growth and Community Benefit Act also includes provisions for community benefits and employment. All new renewable energy projects administered through the Office of Renewable Energy Siting and the New York State Energy and Research and Development Authority are required to provide a benefit package for the host community of the project in the form of utility bill credits and other community benefits. These benefit packages are intended to help get community buy-in early in the process to reduce the likelihood of opposition and future delays. Additionally, the Act provides funding for communities to intervene in the approval process to ensure that they’re receiving tangible benefits from proposed projects.

Lastly, the Act authorizes an expedited permitting process for transmission projects in existing rights-of-way and creates a program to invest in distribution and local transmission capital plans to meet the state’s climate goals.

California

Clean energy project construction in the state of California is notoriously difficult. California Governor Gavin Newsom recently stated in an interview that “people are losing trust and confidence in our ability to build big things.” And the data backs that up. Among all the western states, approvals for new clean energy projects take the longest in California.

Climate change, and the need to dramatically cut state-wide emissions, have put these regulatory barriers in clearer focus. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events in the state, such as recent heat waves and wildfires, have repeatedly threatened the capacity, reliability, and financial viability of the electricity grid. Moreover, the state needs to dramatically increase its supply of clean energy to achieve its climate targets.

Consequently, in 2022 California started reforming its permitting process, starting with Assembly Bill 205.

In many respects, the bill mirrors the reforms implemented in New York. It provides the California Energy Commission with the sole authority over permitting for wind and solar projects over 50 megawatts and storage projects over 200 megawatt-hours. Assembly Bill 205 also establishes statutory limits of 270 days for Environmental Impact Reviews.

The California reforms also include requirements for community and employment benefits, similar to those in New York. Assembly Bill 205 mandates the inclusion of community benefit plans in project approval to address or mitigate local opposition, and establishes labour and prevailing wage standards as a prerequisite for projects to enter into this newly established process under the California Energy Commission. Project proponents are required to partner with one or more community-based organizations to provide job training, community assets like parks, and investments in public infrastructure. The California Energy Commission can also place various other conditions for project approval as a means to address local concerns.

Strengths of the regulatory reforms

Both the New York and California regulatory reforms have the potential to expedite clean energy projects and generate local economic benefits while upholding environmental protections. The reforms have several core strengths, including:

1) Providing more certain timelines for project proponents can make a greater number of vital clean energy projects financially viable.

Lengthy permitting processes for clean energy projects do not just slow projects down; they also adversely affect the bankability and economic viability of a project. Project proponents need to invest in engagement efforts with local communities and Indigenous Peoples and hire lawyers to navigate the complex administrative processes. At the same time, project proponents need to continue paying their employees during the regulatory process, which is especially challenging given that projects are not generating revenue at this stage. Ultimately, repeated delays might force project proponents to seek additional financing—which becomes increasingly challenging over time—or abandon the project altogether 3.

The reformed system in New York has already proven to be faster and more predictable than the previous process. Publicly available data indicates that of the eight renewable projects entirely handled through the new Office of Renewable Energy Siting process, it has taken less than eight months on average to receive a permit. Only one project took a full year to issue a permit, the maximum allowed by law.

Initial data indicates that these reforms in New York have also helped cut the entire timeline for getting projects built, from start to finish. Before the Act, the entire process could take five to ten years; after its passing, seven of eight projects were approved within two years, and the eighth took two years and one month.

The California reform, by contrast, is too new to determine its effects on permitting timelines. But given that it implemented similar changes to the New York reform, it is positioned to drive similar results.

2) Mandating community benefit agreements can help reduce local opposition and expedite the permitting process.

A recent U.S. study showed that concerns about decreasing land values were the most common concern expressed by locals opposed to clean energy projects. The analysis also indicated that project opponents believe that the site of a clean energy project could be put toward a more productive use for their local community. Lastly, the analysis found that feelings of not being heard or adequately integrated into the permitting process increased local opposition. Misinformation about the purported harms of renewables also poses challenges for renewable projects seeking local land-use permits.

The reforms in both New York and California require community benefit agreements between the project proponents and the local community. They are designed to generate tangible benefits for host communities to offset the types of concerns that have historically delayed or cancelled project development. Benefit agreements can help address concerns over property values and land use by encouraging investments in community centres, schools, and other valuable community resources. For example, EDF Renewables’ Tracy Solar Energy Center project, permitted under New York State’s Office of Renewable Energy Siting, plans to dedicate US$20,000 annually to local and community-driven initiatives in the project area over a period of ten years once the site becomes operational in 2025.

New York even goes a step further by requiring project proponents to provide utility bill credits to affected communities and funding to facilitate community involvement in clean energy projects. The proposed Mill Point Solar I project, for example, commits to providing US$1.25 million over the first ten years to be distributed evenly across utility customers within the Town of Glen. These types of agreements help community members to participate in the permitting process and the energy transition more broadly.

An additional strength of community benefit agreements is that they indirectly prioritize projects that are more financially stable. Developing such agreements takes a high degree of coordination, planning, and strong financials, all of which helps screen out weaker projects.

Overall, embedding community benefit agreements can help set and formalize expectations for both communities and proponents, speeding up the process and getting the buy-in of the local community. Both states’ reforms operate from the assumption that well-designed benefit agreements are a necessary investment in sustaining local support for the project, and the earlier these agreements are established the better.

3) Eliminating all of the permitting costs for clean energy projects on brownfield sites helps to ensure that more get built.

New York’s Build-Ready program flips the script on the permitting process for clean energy projects. By identifying, evaluating, and permitting brownfield sites for clean energy project development while simultaneously engaging with local communities to create a benefits package, the Program eliminates all of the costs and uncertainty for project proponents associated with the permitting process. Once the permits and interconnection requests have been approved and the site has been auctioned off to a project proponent, construction can begin right away without fear of the project being tied up in regulatory delays and with limited risk of litigation.

The California reforms, by contrast, do not include any provisions to accelerate projects on brownfield sites.

4) Setting time limits on litigation and judicial reviews should reduce costs for project proponents.

Lawsuits against development projects in the United States, often filed by local citizens concerned about the social or environmental impacts to the community, occur frequently. These disputes create a substantial obstacle to speeding up the construction of clean energy projects, both on a local and national scale, even when efforts are made to simplify the process of selecting project sites.

Legal actions are particularly pervasive in California, where, under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), “public projects” have been interpreted to include any private development. Court challenges stating that a CEQA review was incomplete or insufficient are cheap and simple to file, and can be done anonymously. Such filings can add significant delays to clean energy projects, or even scare away developers from making a proposal in the first place.

The reforms in California’s Assembly Bill 205 are attempting to address this issue by establishing a statutory limit on the timeline for judicial reviews. It aims to reduce litigation costs for project proponents and minimize the effectiveness of frivolous lawsuits.

It is still unclear, however, whether these reforms will have their intended effect. Statutory time limits could, for example, impede citizens from raising valid concerns with clean energy projects. Other tools, such as stronger anti-SLAPP legislation—which aims to reduce bad faith attempts to limit or compromise public processes—or ending the practice of anonymous filings could be considered to help address frivolous litigation. Moving forward, legal strategies to slow down or stop clean energy projects will likely remain a major source of resistance in the regulatory review process in both jurisdictions.

5) The ability to opt-in to accelerated permitting processes can give project developers added flexibility.

California’s reform creates an opt-in system, which allows project proponents to “forum shop.” For example, if the project site is in a jurisdiction that is heavily in favour of renewable development, they could choose not to opt-in to the California Energy Commission process. However, if proponents encounter local resistance, or if they are looking to build in a community that lacks experience with renewable projects, they can bypass the local level as the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction over all permitting if a project opts-in.

This added flexibility allows project developers to choose the smoothest path through the permitting process, reducing the time it takes to get projects built.

However, similar to the time constraints on legal action, this provision in the Californian reform could have unintended consequences by minimizing or skirting legitimate concerns at the local level. The extent to which this becomes a problem depends largely on implementation by the state. Provisions within the new California Energy Commission process require the state to ensure projects are in the public interest, which could help address these potential impacts.

6) Minimum thresholds for project size helps prioritize larger projects, which often face the biggest barriers.

The reforms in both states are designed to accelerate big projects. In New York, the new permitting and regulatory processes are only applicable for projects exceeding 20 megawatts. In California, renewable projects must produce over 50 megawatts in power and storage projects over 200 megawatt-hours to be eligible.

Prioritizing larger clean energy projects in the regulatory reforms makes sense for a few reasons. Larger projects typically face a higher degree of scrutiny in the permitting process due to their larger environmental impacts. As a result, the permitting process for bigger projects often involve more decision points and overlapping layers of government, and are therefore more likely to face unnecessary delay and friction. At the same time, the stakes are higher for getting big projects built: they have the potential to generate economies of scale that can both close the states’ clean energy gap while generating significant local benefits.

It is worth noting, however, that smaller-scale projects can also run into similar challenges as larger projects but would be ineligible to access expedited permitting processes to address those challenges. Small-scale projects are likely to have even greater financial difficulties arising from regulatory delays suggesting that additional reforms targeting small-scale project proponents could be beneficial. In these circumstances, a framework to fast-track small- and medium-sized projects that meet minimum standards, in terms of environmental and social impacts, could be helpful.

Limitations of the reforms

Even though the permitting reforms in New York and California are still new and have yet to be fully implemented, limitations are already starting to emerge. If left unaddressed, these limitations could undermine the efficacy of the reforms and, in some cases, lead to unintended consequences.

1) Vague language in the California reform risks jeopardizing its effectiveness.

Although the California reform sets ambitious statutory targets to expedite permitting processes, vague language throughout the law could impede those efforts. For instance, the 270-day time limit for Environmental Impact Reviews can be extended if there are “substantial changes . . . that may involve new significant impacts . . . ; new information of substantial importance . . . is submitted;” or if the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and/or the State Water Resources Control Board determine that they need more time to obtain information. In fact, the plain language of the law states that the California Energy Commission must certify an Impact Review and issue a decision on an application “no later than 270 days after the application is deemed complete, or as soon as practicable thereafter.” That qualifier, “or as soon as practicable thereafter” is particularly broad and could be abused.

2) Expediting the permitting process could compromise the rights of Indigenous Nations and people in both California and New York.

Under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which the United States has not endorsed but announced in 2010 it supports, ensuring the free, prior, and informed consent of affected Indigenous people is an essential component of project development. Fulfilling these obligations under UNDRIP requires relationship building with affected Indigenous nations and communities, which takes time and effort. As Trent Fequet, the CEO of the Steel River Group, an Indigenous business management firm, has stated, “when building relationships, it can only be done at the speed of trust,” and that means engagement early, often, and in community.

Yet the push to expedite permitting processes could compromise the objective of free, prior, and informed consent as outlined in UNDRIP.

California has made a stronger effort to integrate Indigenous rights and title within the permitting process. The state of California is required, for example, to provide the project application to California Native American tribes “that are culturally and traditionally associated with the geographic area of the site and initiate consultation with those tribes.” The state is also required to integrate traditional Indigenous knowledge within the permitting process, and project proponents must include affected tribes within community benefit agreements.

Even with these commitments, however, the prescribed time limits for the permitting process in California could lead to inclusion of Indigenous Nations that falls short of the UNDRIP principles. Unlike in Canada, the United States does not have an established legalconstitutional obligation to engage or even consult Indigenous governments before taking permitting actions that would significantly impact them. The vague language around the permitting process timelines (highlighted above) may provide some room for accommodation; however, it is still too early to determine how these extensions could be applied in practice.

It is noteworthy that the text of the New York reform bill, by comparison, includes no such commitments or language around Indigenous rights and title in the permitting process.

3) Both reforms increase administrative efficiency, but it is unclear whether staffing capacity will be sufficient to match the expected increase in clean energy projects over the coming years.

At the national and state level in the United States, limited agency capacity is one of the primary causes of permitting and other regulatory delays. Sustained, long-term funding and workforce planning to recruit experienced and knowledgeable staff are vital to ensuring that projects are reviewed in a timely manner. Scaling up administrative capacity to match the sharp increase in clean energy projects is critical for their timely completion.

The reforms in New York and California are designed to streamline the project permitting process and, as a result, help address these gaps in administrative capacity. The new permitting office in New York, for example, is specifically designed to put the previously disparate administrative resources under one roof.

It is unclear, however, whether the reforms in either state are sufficient to ensure the necessary administrative capacity to meet the significant increase in applications. California has proposed providing, but has not yet budgeted for, additional, long-term funding to the California Energy Commission.

4) Clean energy interconnections are not adequately addressed by either reform, which highlights the federal government’s important role.

The process for connecting clean energy projects to the grid is often lengthy in the United States. Interconnection requests are evaluated sequentially (in the order that they apply) by Independent System Operators or Regional System Operators, which has created a backlog that is, in many cases, years long. As of the end of 2021, 1.4 terawatts (1,400 gigawatts) of power generation and storage capacity was awaiting interconnection throughout the United States, triple the amount queued up in 2016. California’s Independent System Operators queue has more than quintupled since 2014; in New York, the queue has increased from approximately 10 gigawatts in 2014 to roughly 75 gigawatts in 2021.

That has led numerous clean energy project proponents to abandon their projects, with only 23 per cent of all proposed projects reaching completion across the United States, a rate that is declining. In fact, across the country, California and New York’s Independent System Operators have the lowest rates of projects that reach commercial operation, at 13 and 17 per cent respectively.

Unfortunately, California’s reform does not adequately address these interconnection challenges. Assembly Bill 205 does not make any changes to CAISO, its Independent System Operator. Efforts by New York to expedite its permitting processes and invest in distribution and local transmission capital plans hold promise, but ultimately, such efforts may not be sufficient. Transmission across state boundaries exceeds state authority, falling within federal jurisdiction.

Recent announcements suggest that the federal government is starting to fill this gap. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission recently had its backstop permitting authority expanded. If it were extended further, it could address even more of the interconnection challenges. Moreover, the Department of Energy released its proposed Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits Program in August 2023, which would set a two-year limit on permitting reviews and would streamline the application process.

Lessons for Canada

The permitting reforms in California and New York have great potential to speed up assessment and approval processes for clean energy projects. They are designed to not only shorten the timeframe for getting projects approved and built, but they include explicit provisions to share the benefits with local communities. This combination is designed to secure local buy-in earlier in the process and remove unnecessary friction, while still upholding the environmental and social standards that these processes were originally designed to protect. The strengths and limitations of these reforms are summarized in Table 1—the identified limitations serve to highlight areas for future improvement and additional research.

Table 1: Strengths and limitations of New York and California’s permitting reforms for clean energy projects

| Strengths | Limitations |

| 1. Clear project timelines boost clean energy project financial viability. | 1. Vague language in the California reform puts its effectiveness at risk. |

| 2. Mandatory community benefit agreements can reduce local opposition, increasing permitting speed. | 2. Expedited permitting may adversely impact Indigenous Nations and people’s rights. |

| 3. Removing permitting costs on brownfield sites accelerates clean energy project development. | 3. Both reforms aim for administrative efficiency, but the state of required staffing capacities remain unclear. |

| 4. Time limits on litigation can reduce project proponent costs. | 4. Neither reform addresses interstate electricity transmission, underlining the Federal government’s crucial role in this aspect. |

| 5. Opting into accelerated permitting offers developers more flexibility. | |

| 6. Minimum project size thresholds prioritize larger, barrier-prone projects. |

The reforms—both their strengths and limitations—offer some important insights for Canada, which faces similar challenges in rapidly scaling up clean energy projects to meet its climate commitments. And like the United States, frictions in regulatory review and permitting processes have been identified as a major barrier to getting these projects built quickly. The different structures of government between the United States and Canada—including the different division of powers between the federal government and states/provinces— mean that not all lessons are directly transferable. However, we identify a number of important insights that could help drive progress in Canada.

First, the experience in New York (and, to a lesser extent, California) shows the value in establishing a “one-stop shop” for streamlining permitting processes. Second, the introduction of statutory time limits could provide developers in Canada with greater regulatory certainty and reduce unnecessary costs and delays. Third, New York’s program to proactively nominate and approve development on brownfield sites is another idea that could open up new possibilities for development in Canada, where environmental reviews on such sites can likely be shortened (particularly in cases where the new activity clearly has smaller environmental impacts than the activity originally commissioned on the site). Finally, the mandatory inclusion of benefit packages for host communities could reap similar gains in Canada and help secure local buy-in earlier in the permitting process.

The shortfalls and limitations in each state also hold important lessons for Canadian governments. The California reforms highlight the dangers that accompany vague language when setting timelines for review processes, which may create loopholes that undermine the original intent of providing greater regulatory certainty for project developers. Secondly, the experience in both states emphasizes the importance of ensuring that any type of regulatory reform or shortening of timelines is consistent with the principles under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Here, the context is clearly different between countries. Canada has a constitutional responsibility to ensure meaningful consultation and engagement with Indigenous Nations and communities, whereas the United States has not formally endorsed UNDRIP. Canada’s federal government passed the UNDRIP Act in 2021; however, it is still unclear how this Act will be operationalized in project permitting processes. In fact, these commitments make any type of new time limits on the permitting process even more challenging within the Canadian context, suggesting that governments would need to proceed more carefully than in the United States.

Another insight for Canada comes from the inadequate administrative capacity in each state, highlighting the importance of ensuring that any procedural reforms in Canada are matched with sufficient staffing to process a higher number of applications and environmental reviews. Finally, the inadequate focus of the United States reforms on transmission projects and interconnectivity across state boundaries should motivate Canadian governments to give the key issue of interprovincial transmission lines special attention and careful consideration in regulatory reforms.

Canadian governments can and should learn from experiences in other jurisdictions as they attempt to address their own challenges with sluggish permitting processes. However, fully leveraging the lessons from other countries requires a more complete understanding of the sometimes unique barriers holding back project development in Canada. While it is clear that clean energy projects are not getting built at a pace consistent with the country’s climate objectives, it is not yet entirely clear where the biggest pinch points are within the Canadian system. Without an accurate and accepted diagnosis of current weaknesses, no amount of permitting reform can provide relief in the long term. Ongoing research at the Canadian Climate Institute is exploring these specific barriers in more detail, which can put governments in a better position to implement the lessons from other countries.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the substantive contributions made by Jared Forman to drafts of this case study when he was a member of staff at the Institute in 2023.

References

- The permitting processes described in this section are applicable to all projects, not only clean energy projects. However, for the purposes of this paper, we are only interested in how clean energy projects—including generation, transmission, distribution, and storage—can be expedited and therefore only refer to these project types.

- Note that we use American terminology in this case study when referring to Indigenous Nations and Peoples.

- It is important to note that project delays are not always caused by governments. Proponents often contribute to delays, for example by submitting incomplete or inadequate documentation, or by shifting resources to other corporate priorities during the process (Roosevelt Institute 2023).