Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series of Indigenous-led climate research, produced in co-operation with the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources.

By Jean L’Hommecourt,1 Marie Boucher,1 Gabe Desjarlais,1 Joe Grandjambe,1 Martha Grandjambe,1 Dora L’Hommecourt,1 James Ladouceur,1 Clara Mercer,1 Douglas Mercer,1 Edith Orr,1 Audrey Redcrow,1 and James “Scotty” Stewart1

with Alexandra Davies Post,2 Christine A Daly,3 Bori Arrobo,1 Gillian Donald,4 Dan McCarthy,3 David A Lertzman,3 and S Craig Gerlach3

Affiliations: Fort McKay First Nation,1 University of Waterloo,2 University of Calgary,3 and Donald Functional & Applied Ecology Inc.4

Overview

This is a chapter in a story that is still unfolding. It is a story about a First Nation and academic co-researchers who learned from one another and, in doing so, co-created intercultural planning tools to prioritize Indigenous voices and leadership in Canada’s energy transition.

A gap exists in Canada’s oil sands mine closure and reclamation policies and practices that results in the exclusion of Indigenous treaty and Indigenous rights holders from meaningfully stewarding the repair of their degraded traditional territories. While government policy and regulations require that the impacts of mine projects on Indigenous rights holders and the land be mitigated, current approaches to mine closure and reclamation have fallen short, especially regarding mine closure’s social and cultural aspects. It is important that both people and natural elements be included in the plans for repair of degraded landscapes in order to sustain landscapes as well as the societies and cultures that depend on them. To adequately prepare for the energy transition, the oil and gas sector—Canada’s largest emitter and contributor to climate change (Government of Canada 2021)—must reckon with the historic and ongoing impacts on the land and on the Indigenous rights holders who continue to feel the effects of this industry’s footprint. This is of particular concern to the Fort McKay First Nation, whose traditional territory within Treaty 8 contains the Athabasca oil sands and which has been degraded by oil sands industrial activities.

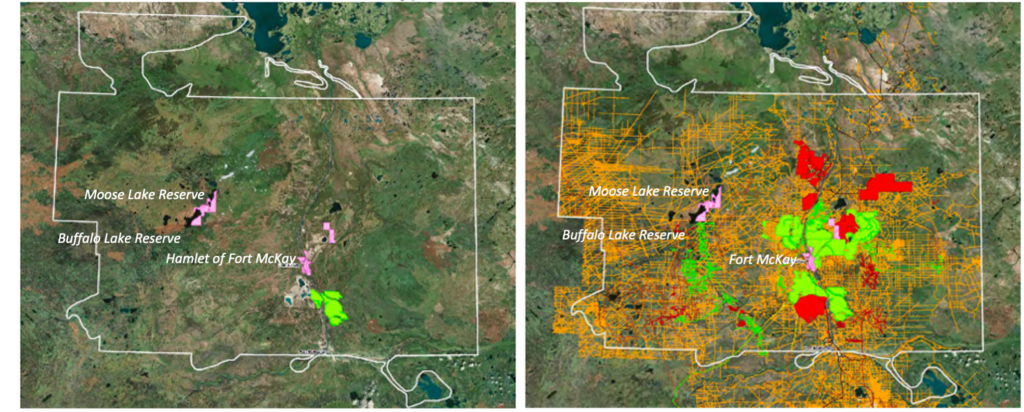

For decades, Fort McKay community members have raised concerns about the cumulative impacts of the oil sands industry on their traditional territory. Figure 1 shows a bird’s-eye view of the industrial disturbance within the Fort McKay Traditional Territory (outlined in white), both in 1967 (left) when the first oil sand activity began commercial-scale operations and today (right). The pink areas represent Fort McKay First Nation reserve lands, the green are active oil sands projects, the red are approved but not yet operating projects, and the orange are primarily oil and gas exploration areas.

In 1967, when operations began, community members in Fort McKay First Nation had no recourse for consultation and engagement with oil sand operators. Decisions about mine closure and reclamation planning were made without input or consideration of the Cree and Dënesuliné (hereafter Dene) people who have lived on that land since time immemorial. By the 1980s, Fort McKay First Nation community members were being told that the land would be returned to what it was pre-disturbance, and the effects of the operations would be minimal. Today, companies acknowledge the landscapes will be markedly different than the original conditions, yet returned to the regulatory target of a self-sustaining boreal forest ecosystem.

There’s 55 years of that project on Fort McKay First Nation Traditional Territory but not 55 years of involving Fort McKay First Nation in decision-making or planning.

Bori Arrobo, Director of Sustainability at Fort McKay First Nation

The effects of these early mines include not only the cumulative effects on the land but decades of planning and decision-making that set a precedent in the region with newer projects and operators. These maps don’t just tell us about the past but also what is to come in Fort McKay First Nation Traditional Territory. Figure 1 (right) shows the approved but not yet operating projects (in red) that will extend the more-than-50-year legacy of the oil sands industry well into the future. There is a legal requirement for Indigenous engagement and consultation on oil sands projects (Government of Alberta, 2013), but inclusion of Indigenous voices and needs in mine closure and reclamation planning decisions specifically remains a gap in government and oil sands industry policy and practice.

In 2018, Fort McKay First Nation partnered with the universities of Calgary and Waterloo to continue the journey to have their unique Cree and Dene perspectives and knowledges represented in the repair or reclamation of their lands and waters. Together, we created the Co-Reclamation Research Project in service of a movement towards a participatory and inclusive planning approach that empowers Fort McKay First Nation with an equitable role in mine closure and reclamation decision-making. The project co-created reclamation and closure planning tools and processes to support communication of Fort McKay’s socioeconomic, environmental, and cultural priorities and perspectives during repair of oil sands-degraded landscapes. An oil sands company participated in early aspects of the project.

In the next chapter of this story, we describe the research activities and some key lessons the co-researchers learned from one another through the Co-Reclamation Project.

These lessons contain truths, tools, and pathways that may prove useful to Fort McKay First Nation, other Indigenous Nations that adopt them, the energy industry, and the federal, provincial, and territorial governments in Canada navigating the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Including:

- A description of what the traditional lands and waters, and their intimate relationship to culture, mean to Fort McKay First Nation community members;

- The Two-Roads Approach—an intercultural governance model for inclusive energy project partnerships that supports multiple cultural paradigms in project decisions;

- The Cycle of Respect—an indigenized code of conduct developed for effective intercultural communication and collaborative action; and

An Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework—inspired by the Two-Roads Approach and knowledge holders from Fort McKay, this framework details how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people can work together to reclaim lands degraded by energy projects using parallel paths that support distinct ways of knowing and being, while enabling inclusive decision-making at key planning bridges.

Land from the perspective of Fort McKay First Nation

Fort McKay First Nation has nearly 900 Cree and Dene band and community members. About 500 of them reside in the Hamlet of Fort McKay, which is located on the shores of the Athabasca River in what is now known as Northeast Alberta. Both historically and today, Cree and Dene community members depend on their ability to hunt, gather, fish, nurture, and work in nature within their traditional territory to sustain their cultural heritage, languages, access to land, and practice of rights.

However, the extensive oil sands industrial activities impact their traditional land use activities and, hence, the sustainability of their culture and way of life. For decades, Fort McKay community members have talked about the impacts the industry has on the land. During our gatherings, Fort McKay co-researchers often describe the pristine beauty of the land before the effects of the industry were felt. Elders Edith Orr and Marie Boucher spoke of a time when birds were heard more frequently in the spring, berries were easier to harvest and tasted better, and the air smelled fresher and cleaner than today.

It is important to remember what the land was like before widespread oil sands industrial disturbance, says Bori Arrobo, Director of Sustainability at Fort McKay First Nation. “Before we can start talking about reclaiming the land, we need to recognize the land before disturbance happened. We need to recognize who were the original people on the land. How the original people live on the land. And we need to recognize and acknowledge the impacts, the losses from a degradation of that land.”

Jean L’Hommecourt is Dene and a Fort McKay First Nation community member on Treaty 8 territory. She is a descendant of Treaty 8 signatory Chief Adam Boucher. Jean is currently employed with the Fort McKay First Nation Sustainability Department as a Traditional Land Use Specialist, serves as a board member of the Keepers of the Water Group, and is the community liaison on the Co-Reclamation Project. In 1967, when the first oil sands company began operations, Jean was just four years old (see the left image in Figure 1). She reflects on how she remembers her childhood in the boreal forest of the Fort McKay Traditional Territory, and the effects the oil sands industry has on her and her community:

“My dad used to take us out on the land on the river and across to the Birch Mountain area where I used to walk with him. And now looking at the other side, the other picture, it’s like, you can’t even make sense of where you are or where things are. The land was once pristine. So, it kind of makes you, makes me feel lost looking at the second map [referring to the right map in Figure 1]. It affects me emotionally because just looking at it makes me realize how much was taken from me. [The land] keeps our values as First Nations. But slowly we are seeing everything being taken from us. We need you to fix all the stuff industry did. We’re missing a big piece here.”

Next, we highlight Fort McKay’s work in developing an intercultural governance model for inclusion of their deep knowledge and voices in reclamation of their homelands, and discuss how we applied this model in our Co-Reclamation Project.

Applying a Two-Roads Approach to co-reclamation and the energy transition

Energy resource projects perpetuate environmental and climate injustices when they focus solely on the priorities, perspectives, and processes of companies and federal, provincial, and territorial governments to the exclusion of the traditional territory Indigenous rights holders’ voices and approaches.

The Two-Roads Approach was developed from 2009 to 2013 by Fort McKay community members, other members of Indigenous nations, oil sands operators, and the Alberta government through the Cumulative Environmental Management Association (CEMA) Biodiversity Traditional Knowledge Study (Two Roads Research Team 2011, 2012). CEMA generated recommendations to implement a Two-Roads Approach to include Indigenous community members and incorporate their Indigenous Knowledge into reclamation and closure planning. The team applied a Two-Roads Approach to the Co-Reclamation Project in order to create an ethical space (Ermine, 2008) for multiple cultures to share the best of both worlds (Lertzman, 2010) while reclaiming the degraded Fort McKay Traditional Territory. The Co-Reclamation Project was the first attempt to apply this intercultural reclamation and closure planning approach.

We are all treaty people

While a Two-Roads Approach was created over a decade ago through the multistakeholder group CEMA, it was similarly used by our ancestors to understand each other and make treaty agreements to share the land and its natural resources. This intercultural government model co-created by Fort McKay First Nation and members of the oil sands industry can be used today to support inclusive renewable and non-renewable energy project partnerships that support multiple cultural paradigms in project decisions—from exploration through to operations, project reclamation, and closure.

L’Hommecourt shares her experiences as a Two-Roads research team member who helped create the Two-Roads Approach and, later, applied it as a co-researcher of the Co-Reclamation Project:

“We were sitting together as a group in CEMA that included representatives from five First Nations in the region. The Two-Roads Approach is something we came up with while talking about how to bring forward our concerns and issues and how to deal with them in a manner that was respectful of our Indigenous views and inputs. We have a different set of values than the mainstream or settler society as far as land connections and a connection to Mother Earth. We walk different paths. A lot of times we get pushed into a separate way of thinking that’s not ours. In order to keep our values, we want to walk a separate road. We walk together and bring our values and ideas together at certain points along our separate routes. We try to coordinate those points by building bridges and coming to some kind of understanding while working alongside each other. A Two-Roads Approach goes all the way back to the Treaty signing. Our ancestors had to communicate in a way that was understood by the newcomers and come to an agreement ‘for as long as the rivers flow, grass grows, and sun shines.’ Those terms are a perfect example of universal understanding by everybody on Mother Earth that our identity as Indigenous Peoples is as peoples of the land.”

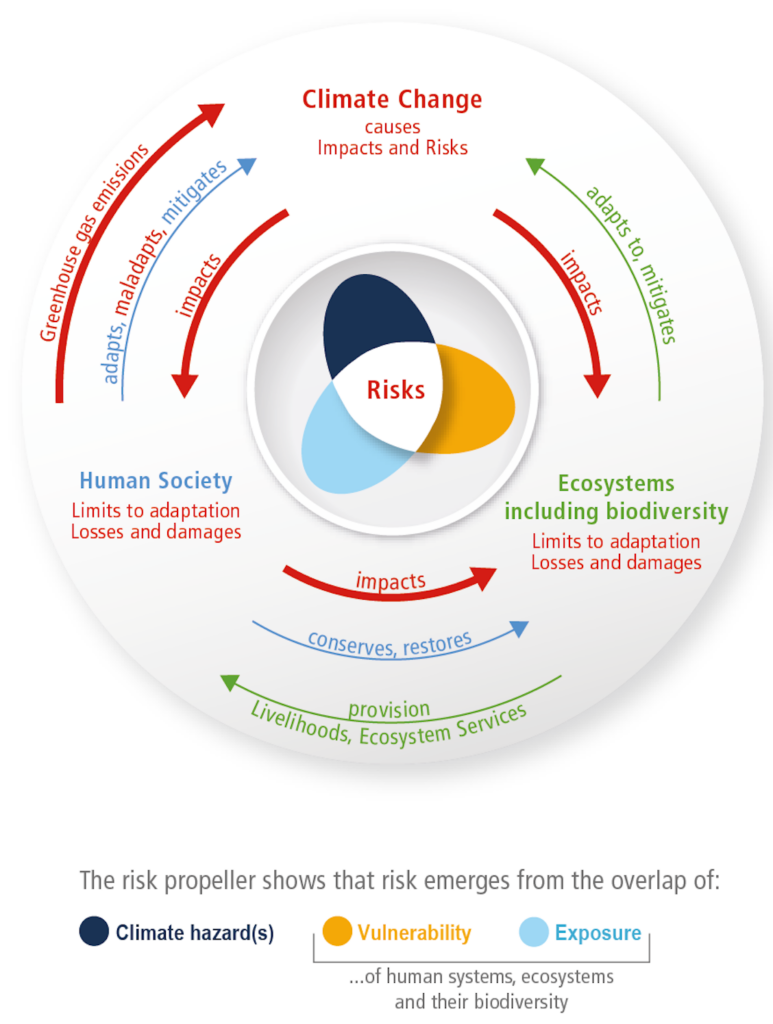

Climate change impacts, as well as the methods to mitigate them and build resilience, can be understood from both a scientific road and an Indigenous road (Figure 3). Here we present both western and Fort McKay ways of knowing and understanding climate change in a two-row visual code as described by Goodchild (2021):

A scientific perspective, according to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2021, 2022), holds that an atmospheric increase in greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane since 1750 is unequivocally caused by the burning of fossil fuels. Increased greenhouse gas levels have resulted in global surface temperatures warming by 1.09oC in the last decade relative to 1850-1900, with 2.7oC of warming expected this century unless significant further commitments are made to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades (Climate Action Tracker 2021).

Climate change is already resulting in more dangerous and extreme weather, creating widespread suffering in every region on Earth, and the effects will only intensify with each additional warming increment (IPCC 2021, 2022).

From a Fort McKay member perspective as described by L’Hommecourt:

“It is our belief that everything on Mother Earth was given to us for a reason. Everything has a purpose. Everything has a spirit. So, with regards to climate change, the trees are the most important.

The trees are all there to give us life and to be protective of us. They stand strong and take in all the toxins. They cleanse the air for us and give us life’s breath. As Indigenous Peoples, we recognize all the many uses and different kinds or species of trees. We want to continue to protect those trees, so our future generations have those to depend on too.

The soils, the muskeg [also known as peatlands] are especially important because they act as a filter. Muskeg is a big sponge that soaks up all the toxins and the carbons. Muskeg protects us from climate change. But the land and that map has all been ripped out, dried up and stored away. Even though it was stored away in stockpiles for many years, there’s no way they can bring back muskeg that serves the purpose it was first put on Earth by the Creator.

All the land transformations have changed our climate, the directions of the winds, the velocity of the winds, the water systems, and species are disappearing. Now we’re beginning to suffer the consequences. Our ancestors warned us that we were going to come to a time where we’re going to see hardship like we have never seen before. And it’s all due to the planet’s biggest predator, mankind, destroying Mother Earth.”

Adoption of the Two-Roads Approach enables multiple worldviews, knowledges, and governance systems to exist together in balance. This approach was chosen for its ability to create spaces or bridges for Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants to sit in between and learn from different cultural paradigms and knowledge systems (Goodchild 2021). Moore (2017) describes this space as Trickster consciousness, an in-between place that disrupts the opposites and liberates people from conventional thinking. These bridges may be the optimal areas from which to examine complex challenges, like climate change, and to create an ethical energy transition roadmap for Canada that privileges multiple voices and knowledges, including Indigenous Nations like Fort McKay.

The Cycle of Respect: Towards an intercultural governance model

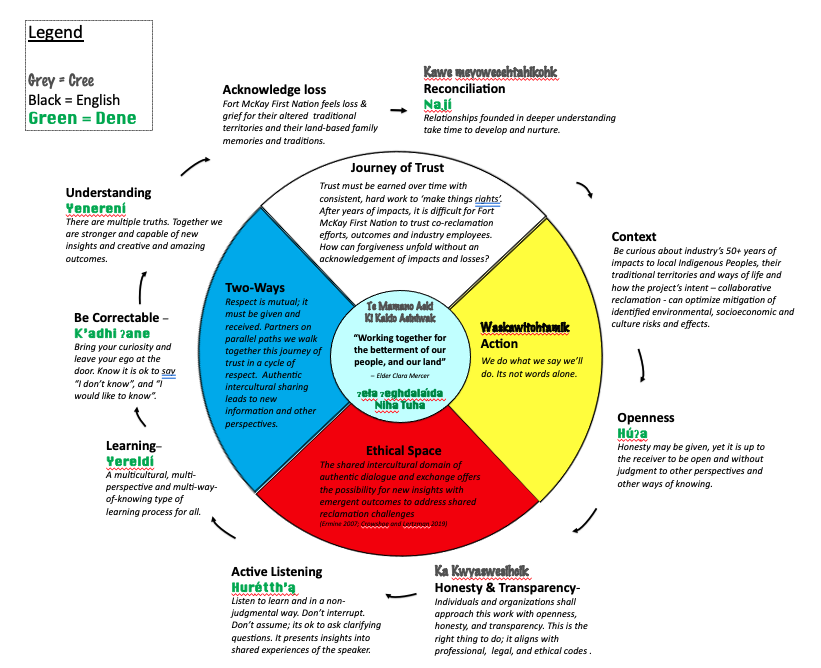

Before the co-researchers could begin to co-reclaim the land that supported Fort McKay’s collective voice and vision, we recognized a need for new rules of engagement that would not reinforce harmful patterns. First, co-researchers spent time on the land together to understand Fort McKay expectations for the environmental quality needed to support their traditional land uses, explore an oil sands company’s scientific knowledge and approach to reclamation, and support relationship (re)building in a grounding setting. Later, the Cycle of Respect was co-created to guide the ethical behaviour and actions of co-researchers when their different roads came together to plan for mine closure and reclamation. This new tool was designed to support a shared ethical space where both Indigenous and non-Indigenous co-researchers could meaningfully and ethically engage with one another (Ermine, 2008).

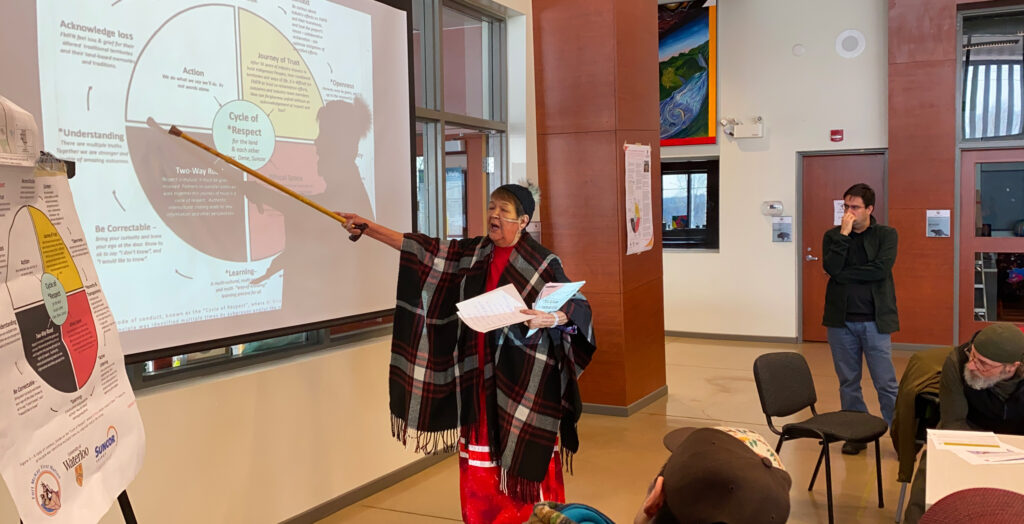

The Cycle of Respect is an intercultural tool that contains a set of principles to assist oil sands operators and government agencies with ethical intercultural dialogue and meaningful engagement with Fort McKay First Nation. It was developed using traditional Indigenous decision-making processes for dialogue and knowledge exchange: talking circles and storytelling. Other Nations and industries may choose to adopt, modify, and apply the Cycle of Respect to their respective contexts.

The Cycle of Respect was co-created by Fort McKay, an oil sands company, and academic co-researchers at the Youth Centre in the Hamlet of Fort McKay. Sitting in a talking circle, each co-researcher shared a story from past government, industry, and Indigenous engagements that contained a teachable moment. One by one, each co-researcher passed an eagle feather around the circle and shared their memorable experiences, good and bad. Once the circle was closed, co-researchers came together in two smaller circles to identify key principles that could support a respectful, safe, and collaborative intercultural space for reclamation dialogue and action. Through intercultural discourse, theme identification, and validation over the course of several meetings, the teachable moments transformed from a simple list of experiences to a dynamic and interrelated set of guiding principles. These principles were transposed onto a medicine wheel using Cree, Dene, and English languages and named the “Cycle of Respect” by Elder Scotty Stewart (Figure 3).

Within its centre, the Cycle of Respect contains the motto for the Co-Reclamation Project, which was coined by Elder Clara Mercer. In Cree the project motto is Te Mamano Aski Ki Kaklo Asiniwak and in Dene it is ɂeła ɂeghdalaı́da NihaTuha, which both roughly translate as “working together for the betterment of our people and our land.”

Following guidance from Fort McKay Elders, principles derived from the stories were woven together within a medicine wheel containing Cree, Dene, and English languages; Cree colours; and quadrants representative of the four seasons and four directions. Adoption of the principles starts with foundational elements in spring (yellow, east) followed by continued growth through the addition of more principles during summer (red, south), fall (blue, west), and winter (white, north). Each principle feeds into another: for example, several Fort McKay co-researchers stressed that to participate in a good way, one must be honest and transparent with one another in order to be open to receiving new understandings. Each principle is relationally bound to the next and all must be embodied for a chance to participate meaningfully in intercultural collaboration. The work to communicate the Cycle of Respect principles in Cree, Dene, and English languages remains an ongoing but integral piece of this story. As the dearly missed Elder Clara Mercer said, “our [Cree and Dene] languages are very, very important. It is our identity. It is who we are and what we are. And our whole connection to Mother Earth.” The Cycle of Respect and the methods used to create it offer a pathway for Indigenous Nations to take when (re)building relationships and engaging with settler institutions, including government, industry, and academia. As Canada transitions to a low-carbon economy, tools like the Cycle of Respect are key to ensuring that there is a foundation of respectful communication that enables energy planners, policy makers, industry and government representatives, and other decision-makers to understand Indigenous people’s vision for the future of traditional Indigenous territory.

Cultural Reclamation and Climate Mitigation: The Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework

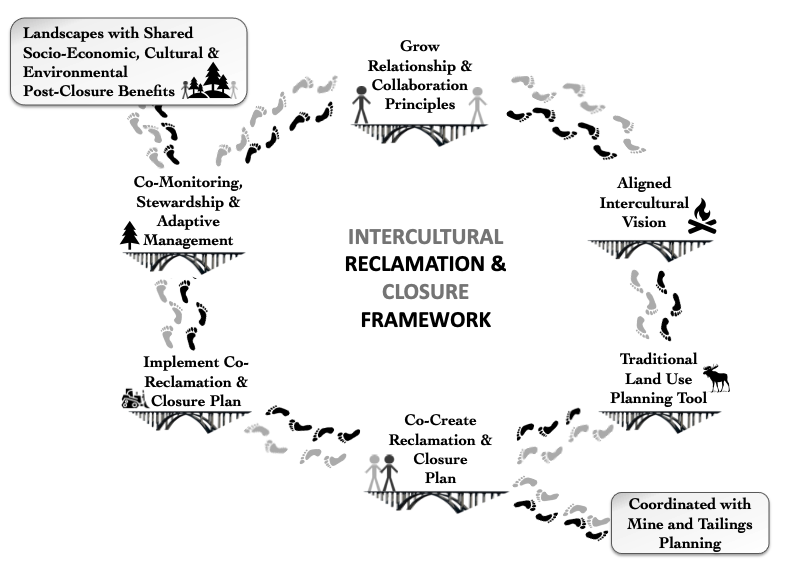

In this chapter of the story, we describe a new process that was created by co-researchers for the oil sands industry, government, and Fort McKay First Nation to use when planning for the future of Fort McKay’s traditional homelands after closure of an oil sands project. It is called the Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework. Lands reclaimed using this new process are proposed to have shared socio-economic, cultural, and environmental post-closure benefits (Figure 4).

The illustration of the framework was inspired by the Two-Roads Approach (Two Roads Research Team 2011, 2012) and lessons shared by the late Elder Clara Mercer, L’Hommecourt and the late Dr. David Lertzman. The framework depicts an oil sands company and Fort McKay walking parallel paths and meaningfully working together on reclamation and closure at key bridges to connect past, present, and future generations with the repaired landscape. Elder Clara Mercer shared that the “first seven strands of sweetgrass represent the seven generation behind us … [those who] made the trails [Fort McKay First Nation] have been walking up until now … the old trails have been destroyed … by dams, industries. So now our ancestors are having a hard time to find us to help us heal.” Dr. David Lertzman shared his reflections about breaking trail in deep snow: “breaking trail under these conditions is pretty tough going. It’s harder. Takes longer. And going up hills is more like swift hopping, really … so it’s a tough journey, but it’s a good journey because I know that the harder it is for me to break trail the more someone else after me is going to appreciate it.” The Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework illuminates six key bridges or phases for distinct cultures walking their own paths to meet at to share knowledges and co-create reclamation and closure plans that enable future generations of Fort McKay to stay connected to their ancestors through reclaimed ancestral trails. The Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework is meant to be used in combination with the Cycle of Respect, whereby the Cycle of Respect principles guide participants’ actions when they meet together at each of these Framework’s recommended bridges.

The re-establishment of vegetation, forests, peatlands, and traditional land uses on land disturbed by energy projects are important cultural and life-sustaining climate mitigation actions to Fort McKay. The six bridges of the Intercultural Reclamation and Closure Framework that support these actions are:

- Growth of relationships and establishment of reclamation collaboration principles: This foundation should precede energy project approval and continue throughout project operations and closure (e.g., by using an intercultural code of conduct to support dialogue and mutual learning).

- An Aligned Intercultural Closure Vision: A shared idea about the future reclaimed landscape that acts as a guiding light for mine closure and reclamation planning and design decisions.

- Design of a Traditional Land Use Planning Tool: A Fort McKay-created geospatial planning tool communicates where and how to incorporate key traditional land use features into reclamation and closure plans from their unique worldview.

- The Making of a Co–Reclamation and Closure Plan: This plan is made with (not for) Fort McKay First Nation with support from the shared Intercultural Closure Vision, Traditional Land Use Planning Tool, and the best of reclamation science.

- Implementation of a Co-Reclamation and Closure Plan: The degraded landscape is co-reclaimed (i.e., land recontoured and the re-establishment of soils, plants, wildlife habitat, and Fort McKay access) using the Co-Reclamation and Closure Plan.

- Co-Monitoring and maintenance: Monitoring data is gathered from reclaimed parcels of land using a Two-Roads Approach to determine whether a reclaimed landform has achieved the aligned closure vision or not. Maintenance and/or adaptive management is applied when the landform is not meeting the target (Davies Post forthcoming).

The framework is a work in progress at this point in our story, as it continues to be refined and validated by Co-Reclamation co-researchers (Daly et al. forthcoming).

Here we will explore an example of how the second bridge, an aligned intercultural closure vision, was co-created between Fort McKay and an oil sands company. For context, it is considered a good practice for mining companies to engage affected stakeholders and Indigenous Peoples to enable a shared vision and shared responsibilities in mine reclamation, closure planning, and post-mining results (ICMM 2019; LDI 2021; MAC 2008; MAC 2021; Morgenstern 2012). After all, Fort McKay First Nation will live with the socioeconomic, environmental, and cultural results of mine reclamation and closure decisions for generations. So, it was significant when Fort McKay and an oil sands company made gestures towards a shared idea about the future reclaimed landscape (Table 1). This milestone—creating parallel visions—occurred using Fort McKay protocols and practices in the community of Fort McKay during February 2020. For complete details, see Daly et al. 2022. Briefly, Fort McKay shared big picture aspirations and values that described successful implementation of mine reclamation and closure of their traditional territory from their individual perspectives. This included describing what they want to see, hear, and experience on reclaimed lands in the future. The sharing of ideas within a talking circle supported a collective understanding of individual ideas, a refinement of ideas into themes, and ultimately a realization of the Fort McKay vision. Later that month, the Fort McKay closure vision and an oil sands company’s vision of success were communicated within a talking circle composed of Fort McKay band members, oil sands company representatives, and university co-researchers. This collective talking circle resulted in the shared decision to work together using parallel visions. This decision demonstrated shared research project control and authority and alignment between the visions in the following ways: working together on reclamation; reciprocal learning; and improving relationships. Fort McKay’s vision emphasizes that inclusive reclamation practices, such as using a Two-Roads Approach and creating a mutually beneficial closure reclamation practices, are acts of reconciliation.

| Oil sand company vision | Fort McKay First Nation Vision |

|---|---|

| Collaboratively reclaim impacted land with Fort McKay First Nation to enhance reciprocal learning in land stewardship, relationships, and trust in reclamation and closure outcomes. | Reclaiming the land is a form of reconciliation, and Fort McKay First Nation must define those targets. Part of reconciliation is to recognize the land in its original state, who are the original peoples of the land, the impacts which have been done, and to acknowledge loss. We will achieve this through long-term commitment with proper ceremony, First Nation (Cree and Dene) languages and knowledge, and the best of reclamation science to foster mutual respect, understanding, and respect, and bring back respect to the land. |

Table 1: Project and/or mine closure visions described from parallel roads (Daly et al. 2022) using a two-row visual code format from Goodchild (2021).

A second research method or activity was used to explore Fort McKay and company closure visions. During November 2019, a Fort McKay co-researcher designed and led a reflective activity on land stewardship perspectives in the context of mine reclamation and closure. First Nation, company, and university co-researchers were asked to paint an individual or small group mine closure vision on modern versions of Fort McKay traditional shields (Figure 5). Later, they held their art up for fellow co-researchers to view while telling the story of the meaning behind the artistic interpretation of a mine reclamation and closure vision. For instance, the vision that Gillian Donald, long-time technical advisor to Fort McKay First Nation, has for mine closure and reclamation of the Fort McKay Traditional Territory is as follows (Figure 5): “Water is a critical element of the environment, and so I tried to paint in the bluey-green area of this idea that reclamation will ultimately create a landscape that has water flowing through it and supports ecological processes…. When we drive to [Fort McKay] … the landforms being constructed at the mines … stay there for a really, really long time. Why do things take so long to be reclaimed? When you drive by [east mine] for years and years and years, there’s a big sandy area with a huge sign that says “Reclamation in Progress.” So, you think, “what reclamation is happening there?” I understand the process because I read the closure plans and I know it takes a really long time. But if nobody is reading those plans, they’re driving by there all the time, [thinking] why does it take so long? So, that’s kind of what this stretch of brown is there for—that the landforms are there and take a really long time to build at the mines. Then, once there’s little parcels that are ready for reclamation, as time progresses. But it takes a really long time and eventually this would transition into an integrated landscape that has water and vegetation.”

The potential for oil sands companies and Indigenous Nations like Fort McKay to align on intercultural closure visions was demonstrated across individual, and within small-group, traditional shields. There were similar reclamation planning elements across the closure visions, such as water, trees, and return of wildlife. Also, some company and Fort McKay co-researchers elected to create small group traditional shields together, instead of personal art pieces. These small group visions were communicated using plural pronouns and displayed personal accountability. For example, co-researchers made statements such as, “that’s our idea for reclamation” and group members signed their collective artwork. A company co-researcher said, “I could hear everyone talk about trees. We heard water and trees the most. We wanted to include that, so the three of us put the tree in the center and then around the tree we each put things that reclamation meant to us.” After closure visions were shared through traditional shield art and oral stories within a talking circle, Elder Joe Grandejambe said co-researchers had “come together to make one story and everyone had almost the same idea, a good idea about the reclamation.” While Fort McKay co-researchers shared a unified voice that historic and contemporary mine reclamation and closure planning in their traditional territory does not currently meet the community’s land use needs, the Co-Reclamation Project’s intercultural planning activities and meaningful inclusion of Fort McKay provided hope for improved reclamation outcomes for future generations. Elder Edith Orr shared that she had “lots of hope for reclamation, for my kids to be able to enjoy the land one day, or their grandkids, or just our future generations.

In closing

The intercultural governance model, framework, and tools in this case study present innovative approaches to support the braiding of Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing and collaborative action. When applied, they support inclusion of Fort McKay’s voice and leadership in Alberta’s and Canada’s energy transition and the conservation and reclamation of the First Nation’s culture, which is permanently and intimately connected to its homelands. As we said at the beginning, this story is about Fort McKay First Nation and university co-researchers who learned from one another. The story is still unfolding. Time will tell if these intercultural research products are adopted into routine practice and policy by governments and the energy industry.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of the co-researchers who were lost along this research journey: Elders Clara Mercer and Doug Mercer; and mentor and friend Dr. David Lertzman. Funding was provided by the Alberta Conservation Association, an oil sands company, MITACS Accelerate, and University of Calgary scholarships. Research operated with university ethics approval and in accordance with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS).

References

Climate Action Tracker. 2021. Temperatures – Addressing global warming. https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/#:~:text=Current%20policies%20presently%20in%20place,warming%20above%20pre%2Dindustrial%20levels

Cresswell, Tome. 2004. Place: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cuerrier, Alain, Nancy J. Turner, Thiago C. Gomes, Ann Garibaldi, and Ashleigh Downing. 2015. “Cultural Keystone Places: Conservation and Restoration in Cultural Landscapes.” Journal of Ethnobiology 35 (3): 427–448. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-35.3.427.

Daly Christine A., Jean L’Hommecourt, Bori Arrobo, Alexandra Davies Post, Dan McCarthy, Gillian Donald, S. Craig Gerlach. 2022. Gesturing towards co-visioning: A new approach for intercultural mine reclamation and closure planning. Special Issue of The International Journal of Architectonic, Spatial, and Environmental Design.

Daly Christine A. (Forthcoming). Renewing ancestral trails: An intercultural mine reclamation and closure framework. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). PhD in Environmental Design, University of Calgary.

Davies Post, Alexandra. (Forthcoming). Indigenous-led monitoring, trends, and wise practices in Canada (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Waterloo.

Ermine, Willie. 2007. “The Ethical Space of Engagement.” Indigenous Law Journal 6 (1): 193–203. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/article/view/27669/20400.

Goodchild, Melanie. 2021. Relational Systems Thinking: That’s How Change is Going to Come, From Our Earth Mother. Journal of Awareness-Based Systems Change, 1(1), 75–103. https://doi.org/10.47061/jabsc.v1i1.577

Government of Alberta . 2021. The Government of Alberta’s Policy on Consultation with First Nations on Land and Natural Resource Management, 2013. https://open.alberta.ca/publications/6713979

Government of Canada. 2021. Greenhouse gas sources and sinks: executive summary 2021.

ICMM (International Council on Mining and Metals). 2019. Integrated Mine Closure: Good Practice Guide, 2nd ed. London: ICMM.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science

Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Valérie Masson-Delmotte, Panmao Zhai, Anna Pirani, Sarah L. Connors, Clotilde Péan, Sophie Berger, Nada Caud, Yang Chen, Leah Goldfarb, Melissa I. Gomis, Mengtian Huang, K. Leitzell, Elisabeth Lonnoy, J.B. Robin Matthews, Tom Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, Rong Yu, Baiquan Zhou Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

IPCC. 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Hans-O. Pörtner, Debra C. Roberts, M. Tignor, Elvira S. Poloczanska, Katja Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, Stefannie Löschke, Vincent Möller, Adrew Okem, B. Rama]. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

LDI (Landform Design Institute). “The 12 Principles of Landform Design.” Landform Design Institute, Accessed March 1, 2021. https://landformdesign.com/principles.html.

Lertzman, David Adam. 2010. “Best of Two Worlds: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Western Science in Ecosystem-Based Management.” BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 10 (3): 104–126.

MAC (Mining Association of Canada). 2008. Towards Sustainable Mine Closure Framework. Ottawa: MAC, 2008. https://mining.ca/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2021/08/TSM_Mine_Closure_Framework.pdf.

McCarthy, Daniel, Martin Millen, Mary Boyden, Erin Alexiuk, Graham S. Whitelaw, Leela Viswanathan, Dorothy Larkman, Giidaakunadaad (Nancy) Rowe, and Frances R. Westley. 2014. “A First Nations-led Social Innovation: A Moose, a Gold Mining Company, and a Policy Window.” Ecology and Society 19 (4): 2–20. http://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06771-190402.

Moore Sylvia. 2017. Trickster chases the tale of education. Montreal (QC): McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Morgenstern, Norbert. “Oil Sands Mine Closure – The End Game: an Update.” Paper presented at the Third International Oil Sands Tailings Conference, Edmonton, December 3–5, 2012. University of Alberta Geotechnical Center and Oil Sands Tailing Research, Calgary.

O’Faircheallaigh, Ciaran, and Rebecca Lawrence. 2019. “Mine Closure and the Aboriginal Estate.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2019 (1): 65–81. https://www.mineclosure.net/elibrary/mine-closure-and-the-aboriginal-estate.

Svobodova, Kamila. 2019. “Life Post-Closure: Perception and use of Rehabilitated Mine Sites by Local Communities.” Paper presented at the 13th International Conference on Mine Closure, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, Perth, September 3–5, 2019. https://doi.org/10.36487/ACG_rep/1915_27_Svobodova.

The Biodiversity Traditional Knowledge Research Team. 2011. Renewing the Health of Our Forests: Biodiversity Traditional Knowledge of the Oil Sands Region. Compiled by: SENES Consultants Limited.

Two Roads Research Team. 2012. An Aboriginal Road to Reclamation: Values, goals and action for a homeland in the Oil Sands Region, CEMA Contract 2010-0022. Compiled by Deborah Simmons, SENES Fort McMurray: CEMA (Reclamation Working Group).