Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

1. Introduction and context

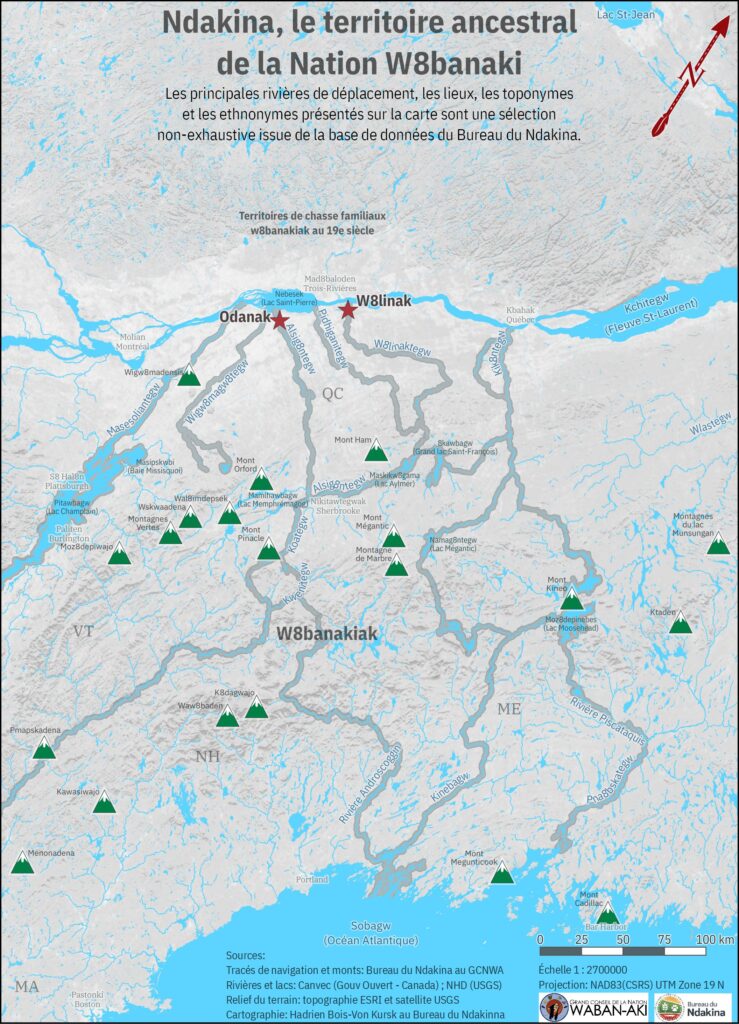

The Ndakina, the ancestral territory of the W8banaki 1 Nation, extends approximately from Akigwitegw (the Etchemin River) in the east to Massessoliantegw (the Richelieu River) in the west, and from the St. Lawrence River in the north to the Atlantic coast and the states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and part of Massachusetts in the south (see Figure 1). Currently, the Nation has more than 3,000 members in two communities, Odanak and Wôlinak. The Ndakina Office 2 works to safeguard the Ndakina in the long term, mainly via: 1) promoting and defending the Nation’s rights and interests on the Ndakina; 2) representing the Nation in territorial consultations and land claims; 3) documenting, preserving, showcasing and passing on the knowledge of the W8banakiak; and 4) supporting the Nation in fighting and adapting to climate change. To fulfill this mission, the Office favours an approach of territorial affirmation rather than comprehensive land claims.

The right of the W8banakiak to traditional activities, cultural continuity, and self‑determination is connected to territorial integrity. Research on modern use and occupation of the land conducted by the Office and for specific groups in the Nation (for example, youth or women) has clearly demonstrated this (see, for example, GCNWA, 2016). This research has also shown that human activities such as agricultural intensification, land privatization and the pressure exerted by commercial and sport practices have significant impacts on the Nation’s traditional activities (hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering, etc.), knowledge, health, and, ultimately, stewardship capacity. Despite these significant constraints and albeit with difficulty, the W8banakiak have been able to continue their ancestral activities over the years (Gill, 2003; Marchand, 2015).

To these pressures, climate change has now been added. The Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki launched projects focused on adapting to climate change in 2014–2015, based on an initial plan 3 (GCNWA, 2015).

As part of this initiative, members reported on how climate change is affecting the abundance, distribution, and health of species of wildlife, fish, and plants. One major effect is that, for many, the cycle and timing of hunting, trapping, and fishing have been disturbed; this varies between seasons but has intensified over the years. For example, hunters and trappers must stagger or sometimes cancel their activities. Winter travel has become more dangerous because of the fragility of the ice. Populations of some native species (for example, yellow perch) have dropped, and their meat may be of lower quality due to the proliferation of parasites that higher temperatures can bring. The quality and quantity of certain medicinal plants have also been negatively affected by higher temperatures, as when some medicinal plants dry out, they produce less essential oil. The proliferation of exotic invasive species is also an issue. Another major effect that many have observed is disrupted water flow and accelerated bank erosion, especially for Alsig8tegw (St. François River) and W8linaktegw (Bécancour River).

Overall, these changes have had major impacts on the way of life of many members of the Nation who practice sustenance, ritual, or social activities. The fact that these activities are vulnerable to climate change significantly reduces members’ cultural continuity and ability to transmit knowledge and practices, which ultimately impacts their health.

2. Assessing climate change adaptation initiatives

This case study is focused on two specific aspects of climate change adaptation initiatives: 1) project management, and 2) program governance and funding. What factors help a climate change adaptation project maximize its positive ecological and social impact, and what characteristics mean programs can help communities successfully adapt to a warming cliamte?

We find that the Ndakina Office has prioritized access to the land and cultural continuity through three projects to prevent and mitigate the degradation of biological and cultural resources: 1) Evaluating the reproduction success of lake sturgeon and restoring its habitat (2012–2018), 2) Evaluating the impact of climate change on the availability of medicinal plants and the proliferation of exotic invasive species in a health context (2018–2019), and 3) Evaluating erosion and flood risks on the banks of Alsig8tegw (St. Francis River) and W8linaktegw (Bécancour River)] (better known as the Erosion Project, 2019–present). These three examples were selected because they identified similar vulnerability factors and have taken similar approaches to community engagement.

3. The three cases

3.1. Management of species of cultural importance: lake sturgeon

The W8banaki Nation continues to have an important cultural connection with the lake sturgeon4 (the emblem of the Odanak community) and in particular the populations of the St. Lawrence River and its watersheds. The fish remains part of the Nation’s diet, and is especially prized as a dish for community gatherings. For 10 years now, the Odanak Land and Environment Office5 (known by its French acronym BETO) has conducted in‑depth documentation of the reproduction of the lake sturgeon in the St. Francis River, near the Drummondville hydroelectric dam where there is a spawning ground, with a view to proposing avenues for conservation efforts. The resulting research has shown that poor water flow management by hydroelectric stations has a negative influence on the sturgeon’s reproductive ecology, particularly during periods of migration and spawning (Dufour-Pelletier et al., 2021; see also Clément-Robert et al., 2016). Extreme weather events such as droughts, floods or heavy total precipitation further threaten the reproduction and long‑term survival of lake sturgeon in the area (COSEWIC, 2017).

In this context, BETO’s initiatives to monitor lake sturgeon reproduction and recovery have had a significant impact. Site management and water flow management plans have been recently set up, as has a sanctuary area where sport fishing is prohibited before the spawning season. These efforts were made in partnership with major regional actors such as Hydro‑Québec and the Minister of Forests, Wildlife, and Parks. Such protection and management measures are a hopeful sign for the species’ reproductive success and survival rate in the future. On the technical side, the BETO has developed advanced monitoring and management techniques. In a meeting, the project manager strenuously insisted that testimonials from certain W8banakiak fishers and knowledge holders were important for identifying and characterizing research sites of interest for initial work, planning and following up.6 In this sense, the efforts regarding the lake sturgeon are an excellent example of the integration of W8banakiak knowledge with western science. On the socio‑economic side, the long‑term project meant that a good dozen W8banakiak could be hired and trained, deepening the cultural ties between members and this emblematic species (see Photo 1). Furthermore, in material and financial terms, the funds generated helped to consolidate and grow the BETO, increasing its credibility and legitimacy with other regional actors.

3.2. Managing medicinal plants and exotic invasive species

In various studies, members have consistently stated that the intensification of climate change is disrupting the distribution and quality of plant species in southern Quebec. This disruption includes the proliferation of certain invasive species (for example, common reed and Japanese knotweed), which compete with valued species such as cattails or yarrow (GCNWA, 2015, 2016). Climate change also lowers the quality of important indigenous plants, as global warming leads them to dry out more quickly. These problems are of significant concern. At issue is not just a resource, but also members’ capacity to transmit knowledge and educate future generations. This is all the more concerning given that the W8banakiak have suffered the disruption of their ethnobotanical knowledge due to the colonial past and divisions between generations that they experienced; despite these challenges, interest in this knowledge and these practices continues (GCNWA, 2016).7 The project had two objectives regarding these issues: 1) to document and promote the availability and variety of medicinal plants in communities in a time of climate change, and 2) to promote the transmission of knowledge about medicinal plants, traditional medicine, and climate change.

The project promoted intergenerational ties by directly connecting Elders with younger people, which led the younger participants to develop a strong interest in traditional medicine.

The project had several positive outcomes. Interviews with knowledge holders gave researchers a better understanding of their perceptions of climate change’s impact on medicinal plants and ethnobotanical knowledge. A transect inventory method developed by the BETO, the BETW, and knowledge holder Michel Durand Nolett, used especially in wetlands and forested areas, helped provide more in‑depth data on the zones prioritized by the two communities and on plant species of seasonal interest. Vulnerable areas were identified by cross‑referencing the distribution of plant species of interest with that of EIS. The study also had a capacity‑building and awareness‑raising component: knowledge holders led sharing workshops, a community garden was set up, a booklet and videos on medicinal plants were developed, along with other efforts to raise awareness of EIS‑related issues (see Photo 2). The project promoted intergenerational ties by directly connecting Elders with younger people, which led the younger participants to develop a strong interest in traditional medicine. For example, a young Abenaki woman working at the BETO has now been approached about taking over the transmission of such knowledge about ancestral plants.

3.3. Assessing erosion and flood risks in the context of climate change

Water systems have always been dwelling places for the W8banakiak. Alsig8tegw (the St. Francis River) and W8linategw (the Bécancour River) are key witnesses of the Nation’s presence in Quebec, first semi‑permanent and then permanent. Many locations along the banks of these rivers have been recognized as important places of occupation and registered by Quebec’s Minister of Culture and Communications. Oral and written sources and settlement patterns have also identified other sites of great potential interest (for example, portages, campsites, ceremonial sites or burial sites). Today, many W8banakiak still practice activities on the same rivers, including hunting, fishing and gathering. However, climate change is accelerating erosion along Alsig8tegw and W8linategw (Roy and Boyer, 2011; Tremblay, 2012). Members confirmed this trend in interviews conducted for the climate change adaptation plan (GCNWA, 2015). Erosion and sedimentation can have major impacts on water quality and fish habitats, and therefore fishing. They can also damage important archaeological and cultural sites.8 The first phase of the project to assess erosion and flood risks along the banks of the rivers Alsig8tegw and W8linaktegw in the context of climate change established the extent of the degradation and documented its impact on the archaeological and cultural heritage of the region.

From this work, observation and recorded data have tracked erosion mechanisms in dozens of zones with archaeological or cultural potential, the implementation of erosion vulnerability indices, and the creation of tracking sheets (see Photos 3 and 4). This risk assessment should help the Nation to better plan and manage the efforts needed to mitigate erosion impacts and protect these sites. As in the lake sturgeon monitoring project, some W8banakiak recognized for their knowledge of navigation were consulted to help researchers understand the history of, and changes in, the hydromorphology and ecology of the two rivers. Beyond archaeological considerations, one field employee reported that the project allowed them to explore the territory in greater detail than usual, because of the study’s intersections between biophysical features and topological features. This work helped to build the capacity of the archaeology and biology teams and opened the door to developing joint projects. Once again, BETO and BETW participation in this project and its fieldwork activities provided jobs to members of the Nation.

4. Lessons learned and best practices

4.1. Lessons learned for climate change adaptation advance planning

As stated above, the GCNWA launched its climate change and adaptation efforts with the help of a provincial program to support the creation of climate change adaptation plans. Since the funding was short‑term (one year, after a long approval period), the program excluded all implementation activities, preventing any application of a longer‑term and more promising vision.9 Members of the Ndakina office and the BETO and BETW pointed out many other gaps as well, including the limited scope of the consultation and the top‑down plan implementation approach that involved excessively close monitoring of the process and delays in execution. The result of this process was a rigid and standardized plan. It was difficult to integrate members’ key concerns, such as traditional Indigenous knowledge, which was dismissed in favour of measurements and quantification. (For example, little consideration was given to observation of ice or snow.) In retrospect, the focus on exhaustive data collection, analysis, and written reporting was deemed to be distant from members’ more concrete and practical priorities.

In response to this institutional context, and although the climate change adaptation plan provided significant information and orientations that directly led to some climate change adaptation projects, the Ndakina Office, the BETO, and the BETW launched an adaptation program that was more closely aligned with the priorities that members had expressed in various consultations on the use and occupation of the land, working with the opportunities available at the time. This is a more bottom‑up approach to planning.

4.2. Lessons learned for managing climate change adaptation projects

In our experience, when developing projects, it is important to take into account ecological, social and cultural dimensions and the Nation’s interests for the Ndakina. Good starting hypotheses for research work and correct diagnosis also require appropriate mobilization of scientific and traditional knowledge. The participation of knowledge holders and members (particularly Elders and youth) as advisors and for validation is especially useful for achieving this. Greater involvement of the Nation’s members and elected leaders remains a constant challenge. We have observed that they will get involved more directly in projects that provide them with tangible benefits (for example, jobs or salaries, access to equipment, or training or learning opportunities).

On a broader scale, we have seen that strong collaboration between the Nation’s administrative units and regional actors has allowed for a deeper analysis of issues and for more ambitious initiatives. In the two sections that follow, we will see that additional factors, such as the institutional and financial context, may be catalysts or obstacles for projects.

4.3. Lessons learned for climate change adaptation governance and funding

A project’s success depends greatly on the source and nature of its funding. The issue here lies in defining what “high‑quality” funding means for First Nations communities. The experiences of the three projects presented here show that quality funding must be sufficient, stable, flexible, available in cash and in kind, and tailored to community needs.10 Obviously, the volume, stability and long‑term continuity of funding help to ensure greater autonomy in planning and implementing climate change adaptation. For example, wildlife management and inventory work for the lake sturgeon predate the climate change adaptation plan and benefit from substantial multi‑year funding from the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk that allows for consistent program‑related decision making. This continuity of funding makes it possible to plan long‑term activities and thus maximize their impact. It is no less important, however, to obtain more ad hoc funding, given that the land and environment offices are small organizations. Such funding allows them to round out work teams, provide competitive wages to members of the Nation, and invest in up‑to‑date equipment.

In all three cases, feedback emphasized the value of funders leaving a certain amount of flexibility to project heads, resulting in greater independence in articulating the project and its orientations. Of the three projects, two were nearly not funded because they did not match the initial scope of the programs. For the project on medicinal plants done in collaboration with Indigenous Services Canada and Health Canada, it was necessary to negotiate the project’s eligibility before funding was obtained, which pushed back the approval and start‑up phases. The Erosion Project ran into similar difficulties. The Department of Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs deemed work with an archaeological component to be ineligible for funding. The application was refused at first, but accepted after discussion and negotiation of the program’s scope.

A certain degree of independence is not the same thing as carte blanche. The Ndakina Office administrators we met with recognized the value of effective follow‑up. They appreciated when funders went beyond their administrative role to provide technical contributions as well. Another aspect of follow‑up they mentioned was the need to distinguish between the importance of ensuring project compliance (for expenses or deadlines, for example) and the importance of providing opportunities to exchange information and learn, especially between project leaders and the funder and between different communities funded (Indigenous and non‑Indigenous). Certain GCNWA‑led projects have a strong potential for being duplicated in or transferred to other communities or contexts, particularly innovative projects and those that were notably successful. Similarly, the Ndakina Office considers that, in current funding programs, the component for the community of practice to learn and share results is a poor relation of sorts, and that platforms showcasing successful Indigenous projects are extremely rare if not non‑existent.

In our experience, available funding must be designed in a specific or targeted manner for Indigenous communities (or, more broadly, for small rural communities). Otherwise, it is difficult for small administrative bodies like the Ndakina Office or the BETO/BETW to submit competitive applications. One possible solution would be to strengthen an association’s connections with regional organizations that have compatible visions and goals (for example, watershed organizations for the Erosion Project), to enable small organizations to seek more substantial funding. Other potential allies include major programs working to protect at‑risk species (such as the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk or the Quebec Wildlife Foundation), that set regional priorities each year. However, the species of cultural priority to the Nation (moose, lynx, yellow perch, lake sturgeon, etc.) rarely appear in those lists.11

The Nation’s sovereignty is negatively affected by this exclusion of key species from at-risk status. We believe that each nation must be able to define their own priority species for funding, but current federal mechanisms do not allow for such flexibility. This issue highlights the necessity of understanding the needs and priorities of each community and its organizations, so that proposed projects can be tailored to the local context and desires.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The integrity of the Ndakina is critical for the W8banakiak to effectively exercise their rights regarding self‑determination and the practice of traditional activities. Over the last few years in particular, members have shared their growing concerns about the impact of climate change on these rights (hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering, etc.). Climate change affects both the quality and the quantity of species of wildlife, fish, and plants. Such resources also have a high cultural value, so the fact that these activities are vulnerable to climate change also reduces the Nation’s ability to transmit its culture between generations. The climate change adaptation‑related planning and three cases presented here have helped to highlight these concerns and impacts. The concrete outcomes of the three projects include deeper BETO and BETW expertise on the socioecology of the Ndakina, connecting traditional Indigenous knowledge and modern science; greater technical and material skills; tangible benefits for members and knowledge holders; closer collaboration among members, administrative units, and a variety of regional partners; and stronger intergenerational ties to strengthen a culture of territorial stewardship in youth.

The factors that contributed to the three projects’ success in planning, funding, and execution have led us to make the following recommendations.

Community-engagement recommendations:

- Encourage research by communities. This allows them to mobilize their members, suggest good diagnostic measures, and set up efforts that are relevant to the community’s situation.

- Promote participatory approaches to interventions that include Indigenous knowledge and modern science, and consider socio‑economic benefits (wages, building technical capacities) as central elements of participation and inclusion.

- Encourage opportunities for networking in a spirit of collaboration between First Nations and regional actors whose missions and activities are often complementary with regard to sustainable environmental management.

Planning and funding recommendations:

- For climate change adaptation plans (an essential tool for conceptualizing the issues, objectives, efforts and key stakeholders to involve), consult with members widely and in an ongoing way, and ensure that the planning framework comes from the community rather than following a template.

- Provide Indigenous communities with recurring core funding so that they can both fight, and adapt to, climate change.

- Ensure that funding for climate change adaptation programs is more flexible and able to accommodate cultural, spiritual and other dimensions, to fit the more holistic First Nations understanding of the land.

- Adapt funding in certain sub‑sectors (such as species conservation) to communities’ specific needs and priorities.

- Ensure that funding options open the door to more technical support and to opportunities for learning and discussion among participating First Nations.

The W8banaki Nation is currently updating its previous climate change adaptation plan, which covered 2015–2020. We have learned a great deal from the adaptation projects carried out in the last few years, and have every hope that this plan will take a queue from more inclusive planning processes so that we can work to successfully ensure the long‑term integrity of the territory needed for the Nation’s cultural continuity and self‑determination.

About the authors

Rémy Chhem is Environmental Project Manager at the Ndakina Office and is currently completing a Ph.D. in international development at the University of Ottawa.

A member of the W8banaki Nation, Suzie O’Bomsawin has worked as Director of the Ndakina Office of the Grand Council of the Waban-Aki Nation since 2013. A resident of the Odanak community, she is also very involved in various organizations dedicated to the interests of First Nations.

Jean-François Provencher is Executive Assistant at the Ndakina Office, and holds a master’s degree in environmental management from the Université de Sherbrooke.

Samuel Dufour‑Pelletier is a biologist and Director of the Bureau environnement et terre d’Odanak.

References

Ndakina Office. (2020). Projet de recherche sur l’impact des changements climatiques sur la disponibilité des plantes médicinales et la prolifération d’espèces exotiques envahissantes pour les communautés d’Odanak et de Wôlinak dans un contexte de santé. Wôlinak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Clément-Robert, G., S. Gingras, M. Pellerin and R. Poirier. (2016). Enquête sur les sources de variation de débits de la rivière Saint-François durant la période de fraie de l’esturgeon jaune. Sherbrooke: Université de Sherbrooke.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). (2017[2006]). Assessment and Update Status Report on the Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in Canada. Ottawa: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, 124 p.

Dufour-Pelletier, Samuel, Émilie Paquin, Philippe Brodeur and Michel La Haye. (2021). “Reproduction de l’esturgeon jaune dans la rivière Saint-François : un exemple de participation des peuples autochtones à la conservation d’une espèce emblématique.” Le naturaliste canadien.

Dumont, P., Y. Mailhot and N. Vachon. (2013). Révision du plan de gestion de la pêche commerciale de l’esturgeon jaune dans le fleuve Saint-Laurent. Québec: Ministère des Ressources naturelles du Québec, 127 p.

Gill, Lucie. (2003). “La nation abénaquise et la question territoriale.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 33(2), p. 71–74.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2015). Plan d’adaptation aux changements climatiques – 2015. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2016). Étude de l’utilisation et de l’occupation du territoire de la Nation W8banaki, le Ndakina, et des connaissances écologiques traditionnelles qui lui sont associées dans la zone d’influence du projet d’oléoduc Énergie-Est de Transcanada. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2021). Évaluation des risques d’érosion et d’inondation sur les berges des rivières Alsig8ntekw (Saint-François) et W8linatekw (Bécancour) dans un contexte de changements climatiques. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Marchand, Mario. (2015). Le Ndakinna de la nation W8banaki au Québec : document synthèse relatif aux limites territoriales. Wôlinak: Ndakina Office, Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Nolett Durand, Michel. (2008). Plantes du soleil levant Waban Aki : recettes ancestrales de plantes médicinales. Odanak.

Roy, A., and C. Boyer. (2011). Impact des changements climatiques sur les tributaires du Saint-Laurent. Presentation at the Colloque en agroclimatologie of the Quebec Reference Centre for Agriculture and Agri‑food (CRAAQ), Université de Montréal.

Tremblay, M. (2012). Caractérisation de la dynamique des berges de deux tributaires contrastés du Saint-Laurent : le cas des rivières Batiscan et Saint-François. Master’s thesis in geography, Université de Montréal.

Treyvaud, Geneviève, Suzie O’Bomsawin and David Bernard. (2018). “L’expertise archéologique au sein des processus de gestion et d’affirmation territoriale du Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 48(3), p. 81–90.

- W8ban means “dawn” and Aki means “land.” W8banaki, then, means “the People of the East or of the dawn.”

- In 1979, the Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki (GCNWA) was mandated by the Councils of the Abenaki bands of Odanak and Wôlinak to act as an administrative body to meet the needs of the two communities. In 2013, the Ndakina Office of the GCNWA was created to respond to the growing number of territorial consultations.

- The initial spark was a Green Fund pilot program, jointly administered by the Minister of the Environment and the Fight Against Climate Change and the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Sustainable Development Institute. The plan provided an initial overview of the climate change effects that had been observed in the Ndakina, and the priority risks and vulnerability factors of the two communities (GCNWA, 2015). The plan also proposed options for risk management and adaptation measures.

- Note that the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has recommended that the lake sturgeon be given threatened species status (COSEWIC, 2006). The lake sturgeon is also likely to be designated a threatened or vulnerable species at the provincial level. Commercial fishing management measures instituted in 1987 and breeding habitat improvement efforts have helped the species recover. Still, the most recent management plan for lake sturgeon in the St. Lawrence River recommends ongoing research and conservation efforts and, where needed, improvement of spawning areas throughout the St. Lawrence River system (Dumont et al., 2013).

- Since 2007, the Odanak and Wôlinak land and environment offices (BETO and BETW) have been working on a number of environmental projects. Over the years, they have developed wide‑ranging expertise, particularly in the arena of climate change. One of the offices’ key mandates, in collaboration with the NO, is to improve understanding of the Ndakina (wildlife, plant life, water, land, etc.). They use concrete, well‑defined projects to play a part in the sustainable management of at‑risk species and habitats, through knowledge acquisition, habitat enhancement and ecological monitoring efforts carried out in parallel with a variety of community activities (such as awareness raising and knowledge transfer).

- A knowledge holder is a member of the Nation who has a particular connection with the Ndakina for food, ritual, cultural or social purposes. This connection could involve hunting, fishing, trapping, collecting supplies or navigation (travel and portage routes), or a deep knowledge of practices such as songs, dances, ceremonies, legends and storytelling, language and place names. Knowledge holder status is not necessarily synonymous with Elder status, but refers primarily to members who are recognized by their peers as a go‑to reference to consult. Knowledge holders are consulted at different points in a project (conceptualization, initial work, verification) and in different ways depending on the process: word of mouth, individual conversations or interviews, group discussions, activities in the field, etc.

- A survey conducted as part of the Ndakina project (2016) showed that approximately 15 per cent of W8banakiak regularly practice ethnobotany for medicinal, cultural, or dietary purposes, and that 50 per cent have traditional knowledge of plants, without any major divergence between men and women.

- Bank erosion is a natural phenomenon that has amplified significantly with the anthropization of the region and with climate change, threatening the archaeological heritage of the Ndakina. Global warming leads to a process of degradation of riparian zones that destroys archaeological sites. An archaeological site exposed by erosion may vanish for good within a few months (GCNWA, 2021).

- Furthermore, when taking part in the COP21 in Paris in 2015, the director of the Ndakina Office expressed reservations about Quebec’s leadership, both in terms of its lack of long‑term vision and its insufficient funding for local communities.

- It was also mentioned that the “cost of entry” is high, i.e., that the complexity of the forms and schedules required for funding can discourage applications. While it is important to have complete files with as much detail as possible (to justify the work plan and ensure follow‑up), it was suggested that the application requirements be tailored to the applicant’s experience level.

- Yellow perch has never appeared on either the federal list of species at risk or the provincial list of threatened and vulnerable species. It has been a target for funding since 2018, but only for the Quebec Wildlife Foundation. Lake sturgeon was a priority for AFSAR until 2017, as the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada had declared it a threatened species.