Last year, our family replaced our gas furnace with a cold climate heat pump here in Vancouver. The ability to cool our home during hot B.C. summers, cut our household emissions, and take advantage of government incentives ultimately pushed us over the edge. We initially weren’t sure if the switch would save us money, but I’ve now got a year’s worth of data to nerd out on and share.

The verdict? We saved about $200 on the total cost of heating and cooling our home for the first year. What’s more telling, however, is the role that government incentives played in making the math work on the up-front costs of making the switch. With most of these incentives now ending, how Canada will decarbonize its buildings sector is in serious doubt.

Our heat pump cut household energy use—and our utility bill

First, a few details about our situation. We replaced our 10-year old gas furnace that was reasonably efficient with one of the most efficient cold climate heat pumps on the market, which was also covered under federal and provincial rebates (more on this later).

The installation was done in mid-March 2024, which gives me a year’s worth of data to analyze. Here are the big takeaways on energy and cost.

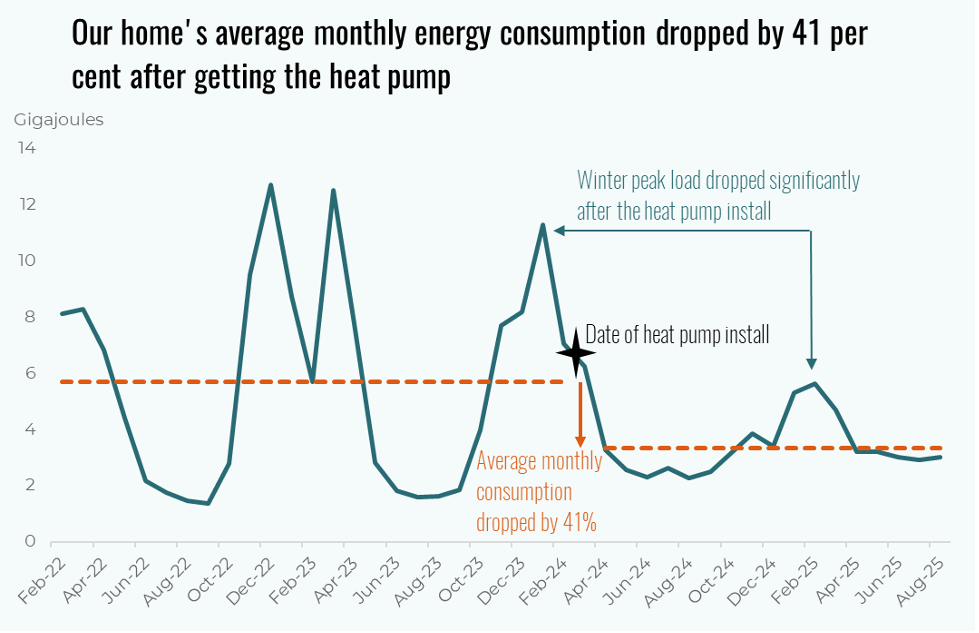

Comparing the year before and after the installation, the heat pump cut our total household energy use by 39 per cent. We knew that getting a cold climate heat pump would cut our energy consumption, but we were shocked by the immediate drop (see figure).

The heat pump has also been cheaper to operate. Overall, we saved about $200 in our total utility bills in the 12 months after the installation relative to our gas and electricity bills in the 12 months prior.

But the real kicker is that this drop in total energy use and cost happened during a year where our energy needs increased. We had a baby in December 2023 and did heaps more laundry during the full year with the heat pump (our dryer is the biggest draw on electricity in our house). This past winter was also colder, measured by the number of days with average temperatures below five degrees Celsius.

And, thanks to the new heat pump, we now have air conditioning in the summer that we never had before. Cooling has dramatically improved the comfort of our home on hot days and allows us to keep the windows closed when we get wildfire smoke. It also didn’t draw as much electricity as you might expect. As you can see in the figure below, the air conditioning barely shows up in our summertime energy use.

Government grants put the upfront cost of our heat pump on par with the gas equivalent

Finally, the policy details. The cost of retrofitting our house with a heat pump was big, particularly because we upgraded our electrical panel at the same time, which was about one-quarter of the total cost. We were able to qualify for both federal and provincial incentives, totaling $11,500. We also qualified for a no-interest loan through the federal government.

While every household’s situation will look different, these incentives are what ultimately made the math work for us. If you remove the electrical panel upgrade from the equation (something we needed to get done anyway), the grants put the net upfront cost of our heat pump roughly on par with the cost of installing a new high-efficiency gas furnace and air conditioner. And once you consider the modest savings we get on our monthly energy bills, our heat pump actually saves us money.

At the same time, the federal no-interest loan made the upfront cost manageable. Even after the grants, the cost of our heat pump would have been difficult to swallow all at once. The loan spreads out the cost over 10 years and is paid back in monthly installments, just like a mortgage.

Heat pumps are a cost-effective technology that can decarbonize households

Our one example provides a window into the broader challenges—and benefits—with reducing emissions in Canadian buildings. Analysis by the Institute shows that electrifying how we heat and cool our homes with heat pumps is the best and most efficient way to reduce building emissions. Following through on Canada’s climate commitments requires installing an additional 229,000 heat pumps between 2024 and 2026.

Yet recent reversals in climate policy will make this target difficult—if not impossible—to achieve. Federal grants under the Greener Homes Program ended earlier this year, and the no-interest loan program is abruptly ending October 1. At the provincial level, many granting programs have either stopped or scaled back. Eliminating the consumer price on carbon pollution removed one of the most cost-effective policies encouraging the switch to heat pumps.

With buildings generating 12 per cent of Canada’s total emissions, reducing emissions from this sector is paramount to achieve Canada’s climate goals. But it won’t come without new policies and incentives to fill the gap and help ensure cost-effective solutions are within most households’ reach.