One could be forgiven for thinking that the world has stalled out on tackling climate change, given the rapid retreat from climate policy in the U.S., as well as the relatively subdued role climate issues played in the recent federal election.

However, recent developments show that quite the opposite is true: global climate policy and the energy transition continue to march forward, making recent setbacks in the U.S. outliers within a larger, long-term shift to clean energy.

The rest of the world is moving ahead on climate—that’s a big risk for Canada’s economy if the country doesn’t keep up

Take just one example: electric vehicles (EVs) are set to make up one in every four cars sold globally this year, according to the International Energy Agency. Last year in China—by far the world’s largest auto-market—EV sales made up roughly half of all new passenger vehicles sold. That share is expected to climb to 80 per cent by 2030. Globally, EVs are set to reach 40 per cent market share in just five short years, which will cut more than 5 million barrels of oil a day off of global demand.

That’s an important development for a country like Canada that currently depends on oil exports for a significant portion of its economic activity.

But this story isn’t limited to passenger vehicles. Many countries continue to expand their existing climate policies and these changes could have broad economic implications for Canada, especially at a time when the country is seeking to strengthen relationships with large non-U.S. export markets amidst trade uncertainty with the U.S.

For example, both China and India—the second and third largest global emitters—have recently signaled their commitment to cutting emissions. Chinese president Xi Jinping has stressed that shifting global realities will not slow China’s efforts to address climate change. In fact, China is expanding its carbon market—which is already the largest of its kind in the world—to include steel, cement and aluminum. This move will increase the scope of emissions covered by three billion metric tonnes, more than four times the size of Canada’s annual greenhouse gas inventory. India, for its part, is set to introduce a national carbon trading system next year.

In Europe, both the U.K. and the EU are broadening the scope of their emissions trading schemes by implementing carbon tariffs on imported goods. Once these policies are in effect (2026 in the EU and 2027 in the U.K.), countries exporting into Europe and the U.K. will pay a tariff unless they are already subject to carbon pricing in their home territory. Fortunately, for Canadian exporters, the country’s industrial carbon pricing system can help protect them from paying the full carbon tariff.

Climate policy in Europe more broadly continues to make progress. Early last year, the EU announced plans to strengthen their net zero legislation by setting a new target of reducing emissions by 90 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2040. And though insufficient support from governments has delayed the new target from coming into effect, things may speed up now that Germany, EU’s largest economy, has recently officially endorsed it.

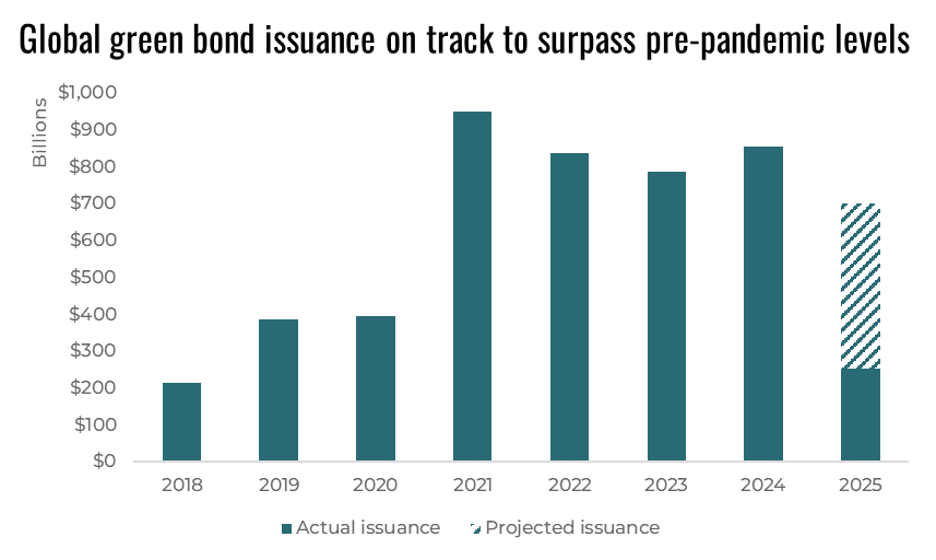

If all that wasn’t enough to demonstrate a clear global trend towards a low-carbon economy, consider investment trends. Within the last few years, investors have shown increasing interest in buying into the energy transition. More recently, the Trump government’s moves to undercut the greening of the financial sector as well as the EU’s attempts to streamline climate reporting requirements for companies have created uncertainty for investors. But the market for green bonds remains strong in countries like Australia, where the government is moving ahead with the release of its climate taxonomy, an important tool to support capital flowing towards low-carbon investments. Despite this year kicking off with Trump’s inauguration, one Australian investment firm reported that they issued more green bonds than regular bonds in the month of January. Globally, while issuance numbers are down slightly from the past four years, they remain on track to surpass pre-pandemic levels.

Canada needs to make climate a policy priority if it wants to stay competitive

Policy backsliding in the U.S. has enormous implications for Canada, particularly given our close trade ties.

However, the new federal government cannot be sidetracked by the setbacks south of the border given global momentum elsewhere.

If it wants to deliver on its promise of strengthening Canada’s economy, the new federal government needs to make climate a policy priority. The new federal government can start by strengthening industrial carbon pricing, finalizing methane regulations for oil and gas, finalizing the Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit, and releasing a made-in-Canada climate taxonomy.

Aligning Canada’s climate policies with those of the many countries that continue to make progress on climate will support Canada’s efforts to diversify its trade relationships, reduce internal trade barriers, and help the Canadian economy to remain competitive.