Last week, Environment and Climate Change Canada published their much anticipated update to Canada’s carbon pricing benchmark. The update is important. It sets expectations for how provincial and territorial programs covering fuels and large emitters must be designed after 2022 to meet federal minimum standards.

There’s a lot to like in this update from an effectiveness perspective. The update closes several loopholes that were eroding the price signal and strengthens long-term system integrity. Many of the updates explicitly address the risks to cost-effectiveness that the Institute identified in our Independent Review of Carbon Pricing Systems. They mirror our own recommendations for improved system design.

In some cases, however, the adjustments don’t go far enough.

Let’s unpack what the update does—and doesn’t—change for carbon pricing in Canada.

Improved effectiveness with expanded coverage and increased stringency

Here is what the new benchmark does:

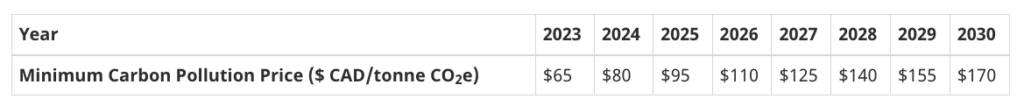

- It sets the minimum national carbon pollution price from 2023 to 2030. The carbon price will rise from $65/tonne in 2023 to $170/tonne in 2030. This is a good outcome since prior to the update, only Quebec had a long-term price signal to 2030 through its tightening emissions caps. This update sends a strong signal about future expectation for low carbon investments.

- It prohibits rebates or fuel tax decreases that are directly tied to fuel consumption. Provinces and territories must not implement measures that directly offset, reduce, or negate the price signal sent by the carbon price. Newfoundland, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island currently offer point-of-sale rebates limiting the overall increase of gasoline and diesel fuel price. The Northwest Territories and Nunavut are also offering point-of-sale rebates. Other provinces, notably Saskatchewan and Alberta, had mused publicly they would do the same. Banning this practice strengthens the effectiveness of carbon pricing within Canada.

- It prohibits free allocation to fuel distributors. This measure directed squarely Nova Scotia. The province was providing most allowances for free to fuel distributors to address income concerns for households. This practice seriously undermines the price signal. It lowers the cost of carbon that consumers pay—thereby weakening the incentive to reduce emissions. Other policy measures to address income concerns can be used that do not erode the long-term price signal, such as personal tax rebates or income tax reductions.

- It sets a minimum emissions coverage threshold for combustion sources. At a minimum, the carbon pollution price must apply to an equivalent percentage of greenhouse gas emissions from combustion sources as would be covered by the federal backstop system in the jurisdiction. Provinces and territories have the flexibility to tailor source coverage. This is a good step forward. As we noted in our Independent Review, a common standard of coverage would improve overall effectiveness. It would expand the coverage of the carbon price in some jurisdictions.

- It mandates coverage for industrial process emissions. The move to require process emissions to be included in large emitter programs expands coverage, thereby broadening the price signal. Our review found that the coverage of process emissions ranged between one per cent and 78 per cent. While these emissions will be covered, they will likely be freely allocated for the most part. At least for a while, as they are typically expensive to abate.

- It mandates more reporting. Provinces and territories will have to publish regular, transparent reports and/or information on the key features, outcomes, and impacts of their carbon pricing systems. This is a needed push to improve climate governance. Our Independent Review found that systems are often opaque, with key data needed to review system effectiveness absent. Notably, the Institute’s Independent Review found that data is typically not available to assess the functioning of large emitter programs and the trading markets they have created. This posed a large risk to overall long-term effectiveness since 40 per cent of Canada’s total emissions are covered by large emitter programs. Better data going forward will set the table for ongoing assessment and improvement in these policies over time.

Remaining long-term risks to Canada’s carbon pricing benchmark

Although a step in the right direction, the new benchmark does not entirely address some of the issues raised in our Independent Review. In particular:

- It doesn’t set minimum performance standards for industrial emitters. In Canada’s large emitter programs, competitiveness is protected by providing what is essentially free allocation to industry. Compliance payments or tonnes owed are set as a fraction of total facility emissions. This means that the average cost of the policy to the large emitter, or total compliance costs over total tonnes covered, is a fraction of the posted carbon price. The fraction of covered emissions subject to compliance is typically determined based on sector-specific performance standards. They are expressed in carbon intensity of production, which jurisdictions can define freely.

The Institute’s Independent Review determined that the average cost signal in Canada is exceptionally low for large emitter programs. It ranges from $1.80 to $25.60 per tonne, with an average price per tonne of $4.96. This represents a cost of 0.6 cents per dollar of GDP for industry, or 0.06 per cent of the economic value created by these sectors. With such low average prices, firms are unlikely to deploy the bulky investments in new technologies that Canada’s climate commitments require. Only British Columbia has a reasonably high average price, at $25.60 per tonne. The new benchmark continues to allow weak performance standards to exist, whereby the carbon price will continue to apply to a small fraction of the covered emissions. As the world prices more carbon, such weak standards are not necessarily in line with competitors carbon costs.

There is also a wide variation in average costs across sectors and jurisdictions. These differences have implications for both domestic competitiveness risks among jurisdictions and across sectors. The updated benchmark does little to address such uneven coverage, which we believe will lead to domestic competitiveness misalignments among jurisdictions under different carbon pricing programs. This is a matter of fairness. Canada as a federation must avoid a race to the bottom in average costs, with provinces lowering their average carbon price to compete with other provinces.

- It doesn’t mandate annual tightening rates for industrial performance standards. Surprisingly, the benchmark does suggest that provincial output-based pricing-type systems include mechanisms to support price predictability and market stability, including tightening rates on industrial performance standards. But the federal output-based pricing system itself does not currently define a “glide path” to better align and increase average costs of large emitters. This means that even though the marginal cost incentive will rise, the average cost incentive will remain weak, undermining the long-term price signal.

All in all, the new benchmark for carbon pricing in Canada is a welcome improvement. It sets new rules that all provinces and territories will need to follow. These updates enhance overall effectiveness, while still respecting provinces’ and territories’ design choices. However, more work will be needed to better align large-emitter programs across jurisdictions. It will also be needed increase overall stringency in line with our climate goals.