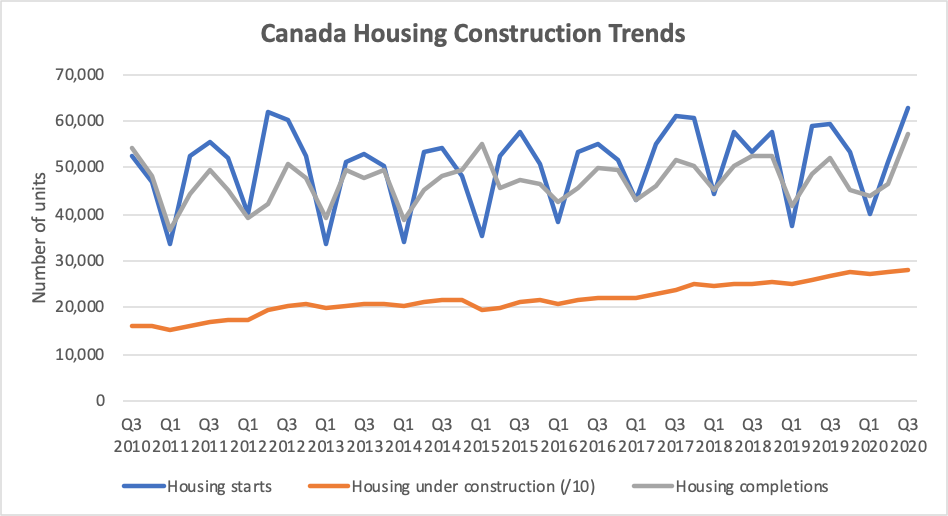

In the third quarter of 2020, Canada had more homes under construction than during any quarter in the last decade. Yes, you heard right. Although Canada’s annualized GDP dropped 39 per cent due to the COVID-19 in the second quarter of 2020, Canada is continuing to pour money into real estate.

But here’s the real kicker: Without both flood maps and land use planning across much of Canada, no one is stopping those new homes from being built in places that will flood.

And when those floods happen, the effects could ripple throughout the entire economy. Worse, climate change is making those flooding events more likely than ever.

(Click on the graph to enlarge)

Flooded fortunes

Vancouver is at the epicentre of the current real estate boom. Between 2017 and the fall of 2020, the City of Vancouver granted 22,697 building permits, 23 per cent of which were for new builds. The value of these new builds, counting materials and labour, totalled $10.6 billion—an average of about $2 million per new build during the period (including multi-unit buildings like condos).

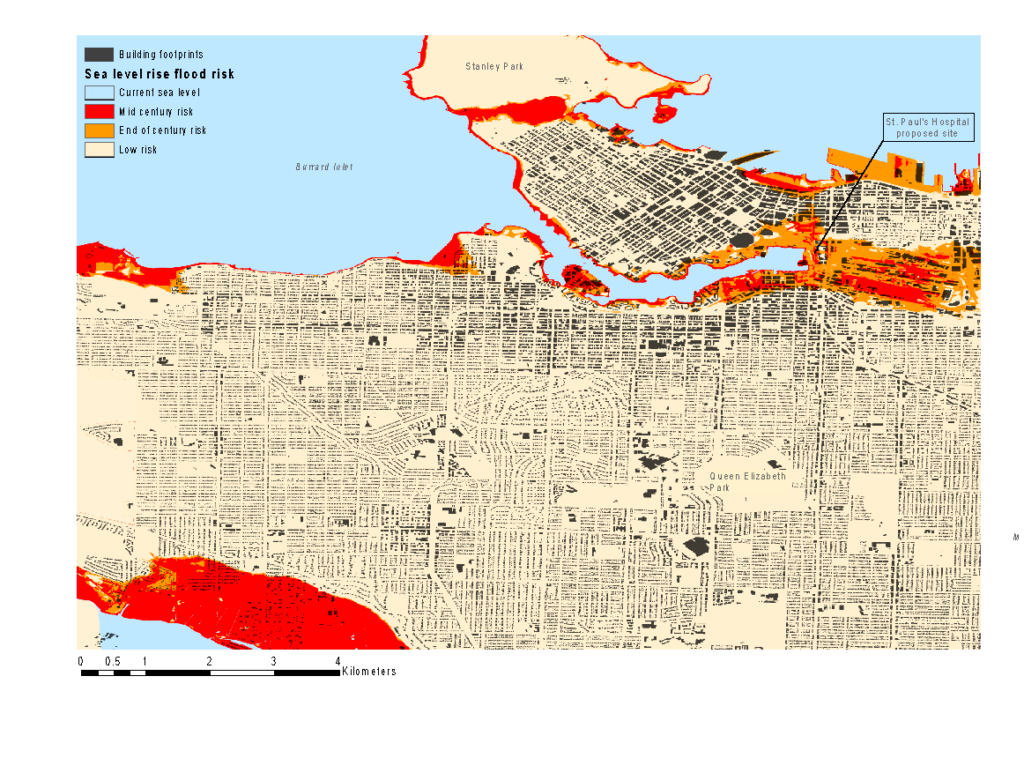

We overlaid these new builds over flood risk zones and found that a large number are in locations with a high risk of flooding. In the past three years, 10 per cent of the building permits for new builds in the City of Vancouver were located within a 100-year floodplain, with a value of $1 billion (1).

Building in flood zones is nothing new in and around Vancouver.

Of the estimated 106,900 buildings in the entire City of Vancouver, about 10,000, or nine per cent, are within a 100-year floodplain. An additional 4,000 buildings, or 3.7 per cent, will be at high risk of coastal flooding in 50 years. Across Metro Vancouver–which includes the City of Vancouver plus 21 other municipalities and one First Nation reserve–the Fraser Basin Council estimates over 200,000 people would be displaced in the event of a 1 in 500-year flood. Insurance companies and engineers know the risks, but policies have been slow to reflect the mounting dangers. In 2014, the City of Vancouver rolled out limits to new development in high-risk coastal areas. The policy has helped limit new construction in areas that will be under sea level in 2100; only one per cent of new builds between 2017 and fall 2020 were within high-risk coastal zones (most flood risk was from stormwater and river flooding). But the policy has loopholes and does not capture all flood risk. And without transparency the market is not able to efficiently factor in risks.

(Click on the graph to enlarge)

The City of Vancouver is exposed to sea level rise. However, governments and markets continue to place money in high-risk locations. This map shows existing building footprints using data from Bing. The lands shown in this map are the traditional and unceded territory of Coast Salish Peoples, including the territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Selilwitulh Nations.

Neglecting flood risk will have implications for the services on which communities depend. One of the largest hospitals in Vancouver, St. Paul’s hospital, is being relocated in the coming years. The new site is within a high-risk flood zone where the City of Vancouver restricts development. To comply with the flood by-laws, engineers plan to raise the lot by at least a meter for the $1.9-billion facility. Raising the lot may protect the hospital, but it won’t protect the surrounding area–which will house over $6 billion in additional hospital infrastructure.

Regular flooding is already reality for communities across Canada, and climate change will make it a reality for many more. Yet cities and towns across Canada continue to build in high-risk areas, putting houses, businesses, and infrastructure at risk of severe damage and loss.

Up a creek without a paddle

So, flood risks matter for some property owners. But what about everyone else? Do flood risks matter for people who do not live or work in one of Vancouver’s floodplains? The answer is a resounding yes.

What seems like a local problem is actually an economy-wide problem. From July to September of 2020, for example, over $17 billion was invested in homes across Canada. The majority of the risk was secured by taxpayers through the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). By securing mortgages, the Government of Canada guarantees banks that if a home is destroyed, and property insurance and owners cannot pay back the debt, taxpayers will cover the loss. The insurance industry also faces mounting pressure, as claims related to flooding are already at unprecedented levels. Finally, Canada’s real estate market is tied up in Real Estate Investment Trusts (a common investment for mutual funds), putting investors–and retirement savings–at risk.

Seeking higher ground

Building in Vancouver’s floodplains is just one example of how ongoing trends could add to future costs, both in Vancouver and beyond. Other climate hazards, such as wildfires and permafrost thaw, will also increase costs. Our latest report, Tip of the Iceberg, provides analysis of the known and unknown costs of climate change for Canada.

(1) A 100-year floodplain is riskier than it sounds: it means there is a 1-in-100 probability of a flood occurring in a given year. For example, a house in a 100-year floodplain with a 25-year mortgage has a 22 per cent chance of flooding at least once during those 25 years.