Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

Summary

Indigenous communities in Canada face disproportionate levels of risk from climate change—but not only from climate change. In Canada, there is very little research within the Indigenous context on the connections between the unnatural disasters of colonialism, land dispossession, and climate displacement. Through community-led research, we seek to document in this case study the long-term impacts of land dispossession, disaster displacement, and climate change in Siksika Nation, on Treaty 7 territory in southern Alberta, through interviews conducted with community members by Darlene Yellow Old Woman-Munro, a Siksika Elder.

Following the devastating 2013 flood event, Siksika evacuees experienced multiple phases of disaster displacement. Six long years after the disaster, some of the evacuees had not returned to their homes. Recovery has been an ongoing process with uncertain outcomes.

Through this case study, we challenge the widely used notion of a “natural disaster.” When examined from an Indigenous community perspective, and bearing in mind targeted long-term risk creation through colonial land dispossession combined with anthropogenic climate change, there is very little that is “natural” about flooding disasters in First Nation communities.

Our case study shows an example of self-determination in the community-led, culturally safe response to disasters of the Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre, a unique Siksika-led disaster recovery approach that addressed the physical, mental, cultural, and spiritual health needs of evacuees.

Introduction

The frequency and severity of disasters has been increasing over the past 30 years in Canada. In 2020 alone, insured damage for severe weather events across Canada reached $2.4 billion (IBC, 2021). Such floods, hurricanes and wildfires are often presented by the media, government, and response organizations as “natural disasters.” However, this notion of a “natural” disaster fails to tell the full story of the social determinants of risk and how disasters are exacerbated through inappropriate land use, fragmented governance systems, and activities prioritizing short-term gain and short-term electoral benefits (Lavell & Maskrey, 2013; Oliver-Smith et al., 2016). In particular, the “natural disaster” framing omits the ongoing unnatural disasters of denial, displacement, dispossession, and loss in Indigenous communities (Howitt, 2020; Howitt et al, 2012).

In this case study, we examine the unnatural impacts colonization continues to have on communities as they recover from disasters. Specifically, through community-led research, we document the long-term impacts of land dispossession, disaster displacement, and climate change in Siksika Nation based on interviews conducted with community members by Darlene Yellow Old Woman-Munro. Darlene is a Siksika Elder, a former community nurse, the former Chief, and the Former Director of the Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre. It is also based on Darlene’s reflections as a community leader.

Our research and writing team for this case study also included Emily Dicken, MSc, PhD, a woman of mixed Indigenous and European descent with over 15 years of experience working in the field of emergency management, and Lilia Yumagulova, MSc, PhD, a Bashkir woman with over 15 years of global experience in Indigenous community resilience. Our team met through the Advisory Circle for the Preparing Our Home program, an Indigenous youth-led program for community resilience.

Grounded in Indigenous methodologies, this community case study sought to create a culturally safe space to explore colonial land dispossession and disaster evacuations within the context of climate displacement. Climate change is projected to continue to drive increased risks over the coming decades, risks that will be compounded by non-climatic factors such as social, economic, cultural, political, and institutional inequities (IPCC, 2016). It is important to understand how disaster response and emergency planning measures can play a role in reducing harm and promoting healing instead of perpetuating vulnerabilities and inequities.

Disaster response and emergency planning measures can play a role in reducing harm and promoting healing instead of perpetuating vulnerabilities and inequities.

Our case study highlights the long journey home for Siksika evacuees who have been dealing with the long-term physical and mental health consequences of displacement, loss, and trauma. In this long journey, we focus on highlighting best practices of Indigenous self-determination in disaster recovery. These include providing culturally appropriate, community member-led services to address the physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional needs of evacuees throughout disaster displacement.

The unnatural disasters of colonialism and displacement

Indigenous Peoples have lived on the land now known as Canada since time immemorial. However, the past 400 years of colonization in Canada can be understood as a political ideology that legitimated the modern European invasion, occupation, and exploitation of inhabited Indigenous lands and devastated Indigenous culture (Coates, 2004). To meet the perceived economic and political needs of imperial powers, colonization was rationalized as a way to bring Christianity and ‘civilization’ to Indigenous Peoples by universalizing a specific set of European beliefs and values (Deloria, 1969; Howe, 2003; McMillan & Yellowhorn, 2004).

The enduring and unnatural disaster of colonialism in Canada has been catastrophic for Indigenous Peoples. Rapid depopulation and pervasive forms of physical, mental, and social abuse contributed to substantial losses of identity, language, cultural practice, spiritual belief, and territory (Howitt et al., 2011). As a mechanism for furthering the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples, in 1876, the federal government of Canada developed the Indian Act, bringing a coordinated approach to ‘Indian policy’. With the intent of assimilation—the erasure of Indigenous Peoples as distinct nations—the priorities of the Indian Act addressed three main areas of legislation: land, membership, and local government (Morris, 1880; Reading and Wien, 2009). As explained by Duncan Campbell Scott, Indian Affairs Deputy Minister from 1913 to 1932, “our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole objective of this bill” (TRCC, 2015, p. 54).

For Indigenous Peoples in Canada, colonialism represents a painful chronicle of broken treaties, stolen lands, Indian residential schools, and the Indian Act. Of vital note to this case study is the way the Indian Act undermined the ability of Indigenous communities to self-govern and gave the federal government the authority to strip the power of chiefs and councillors and overturn decisions made by band councils. As the legislation became further entrenched, the government also began to assume greater authority over how reserve lands could be allocated (Reading & Wien, 2009; TRCC, 2015). Under this paternalistic approach, entire reserves were relocated against the will of communities.

Forced relocation disrupted Indigenous settlement patterns that accommodated seasonal opportunities and hazards (e.g., winter villages were often located in areas of refuge from winter storms and other seasonal hazards). Traditionally, many Indigenous communities lived in multiple settlement sites that were utilized at different times of the year (Dicken, 2017). The selection of these sites was dependent on seasonal hunting and fishing practices and environmental factors such as weather and access to fresh water. Through the Reserve section of the Indian Act, however, communities were forced to settle and remain in one location. Although many Indigenous communities did not surrender their land, through federal legislation the Canadian government created small reserves for each community in the late 19th century. By limiting access to land, this act also curtailed hunting and fishing, which essentially deprived Indigenous Peoples of food security and economic viability.

Today, much of the reserve land across Canada is exposed to and experiences a disproportionate level of risk and hazards compared to their neighbouring non-Indigenous communities, and lacks the flood protection infrastructure such as dikes needed to mitigate this risk (Yumagulova, 2020). This is due to historical and present-day complexities associated with lack of infrastructure, marginalized lands, and other socio-economic factors (OAGC, 2013). The establishment of reserves caused land displacement (the forced relocation from and the loss of traditional lands, and/or loss of access to traditional lands) and environmental dispossession (the process through which traditional access to the resources of the environment is reduced though displacement, environmental contamination, unprecedented resource extraction, or land rights disputes), both of which are detrimental to the health and wellness of Indigenous communities (Lewis et al, 2020).

Disproportionate levels of risk in Indigenous communities

First Nation communities are 18 times more likely to be evacuated due to disasters than people living off-reserve and fire-related death is more than 10 times higher (Government of Canada, 2019). Disaster displacement impacts are further compounded due to gaps in emergency management practices such as lack of evacuation preparedness (Asfaw et al., 2020) and insurance gaps (Public Safety Canada, 2020); meanwhile, lack of self-determination in disaster response can result in externally imposed emergency management practices, further deepening marginalization, trauma, and conflict within communities (Yumagulova et al, 2019a). More than a fifth of residential properties on Indigenous reserves are exposed to risks of one-in-a-hundred-year flooding (Thistlethwaite et al, 2020). Inadequate housing further exacerbates social vulnerability: the proportion of First Nations people with registered or treaty Indian status who lived in a dwelling that needed major repairs was more than three times higher on reserve (44.2%) than off reserve (14.2%) (Statistics Canada, 2016). For more information, see Yumagulova, Yellow Old Woman-Munro, MacLean-Hawes, Naveau, Vogel, 2021.

Through disasters such as flood and fire, standard emergency management practices can inadvertently bring about forced evacuation or relocation for the purposes of public safety. Both evacuation and relocation negatively impact community resilience and can cause irreparable damage to members of Indigenous communities when they become separated from their traditional lands (Howitt et al., 2012). Forced evacuation, in concert with colonial legacies associated with loss of land, speaks to the urgent need for pre-disaster recovery planning that supports the cultural needs of Indigenous Peoples, informed by both historical and present-day needs.

First Nation communities are 18 times more likely to be evacuated due to disasters than people living off-reserve.

Shaped by Canadian history and entrenched in present day society, colonialism remains an ongoing process, with continuous influence on both the structure and the quality of the relationship between Canadian settlers and Indigenous Peoples. To explore the experiences of colonial displacement from land and the present and future state of climate impacts, we draw on lessons from the flooding of the Siksika Nation and the wisdom with which they have responded and recovered.

Climate change and disaster displacement

Climate change presents unique challenges for Indigenous Peoples, exacerbated by historical and ongoing processes of land dispossession. Climate change can further exacerbate political and economic marginalization, loss of land and resources, human rights violations, discrimination, and unemployment (International Labour Organization, 2017). Indigenous communities in Canada are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to Indigenous People’s intrinsic connection to and reliance on their traditional territories (e.g., for sustenance through rights to hunt and fish), remoteness in relation to access to essential services, infrastructure deficits, and exposure to climate risks (CIER, 2009; CIER, 2020). Both disaster and climate displacement present unique challenges for Indigenous Peoples given their dependence upon, spiritual connections to, and identity-forming relationship with the land—a relationship grounded in intergenerational place attachment that extends over millennia (Middleton et al, 2020). Evidence collected by Indigenous scholars and community members suggests that even well-intentioned emergency management practices, if externally imposed and culturally unsafe, can further deepen marginalization, trauma, and conflict within communities, exacerbating disaster impacts and pre-existing vulnerabilities (Yumagulova et al, 2019a; CIER, 2019). And the urgent need to adapt to climate change can resurface previous traumas for some Indigenous Peoples (Middleton et al, 2020).

The history of Siksika Nation

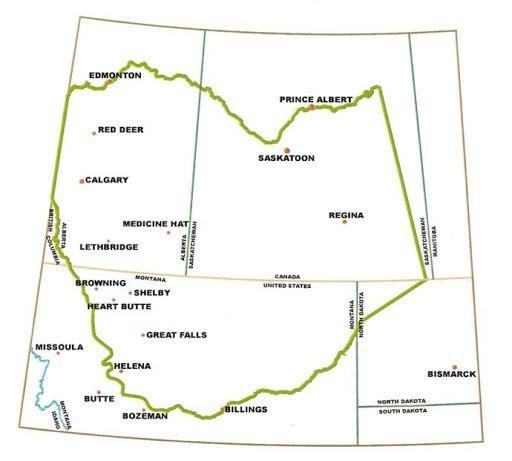

The Siksika Nation is located 87 kilometres southeast of Calgary and is the second-largest Indigenous reserve in Canada with a land area of 696.54 square kilometres and a total population of over 7,500. The Siksika are a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, which also includes the Piikani and Kainaiwa of southern Alberta and the Blackfeet in the State of Montana (Siksika Nation, 2020a). The traditional Blackfoot territory includes northern Montana and North Dakota, and extends north as far as Edmonton in Alberta and Prince Albert in Saskatchewan (see maps).

Traditionally, Iiníí (Buffalo in Blackfoot language) was the way of life for the Blackfoot as a source of sustenance and spirituality. Iiníí took care of the Blackfoot Peoples by providing lodging, clothing, and food. It was the foundation of spiritual and social relationships and it guided the nomadic Blackfoot Peoples across their vast traditional territories. Families were central to the Siksika way of life and extended family systems nurtured shared responsibility. Traditional governance and leadership roles included such prerequisites as the individual’s capacity to share and care for all people, especially the very young and the aged (Siksika Nation, 2020b).

Prior to the 1800s, the Siksika Government structure was made up of 36 clans with a total population of 18,000. By 1890, the North Blackfoot population had been decimated by the introduction of disease from Europe, falling to approximately 600 to 800 members (Siksika Nation, 2020b).

In 1877, Isapo-muxika (Chief Crowfoot), the legendary leader of the Siksika, signed Treaty 7, which forced the Siksika to a reserve at Blackfoot Crossing, east of Calgary (Siksika Nation, 2020b). The nomadic way of life was forever changed and some Siksika members became farmers, ranchers, and coal miners on the reserve (Dempsey, 2019).

Reserves ended traditional ways of life. The Blackfoot Confederacy struggled to survive on reserves without the ability to hunt buffalo. The winter of 1883–84, the “starvation winter,” brought widespread hunger (Siksika Nation, 2020b; Dempsey, 2019).

In 1910, facing pressure from the federal government and developers, the Siksika surrendered a significant portion of their reserve for sale, an agreement that was detrimental to the Nation. The funds were held in trust by the government for administering the construction of new homes and other activities on reserve (Dempsey, 2019).

The modern day Siksika Peoples continue to advocate for autonomy and self-government that is rooted in the land. The traditional territory and its diverse land had many uses for the Blackfoot Peoples. For example, the Miistukskoowa located within the area now known as Banff National Park were part of the Blackfoot’s traditional territory used for winter camps and harvest of timber for tipis. In 1908, the land was taken from the Siksika without consent or proper compensation. The Castle Mountain Settlement, reached in 2017, provided financial compensation, economic opportunities inside the park, and ongoing access to the land for Siksika Peoples (Government of Canada, 2017). It took 57 years to settle the agreement. Under the settlement, the Siksika Nation has the option to purchase on the open market up to 17,491 acres of land outside of the boundaries of Banff National Park and apply to Canada to have the lands added to its reserve (Government of Canada, 2017).

The 2013 flood disaster in Siksika Nation

In June 2013, eight communities along the Bow River, which flows west to east within the Siksika Nation, were devastated by a flood. Two main bridges and 171 homes were damaged by the flood, with over 1,000 people displaced from their homes (Yumagulova et al., 2019a). Recovery has been an ongoing process, with some of the community members still displaced from their home at the time of the interviews (spring-summer 2019), six and a half years after the event. To describe the long-term impacts of the flood on the community, we draw on Darlene’s reflections as the Director for Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre and community interviews conducted by Darlene with the flood evacuees six years after the disaster (Yumagulova, Yellow Old Woman-Munro, Dicken, 2019b).

Environmental and land-use changes have brought new flood risks to Siksika. There is no historical record or living memory of a flood disaster of similar magnitude on Siksika lands. As Siksika Elder Darlene reflected:

“My mother would say the biggest event prior to this flood was around 1948. The community, my parents and other families lived along the river, it was in the spring, and my mother had told me they had big icebergs flowing right through the communities. In those days, we had cabins or smaller homes so the icebergs that floated overland totally destroyed some homes. All they could do was to move up the hill, which wasn’t too far from their home, but they were devastated to see their homes, in those days too, get destroyed. But since the 40s there was nothing major, as far as flooding. And everybody went back to living in the valleys, including us.”

Over the coming decades, climate change is projected to further increase the frequency and magnitude of flooding across Alberta (Zhang et al., 2019).

A long road home: Five phases of disaster displacement

Phase 1: Initial response from evacuees – confusion and makeshift housing (June 21–end of June, 2013)

Immediately following the flooding on June 21, 2013, evacuees lived in tents, RV’s, teepees and makeshift shacks close to the community they fled due to the flood, and due to the lack of adequate lodging and infrastructure in the area. Many people did not want to leave their homes unattended due to incidents of looting, and as a result, sought refuge as close to their homes as possible. This initial time was described as deeply challenging by the majority of the evacuees who lost their homes. As a single parent with children with disabilities described:

“It was my sanctuary, my home…where I raised my children; the only thing I had was my vehicle and what we could pack in the vehicle and then we left, so we had to start all over. The most difficult was seeing all the people and our — as a Nation, lose what was personal to them, you know; a place to lay their head, a roof over their home, how to provide with their food and how to provide on a day-to-day basis…people didn’t understand where to go, or when to go, what to do.”

Phase 2: Hotel lodging and gaps in access to services (July–August, 2013)

Inclement weather following the flood meant that evacuees had to move to hotels. Once the flooding subsided, additional supports started to arrive; however, the information about the supports that became available following the flood did not reach those who needed them the most. Sometimes this information was only shared through social media, a platform that was challenging to access for Elders and the chronically ill. For others it was family members that brought them the information.

The impacts of losing a home were particularly hard for single parents who had children with special needs due to the children’s difficulty understanding the complexities of relocation and loss of home. As a single parent with a teenager with Down syndrome described:

“…[they are] non-verbal so [they are] used to a lot of structure. [The flood] threw us out of our routine, our daily routine, our daily living life, and it was stressful …when we were coming ‘home’, we had no home to come to, so it was tougher for [them] to understand. [They] did take it hard, wanting to come home but I had to explain ‘No, we’re going to stay over here for now’. I wasn’t able to have an ATCO trailer home just because I was away for school [off reserve], when I came back, they were all full. Thank God I had family that opened their doors towards us and took us in for the time that we were out of a home.”

Phase 3: ATCO trailers (September 2013–2015)

As part of the recovery process, evacuees were moved from hotels to ATCO trailers (modular mobile office trailers often used as temporary accommodations for resource industry workers) at three different sites. All of the trailers were used and had numerous issues that made them unsuitable for families and children. Problems included unreliable heating, no cooking was permitted in the units, there were no refrigerators to store food, and there were no retrofits available for people with mobility challenges or special needs. Each unit had one small double bed, a place to hang coats and jackets, a small dresser, a washroom, and a television in each room.

Community members found the environment very controlled and made complaints such as, “It is like residential school all over again, regimental environment,” and “My children are not safe, their rooms are down the hallway therefore we must constantly ensure they are safe.” There were curfews, and security check-ins each time they left and returned to the ATCO sites. One interviewee said, “I just felt like I’m in prison there, so I get up in the mornings, I eat and then I’m gone maybe till supper or sometime then I go back.”

A single parent who was displaced expressed concern that the ATCO trailers were not suitable for people with disabilities. Some of the highly vulnerable members of the community had to move off-reserve to accommodate the special needs that were not being met in temporary housing, which further displaced them from their home community and removed them from services that were being provided.

“We couldn’t go in [ATCO trailers] because my son is in a wheelchair, so we ended up in Strathmore. We kind of moved from [one motel] to the other one there next to it. Then they couldn’t accommodate us because there was no elevator there. So, we finally ended up at [another motel]. We were actually there for almost a year and a half… For a while there, my kids were being transported by Siksika disability, until the Board of Education couldn’t do it anymore because they said we were off the reserve… So, Disabilities took over and they started taking my kids to school.”

Phase 4: New Temporary Neighbourhoods (Starting June 2016)

After approximately 18 months at the ATCO sites, two-thirds of the community members affected by the flood (in total, 771 people were forced into temporary housing (Jarvie, 2016)) were moved again to the New Temporary Neighborhoods (“NTN’s”). Their new housing was again trailers and again identified as substandard quality. In the NTN’s, one service provider identified an increase in substance abuse and vandalism:

“[the evacuees] were highly monitored in the ATCO trailers, because of security guards and people would be asked to leave if they were caught drinking. But once they moved into the trailers, it just seemed like – people were already struggling with alcohol, and it became worse. And you started to see lots of other stuff surface: violence, the vandalism.”

The vandalized NTNs further reduced the housing stock available: “[Of the] 120 NTNs that came, about 30 of them were vandalized so no one’s living in [them] right now.”

The trailers brought a strong feeling of isolation for families and communities. Some of the families only stayed in NTNs for a few months as the larger families got split apart. As a result, managing and paying for utilities became unaffordable for many families:

“You’ve got to remember that some of these families—we could have had four families in one house, and when the flood hit those families in that one house, those three other families got their own unit. And when they got their own unit, some of them were ‘this is the first time I’m on my own, I am now responsible for the home’ and they couldn’t maintain that.”

As of June 2016, only 13 new permanent homes had been built, while more than 600 people were still living with family, friends, temporarily repaired houses, or in one of the 144 NTN trailers (Patrick, 2017).

Phase 5: Still searching for home after disaster displacement (Starting in 2017)

At the time of the interviews, it had been six years since the flood, yet the journey home was still ongoing for some evacuees. Some evacuees had moved back into their old homes, other families were still moving into their new houses. For some of the evacuees that lost their homes and had to move off reserve to accommodate special needs of vulnerable family members, returning to the community was a challenge: “We’re not on the map on the reserve, so they’re having a hard time relocating all the people that moved.”

Some of the evacuees that were eventually able to return to their homes noted significant mould, flooded basements, and drinking water issues following the flood. Numerous house deficiencies had to be fixed after the flood: “They had moved into their new home [and] the water was not tested right and so they had to be retested and the water lines had to be re-dug, because they didn’t do the proper testing.”

For others, moving into their new homes took a long six and a half years following the flood. Due to poor workmanship, most of these community members are experiencing issues with their new homes. These continuing challenges include windows installed backwards, stairways that do not meet the code and houses built without wood stoves meaning a cost-intensive transition over to electric baseboards.

Although flood waters have long receded and new housing is available, disruptions to sense of place and of home have not gone away. This speaks to the importance of understanding what “returning home” really means and of the trauma and grief that is bound within the impacts of climate-related disasters.

Reflections from an Elder: What we have lost due to the disaster

The flood disaster further dispossessed the community of land, culture, sense of safety, and traditional ways of life.

Loss of land: It is estimated that a quarter of the Siksika land base has been lost or is now uninhabitable due to the flood. There were three communities that were affected by the flooding, about a thousand homes, and many families. Darlene reflected that most community members are not happy where they are now. In one community, the community members did not have any input into their relocation and recovery: decisions were made by the disaster recovery committee and the leadership regarding where the communities would be located. She identified that every time there is a disaster, more people are being moved into smaller areas where there remains a potential and risk for other disasters to occur.

Loss of sense of safety: A major highway runs through Siksika lands, so when post-flood community rebuilding occurred, the disaster recovery committee used the road as the central infrastructure to rebuild the community around. This choice has resulted in further trauma to the communities, as Darlene reflects on the many deaths that have occurred along the highway. She further states, “the individuals who agreed to build more houses did not negotiate to ensure the highway was safe for children and people who didn’t have transportation and walk down that highway. Darlene believes Siksika leadership is in negotiations with Alberta Transportation to install lights and post reduced speed limit signs. But for many families, there is the reality of compounding grief, trauma, and loss as several community members have been killed on that highway by semi-trucks, many of which were not adhering to speed limits. The current speed limits through the community are set at 80 km/hr, but Darlene identified that the community is advocating for further reductions, so semi-trucks and other vehicles do not speed through the community. This shows that the recovery process can introduce further risks through rebuilding, especially when the options for relocation sites are limited.

The trauma of disaster: The trauma of disaster carried on long after the flood waters subsided, especially for the children, as shared by one of the interviewees: “When vehicles drive by, [the grandparents, parents and grandchildren] hear a rumbling. Is that the river coming through the trees? We would jump up and look out at night with a flashlight, just to see if water was coming again. And [children] would have all these continuous dreams of flooding again and that fear of the flood coming through.” In interview after interview, community members spoke of re-traumatization, fear of the unknown, increased stress levels due to the need to pack up and move belongings, feelings of loss each time they moved, depression, sadness, and loss of income due to employment disruptions during displacement.

Loss of access to traditional medicines and foods due to contamination of water, soil, and silting: The flood also caused contamination of water and soil. This resulted in reduced access to traditional seasonal foods and medicines, especially for the elderly, who relied on these medicines for their well-being. As one service provider suggested: “Seasonal harvests – the berries, the mints, and the medicines – some of the people that would pick in these areas didn’t want to pick anymore. They didn’t know how long they were to wait. Someone told them they should wait five years, but people were still scared.” As climate change contributes to more frequent and severe flooding across the Siksika territory, this disruption to accessing traditional medicines and food will have devastating cultural consequences.

Several interviewees also raised their concerns about contaminated soils that the new sites were built on. As Darlene shared:

“The one community which is referred to as Washington, they lived in a valley on the east end along the Bow River. The newly built Washington community members were moved onto land that was previously farmland, and we all know that the farmers sprayed onto the fields. My biggest concern is, how could they move this whole community on land that is possibly contaminated. There’s been evidence of that in our community before where houses were built on farmland and those families had died from cancer. They did not remove the topsoil; they just built their houses right on the existing soil. There are a lot of environmental issues that nobody pays attention to, we need to teach our youth regarding possible contaminants within our community and possible disasters due to climate change.”

Loss of home community and traditional way of life: It was not only homes that were lost in the flood, but entire communities and a way of life. Some of the evacuees engaged in a peaceful protest over the relocation process that did not consider their concerns. Led by Ben Crow Chief, the community members established a blockade of a new permanent housing subdivision near an existing NTN that lasted over 226 days (Jarvie, 2016). The community members wanted to reside on traditional clan lands or near where they had lived before in low-lying flood prone areas. A band member (who declined to be named for fear of loss of work on the reserve) commented in Aitsiniki, Siksika Nation’s newspaper: “When you create these big subdivisions with people living on top of each other, that’s when you have all the social problems. This is not how we traditionally live (Jarvie, 2016).” Concerns about crime and disrupted clan structures were also raised (Jarvie, 2016; Patrick, 2017).

Self-determination and disaster recovery

Cultural continuity, or “being who we are,” and self-determination, or “being a self-sufficient Nation” (Oster et al, 2015), are foundational to Indigenous community resilience. Several key cultural continuity initiatives connected the evacuees to their culture, serving as their ‘home’ by creating culturally safe spaces throughout the phases of displacement.

Historically, the Siksika way of life for families, friends, and neighbours can be summarized in a Blackfoot word ispommitaa (help out, assist). Ispommitaa connects members of the community with each other, revitalising co-operative cultural traditions and creating a sense of belonging through participation in shared events and through crises (Yumagulova et al, 2019a). These Indigenous community-held values became the foundation of flood recovery and community care throughout the displacement.

One particularly unique Siksika organization, the Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre (DDDRC), focused on “rebuilding families and communities through hope and healing” (Siksika Nation, 2014). The Centre consisted of a multi-disciplinary group of Siksika professionals, youth, and a Siksika traditional Elder. The team assisted the evacuees on their journey to recovery by providing culturally safe supports and services for physical, mental, and social well-being. The diverse professional background, experience, and knowledge of this team ensured that the multiple needs of the evacuees were addressed in one place, as a centralized service, instead of having to visit multiple departments. The other unique feature was that the team provided these services within the temporary housing of the evacuees, thus serving as a critical link for cultural continuity between the community and changing housing locations of the evacuees. An Indigenous service provider stressed the importance of this ability to meet people where they were at:

“Meeting the people in their own homes, their temporary situations, temporary housing, hotel or trailers…it allowed for a lot more trust building that people would be willing to open their doors to you, to be able to be seen in that situation, you know? I think it was more of a cultural thing. It’s like, you went home – you went to visit these people in their homes. Rather than them seeing you as a psychologist or as a professional coming to do counselling, they saw me more as somebody coming in to visit and checking in on them. In a much safer, non-intrusive way, you know?”

Meeting the evacuees in their temporary homes and proactively delivering services based on established trust and relationship by Blackfoot-speaking professionals was a culturally safe practice that met the needs of the most vulnerable (such as elderly, chronically ill, and children with disabilities).

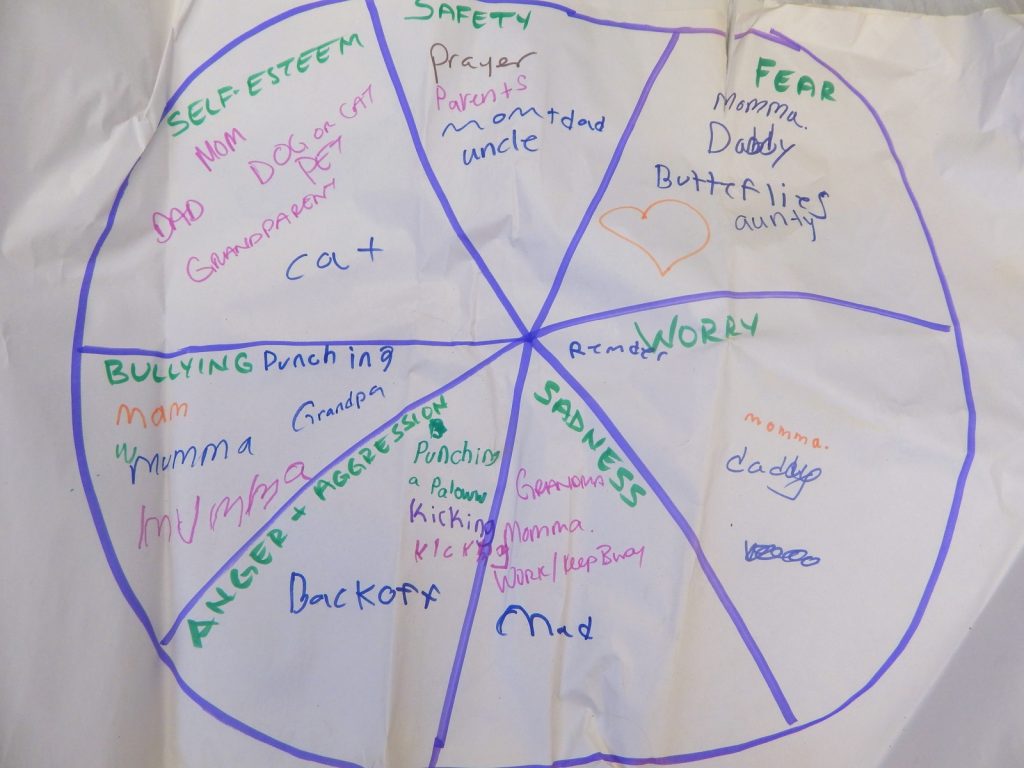

By being the boots and the eyes on the ground, the centre staff were able to respond to community-identified gaps in recovery such as the impacts of disaster displacement on children. Throughout the early phases of displacement, there were reports of children misbehaving in schools, exhibiting anger through the destruction of property at the ATCO sites, and later at the NTNs. In collaboration with Save the Children, training on assessment and appropriate activities for children who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was provided to the various youth workers within Siksika. DDDRC youth commenced youth programs at the three ATCO sites such as art therapy, cultural craft (making hand drums), parfleche (buffalo hide) bags, and outdoor activities in the spring and summer to pick and identify various medicinal plants and berries. The programs continued for two to three years into recovery as the DDDRC changed locations.

By providing culturally appropriate, community member-led services to address the physical, mental, and social needs of evacuees throughout the various phases of displacement, DDDRC serves as a model of self-determination in a post-disaster recovery context that could be used in other Indigenous communities.

Conclusions

The Siksika case study shows the disproportionate impact of climate change on Indigenous communities due to climatic and non-climatic factors (social, economic, cultural, political, and institutional inequities).

This case study acknowledges that disasters and climate change impacts in Indigenous communities need to be understood within the context of targeted risk creation through colonial and racist policies of land dispossession, cultural erasure, and destructive actions such as the residential school system and the Indian Act.

The stories shared by Siksika evacuees shows that disaster displacement has multiple stages, and that recovery is an ongoing process with uncertain outcomes. Six long years after the disaster, some of the evacuees had not returned to their homes, while many others did not feel safe in their new homes and experienced fear and increased stress due to inclement weather (e.g., increased rain, wind, and wildfires).

Through this case study we challenge a widely used notion of a “natural disaster.” When examined from an Indigenous community perspective, and bearing in mind targeted long-term risk creation through colonial land dispossession combined with anthropogenic climate change, there is very little that is “natural” about flooding disasters in First Nation communities.

Our case study shows examples of wise practices for community-led and culturally safe responses to disasters through the Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre. It is evident that community organizations engaged with long-term Indigenous-led disaster recovery can address the gaps in supporting physical, mental, cultural and spiritual health needs of displaced Indigenous peoples.

This case study is in part based on Yumagulova L, Yellow Old Woman-Munro D, Dicken E. (2019b) report titled “Honouring the Voices of Long-Term Evacuees Following Natural Disasters in Ashcroft Indian Band and Siksika Nation”. Data for this project was collected under University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board HS22640 (H20019:096) “Long-term Public Health Responses to Evacuation Due to Natural Disaster in Canada.” Production of this report was possible in part due to a financial contribution from the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health. The views herein do not necessarily represent the views of the NCCs or the Public Health Agency of Canada.

About the authors

Darlene Yellow Old Woman-Munro is a Siksika Elder born and raised on the Siksika Nation; she is the oldest of 10 children. Darlene has served her community through many roles as a community nurse, Treaty 7 Zone Director, Medical Services Branch and Chief. In 2013, Darlene came out semi-retirement to assist Siksika Nation with the flood disaster as a night shift volunteer and became Manager of Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Program and Project Manager for Community Wellness (Psychosocial) Recovery Program.

Dr. Lilia Yumagulova is a Bashkir woman with degrees in engineering and risk analysis and a PhD in resilience planning. Lilia’s passion is in building community resilience to climate change and disasters. With over 20 years of work experience with government, NGOs, media, Indigenous communities and supranational organizations in Europe and North America, Lilia is the Program Director for the Preparing Our Home Program that empowers Indigenous youth leadership in community resilience.

As an Indigenous scholar and practitioner in Emergency Management, Dr. Emily Dicken has over 15 years of experience and has held roles in organizations such as North Shore Emergency Management, First Nations Health Authority and Emergency Management BC. Across all areas of her work, Emily seeks to understand colonialism as an unnatural and enduring disaster impacting Indigenous communities. When not working, Emily can be found enjoying time in the Coast Mountains with her husband Jeff and their two young sons, Keegan and Bowen.

References

Asfaw, H.W., et al. 2020. “Indigenous Elders’ Experiences, Vulnerabilities and Coping during Hazard Evacuation: The Case of the 2011 Sandy Lake First Nation Wildfire Evacuation.” Society and Natural Resources: 33(10), pp. 1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2020.1745976

Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources, CIER. 2009. Climate Risks and Adaptive Capacity in Aboriginal Communities. http://www.yourcier.org/climate-risks-and-adaptive-capacity-in-aboriginal-communities-an-assessment-south-of-60-2009.html

CIER. 2019. Gathering for Health and Cultural Safety During Evacuations. Prepared for Indigenous Services Canada.

CIER. 2020. Climate Change Adaptation Planning Toolkit for Indigenous Communities.

http://www.yourcier.org/climate-change-adaptation-planning-toolkit-for-indigenous-communities.html

Coates, K. 2004. A Global History of Indigenous Peoples. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dicken, E. 2017. Informing Disaster Resilience through a Nuu-chah-nulth Way of Knowing. University of Victoria. Retrieved from https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/8935/Dicken_Emily_PhD_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Deloria, V., Jr. 1969. Custer died for your sins: An Indian manifesto. New York: Macmillan.

Dempsey, H. 2019. “Siksika (Blackfoot).” In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/blackfoot-siksika

Government of Canada. 2017. Canada and the Siksika Nation Advance Reconciliation with Signing of Castle Mountain Settlement. https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs/news/2017/01/canada-siksika-nation-advance-reconciliation-signing-castle-mountain-settlement.html

Government of Canada. 2019. “Budget: GBA+: Chapter 3.” Redressing Past Wrongs and Advancing Self-Determination.

Howe, S. 2003. Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Howitt, R., Havnen, O., & Veland, S. 2012. “Natural and Unnatural Disasters: Responding with Respect for Indigenous Rights and Knowledge.” Geographical Research. 50(1): 47-59.

Howitt, R. 2020. “Unsettling the taken (for granted).” Progress in human geography, 44(2), 193-215.

Insurance Bureau of Canada. 2021. “Severe Weather Caused $2.4 Billion in Insured Damage in 2020.”

http://www.ibc.ca/on/resources/media-centre/media-releases/severe-weather-caused-$2-4-billion-in-insured-damage-in-2020

International Labour Organization. 2017. Indigenous peoples and climate change: From victims to change agents through decent work. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—gender/documents/publication/wcms_551189.pdf

IPCC. [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf

Jarvie, M. 2016. “Siksika Members Still Waiting for a Home Three Years After the Flood.” Aitsiniki—Siksika Nation’s Newspaper. Vol. 25 Issue 6. P. 3.

Lavell, A., & Maskrey, A. 2014. “The future of disaster risk management.” Environmental Hazards, 13(4), 267–280. http://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2014.935282

Lewis, D., Castleden, H., Apostle, R., Francis, S., & Francis‐Strickland, K. 2020. “Linking land displacement and environmental dispossession to Mi’kmaw health and well‐being: Culturally relevant place‐based interpretive frameworks matter.” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cag.12656

McMillan, A. & Yellowhorn, E. 2004. First Peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & MacIntyre.

Middleton, J., Cunsolo, A., Jones-Bitton, A., Wright, C. J., & Harper, S. L. 2020. Indigenous mental health in a changing climate: A systematic scoping review of the global literature. Environmental Research Letters, 15(5), 053001.

Morris, A. 1880. “The Treaties of Canada.” Toronto, Canada: Belfords, Clarke & Co.

Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAGC) (2013). Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada. Chapter 6 – Emergency Management on Reserves. Retrieved from https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/att__e_38848.html

Oliver-Smith, A., Alcántara-Ayala, I., Burton, I., & Lavell, A. M. 2016. “Forensic investigations of disasters (FORIN): A conceptual framework and guide to research.” IRDR: Beijing. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291349173_Forensic_Investigations_of_Disasters_FORIN_a_conceptual_framework_and_guide_to_research

Oster, R. T., Grier, A., Lightning, R., Mayan, M. J., & Toth, E. L. 2014. “Cultural continuity, traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta First Nations: a mixed methods study.” International journal for equity in health, 13(1), 1-11.

Patrick R. 2017. “Social and cultural impacts of the 2013 Bow River flood at Siksika Nation, Alberta Canada.” Indigenous Policy Journal. 28(3). http://www.indigenouspolicy.org/index.php/ipj/article/view/521/504.

Public Safety Canada. 2020. “Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation.” https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/mrgnc-mngmnt/dsstr-prvntn-mtgtn/tsk-frc-fld-en.aspx

Reading, C & Wien, F. 2009. Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. The Senate Sub-Committee on Population Health.

Siksika Nation. 2014. Dancing Deer Disaster Recovery Centre Public Information http://siksikanation.com/wp/dancing-deer-disaster-recovery-centre-public-information/

Siksika Nation. 2020a. About Siksika Nation. http://siksikanation.com/wp/about/

Siksika Nation. 2020b. History and Culture. http://siksikanation.com/wp/history/

Statistics Canada. 2016. The housing conditions of Aboriginal people in Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016021/98-200-x2016021-eng.cfm

Thistlethwaite, J., Minano, A., Henstra, D., & Scott, D. 2020. “Indigenous Reserve Lands in Canada Face High Flood Risk. Policy Brief No. 159 — April 2020.” Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRCC). 2015. Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume One: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Toronto, ON: Lorimer.

Yumagulova, L., Suzanne Phibbs, Christine M. Kenney, Darlene Yellow Old Woman-Munro, Amy Cardinal Christianson, Tara K. McGee & Rosalita Whitehair. 2019a. “The role of disaster volunteering in Indigenous communities.” Environmental Hazards. DOI:10.1080/17477891.2019.1657791

Yumagulova L, Yellow Old Woman-Munro D, Dicken E. 2019b. “Honouring the Voices of Long-Term Evacuees Following Natural Disasters in Ashcroft Indian Band and Siksika Nation.” National Collaborating Centres for Public Health. May 2020. (NCCPH Internal report, unpublished).

Yumagulova, Yellow Old Woman-Munro, MacLean-Hawes, Naveau, Vogel. 2021. “Building Climate Resilience in Indigenous Communities.” Preparing Our Home. http://preparingourhome.ca/climate-resilience-in-first-nation-communities/

Yumagulova, L. 2020. “Disrupting the riskscapes of inequities: a case study of planning for resilience in Canada’s Metro Vancouver region.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(2), 293-318.

Zhang, X., Flato, G., Kirchmeier-Young, M., Vincent, L., Wan, H., Wang, X., Rong, R., Fyfe, J., Li, G., Kharin, V.V. 2019. “Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Across Canada”; Chapter 4 in Bush, E. and Lemmen, D.S. (Eds.) Canada’s Changing Climate Report. Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, pp 112-193.