In August 2024, the remnants of Hurricane Debby brought record-breaking floods to Quebec, inundating 55 communities. Just a month before, nearly 10 centimetres of rain fell in Toronto in three hours, overwhelming the city’s infrastructure and flooding many homes and businesses. And in November 2021, an atmospheric river unleashed record-breaking rain in British Columbia, triggering landslides and floods that caused extensive damage, cutting off main access routes to several areas of the province, severely impairing the economy.

As climate change worsens, Canadians will experience a significant increase in the frequency and intensity of these kinds of flood events. Warmer air, caused by increasing concentrations of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, holds more moisture, leading to heavier rainfall and more intense storms. This, combined with melting snow packs, rising sea levels, and changing weather patterns, has created the conditions for more severe and unpredictable flooding. These floods are devastating for communities, economies, and livelihoods.

Climate change is driving increasingly severe and frequent floods

- Because of climate change, most regions in the country will experience increased rainfall, higher extreme rainfall, and increased severity in coastal storms (Zhang et al. 2019; Vasseur et al. 2017).

- Research shows that climate change intensifies many contributing factors that combine to elevate flood risk, including heavier rainfall and storm surges amplified by sea level rise (Denchak 2023; Greenan et al. 2019).

- Climate heating means that warmer air can hold more water than cooler air, increasing the risk of heavier and more extreme rainfall events. More rain is likely to fall in short, intense bursts rather than being spread out over a longer period (Westra et al. 2014).

- Increasingly frequent and severe short-duration rainfall events increase the likelihood of flash floods, especially in urban areas, by overwhelming storm sewers and drainage systems (Westra et al. 2014; Sandink 2015; Brown et al. 2021).

- Parts of southern British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces have seen an increase of two to three heavy rainfall days per year on average (Zhang et al. 2019; Vincent et al. 2018).

- Climate models project that by the end of the century, an extreme rainfall event that now occurs once every 20 years in Canada could happen every five years, and the amount of 24-hour extreme precipitation that occurs once in 20 years, on average, is projected to increase by 12 per cent (Zhang et al. 2019).

Floods can severely damage homes and infrastructure, costing billions of dollars

- Flooding is the most common and costly disaster in Canada. In the past decade, floods have averaged nearly $800 million in insured losses annually (Insurance Bureau of Canada 2024).

- Insurers estimate that for every dollar in insured losses from flooding, there are two dollars in uninsured damage that are borne directly by households and taxpayers (Honegger and Oehy 2016).

- Over 1.5 million homes across the country are located in areas of high flood risk (Ness and Florez Bossio 2024). Eighty per cent of Canadian cities are built, in whole or in part, on floodplains (Public Safety Canada 2022).

- As extreme rainfall and coastal flooding increase, the annual costs of flood damage to homes and buildings in Canada could grow three to five times by mid-century—amounting to over $5.5 billion—and reach as high as $13.6 billion by the end of the century (Ness et al. 2021).

- On July 16, 2024, in Toronto, nearly 10 centimetres of rain fell in three hours, leading to massive flooding across the city. Early estimates put the cost of this flooding at $1 billion in insurable losses, with the total costs likely several times higher (Pereira 2024).

- Canada has experienced five billion-dollar-plus flood events since 2011 (Insurance Bureau of Canada 2023; Manitoba Flood Review Task Force 2013; Insurance Bureau of Canada 2024; Public Safety Canada 2023).

- Many Canadian homeowners believe they have insurance that will pay for repairs and rebuilding after overland flooding, but only about 10 to 15 per cent of households are actually covered (Posadzki 2017).

- The households facing the highest flood risk in Canada either can’t get flood insurance or can’t afford it because the rates are so high (Public Safety Canada 2022).

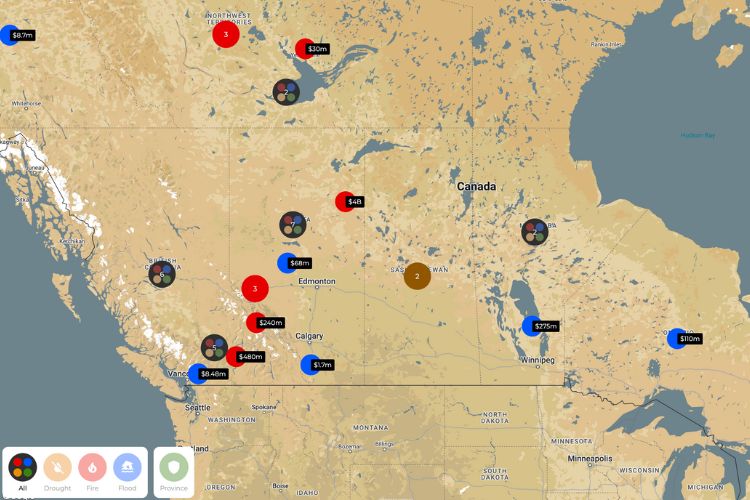

Explore the climate costs tracker to visualize climate-fuelled weather events in Canada.

More frequent and intense floods put people and communities at risk

- Heavy rainfall events can overwhelm small drinking water treatment systems, degrading water quality and increasing the risk of waterborne disease outbreaks (Wang et al. 2018).

- Over half of the waterborne disease outbreaks in the past 50 years in the United States occurred after episodes of extreme rainfall (Charron et al. 2011).

- Floods can be fatal, as people drown while wading or driving through flood waters or are trapped in flooded buildings (Government of Canada 2021).

- Injuries are common during and after floods due to swiftly moving heavy objects, damaged electrical wiring and appliances, and the risk of hypothermia from cold floodwater (Government of Canada 2021).

- The psychosocial impacts of flooding are significant, increasing family conflicts, financial stress, and feelings of isolation. In some cases, flooding can trigger or exacerbate mental health conditions such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (Glenn and Myre 2022).

- A few months after the Quebec floods of 2019, 44 per cent of those affected had moderate to high symptoms of post-traumatic stress, 21 per cent had symptoms of anxiety disorders, and 20 per cent had developed mood disorders (Institut national de santé publique du Québec 2024).

- Flooded buildings are quickly colonized by mold, fungi, and bacteria, which can cause or aggravate skin, allergy, eye, respiratory, and gastrointestinal problems such as asthma, conjunctivitis, and otitis (Institut national de santé publique du Québec 2024).

Governments can act to protect communities from worsening flood risk

- Flooding will only get worse as the concentration of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere continues to increase. Government action to manage this growing risk and limit further emissions is essential.

- Because the impacts of climate change on flooding are already here and getting worse from the emissions that have already occurred, communities and governments must work together to adapt and prepare for increased risk of floods today and into the future.

- Some of the key adaptation actions governments can take to reduce flood risk and protect communities include:

- Shifting development away from high-risk flood zones: To prevent placing more homes in harm’s way, provincial and municipal governments could restrict building in areas with high flood risk. In moderate-risk zones or areas prone to urban flooding, it’s essential to flood-proof new developments to minimize water damage (World Bank 2017).

- Enhancing flood protection infrastructure at the community level: Investing in new and improved flood protection infrastructure, such as levees, floodwalls, and nature-based solutions, can cost-effectively safeguard communities at risk of flooding (Ness et al. 2021).

- Support proactive relocation from high-risk areas: In a few areas where flood risk is too high to provide adequate protection, governments should engage with homeowners and communities to consider proactive relocation, offering appropriate assistance and incentives for moving to safer areas (Public Safety Canada 2022).

References and resources

- Three things governments need to do to protect homeowners and renters from the insurance industry’s perfect storm (Bourque 2022)

- Reporting Extreme Weather and Climate Change: A Guide for Journalists (Clark and Otto 2024)

- Under Water: The Costs of Climate Change for Canada’s Infrastructure (Ness et al. 2021)

Experts available for comment and background information on this topic:

- Ryan Ness is Director of Adaptation Research at the Canadian Climate Institute and the lead researcher on the Institute’s Costs of Climate Change series (Eastern Time, English and French).

- Sarah Miller is Research Lead in Adaptation at the Canadian Climate Institute (Pacific Time, English).

For more information or to interview an expert, please contact:

Claudine Brulé

Communications and Media Relations Specialist

cbrule@climateinstitute.ca

(514) 358-8525