This article was previously published in the Globe and Mail.

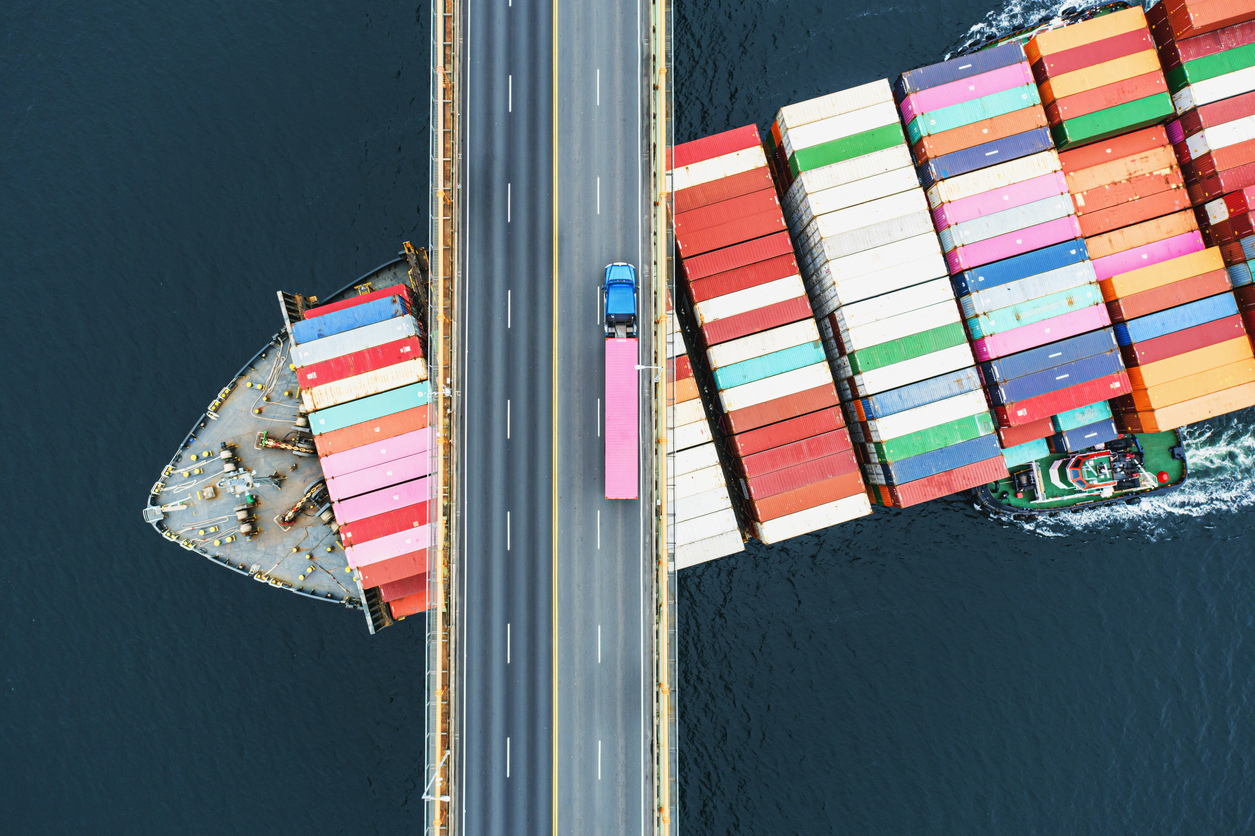

The race to attract global capital to finance Canada’s net zero transition is accelerating faster than anyone expected. To keep up with the global shift to clean energy sources change, Canada’s transition requires over $80 billion each year in new investments. Most of them need to come from the private sector. Yet financing this transition is now more challenging for Canada with the passage of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, which is poised to offer investors juicy returns south of the border.

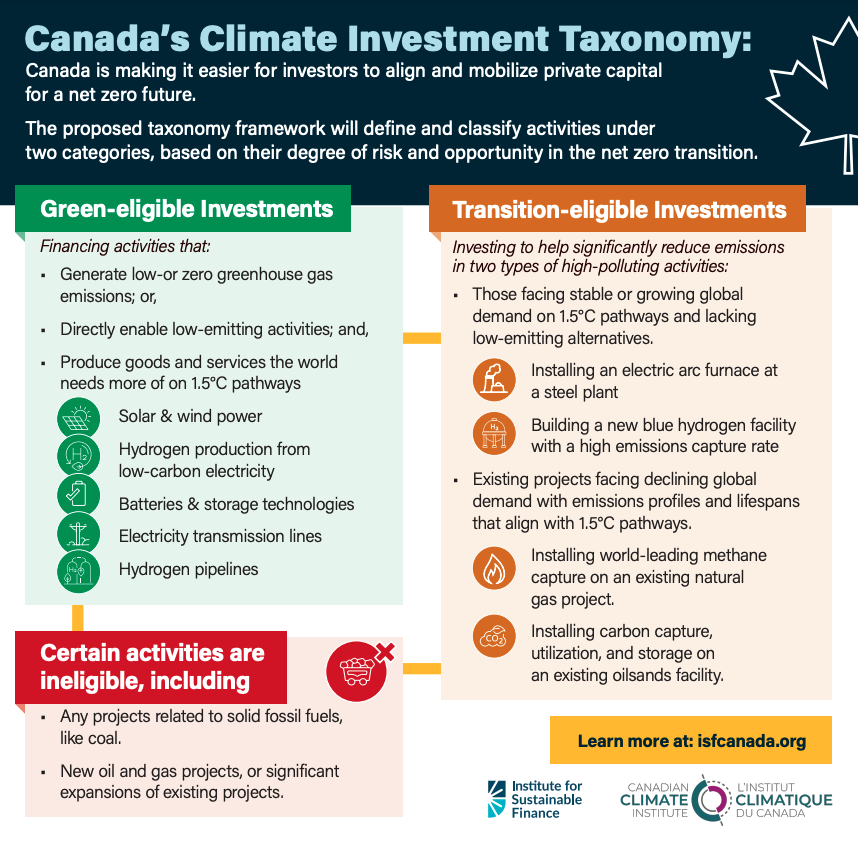

A newly announced climate investment taxonomy is a major step toward shoring up the country’s competitiveness. It has been developed and supported by the country’s 25 largest financial institutions through the federal Sustainable Finance Action Council (SFAC). The idea is to create standardized labels for what investments are—and are not—aligned with global climate objectives. The initial taxonomy framework, developed with research support from the Canadian Climate Institute and the Institute for Sustainable Finance, not only defines “green” investments but also the more controversial “transition” investments.

A taxonomy for Canada’s future prosperity

Successfully landing a climate investment taxonomy in Canada will be crucial to securing its energy transition and future prosperity. It will not only help mobilize private finance toward new, green growth. It will also help Canada decarbonize and transition its existing, emissions-intensive engines of growth. And if it’s done well, countries around the world, that will be watching closely, could adopt the Canadian framework.

But let’s take a step back: what even is a climate investment taxonomy? And how could having one help solve Canada’s competitiveness challenge in its energy transition?

A taxonomy for the energy transition

Climate taxonomies act like a gigantic sorting hat for the financial system. They offer a standardized and science-based way to determine whether specific projects align or don’t align with climate goals. In doing so, taxonomies can help clear up the avalanche of misinformation and greenwashing that currently plagues climate finance globally. At the same time, taxonomies ensure that investment dollars flow to the projects most urgently needed to drive the energy transition, such as renewables, batteries and storage, or clean hydrogen. Critically, taxonomies are an essential complement to other climate policies like regulations and carbon pricing.

Canada is among the last of the countries in the G7 and G20 to develop this type of taxonomy. However, it’s making up for lost time by providing a concrete framework to categorize “transition” activities: the parts of Canada’s emissions-intensive economy that can successfully be transitioned or transformed to align with a net zero future.

How to define the taxonomy

Defining this “transition” category is admittedly harder than identifying green investments. It requires a delicate balancing act, and has already attracted criticism. Yet the proposed taxonomy for Canada walks the line well.

Fundamentally, the taxonomy is designed to build and maintain the confidence of global capital markets. This is why the whole framework is grounded in climate science and the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5C degrees relative to pre-industrial levels. Anything less than this ambitious goal would undermine the taxonomy’s credibility.

Take, for example, how the framework treats oil and gas projects. It recognizes that reducing emissions from existing oil and gas production is crucial in the short-term, and transition-labelled investments could fund technologies that have value long into the future (for example, carbon sequestration infrastructure). New oil and gas projects, or expansions of existing projects, would be ineligible for taxonomy financing. And existing projects would only be eligible if the investment makes significant and transformational reductions in the emissions associated with producing oil and gas.

The framework could also unlock transition capital for other heavy-emitting sectors. Efforts to electrify Canada’s steel and auto manufacturing sectors, for example, could qualify for the transition label. As could other important transition projects, such as making low-carbon hydrogen from natural gas or low-carbon chemicals to fuel hard-to-decarbonize sectors.

Turning Canada’s taxonomy into a practical tool

Successfully defining energy transition activities in this way could have huge benefits for Canada’s entire economy. Decarbonizing Canada’s most energy-intensive and export-oriented sectors is fundamental to the country’s economic prosperity: they directly employ over 800,000 workers. The more these sectors can reduce emissions, the more competitive they will be in a global low-carbon economy.

Time is of the essence. Regulators and government, in collaboration with the financial sector, must move quickly to turn this framework into a practical, independent, and science-based tool to evaluate projects and portfolios. As the race for global capital accelerates, demonstrating credible and transition-aligned investment pathways in Canada has never been more important.