Tansi, Sandra Lamouche nitsikason, niya nehiyaw iskwew. Bigstone Cree Nation ochi niya. Hello, my name is Sandra Lamouche. I am from the Bigstone Cree Nation.

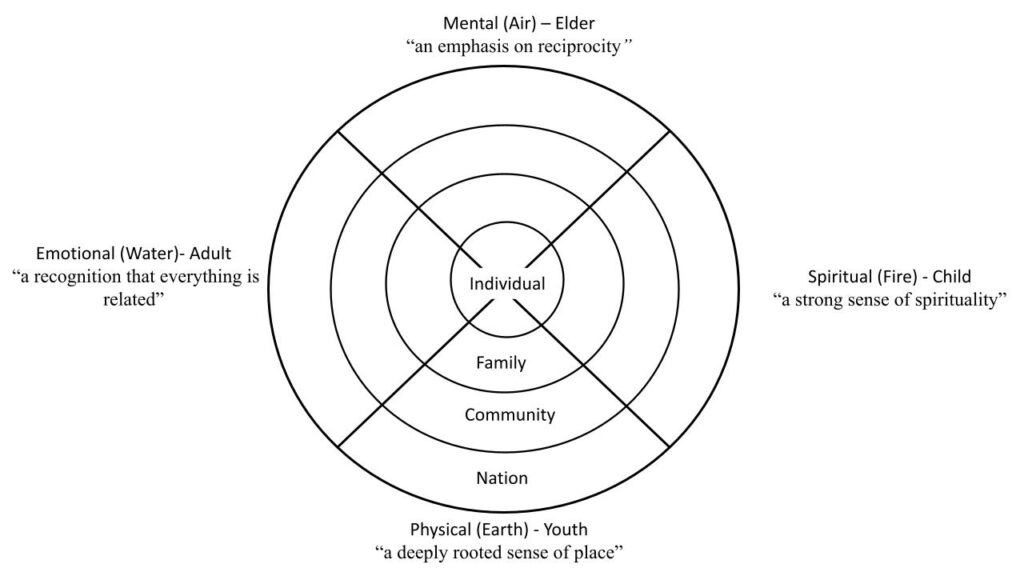

This case study was inspired by my thesis research “Ê-Nihtohnak Miyo-Pimatisiwin (Seeking the Good Life) Through Indigenous Dance” and how individuals relate to and are guided by each direction of the nehiyawak (Plains Cree) medicine wheel. The wheel includes the four cardinal directions, four elements, and the four aspects of human beings—spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental (See image 1)—and is holistic, helping us to live a healthy and balanced way of life. It contains concentric circles with the individual in the centre and moves outwards to family and friends, then community, with the nation on the outermost circle. This is symbolic of how our individual actions influence our world and others.

The spiritual aspect of culture and identity on the wheel, which is taught through story, is especially important as it teaches us about the possibility for change and transformation. It shows how we can change behaviour—both our own and collectively—to align with and embody the lessons and worldviews of traditional stories. I use a nehiyawak medicine wheel as a framework to understand a nehiyawak story to reveal the lessons it has for changing our behaviour in relation to climate action and the specific policy changes we push for from companies, governments, and our leaders.

Indigenous stories can help us make effective and impactful progress because they are specific to the land we live on and “in order to do what the climate crisis demands of us, we have to find stories of a livable future, stories of popular power, stories that motivate people to do what it takes to make the world we need” (Solnit 2023).

Racism as a barrier to Indigenous inclusion in climate change policy

Indigenous rights are being violated in Canadian climate change policy as the voices of Indigenous people are not yet fully included in climate change research. In some cases Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and approaches to climate change are ignored (Reed et al. 2021) and this has reinforced colonial relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. My own experience has taught me that there is a lack of knowledge and understanding about Indigenous cultures, which leads to them being devalued and dismissed.

One reason Indigenous Peoples continue to be excluded from spaces where climate policies are designed and implemented, is that ongoing racism dismisses Indigenous knowledge and worldview in favour of western and Eurocentric knowledge and thought. As Charlotte Reading describes, “science has emerged as one of the most dangerous tools of colonial domination, as disciplines of science have created and maintained racial distinctions used to segregate and oppress Indigenous peoples” (Reading 2020). This dismissal has deep roots in colonial oppression which was based on the western worldview that Indigenous cultures and knowledge were “uncivilized”, “primitive”, or “inferior”. This view was reflected in residential school policies as the system was based on an assumption that European civilization and Christian religions were superior to Indigenous cultures (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2017). Call to Action 57 from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s recommendations shows anti-racism work is critical to transformational change:

“We call upon federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to provide education to public servants on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal-Crown relations. This will require skills based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2017).

Systemic racism severs Indigenous stories from place by prioritizing western worldview over Indigenous ways of knowing and being. It is therefore important to fulfil the Call to Action 57 in order to have Indigenous knowledge recognized for its valuable expertise and the ways in which it can inform direction and solutions to many different challenges our society faces, and especially issues of climate change. The TRC Commissioners also note that they repeatedly heard the message that reconciliation in Canada requires reconciliation with the earth (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2017).

The power of Indigenous story to change our behaviour and inform climate action

Anti-Indigenous racism often leads to valuable knowledge and expertise from Indigenous people being left out of decisions and/or policies related to climate change that could make them stronger and more impactful (Reading 2020). Braiding Sweetgrass asks us to see Indigenous stories “not as an artifact of the past but as instructions for the future” (Kimmerer 2013). Jo-Ann Archibald talks about the importance of understanding Indigenous “storywork” (a term she coined) as it “signifies that our stories and storytelling should be taken seriously” (2008). For example, one of the problems with western approaches to climate change is that they focus on the symptoms rather than the root causes (Reed et al. 2021). Indigenous stories can help shift that approach as they are tied to Indigenous pedagogy and a more holistic worldview that recognizes the interconnectedness of the natural world.

Often in nehiyawak thought we use the past as a guide for our future—a common saying is that you need to know where you’ve been in order to know where you are going (Bell 2006). In contrast to the western worldview, Indigenous stories also include valuable knowledge that instructs us to live in a sustainable, balanced way with the earth.

To demonstrate and learn from the knowledge and expertise woven into Indigenous stories it is important to understand them through an Indigenous worldview, and the nehiyawak medicine wheel helps us do this. Nehiyawak stories speak to all aspects of the nehiyawak medicine wheel, as they carry wisdom (mental aspect in the northern direction of the wheel), explain the world (physical aspect in the southern direction), while also teach about relationships (emotional in the western direction), and our culture and identity (spiritual in the eastern direction). Using the holistic view learned from the nehiyawak medicine wheel helps us to understand and act on the teachings in the stories and, in the case of the story I chose, take action both individually and collectively in terms of environment and climate change adaptation and mitigation.

This story, the Birds of Colour: Part 2 tells how Blue Jay got its colour. This is an oral story told by my father, Micheal Sidney Lamouche, from Kapawe’no First Nation and transcribed over a series of meetings. He has collected many stories from different friends and family that live in Cree communities across Northern Alberta and has given me permission to use this story for this case study. Stories about Wesakechak, the nehiyawak trickster, often teach us about our actions and consequences, values, and how things came to be. Many Indigenous peoples use oral storytelling to pass on knowledge, history, and culture. In my nehiyaw culture storytelling was saved for the winter.

The story of the Birds of Colour: Part 2 demonstrates the power of Indigenous storytelling and how it can inform actions to improve Two-Eyed Seeing in climate research and policy discussions with story as the vehicle to drive transformational change. As described by Albert Marshall: “Two-Eyed Seeing refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing and to using both of these eyes together” (Bartlett et al. 2012).

Birds of Colour: Part 2

Wesakechak, hosted a contest to name the birds—the bird with the most beautiful colours would win. The birds found their colours from nature. One of the birds had difficulty choosing a colour. The bird flew around but could not decide since all of the colours were so beautiful and soon all the colours were taken. The bird went to Wesakechak and explained why he did not have a colour:

“It was love.”

Wesakechak said, “Little brother, remember sometimes you only have one chance to get, or do, something next time to remember—that if you want something go and get it, or it may never come again. Sometimes we have thoughts or feelings that we want to do something good, but we don’t remember that those thoughts and feelings were put there by our spirit guide.”

Once the birds had gathered, there were many colours. Wesakechak decided not to choose a winner as they were all special and had a different role in nature. In trying to help the bird find a colour, he asked a sparkly white bird how he got his colour. He replied it was from trying to fly over the mountain and getting caught in an avalanche. Wesakechak said:

“There are all kinds of colourful flowers on the other side of the mountains.”

The little bird was so excited it flew away, not waiting for Wesakechak to finish talking. As the bird flew towards the mountains it started to fly higher and when he was over the clouds, looked as far as he could see and only saw more mountains.”

The bird flew back towards the others, not realizing it had the colours of the sky—its chest was white and its back was blue. Wesakechak said it would be known as,

“the bird that carries the sky on its back. You will also be known as the bird that didn’t wait for all the instructions. So you have to learn patience and listen to all the instructions” (Lamouche 2021).

The spark within: Igniting the spirit to take action on climate change

In the nehiyawak medicine wheel we start in the eastern direction, where the sun rises. This is also associated with the element of fire (sun), childhood, the beginning of the day, and the spiritual aspect, which includes culture and identity. Culture and identity is foundational to how we live our lives and to our behaviours, actions, and values. It is often taught through story which might become a spark of inspiration and motivation or a fire within, igniting a passion. In other words, culture and identity is our why: “Those of us who are Indian understand that it is the telling of stories, our very breath, that brings forth identity and defines purpose” (Lucci-Cooper 2003). This is an important part of learning, “…we learn best when we feel a strong, inner spiritual connection with everything around us” (Anderson 2017). For many Indigenous people culture and identity is directly connected to the land on which we live, “to know yourself you must first know the earth” (Cajete 2000).

The story of the Birds of Colour: Part 2 is also centred on identity, one aspect of spirit. We see the birds with their own agency—choosing different colours so that they can be given names and an identity. This is an important aspect of Indigenous teachings—to foster self-determination—which is a stronger motivator for change than being told what to do (Lamouche 2022). We can apply the lessons from the story that we have our own agency to make choices, to motivate us to take action and make change where it is most needed and right now that is in relation to climate change. To address climate impacts we need to make a conscious choice to change individual and collective behaviours to make a real and lasting difference in the world. We can do that by drawing on our own agency and the part of our identity (the spiritual aspect of the medicine wheel) that is connected to better “knowing the earth”—only then can we take effective action on climate, based on that deep knowledge, connection to the land, and our motivation.

In many Indigenous cultures, language and connotation also matter in relation to identity. Indigenous stories often reference specific animals as non-human kin, by calling them simply by their name. For example, we will say “Blue Jay was flying” rather than “a blue jay was flying” which is what the western tradition would do. Another layer to this can be found in the way Blue Jay is at first referred to as “the bird” rather than “a bird”, further personifying him by giving him another layer of meaning and identification: In looking at the definition of “a” we can see that it is used before a singular noun, emphasizing the individual. By comparison “the” can be used for a singular noun but that noun should be understood generically (Miriam-Webster 2023). Rather than specifying an isolated individual animal, Indigenous storytellers’ preference emphasizes the whole, the group, or interconnectedness. This is an important spiritual understanding connected to nehiyawak identity and culture (the eastern part of the wheel). Embedded within how stories are told, even in English, we can see that the understanding of our relationships and fundamental interconnectedness with the animals, plants, and all of the natural world, are important in Indigenous worldviews. Including this deeper, fundamental understanding of the interconnectedness within the natural world—which we are a part of—in conversations about climate frameworks and policies could help guide their design and implementation so that their approach is more holistic.

When we see the bird hesitate and say, “It is love,” Wesakechak responds by explaining that the “inner knowing” or having a “feeling” are our spirit guides. This highlights the deeper listening and body senses as knowledge that is used in Indigenous ways of knowing and Native science (Cajete 2000). In terms of climate change policy this might lead to new understandings of the environment and the need for a more holistic and balanced view of climate change and the environment.

Embodiment, taking action, and transforming behaviour for climate action

We move around the nehiyawak medicine wheel in a clockwise direction, often referred to as following the movement of the sun. This brings us to the southern direction which is associated with the physical, youth, and the element of earth. It is related to our fitness, our body, and the environment. The physical is about movement, action, embodiment, and transforming our lives through changed behaviour.

In the story we see the importance of physical action when Wesakechak explains to the bird that sometimes we only get one chance to take action, highlighting the importance to sometimes act when we can. In relation to climate change we can think of this as a message to take action now—because now we have the chance, whereas in the future we may not. This also supports the idea of many Indigenous stories as “instructions for the future.” If we understand this story through this lens then we can clearly hear the message that taking action now is necessary in order to address climate change.

In this story different aspects of the environment—also part of the southern direction of the nehiyawak medicine wheel—are highlighted: the colours of birds, the sky, the plants and flowers, the images of the mountains, and the avalanche. We see the lesson of everything in nature having an important role and diversity of nature is emphasized. This can be seen as an instruction on how to be observant of the world around us, and that even if we don’t understand all the roles and meanings, to value all things in the natural world, including biodiversity. These teachings should be extended to climate policy to encourage decision makers to understand that we need to protect the biodiversity in the natural world, even if we don’t understand what part all beings and non-beings play in that world. A western approach often compartmentalizes in ways that are unhelpful—for example seeing biodiversity and climate issues as separate (Climate Atlas of Canada).

The physical environment also becomes a reminder of our body’s (also part of the southern direction of the wheel) relationship to and reliance on the natural world. When we understand this, suddenly the need to protect the physical environment takes on greater urgency. We see that it is about protecting ourselves and, looking at it through the lens of the nehiyawak medicine wheel, our families, communities, and nations. This is a different perspective than in western science which often looks at the physical world and solutions through silos and from an economic perspective (Cajete 2000). This deeper understanding can help shift our behaviour and the approach we take to policies and solutions to protect that world.

Connecting with the heart in order to care about climate

In the western direction on the nehiyawak medicine wheel is the stage of adulthood. It is characterized by responsibility, relationships, and emotional aspects. It is symbolized by the element of water, which is seen as healing: my Mom would say, our tears are healing, and the teachings also tell us this. Building relationships is an important aspect of nehiyawak wellness, worldviews, and knowledge. This is represented in the concentric circles of the nehiyawak medicine wheel. Unlike in western society, many Indigenous peoples do not see our lives as growing up in a linear, isolated, and individual way. Instead Indigenous cultures see lives as holistic and communal, fundamentally based on strong community relationships. This foundation also extends to developing respectful relationships with the natural world (Cajete 2000; Anderson 2017; Archibald 2008) a relationship that often differs from the one in a western worldview. It means that Indigenous Peoples have a different approach to caring for the environment and thus may have different ideas about effective solutions and actions related to climate change, an important factor in co-development of policy.

This story of Blue Jay has another teaching for us. For example, in the story, the bird went to Wesakechak and explained why he didn’t have a colour as he sees all colours as beautiful. Wesakechak says he can not choose a winner because all the colours are beautiful. From the perspective of the story this leads to the question of what would happen if all of us “see colour” in terms of race as a beautiful thing and something that reflects the diversity of nature. This would create a more respectful relationship amongst different races and cultures, and more respect and inclusion of various knowledge and perspectives. In terms of anti-racism, colour blindness towards other races is considered a microaggression (Reading 2020). Respecting the differences of others helps us to have healthy relationships. The story teaches that diversity is a valuable part of nature and should be protected in climate change policy discussions and implementation.

The story explains how the physical features of the birds and their different colours come from the natural environment, flowers, plants, snow, and sky. This helps to highlight the birds as connected to nature and seeing a relationship between all things is an important reminder in the story as it teaches us to form a deeper connection to, and in turn, want to care for, all of creation. After hearing the story, now when you see Blue Jay, you think of the blue sky, air, mountains, and sunny days, creating a deeper connection to and understanding of how interconnected the natural world is. This deeper emotional connection creates and encourages a respectful relationship to the natural world, one that is deeper and more expansive than in western science.

The wisdom of Elders to ensure stories continue in order to influence climate change

The mental aspect on the nehiyawak medicine wheel is represented by the northern direction and the Elder stage of life. The mental aspect includes knowledge, wisdom, thoughts, and the element of air. Stories and teachings combined with experience give Elders a depth of layered knowledge that they carry with them and when Elders pass their knowledge on to children (east) they help the circle of the good life continue and carry on through the generations. At the end of Blue Jay’s story we hear the lesson of patience and listening to instructions before acting. In a larger context we can see that storytelling and teachings play an essential role in guiding our actions and behaviour. It can remind us to listen to our Elders and highlight the importance of the stories, wisdom, and experience that Elders carry and how that wisdom can guide our own actions. It highlights the importance of listening to Elders as “the first line of teachers, facilitators, and guides in learning Native science” (Cajete 2000).

For example, when Elders use phrases such as “beaver was swimming” instead of “a beaver was swimming” it could be misinterpreted as being less “educated” or not “proper” English, rather than thinking of the deeper meaning of these phrases as stemming from a deeper worldview.

By being patient and listening to and respecting the expertise and learnings (or instructions) from the Elders, we ensure that valuable wisdom is not missed.

Seeing and knowing Blue Jay as the bird that carries the sky on its back changes the way we think. It reminds us of the story of the colours of birds and the teaching of patience, valuing all the different birds, listening to intuition, and taking action. These are teachings and reminders that can be valuable across a lifetime. As Elders share this wisdom they are ensuring the continued worldviews, instructions, and values that shape behaviours towards sustainability are passed on. The wisdom and experience of Elders can empower us and encourage us to think deeply about the world and move us to take action in terms of climate change and sustainability.

Conclusion

Indigenous people have been marginalized and excluded from climate change policy even though “Indigenous lands make up around 20% of the Earth’s territory, containing 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity—a sign Indigenous Peoples are the most effective stewards of the environment” (International Institute for Sustainable Development). Indigenous stories are connected to the land, and especially imbued with the values and worldviews that have sustained land, animals, plants, and people across Turtle Island (North America). The above examples of the deep and wide range of teachings in this single nehiyawak story show the vast amount of knowledge and expertise carried within Indigenous cultures and teachings, and how it can inform our approach to climate action and policy. These stories have been excluded and oppressed through colonization and European superiority rooted in racist ideology. This has been reinforced by western science and systems, including climate change conversations, and this exclusion means valuable lessons and perspectives are not being considered when climate actions and policies are implemented.

As nehiyawak stories demonstrate, Indigenous stories have inherent knowledge and lessons in them that can help us approach climate action, particularly as they help us to understand the interconnectedness of the natural world and our relationships to the land. The story of Blue Jay promotes responsibility, self-determination, and listening carefully to the wisdom of Elders. It teaches us about our interconnectedness and of our direct relationship to the land. When we have a closer relationship, based on respect and understanding through the teachings that the land and all that is in it are kin, we approach climate action with a deeper caring and understanding of the best approaches for all.

I have concluded with a list of policy recommendations for climate specialists in federal and provincial government to improve climate policy to be more holistic and understanding of Indigenous worldview including story, with the aim to advance reconciliation:

- Climate policy should be led by Indigenous Peoples and Nations (Reed et al. 2021) at the provincial and federal levels—this might include equitable co-creation of climate policies.

- Climate policy discourse should include storytellers, artists, spiritual Elders and cultural knowledge holders, as well as funding for them to share their work.

- In order for policy makers to begin to understand Indigenous worldview and work in co-development of policy and research with Indigenous peoples, public servants should be provided with anti-Indigenous racism training (Truth and Reconciliation Commissions of Canada 2017).

- Accessibility, protection, and generational transfer of the stories themselves through funding, programs for Indigenous artists and storytellers, as well as ensuring accessibility to the plants, animals, landmarks, cultural, and spiritual sites that carry these stories should be a policy priority.

- Indigenous traditional stories, teachings, and knowledge should be respected, accepted, and included in climate policy discussions without having to validate with western scientific studies.

- There should be funding for co-research between Indigenous and non-Indigenous climate researchers, artists, and storytellers.

- Funding to preserve and teach Indigenous languages should be provided, as they are necessary to understanding and interpreting stories as instructions for the future.

- Federal and provincial governments and policy makers should work with Indigenous nations to include Indigenous governance models and ways of doing as a framework (i.e., medicine wheel) to ensure a holistic perspective that incorporates Two-Eyed Seeing approaches in co-development of climate policy.

- An anti-Indigenous racism process should be applied to all sectors of Canadian society, especially policy decision makers at the provincial and federal level whose decisions impact Indigenous peoples and the land and waters in which our identity is inextricably connected to through story.

References

Anderson, Comay, and Chiarotto. 2017. A Resource for Educators. The Importance of Indigenous Perspectives in Children’s Environmental Inquiry. Ottawa, ON. https://www.naturalcuriosity.ca/englishbook

Archer, D. 2021. Anti-Racist Psychotherapy: Confronting Systemic Racism and Healing Racial Trauma. Montreal, QC. https://archertherapy.com/product/anti-racist-psychotherapy-confronting-systemic-racism-and-healing-racial-trauma/

Archibald, J. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit. Vancouver, BC. https://indigenousstorywork.com/

Bell, N. 2013. “Just do it: Anishinaabe Culture-Based Education.” University of British Columbia Dissertation 36(1). https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/CJNE/article/view/196553

Benton-Banai, E. 2010. The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway. Minneapolis, MN. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/the-mishomis-book

Cajete, G. 2000. Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Santa Fe, NM. https://tribalcollegejournal.org/native-science-natural-laws-interdependence/

Climate Atlas of Canada. 2022. Prairie Climate Centre. Winnipeg, MB. https://climateatlas.ca/

Ferguson, E. 2005. Einstein, Sacred Science, and Quantum Leaps: A Comparative Analysis of western Science, Native Science and Quantum Physics Paradigm. University of Lethbridge. Lethbridge, AB. https://opus.uleth.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/5082b74d-2475-4cad-9a92-1c64fa47afe3/content

Fontaine, F., Craft, A. 2016. A Knock on the Door: The Essential History of Residential Schools. Winnipeg, MB. https://uofmpress.ca/books/detail/a-knock-on-the-door

International Institute for Sustainable Development. 2022. “Indigenous Peoples: Defending an Environment for All: Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy.” https://www.iisd.org/articles/deep-dive/indigenous-peoples-defending-environment-all#:~:text=There%20are%20approximately%20370%20million,effective%20stewards%20of%20the%20environment.

Kendi, I.X. 2019. How to be an Anit-Racist. New York, NY. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/564299/how-to-be-an-antiracist-by-ibram-x-kendi/

Lamouche, M. S. 2021. “Birds of Colour: Part 2.” Transcription of traditional oral stories.

Lamouche, S.F. 2003. Ê-nitonahk Miyo-Pimatisiwin (Seeking the Good Life) Through Indigenous Dance. Peterborough, ON. https://digitalcollections.trentu.ca/objects/etd-1045

Lucci- Cooper, K. 2003. “To Carry the Fire Home.” Genocide of the Mind: New Native American Writing. New York, NY. https://iucat.iu.edu/iuk/5642365

Miriam-Webster. 2023. Dictionary. Springfield, MA.https://www.merriam-webster.com/

Mohammed, J., Anderson, P., Matthews, V. 2022. “Indigenous Peoples across the Globe are Uniquely Equipped to deal with the Climate Crisis – So why are we being left out of these conversations?” United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/indigenous-peoples-across-globe-are-uniquely-equipped-deal-climate-crisis-so-why-are-we-being

Murphy, J. 2007. The People Have Never Stopped Dancing: Native American Modern Dance Histories. Minneapolis, MN. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/the-people-have-never-stopped-dancing

Pelletier, C. 2018. “An Application of Two-Eyed Seeing: Indigenous Research Methods with Participatory Action Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1609406918812346

Reading, C. 2020. Social Determinants of Health: Understanding Racism. Prince George, BC. https://www.nccih.ca/docs/determinants/FS-Racism1-Understanding-Racism-EN.pdf

Reed, G., Gobby, J., Sinclair, R., Ivey, R., Matthews, D. 2021. Indigenizing Climate Policy in Canada: A Critical Examination of the Pan-Canadian Framework and the ZéN RoadMap, 12(3). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2021.644675/full

Solnit, R. 2023. If you win the popular imagination, you change the game: Why we need new stories on climate. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2023/jan/12/rebecca-solnit-climate-crisis-popular-imagination-why-we-need-new-stories

Wall Kimmerer, R. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN. https://milkweed.org/book/braiding-sweetgrass