Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series of Indigenous-led climate research, produced in co-operation with the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources.

Natasha Akiwenzie from Lac Seul First Nation and Andrew Akiwenzie from the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation have been observing the impacts of climate change and colonial practices for a long time. In 2018, they closed their commercial fishing business located in Neyaashiinigmiing, Ontario, in response to a number of climate change-related setbacks and challenges, and instead started an environmental not for profit corporation, the Bagida’waad Alliance. The goals of the organization are to research and educate how climate change is affecting the waters and environment of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, to encourage the community’s youth to document the stories of the Elders, and to promote more active stewardship of the lands and waters.

This case study uses the method of Indigenous autoethnography or storytelling, which aims to address issues of social justice and encourage social change by engaging Indigenous researchers in rediscovering their own voices as “culturally liberating human-beings” (Whitinui 2013). Traditionally, in Anishinaabe communities, knowledge is transferred through the telling of stories, often around a fire or while sharing food, so the heart of this autoethnography is the story of Natasha Akiwenzie as she tells it, situated within a broader context of the impacts of climate change in the Great Lakes region. You can hear her passion in the story directly, as well as read about the context of her family’s story and how climate change affected their Anishinaabe fishery. The conclusion includes calls to climate action as well as recommendations for various groups of people from the international to the local level.

Historical and cultural context

The Saugeen Ojibway Nation consists of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation and the Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation. The two reserve communities are situated approximately 60 kilometres apart on the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula, with Saugeen located at the southwestern corner of the peninsula and Nawash about an hour away on the Georgian Bay side. When working together on matters of mutual interest, they are collectively identified as the Saugeen Ojibway Nation, with a total on-reserve population of approximately 1,500 people. The Saugeen Ojibway People have engaged in fishing activities in their traditional territory for food, ceremony, and trade from time immemorial, and have actively retained their fishing rights around Saukiing Anishinaabekiing. Moreover, the health and viability of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation, their places of cultural and spiritual significance, and their economic opportunities are linked to the health of the lands and waters of their traditional territory, Saukiing Anishinaabekiing, which includes the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula and its surrounding waters.

Natasha Akiwenzie’s story: The beginning

In 2003, my husband and I started a small-scale commercial fishing business, fishing for lake whitefish and lake trout in the waters of Georgian Bay, and selling our catch at local and regional farmers’ markets. While our business grew quickly over the years, we also noticed that higher winds and severe storms were making it increasingly difficult and dangerous to get out on the water, and warming water temperatures and declining winter ice cover on the lake were negatively impacting ecology and fish populations. In 2018, we made the difficult decision to close our commercial fishing business and establish the Bagida’waad Alliance, a registered not-for-profit corporation with the goals of promoting research and education about the impacts of climate change on the waters and environment of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, encouraging our youth to document the stories of the Elders, and promoting more active stewardship of the lands and waters.

Before we get too far along, I would like to share my first experience fishing. My husband was fishing for another person but they couldn’t make it that day. I thought I could maybe help, even though I had never gone fishing before. I remember sitting at the bow of the boat and taking in all the beauty that surrounded us. The water was clear and lapping gently against the boat. We were headed to the first net and I noticed how calm and relaxed Andrew looked. We got to the first net and Andrew said I should just sit put and help get the fish out of the nets. I realized just then I had no idea what I was about to do. He started pulling the lines and eventually the net appeared. Soon after that a fish appeared. A giant fish. Andrew laughed because he said it was about six pounds. He said it was a whitefish. Then another fish came up and again it was a whitefish. Andrew had taken fish out of the net and placed them in the fish box in front of me, but the fish were still moving. I picked up the smaller one and slid it up and overboard. I realized Andrew had stopped lifting the net. He said I couldn’t release all the fish. He would tell me when we could toss it overboard. A sucker came in and that one I could toss overboard. Then an eelpout came in and it peed on me. Luckily that could go out too. A beautiful, large fish came in next. I was impressed. Andrew had me try to get it out of the net. I was trying to get the net over its massive head but all of a sudden it opened its mouth and chomped on the skin between my thumb and my index finger. Luckily, I had gloves on so it just gave me a good scrape. I learnt that it was a lake trout. After that bite, I had no issues keeping the fish in the fish box.

Over the years we continued to grow our business. In 2006, we received a business grant that allowed us to purchase a 24-foot long punt with an outboard motor and some new gill nets. The next year, we received the same funding and purchased long stainless-steel tables, commercial sinks, fish boxes, and an ice flaking machine to set up our own fish processing facility. Andrew’s grandmother’s house next door to our own had been empty for a while and we made the decision to use that space to process our fish. In 2009, we faced the challenge of having to bring it up to the provincial inspection standards for fish processing plants. That meant sloped floors, floor drains, all new electrical, plastic walls, bedrooms removed and made into storage areas, and hand washing stations. It was completed by the second week in September. We didn’t realize at the time we were one of the very few or possibly the only Indigenous owned provincially inspected fish plants in southern Ontario.

After initially selling our fish to wholesalers in Wiarton, we shifted to selling fish directly to customers from our home in Neyaashiinigmiing, and eventually in regional farmers’ markets. All of this was new to us. I remember the first market in Owen Sound and I was so nervous. Our young boys joined us. They were seven, six, and four years of age. We had put out samples of our smoked fish and our boys were busy handing out business cards. The fish was leaving the table. We were making some money, about as much as what Andrew would have made if he had sold it to the wholesaler. We kept returning to the market every Saturday and we kept coming home with less and less fish and more and more customers returning. But there were some difficult times, too. There were a few times I remember when people would walk by and ask us, “Native caught fish?” We would answer yes proudly but their response would take some of the wind out of our sails. They sometimes would respond with, “I don’t buy Native fish.” I had felt racism before but it was hard in a public setting and trying to be professional. Overall, most of the customers were wonderful and we learned to just smile and wish them a great day.

Demand for our product continued to grow. By the end of 2007 we were selling our fish at three Toronto markets: Riverdale, Dufferin Grove, and Brickworks. Andrew did most of the markets, and we were able to hire an employee to help process the fish. I stayed at home so that I could smoke the fish for the next market and care for our boys. Andrew fished on the days when he was home. It was such a busy time, but it was rewarding because we knew we were providing food to over 600 families a week. In 2008 we were invited by Slow Food Toronto to go with a group of other market vendors, chefs, and journalists to Terra Madra Salone del Gusto which is an international food festival in Turin, Italy, and we jumped on this opportunity. It was amazing to see all the food from all over the world in one location. By 2016, we were selling our product at two major Toronto markets, including the Wychwood Market and the St. Lawrence Market. Customers were attracted to the fact that we caught and sold local or native fish species from the Great Lakes, that our fish was wild-caught rather than farmed, and that we caught, processed, smoked and sold our own fish.

The fog moving in

Although our business continued to grow, over the years we continued to observe and experience environmental changes that made fishing ever-more difficult. One of the first changes we noticed was the amount of zebra mussels we were coming across. (Zebra mussels are an invasive species in the Great Lakes that do a great deal of damage by filtering plankton out of the water, starving native fish species of a key food source.) Andrew would need to smack his net against the hull of the boat so the zebra mussel clumps would fall off the nets and drift back to the bottom of the bay.

With zebra mussels disrupting the ecosystem of the bay, another related change we experienced was the amount of algae. As algae became more prevalent, it became more and more difficult for us to clean our nets. We couldn’t leave the algae on the nets because it added extra weight and the fish could see the nets. At times the nets were so thick with algae, they became difficult to lift out of the water. By 2010, our employees would have to clean the nets for a couple of hours at the end of their shifts just so that Andrew would have clean nets the next time he was out.

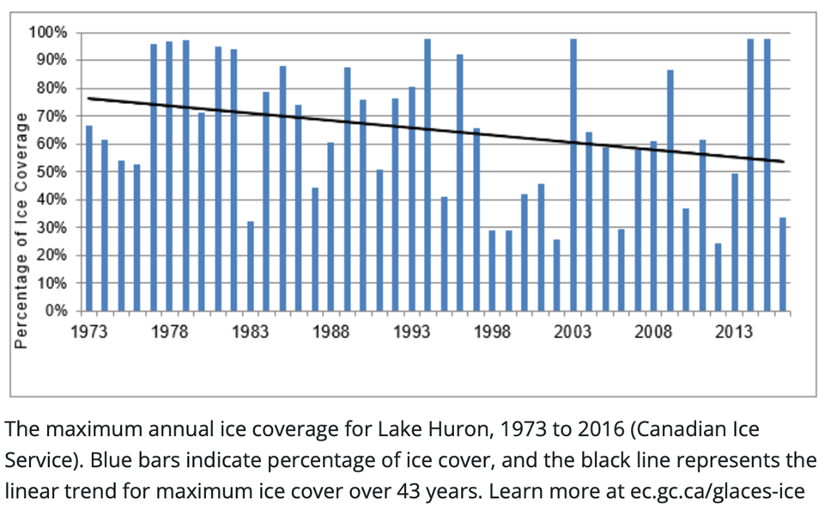

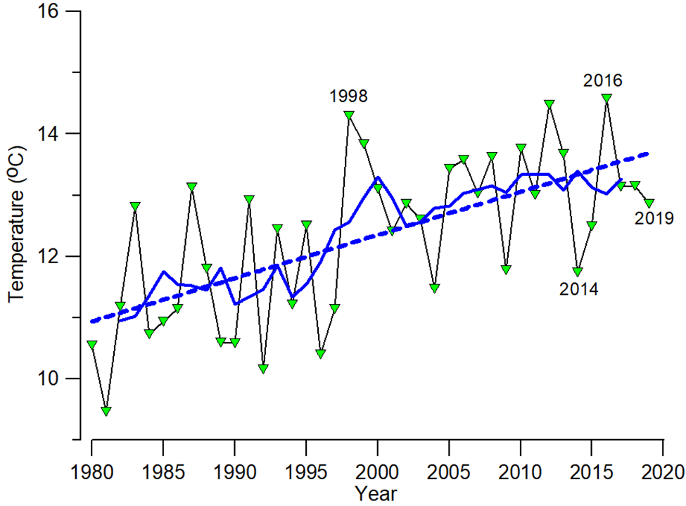

Over the years we have also noticed a warming of the waters, and declining ice cover on the lake in the winters. Spring 2010 came and it was one of the first years I can really remember not seeing any ice during the winter. Andrew was able to return to fishing by around mid-March, which was great, for we had nearly run out of frozen fish.

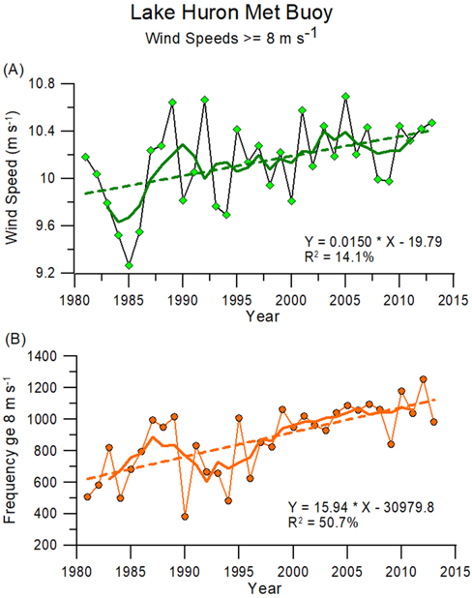

Stronger winds were also becoming more common. More strong wind warnings were being posted on the marine forecast webpage. Then every so often a gale warning would be posted. These winds not only threatened whitefish eggs and larvae, but made it much more dangerous for fishermen to be on the water as well. The days of ten-knot winds were getting further and further apart. I had only had to do the worried walk to the shore to look for the boat a handful of times before, but that worried walk was becoming more frequent. A lot of the time I would still be trying to wake up and Andrew would already be out on the water. I could hear the wind and I could see the trees swaying. I would take a deep breath because I knew I had to just keep an eye on the time and try not to worry. I am not sure if he knew how relieved I was on the really breezy mornings when I would go next door and he would be standing in the driveway.

The foggy mornings, by contrast, always brought a stillness with them. When I saw the fog slowly blanketing the land and moving across the water I always felt relieved. When there is fog, the winds are calm.

By the fall/winter of 2014, we realized we were in trouble. Over the summer we had dealt with a lot of windy days and had to cancel a lot of markets. That fall we endured strong wind warning after strong wind warning, with an occasional gale warning. Andrew needed two days back-to-back to fish—one day to set the nets and the next day to lift. I needed enough fish to turn on the smokers three days before a market. We puttered around on shore, just hoping for the winds to give it a break for a bit. They did once every couple of weeks but not long enough to put anything away for the winter.

Through 2015-16, weather issues continued to challenge us. We had a lot more time on shore, and when we did fish there were a lot of challenges with algae or trying to sneak out early, before the wind picked up.

We were also noticing a significant change in the quantity and composition of our catch. When we first started fishing we would catch about 24-32 whitefish and four to six lake trout nearly every lift. By 2012, Andrew was still catching about the same number of fish but it was becoming more lake trout—like 22-28 lake trout to six to ten whitefish. The lake trout were also mostly small, about three pounds. We actually needed to create a new product to deal with the small fish, for we don’t believe in wasting what is given to us. We would filet the small lake trout, smoke them and then crumble them into small pieces and call them smoky bits. Our customers loved it but we were quietly concerned. By 2018, our catches were becoming more and more odd, with lake whitefish now only one to three fish per catch and lake trout up to 18-26.

Pea soup fog

We had the conversation every Saturday—why we couldn’t find the whitefish and why the winds were increasing. We would tell people about the ice coverage and how the young whitefish need it. We would tell them that with climate change, winds and storms will increase, which fishers see and feel first-hand. We would tell them about how the temperature of the bay was increasing and how that was changing the quality of the fish. People would listen, but sadly, a lot of them just worried about their alternate plan for dinner, now that whitefish was off the table.

In 2018, we looked at the fish in the freezer and realized we only had enough fish to do one more market. We needed to make some tough decisions. We decided that would be our last market and we would leave the business. We had agreed years earlier that if we ever felt the fish were in trouble, we would stop because we didn’t want to be the fisher to pull the last fish out of Georgian Bay. But we never thought we would see that day in our lifetime or our boys’ lifetime.

With these heavy decisions, I felt like I was out on the water as the fog enveloped the boat. I had to believe things were going to clear even though I was going into a future that was unknown.

We had to face the fact that the decline of the whitefish and the changing climate were beyond our control. That we couldn’t fix it alone. That was one of the most difficult days we ever had. Not only were we leaving a way of life; we were also leaving our market community, our fellow vendors, and customers we had known for a very long time. They had watched our boys grow up.

Making it to shore: Forming the Bagida’waad Alliance

In December 2017, a grant application from the federal government was forwarded to me. The fund was called the Indigenous Community-Based Climate Monitoring Program. I spoke with Andrew about the funding. We thought it would be good to apply for a weather station and a wind sock. There was a section in the application that asked us to summarize how climate change was affecting the community. I could see how it was changing the waters with the temperature increasing and lack of ice coverage in the winter but I needed to find someone who could help me with the land-based point of view.

A friend connected me to someone in Bruce County who was known for doing environmental work. I reached out to a woman named Victoria Serda, who was living in Port Elgin at the time. I really had no other goals with this call other than to complete the application and then submit it. We did submit the application—Victoria had walked me through my first federal grant.

After a number of lengthy discussions between Victoria, Andrew, and myself, we decided to form an environmental not-for-profit group. We formed a Board of Directors comprised of Indigenous fishermen, environmentalists, scientists, and youth, who are all part of my support team. The majority of the Board are Saugeen Ojibway Nation members. I became the manager. We decided to call the group Bagida’waad Alliance, which means “they set a net” in Anishinaabemowin. This came together rather quickly, but in a good way. We incorporated with the mandate to promote research and education about the impacts of climate change on the waters and environment of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, encourage our youth to document the stories of the Elders, and promote more active stewardship of the lands and waters.

Bagida’waad Alliance became an important part of my life. It has helped me deal with the transition from being part of a fishing family running our own business to someone who shares the story of climate change and its impact on lake whitefish. Bagida’waad deals with a number of really heavy topics like keeping shorelines natural, invasive species, loss of habitat, food sustainability, and of course, climate change and the decline of the lake whitefish. We do a whole range of initiatives: shoreline cleanups throughout the traditional territory of Saugeen Ojibway Nation, online environmental webinars and Anishinaabemowin language classes, an online store, net seaming workshops, hosting college students for a week, pottery workshops, a creek revitalization project, planting food sources, and a pretty cool community meal-sharing event in October 2018. A major focus of our work has been in the area of youth engagement, education, and stewardship. We use innovative technology and digital media to reach younger audiences and have interactive engagement, such as sharing drone footage, using augmented reality for education at the creek, and doing live virtual eco hikes for Elders.

I see Bagida’waad as applying a strength-based approach to all of our projects (Brough et al. 2004). Anishinaabe people have always used humour in telling difficult stories. Humour is also a key tool of decolonization and central to Indigenous education and pedagogy (Leddy 2018). I find humour helps make complicated issues a bit more fun or engaging. I remember doing a shoreline cleanup wearing an inflatable dinosaur costume. There were so many youths who wanted to know what I was doing or bring me litter just so they could see the costume up close. The adults also wanted to chat more and were happy to help clean up a bit or take a business card.

It’s an important topic—talking about litter and keeping our waterways clean. But it is equally important to show people ways they can help and to add a bit of laughter into a shoreline cleanup. It makes those cleanups a bit more memorable and a chore to look forward to.

Our social media posts as Aquaman are another way we use humour to communicate information about climate change and the state of the environment. Research has shown the importance of communicating climate science through simple, clear messages and repeating those messages often to encourage uptake and connection with the information—lessons we have tried to take to heart in our outreach.

The fog had begun to lift. I felt a weight coming off my shoulders as I felt the solid ground beneath me.

Engaging youth in climate action and education

I know my strengths are in numbers and in timelines. Others on our support team have strengths in writing or reading legal documents or knowing plant names. I know I really enjoy finding out what people are passionate about doing and supporting whatever that might be. It is always amazing to see what a person’s passion is capable of producing.

In 2019, we started a project to engage Saugeen Ojibway Nation youth in documenting knowledge and stories from Elders in the fishing community about the changes they had observed. And in October 2019 we initiated a partnership with Dr. James Stinson, affiliated with York University’s Dahdaleh Institute of Global Health Research and Young Lives Research Lab in the Faculty of Education. The goal of the partnership has been to expand on our youth-centred approach to research and education.

In March 2020, we were jointly awarded a Partnership Engage Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) for a project that would engage youth in producing short documentary films about climate change and planetary health. This project recently concluded with an online film festival showcasing seven youth-made films. Six of these films have been uploaded to the Youth Climate Report, an online database of youth-produced films associated with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). To date, more than six hundred videos produced by young people (aged eighteen to thirty years) reside on the Youth Climate Report database, showcasing visible evidence of the research, effects, and solutions to climate change. The youth-produced films added to the database each year are screened annually at the UN Climate Change COP conferences, where the films serve as a resource for UN policy-makers. One of the films created last year by Christopher Akiwenzie, who is my oldest son, specifically addressed the issue of ice coverage on the Great Lakes and the impact on populations of lake whitefish. We will be continuing this collaborative and youth-centred work with Dr. Stinson over the next three years through a SSHRC Partnership Development Grant for our project, “Planetary Health Partnership: Anishinaabe Youth Guardians and the Practice of Living Well With the World.” The project extends and builds on our ongoing collaboration with York University and will explore Indigenous guardianship and land-based experiential learning as a model of cultural revitalization, environmental stewardship, and climate action.

Victoria and I met Gwen MacGregor, an instructor at the University of Toronto, through one of the webinars we were hosting in 2019. She seemed really friendly and open-minded. Gwen asked us to meet a few weeks later in person. We visited mostly online because of COVID and kept in touch by email. She was so passionate about the environment and climate action. She mentioned that she would like to introduce us to another friend of hers who also was a professor at the University. When we met Marla Hlady, we knew that these were people we wanted to work with. It surprised me that both professors made the effort to come and meet with us in person this past summer. I know the drive to the city of Toronto and it is a long one. It showed me their commitment to do things right. Then an idea was born to create a land-based course to be offered to the students. Victoria and I thought it was a pretty cool idea.

We built a strong and trusting relationship and shared a lot of stories. So when the discussion turned to working together by offering an experience to students, it just seemed to be the next logical step. The students, I felt, would benefit immensely from the course we decided to develop together. We designed the whole course together, in full collaboration, slowly and with many open discussions, to ensure it would benefit the students and be done with the community and environment in mind. We’ve had a great time with the students this spring and really enjoy our conversations when we zoom into their classroom. I always looked forward to reconnecting the students, Gwen, and Marla, to the natural environment and sharing the beauty that surrounds me here in Neyaashiinigmiing.

With Bagida’waad and its supporters, the fog is burning off and the path forward is easier to find.

See you on the shoreline

Our planet needs our help. Our biodiversity is slowly disappearing. We need to reconnect to the world around us. We need to ensure future generations have a chance of experiencing a stable climate. We need to support each other in the positive changes we are making to ensure we leave the planet better than we found it. Bagida’waad Alliance is working on a number of projects that focus on the environment and culture. We have done a creek rehabilitation to provide shade to life forms in the water and help manage erosion issues naturally. We are doing eco-hikes to share stories of the importance of the ecosystem and how we are interconnected with nature. We do water testing using citizen science to teach others the importance of documenting changes in their local waterways. And we host online discussions about a variety of topics like native or invasive plants or fish or insects. All of these projects involve sharing Anishinaabe stories and language in appropriate ways.

If you ever want to join us on the shoreline, we will have a costume waiting for you!

Policy and initiative recommendations

General policy recommendations

- Implement free, prior, and informed consent at all levels

- Develop and implement a Climate Change Adaptation and Education Plan

United Nations

- Develop programs to fund community engagement with Indigenous youth and land-based Guardians initiatives

- Develop an integrated, holistic ecosystem approach to species protection that is co-developed using Indigenous ecological knowledge

Federal policy recommendations

- Support Indigenous and youth-led climate change and planetary health education and awareness building

- Promote process of two-eyed seeing and ethical space in which Indigenous knowledge and Western science are treated as different but complementary knowledge systems to inform policy

- Support Indigenous Guardian programs in every Indigenous territory, including multi-year funding through contribution agreements

- Develop further Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and Indigenous Community Land Trusts

- Indigenize Canadian climate policy so that climate action and Indigenous sovereignty are operationalized in a mutually supportive relationship

- Support locally developed and Indigenous-led solutions for adapting Indigenous fisheries toward sustainable economic and sustenance solutions, either continuing fishing or moving into other roles such as sharing knowledge

- Implementing free, prior, and informed consent in all Ministries

- Promote Indigenous-managed areas for conservation.

- Do a comprehensive review of policies to produce a report that can limit the movement and propagation of invasive species through a variety of existing means, including seed companies, nurseries, commercial boats, transportation, etc.

- Legislate an Indigenous-led and managed Crown Corporation for Indigenous Initiatives with stand alone multi-year operational funding, including additional funds for their programs to disperse

- Implement the Inclusion, Diversity, Equity & Accessibility (IDEA) Good Practices for Researchers

Provincial policy recommendations

- Implement co-development and co-management of all resources

- Encourage the use of disturbed areas for new development

- Implement more protected natural spaces

- Develop and support Indigenous land-based learning courses and modules throughout the educational curriculum

- Support local food networks, including commercial kitchens for local food processing

Regional government recommendations

- Develop an invasive species plan to limit their spread and propagation

- Develop a tree fence and hedgerow policy to support farmers in keeping and/or adding trees along roadways, between fields, and near waterways

- Regulate and encourage waterfront properties to keep their shorelines natural

- Introduce fees for development applications to pay for Indigenous people’s services to review the applications

- Implement eco-passages for wildlife

Indigenous government recommendations

- Implement eco-passages for wildlife

- Create a Guardians program

- Partner with local grassroots organizations on ecological restoration projects

Local government recommendations—municipalities

- Introduce bylaws that allow for and promote the planting of edible plants, including trees, bushes, herbs, and vegetables, in parks and public spaces

- Plant non-invasive species in parks and public spaces, including plants that are useful to people

- Support local farmers’ markets to have consistent space, advertising, and staff support

- Implement eco-passages for wildlife

Local government recommendations—Band Councils

- Implement eco-passages for wildlife

Foundations, charities, not-for-profit organizations

- Ensure boards have at least two representatives from Indigenous rights holders

- Organize an Indigenous Advisory Board

Businesses

- Discuss upcoming business opportunities with local Indigenous businesses to see if partnerships are possible

Educational institutions

- Support land-based learning courses and modules throughout the educational system

References

Brough, Mark, Chelsea Bond, and Julian Hunt. 2004. “Strong in the City: Towards a strength-based approach in Indigenous health promotion.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 15:3. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE04215

Leddy, Shannon. 2018. “In a Good Way: Reflecting on Humour in Indigenous Education.” Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 16(2), 10–20. https://jcacs.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jcacs/article/view/40348 Whitinui, Paul. 2013. “Indigenous Autoethnography: Exploring, Engaging, and Experiencing ‘Self’ as a Native Method of Inquiry.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43:4. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0891241613508148