The Four Siblings Prophecy

Shared by Elaine Alec

In the beginning, there were four siblings from each of the four races and they all lived on the same Land. In our Stories, we have always talked about the siblings and the four colours, like the medicine wheel: black, red, white, and yellow. When our Elders told these Stories, they did not reference the colours of the races in a derogatory way. They have shared these teachings for decades to talk about our relationships and to remind each other that we are all relatives.

Each sibling was given a gift that they were supposed to master. The Creator told the siblings, “You must go off and master these gifts, and when you come back together again, you will teach each other what you have mastered, and you will listen to each other and learn, and the world will be good. If you do not share your gifts, if you keep them to yourselves, or if you do not listen to each other, there will be war.”

The Creator gave each of the siblings a teaching. Some of our nations say the Creator gave each of the siblings a tablet with instructions and that those tablets are still out there. These tablets carry the original teachings that were meant to be shared between people so they could live in peace on Earth together. They were told that if even one of them forgot those teachings or cast their teachings to the side, that all humans would suffer, and the Earth would die. These teachings are said to be on tablets in Arizona, Tibet, Switzerland, and Mount Kenya.

The black sibling was given the gift of water. They were told that even in the desert, they would be able to find water and know how to harness its power. The yellow sibling was given the gift of air, that they would be able to harness its power for discipline and strength. The white sibling was given the gift of fire, that they would harness its power and use it to create engines and machines. The red sibling was given the gift of Land, that they would learn everything about the Land and its Natural Law and know everything about regenerating it.

The Creator told the four siblings that they would be sent into the four directions to master their gifts, and that what separated them would be what brought them back together again. So, the Creator struck the Land with a wooden stick and the Land began to crack and separate. And as the Land began to separate, what came up between them was water. It would be water that would bring them back together again.

Introduction

The global climate crisis is the most pressing challenge facing humanity. Activists, Knowledge Keepers, and scientists have been calling for urgent and concerted climate action at all levels (UNICEF n.d.; Onjisay Aki 2017; EEAS 2021). Yet colonial policy frameworks inhibit climate action through their entrenched patterns of inequality, exploitation, and environmental degradation (Deranger 2021), and are poorly equipped to truly address the challenges now facing society (Jackson and Victor 2019). The disconnect between Indigenous approaches to climate change—rooted in Sacred and Natural Law and Ceremony—and colonial policy frameworks—often siloed and surface-level—presents further challenges to developing effective climate policy. It is imperative that Indigenous Peoples and colonial governments work together to address this crisis and that Indigenous Peoples’ voices and perspectives guide climate policy processes. Climate change is not just an environmental issue, but an issue of human social, economic, and industrial organization at a global scale (Turner 2022; Kyle 2021); Indigenous Peoples know that all people are one with the Land, and that we must all therefore pursue climate policy methods and ways of being that facilitate holistic and interconnected approaches to the problem. As this case study will show, one way this must be done is through Ceremony.

Our case study responds to the question, How should First Nations’ Ceremony in so-called British Columbia (B.C.) influence climate policy? To search for answers, we reflect on our experiences and learnings from the Spiritual Knowledge Keepers’ Gathering on Climate Change (The Gathering) (Naqsmist and BCAFN 2024a). The Gathering was a two-and-a-half-day governance Ceremony hosted in November 2023 on Tsleil-Waututh Territory. It brought together 23 First Nations Knowledge Keepers from around B.C. to address the climate crisis, discuss its underlying causes and impact on the Land and all beings, and offer space to share Stories, songs, and healing. It kicked off the B.C. First Nations Climate Leadership Agenda process between the federal government and B.C. First Nations, coordinated by the B.C. Assembly of First Nations (BCAFN), and funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. The process seeks to set out a B.C. First Nations-specific policy agenda to guide changes to Canadian federal climate policy, programs, and funding through a memorandum to Cabinet. This memorandum will inform federal government budget decisions (BCAFN 2024)1.

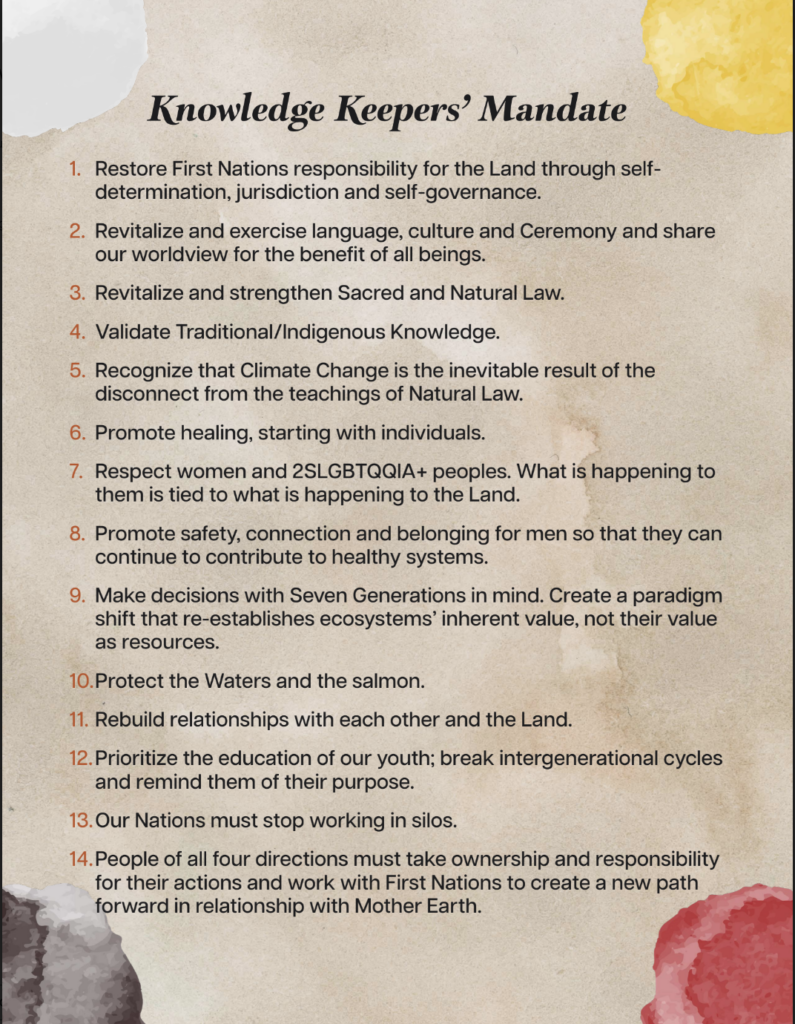

The Gathering was grounded in Sacred and Natural Law through the Circle process, which promotes that all voices speak (based on observations from Natural Law that each being is needed for the ecosystem to thrive)2. It was also grounded in prayer and acknowledgement of ancestors, animals, and all living beings, and songs, dances, and Stories that both represent and allow people to embody the natural world in governance. Naqsmist, an Indigenous consulting firm, captured notes and video to create a summary and develop a Mandate for moving the work forward. The event resulted in the Spiritual Knowledge Keepers Gathering on Climate Change report (Naqsmist and BCAFN 2024a) and Mandate (Figure 1):

The fourteenth Mandate item asks us to “create a new path forward in relationship with Mother Earth.” This is the fundamental challenge and where Ceremony can play a pivotal role. To better understand this dynamic, we consider below the legacy and limitations of colonial policies and the potential for their transformation using decolonial approaches rooted in Ceremony and Sacred and Natural Law.

What is ceremony, and why is it essential to climate policy?

“Ceremonies are intended to elicit the deepest response from yourself, from your soul and spirit. It is important in itself, significant; it can’t just be politics anymore. We’ve got to do something. We’ve got to stand up and be counted, be a voice.” — Hereditary Chief Dr. Robert Joseph (Naqsmist and BCAFN 2024a)

Indigenous Ceremony is fundamentally about connecting to the Land and all of Creation, and is itself a way of life. Ceremonies are often place-based, can take many forms, and are “a way of transferring knowledge, and remember[ing] the responsibility we have to our relationships with life” (Cajete 2000). They are also a protocol for belonging—to a family, to a people, to the Land, and to the Sacred, emphasizing interconnectedness, reciprocity, and respect through balance and renewal (Kimmerer 2013; Naqsmist and BCAFN 2024a; Cajete 2000).

Ceremony, in connection with Sacred and Natural Law, can be seen as both a policy in itself (i.e. parameters to guide future decisions), and as something broader (a way of being, a feeling, an ongoing process of discovery and action through relationships). In Ceremony, we arrive with respect and reverence for the Creator and we appeal to Natural and Sacred Law for permission and protection. Including Ceremony in policy helps to set the right relationship with one another and the Land. Ceremony reminds us to be humble and to hold responsibility rather than entitlement. Thus, it translates relational knowledge into parameters (principles, values, and intent) that guide decision making and resource allocation—or what the government of Canada calls policy (CHIN 2021).

Governance Ceremonies are a place where people gather and share Stories. As Indigenous Peoples, we use the information from those who have been on the Land to make decisions for how we will be on the Land for the next four seasons. By applying this understanding to climate policy, we arrive at a more holistic understanding that helps root decisions in larger systems thinking. Ceremony is a protocol and a practice for providing access to this way of thinking and being.

Tensions between ceremony and policy

“We had policy within our ceremonies. We had policies in our day to day life. They were brought out from watching our natural world and looking at creation. We had original instructions given to us. How do we follow those now? How do we maintain that in a colonial state? I think it’s really going back to listening to Land, listening to our youth. Listening to our Elders. Where are they trying to take us?” — Ginnifer Menominee (ICA 2023)

Indigenous Peoples have always known how to act in relationship to the Land. They recognize that the disconnect between people and the Land is the reason for the climate crisis. Policies are tools by which people operationalize values, and are thus a pathway for Indigenous worldviews to help address climate issues. But they are just that: tools. In the wrong hands, they can become weapons. So we must ask what values underlie their use.

Historical policies in Canada have been designed to assimilate and erase Indigenous Peoples. For example, some forms of policy undermined Indigenous Governance by targeting Ceremonial practice. Potlatches, which happen along the northwest coast, were banned by federal government policy from 1885 to 1950 (Section 3 of An Act Further to Amend The Indian Act, 1880, as cited in Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc., n.d.). This Act not only undermined Indigenous governance but also impeded cultural expression, demonstrating the power of policy as a tool of oppression (Monkman, Lenard. 2017).

Other policies moved Indigenous Peoples from their Lands onto reserves, which limited access to their Territories, eroding cultural practices and connection to place. In some cases, selection of reserve lands (often on lands deemed less valuable by settlers) resulted in maladaptation to climate change: homes relocated onto floodplains under the Indian Act are at increased risk of flooding, as seen most recently during B.C.’s atmospheric river of 2021 (Chakraborty et al. 2021; Alderhill Planning Inc. 2022; Yellow Old Woman-Munro et al. 2021).

Policies are tools by which people operationalize values, and are thus a pathway for Indigenous worldviews to help address climate issues.

While some governments and ministries are enhancing their approaches to establishing and managing relationships with Indigenous Peoples, Reed et al.’s (2021) analysis of Canadian climate plans shows that there is consistent failure to uphold Indigenous rights to self-determination; free, prior, and informed consent; or true Nation-to-Nation relationships. The B.C. First Nations Climate Leadership Agenda process is a case in point, although certainly not the only case: it allows for roughly two years of “meaningful engagement” with First Nations to inform a memorandum to federal Cabinet, which, once drafted, will likely undergo interdepartmental consultation (Government of Canada, 2020) before being presented to Cabinet for discussion and decision-making, a process that is shielded by confidentiality rules. Confidentiality supports the free expression of ministers, which promotes good governance (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2014), but it limits transparency in decisions that affect Indigenous Peoples. It also removes Indigenous rights and title holders from the decision-making table, degrading the collaborative intent of meaningful engagement and co-development. As a recent engagement participant shared, “Canada always falls short in its desire to be inclusive because of this Cabinet process. When Canada opens that door, it will be able to look at us as individuals and respect our rights” (Naqsmist and BCAFN 2024b).

This exclusion marginalizes Indigenous worldviews, governance, and rights recognition, protection and, implementation—which together contain answers to questions that much current climate policy seeks to grapple with. To move towards a policy approach that benefits rather than harms Indigenous Peoples, and that meaningfully addresses climate issues, Indigenous Climate Action concludes, “policy making must center our own worldviews and our own diverse approaches to governance [which are] based on relationship to the Land, ancestral knowledge and concern for future generations” (ICA 2022). To address the governance challenge presented above, one incremental way to centre Indigenous Knowledges, governance, and ways of being in climate policy would be to ensure that climate policy development and implementation are rooted in and guided by Ceremony.

A path through

“Ceremony focuses attention so that attention becomes intention. If you stand together and profess a thing before your community, it holds you accountable. Ceremonies transcend the boundaries of the individual and resonate beyond the human realm. These acts of reverence are powerfully pragmatic. These are ceremonies that magnify life.” — Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013)

The Knowledge Keepers at the Gathering emphasized that to address the climate crisis, we must uphold our responsibilities to each other and to Creation. Contextually appropriate Ceremony, conducted with proper protocols, provides access to a way of being that allows us to connect to all that is around us, and thus to better see, delegate, and uphold responsibilities.

The connective element of Ceremony reminds us of the nsyilxcen language (syilx okanagan), in which the word tmixʷ loosely translates to ‘all living things’, and the word tmxʷulaxʷ loosely translates to Land. According to Dr. Jeanette Armstrong, tmixʷ is literally translated as the life force, and tmxʷulaxʷ is the ‘life-force-place’. Humans are considered part of the life force “through Indigeneity as a social paradigm [that fosters] reciprocity in the regeneration of all life forms of a place” (Armstrong 2012).

For this reason, the governance Ceremony has a process orientation rather than one of results to ensure that people stay grounded in an embodied reverence for the Land and Creation. When individuals honour this way of life, their spirit and decisions are aligned with their purpose. Historically, as people contributed from their unique purpose, the group would work towards solutions only after all voices were heard.

Ceremony is an embodied connection to Indigenous identity—to individual and collective purpose in the life-force-place. Respecting Indigenous rights is respecting Ceremony because it promotes relationship with the Land and Creation. To do so properly, Indigenous and colonial institutions, governing bodies, and political, economic, and social structures and relationships need to be founded on Ceremony.

Knowing this, and returning to the first 13 lines of the Knowledge Keepers Mandate, each line is part of a bigger picture of climate solutions. Through Ceremony, the relationships between Mandate lines emerge as more important than any individual line. This is the case because, as elements of the life-force-place, we must all play our role as healthy contributors so that the entire system can be well. We are encouraged to transcend personal and structural barriers so we can grasp interconnectedness for the benefit of all beings.

Each community experiences different challenges on the Land and in their relationships. These challenges require tailored approaches to effectively address the complex relationship with Mother Earth. First Nations’ communities’ self-determining choices to act on—and governments’ support for—any of the Mandate lines constitute climate action, because impacts in one area reverberate to others. Patchwork approaches confined to colonial climate priorities do not meaningfully respect Indigenous rights. Ceremony reminds us why Indigenous-led approaches to climate action, rooted in Indigenous communities’ respective traditions and priorities and grounded in an underlying reverence for the Land, are needed.

While the way forward may not always feel clear, we know we cannot do this work without Ceremony. By connecting humans and the Land, Ceremony can be climate policies’ foundation, and all of our grounding.

A critical element of Ceremony is the way it centres and reinforces both reciprocity and responsibility. In Ceremony, we are reminded of our place in Creation: Sacred and Natural Law tell us how to be in the world and hold us responsible and accountable. While the way forward may not always feel clear, we know we cannot do this work without Ceremony. By connecting humans and the Land, Ceremony can be climate policies’ foundation, and all of our grounding.

The way forward

Ceremony is a necessary component of adapting to and mitigating the climate crisis because it is a way to see ourselves in the context of Sacred and Natural Law and a way to align our actions to Mother Earth’s needs. Policy development processes need to be guided by Ceremony and Indigenous Knowledges. Ceremony, as it relates to climate policy, helps shine a light on a proposed policy’s shortcomings. It helps us find words for the way that we feel when we come up against systemic failures. You cannot heal what you do not acknowledge, and Ceremony shows some of the ways in which Canadian climate policy falls short, as assessed through Indigenous worldviews.

Understanding this, effective climate policy development must be approached holistically, and through intentional grounding in place and Ceremony. Emerging from Naqsmist’s reflections on the Gathering, we offer the following recommendations for policy makers across cultures and within all orders of government:

- Climate policy efforts must be founded on continued implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

In particular, the following articles apply to our recommendations: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 43, 44, and 45. Broadly, the UNDRIP Annex must guide implementation of these articles to ensure that the approach to respecting Indigenous rights is appropriate (United Nations, 2007).

- Federal and provincial governments must support and provide targeted resource capacity for First Nations to conduct Ceremony in culturally appropriate and self-determining ways.

First Nations and other Indigenous groups should continue to practice and promote Ceremony as a way of relationship building, both with others and with the Land. Furthermore, Ceremony must be an integral and consistent component of any co-development or engagement process between Canadian governments and First Nations. All involved in the policy making process should be active participants or observers of Ceremony, where appropriate. This must include funding Knowledge Keepers to attend policy-development processes, recognizing their Land-based and spiritual experiences as knowledge, and supporting communities to continue to foster coming-of-age ceremonies and practices, thereby creating new generations of Knowledge Keepers to maintain and strengthen humans’ connection to the Land. Care should be taken to avoid misrepresenting, pan-indigenizing, or diluting Ceremonial processes. Ceremony must not be tokenized and must be seen and implemented as an ongoing responsibility to follow Natural and Sacred Laws and protocols.

- Federal and provincial governments must allow First Nations to set the table for Indigenous/non-Indigenous climate policy and law development.

Letting First Nations set the table means ensuring equitable and enhanced rights-based participation that cultivates safer spaces for discussion led by First Nations teachers, guides, and spiritual leaders (Shallard and Wale 2023). Indigenous Peoples must exercise their right to free, prior, and informed consent when policies impact their rights to their lands, territories, and resources. Culturally and contextually-relevant Ceremony must be practiced in these settings from the outset. This could be supported by adding and sharing reflective components within policy development processes to ensure transparency around how Indigenous Knowledges have been valued and upheld, how they need to be further included, and whether and to what extent they are being considered in decision making. Furthermore, many First Nations and Indigenous groups have pre-existing national Laws (both Sacred and Natural Law and in some cases written traditions or other forms of law) that apply to climate initiatives. These laws must be upheld in collaborative governance processes between Indigenous groups and Canadian governments. While there are significant systemic barriers to true Nation-to-Nation climate policy development processes, including the federal Cabinet process, Ceremony opens space for Indigenous worldviews to frame and lead the discussions and provides opportunity for cross-cultural learning, promoting a heart and Land-centred approach that can support incremental changes over time.

- Over time, federal and provincial governments must commit to a paradigm shift in climate policy-making to centre the well-being of the Land by respecting and incorporating Ceremony and Sacred and Natural Law into decision-making and implementation approaches.

In other words, and in alignment with the fourteenth Mandate item, we must work together to forge a new relationship with Mother Earth. A paradigm shift is necessary to transition away from decisions and policy that centre people and profit at the expense of the Land, climate, and Sacred and Natural law. This shift is needed both in many colonial and Indigenous spaces—Ceremony helps all of us come together and live our lives in a good way. Ministries with conflicting mandates should be brought together to engage with Indigenous Peoples in good faith around issues of the natural world—which, as we have learned in this work, touch all ministries, since we humans are part of the natural world. Engaging in Ceremony is an act of good faith, and as Ceremony is included in more and more co-governance initiatives between Indigenous Peoples and Canadian governments, our hope is that small changes at the level of the individual stemming from participation in Ceremony can lead to larger systemic changes that benefit all humans and the Land. Additionally, funds for research initiatives on collaborations across Indigenous communities, academia, and governments could allow for a better understanding of how Ceremony and policy can work together to not only promote First Nations climate leadership but also to promote this paradigm shift. Slowly, we hope, the expansion of Ceremony in governance spaces will reduce the burden that Indigenous Peoples face by participating in siloed engagements that do not align with their worldviews and that lack transparency and accountability, and will promote improved relationships within and between First Nations, other Indigenous communities, and Canadian governments.

Conclusion

Through the practice of Ceremony, we remember who we are.

We believe that if we follow the right protocols and practice Ceremony—even if it is not always clear how to do so or what the result will be—the necessary components to reform colonial climate policy and to begin to respond appropriately to the climate crisis will continue to emerge. This will happen because over time, through the practice of Ceremony, we remember who we are, and our actions will reflect this deeper understanding.

Ultimately, the value of Ceremony does not come from thoughts or through logical analysis. It comes from experiences of connection that spur action. As Kukpi7 Fred Robbins said, “We must know our Territory—where the sun goes up and down, how the wind blows in the morning and evening. There is no ownership of the Land, only a sense of belonging” (Naqsmist and BCAFNa 2024). This feeling of belonging is what the Knowledge Keepers are challenging us to understand. Like in the Four Siblings Prophecy, this is the gift they are sharing. Will it bring us together again?

Footnotes

- Note: we recognize that diverse Indigenous Peoples have different Ceremonial and governance practices. Furthermore, while the Gathering and the B.C. First Nations Climate Leadership Agenda process are distinctions-based and First Nations-specific, we use both the terms First Nations and Indigenous in this work depending on what was quoted or the context of the words’ use.

- According to John Borrows, Sacred Law stems “from the Creator, creation stories or revered ancient teachings that have withstood the test of time” (2010), while “Natural Law is based on observations of the physical world…and attempts to develop rules for regulation and conflict resolution from a study of the world’s behaviour” (2010).