INDIGENOUS SEED KEEPING: A CULTURAL FOOD AND CLIMATE ADAPTATION PRACTICE

While agriculture is not part of all Indigenous communities’ food systems and practices, many communities’ ancestral food systems include seed keeping and crop cultivation practices. For some Indigenous communities, seed keeping and agriculture was not historically part of their food systems, but has since become so, in some cases due to Indigenous mobility and displacement across regions, climate change altering territories’ growing parameters, and cross-community knowledge sharing. Although the practice of saving and adapting seeds is not exclusive to Indigenous Peoples, they conduct these practices in ways that are culturally distinct, informed by intergenerational belonging to place, and involve Indigenous science, economics, spirituality, gender, environmental stewardship, and community laws and governance.

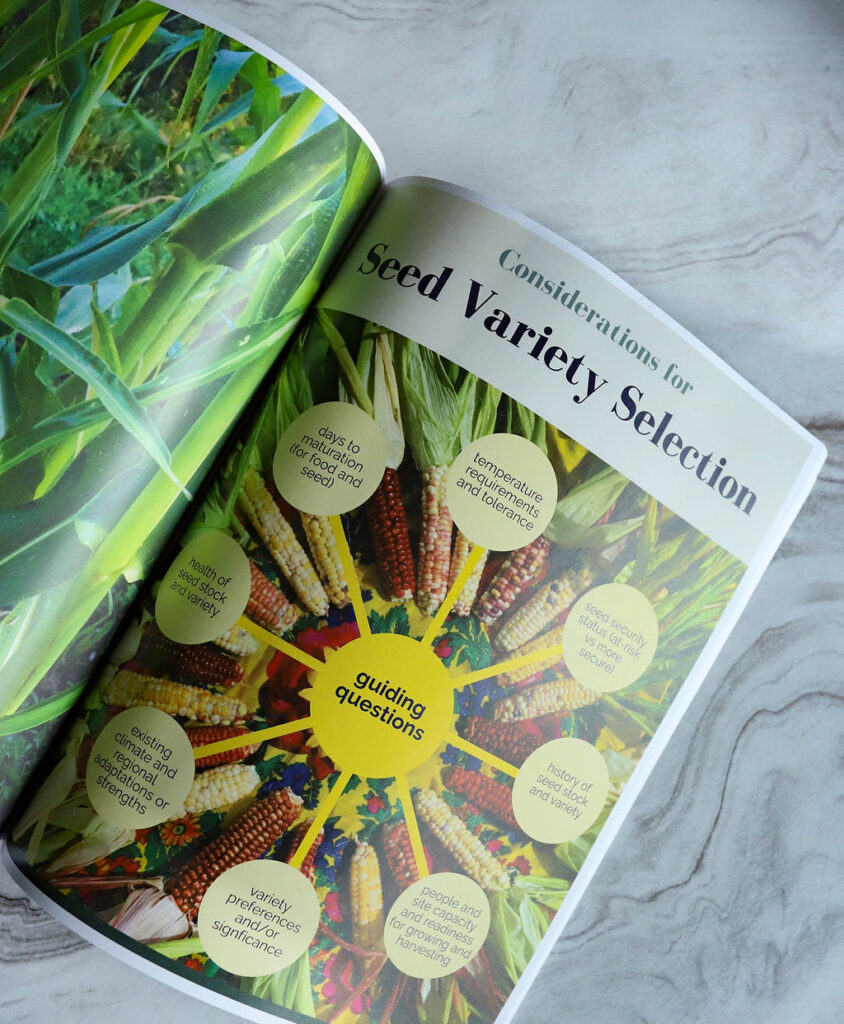

For generations, Indigenous seed keepers have been seed keeping to develop, maintain, or restore ancestral and culturally significant seed varieties and to adapt existing and newer varieties to respond to regional growing conditions. Indigenous seed practices are guided by ethics of responsibilities and form a culturally specific role often referred to as Indigenous seed keeping or being an Indigenous seed keeper. Indigenous seed keepers steward food crops that have significance to communities’ diets and that support spiritual or cultural practices. These relationships with select seed varieties carry cultural significance, with many communities having stories, songs, dances, games, ceremonies, specific language, food processing technologies, and/or recipes connected to particular crops and varieties. Historically and currently, some communities specialize in particular crops and varieties, trading these with other communities in reciprocal economic alliances for other foods. Seeds have travelled and continue to move across territories through trade routes and exchange networks, resulting in the seed and food biodiversity we see today. Indigenous seed keepers have always adapted and selected seed varieties for new climates and growing conditions, and varieties that thrive in a given territory over time become significant to a family’s or community’s diet and food culture. Through adaptation-oriented decision-making, seed varieties become more equipped to growing conditions influenced by climate change, resulting in more resilient seeds and more successful harvests.

Indigenous seed keeping and agricultural food sovereignty are compromised by both climate change and colonialism. Indigenous seed keepers are having to preserve at-risk cultural seed varieties for cultural survival while also adapting these varieties to be responsive to changing climate factors for current and future food provision .Climate change factors are altering growing conditions and seasons and are destabilizing cultural knowledge about planting cycles, and in consequence, Indigenous seed keepers are struggling with crop yields and seed losses. Indigenous people growing for food production are similarly impacted, with culturally significant seed variety food crops struggling under increasingly unpredictable environmental variables, impacting communities’ health, food access, food security, and food cultures.

Indigenous seed keeping and agricultural food sovereignty are compromised by both climate change and colonialism.

Compounding these climate pressures are the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization Indigenous food cultures and practices. Land dispossession and displacement, federal regulation of identity, the assimilatory imposition of European and industrial agriculture, forced starvation, and the restriction of Indigenous access to capital and equity are all detrimental influences on the health of Indigenous food sovereignty (Carter 2019; Robin et al. 2020). Colonization also continues to obstruct Indigenous seed keepers’ self-determined access to healthy land, preventing seed keepers from conducting agricultural food practices and cultural seed adaptation. Additional facets of colonialism dissect Indigenous Peoples from their relationships with their cultural foods and food knowledge systems, such as the legislation and criminalization of food practices, seed biopiracy and knowledge appropriation, and child apprehension and family rupture through residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, incarceration, and the current child welfare system, among others (Robin et al. 2021; Simpson 2004). Indigenous seed varieties were historically appropriated by museums, private collectors, and companies, and many of these seeds are still in institutional archives and non-Indigenous corporate inventories. Seeds are often retained or sold without the consent of the communities who developed them. While Indigenous seed keepers continue to steward these varieties, low stocks and obstacles to growing have impacted varieties’ genetic health and stability. Cumulatively, these factors have led to the loss of seed varieties and interruptions to knowledge transmission within and across generations.

As stewards of food cultures and climate adaptation, Indigenous seed keepers and growers are a frontline of self-determination through their resistance to and insistence on self-determination from colonialism and biodiversity loss. While there is an information gap on crop biodiversity in Canada, in the past century, there has been a 75 per cent global loss in food crop biodiversity, and today, only 9 to 12 crops comprise 75 per cent of today’s global crop-based food intake (FAO 2004; FAO 1997; Khoury et al. 2021). This trend is concerning as seed biodiversity is significant both culturally and from a dietary perspective to Indigenous people and global populations, and it is also critical to growers to provide greater food security and food system resilience. Genetic and trait diversity across seed varieties also allows for greater regional and genetic solutions for seed keepers to choose from to adapt climate vulnerable food crops.

METHODOLOGY

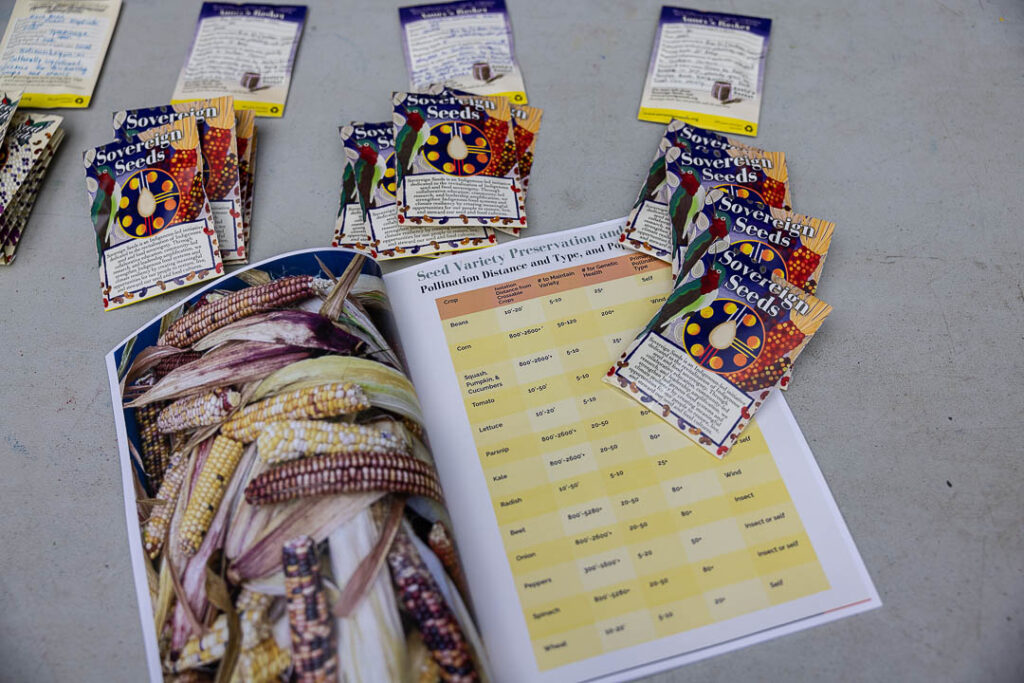

Sovereign Seeds, a national Indigenous by-and-for seed and agricultural food sovereignty organization, has been working to advance Indigenous-led seed efforts by revitalizing seed keeping knowledges and supporting the adaptation of cultural crops to respond to climate change. Insights generated from Sovereign Seeds’ activities were gathered over three years and were anonymized and analyzed for recurring themes and trends.

These insights were documented with contributors’ consent through a variety of virtual and in-person climate adaptation-oriented activities including collaborative community programming, collective visioning sessions, and partnership communications. This analysis included 16 insight events, as well as email and call correspondence, with 52 contributors in total. Insight event contributors comprised Indigenous individuals, families, grassroots initiatives, organizations, and businesses, with the majority of individuals and groups operating in not-for-profit capacities. A majority of insight contributions occurred between 2022 and 2023; however, some insights gathered in 2021 were provided retrospective consent for inclusion in the analysis. Contributors’ ancestral territory affiliations varied significantly, particularly in cases of urban-situated groups and in multi-group and multi-community events and conversations. Localities spanned British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. Insights were gathered and analyzed using Indigenous research methodologies and frameworks. This case study is one of several organizational actions of relational accountability as an applied Indigenous research methodology in response to community-expressed demands for multi-sector support for Indigenous agricultural food sovereignty and seed adaptation climate action. These learnings offer insights into the intersections of Indigenous food sovereignty and Indigenous climate adaptation that are intimately known and lived by Indigenous people but are often overlooked by non-Indigenous actors and by those operating with influence over levers of power.

With limited public literature on these topics, it is important to acknowledge language use and the case study limitations (see Glossary and Notes on Case Study Language). Not all Indigenous perspectives and experiences are represented here. Indigenous for-profit activities are underrepresented relative to not-for-profit activities, and important realities of gender, sexuality, and multiracial identity are not addressed.

Seeds of wild-harvested or foraged foods native to communities’ ecosystems are also culturally significant food species, but this case study is limited to cultivated food varieties within garden and farming contexts. Further, land dispossession and displacement is the dominant barrier to Indigenous seed adaptation and climate action, but adequately addressing this barrier was beyond the limitations of this case study. Similarly, concerns and recommendations towards international governance mechanisms were voiced in insight events but are also not presented in this case study for brevity. Insight events highlighted some Indigenous priorities and generated calls to action in agricultural food and seed sovereignty that are not included here due to being specific to inter- and/or intra-Indigenous conversations. Lastly, this case study does not present a comprehensive treatise of the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization and the dominant globalized industrial agricultural food system on Indigenous Peoples’ food sovereignty and climate adaptation efforts.

KEY LEARNINGS AND THEMATIC FINDINGS

Findings gathered through Sovereign Seeds’ insight events highlighted barriers and needs in cultural food crop climate adaptation specific to communities’ and regions’ historical, environmental, geographical, and political contexts. Assessed together, common themes related to Indigenous seed and agricultural food sovereignty and adaptation emerged, including knowledge revitalization and transmission, resourcing seed sovereignty and seed climate adaptation efforts, and governance and leadership.

Knowledge revitalization and transmission and seed variety adaptation efforts

Indigenous-led knowledge revitalization is urgently needed to start, strengthen, and continue seed climate adaptation response action. Due to colonial interruptions to seed knowledge transmission, there are not many people within families and community networks with the cultural knowledge and memory of seed keeping who carry multi-decade experience, or what many refer to as seed Knowledge Holders or seed Elders. This relatively small number of experienced seed Knowledge Holders are the primary practitioners of seed climate adaptation and are encouraging newer seed keepers to take climate action. New and emerging seed keepers, who comprise a majority, are keen to revitalize these cultural climate adaptation practices, but identify that seed adaptation is a knowledge and skill set ahead of their current knowledge set.

All seed learners and leaders identified that a strong foundation in culturally rooted knowledge in gardening and seed keeping is a prerequisite to being able to adapt food crop varieties to changing climate conditions. Both emerging and experienced seed keepers expressed a need for improved access to Indigenous-only culturally relevant seed learning opportunities for newer seed keepers to gain the foundational knowledge and applied experience needed to undertake seed adaptation. New and emerging seed keepers named time, capacity, and lack of financial support for learning as barriers. Experienced seed keepers expressed personal capacity concerns, citing financial stressors and lack of resources to fund their and their helpers’ time as barriers to teaching. Many seed Knowledge Holders, also noted negative experiences with non-Indigenous institutional, governmental, non-profit, and small-scale sustainable agriculture actors that resulted in having their knowledge and ideas appropriated, their labour under-compensated, and/or their invited involvement tokenized.

Seed keepers articulated that colonialism has and is impacting Indigenous seeds and knowledge transmission, and that climate change, which is already threatening seed and food cultural crops, is also impacting knowledge transmission, a key activity needed to take climate adaptation action. Between the reality that many experienced Indigenous seed keepers are aging, and the multiple structural and climate-associated challenges that both younger and older experienced Indigenous seed keepers face in learning and teaching, knowledge transmission is a significant and pressing requirement for Indigenous seed climate adaptation.

Seed keepers articulated that colonialism has and is impacting Indigenous seeds and knowledge transmission, and that climate change, which is already threatening seed and food cultural crops, is also impacting knowledge transmission, a key activity needed to take climate adaptation action.

Seed adaptation is multi-year climate action. In this long-term commitment, Indigenous seed keepers face financial precarity arising from the challenges of securing and maintaining infrastructure, labour, equipment, and sustained and self-determined access to land. This precarity undermines the long-term strategic planning and action required to adapt seed varieties for climate. Seed Elders and Knowledge Holders identified the responsibility they carry in both ensuring the survival of culturally significant at-risk seed varieties in their community networks while also teaching others cultural seed keeping and climate adaptation practices. Under these pressures, compounded by a lack of resources, there is little opportunity for experienced seed keepers to scale back their efforts, tend to their wellness, or innovate, let alone navigate a challenging growing season and low seed yield. These combined pressures means newer seed keepers have few learning opportunities and little room for error learning with at-risk cultural seeds while older seed keepers don’t have the time, capacity, or resources for succession of seed inventory and transition of responsibility to others.

Recognizing and resourcing knowledge transmission and adaptation efforts

Insight event contributors—both for-profit and non-profit— overwhelmingly named granting and lending relevance and access across government and philanthropic resources pathways as significant obstacles to seed keeping and variety adaptation.

Contributors expressed frustrations with granting and lending actors not recognizing the complexity of Indigenous cultural agricultural food revitalization and food adaptation, which are not simply practices of food production and distribution or climate monitoring. Contributors noted that across all sectors, funders and lenders did not understand or value the relevance of seeds and seed keeping to culture, education, food security, health, and climate action. For those engaged in non-profit activities, this issue was particularly challenging as they felt funders thought seed-focused projects were irrelevant to granting priorities. Those engaged in for-profit activities experienced a lack of recognition and understanding of the specific barriers and needs they have to start, maintain, or grow for-profit activities due to historical and ongoing Indigenous-context specific barriers they face. Contributors voiced concern that funds often go to initiatives and entities whose activities fit the restrictive criteria and siloed solutions of non-Indigenous funders and lenders.

Those engaged in non-profit seed and agricultural food revitalization and climate adaptation activities emphasized funding approach and delivery as barriers. Non-profit contributors noted that funders prefer new projects and ideas over existing activities and that they predominantly provide short-term and non-renewable funding commitments, an approach that is not appropriate for Indigenous seed keeping projects, which often require multi-year support commitments. Contributors also reported experiences of funders prioritizing investments in Indigenous entities that are high-profile, well-funded, and well-staffed with substantial governance infrastructure, entities that have non-Indigenous partnerships, and entities that promote reconciliation narratives and do not openly express critical viewpoints. These contributors also named the lack of available unrestricted funding opportunities as a challenge. Contributors articulated a need for more self-determination in expenses, greater application and reporting accessibility, greater timeline flexibility, less prescriptive evaluations, culturally appropriate and accessible language, and reduced application and reporting demands.

Indigenous people engaged in both non-profit and for-profit activities strongly expressed a need for funders and lenders to shift away from prescriptive and paternalistic funding models.

Some Indigenous cultural food organizations and businesses are not directly involved in but support and engage with Indigenous seed adaptation initiatives through the use or purchase of their produce and seed harvests. These contributors named conflicts with grantors and lenders on product or service sourcing: many contributors value sourcing from Indigenous producers, while granting or lending partners prioritize profit. Environmentally sustainable and/or climate-responsive Indigenous for-profit food initiatives noted a conflict between their priority to support cultural values of social and environmental seed and food production responsibility with the economic priority of grantors and lenders, who devalue or discredit cultural ethics. These businesses felt overlooked for enterprises that are more in line with western capitalist markets, such as industrial agriculture activities and agriculture initiatives without cultural or social reciprocity-oriented objectives.

Indigenous people engaged in both non-profit and for-profit activities strongly expressed a need for funders and lenders to shift away from prescriptive and paternalistic funding models. Contributors across both activity types identified issues with eligibility requirements, and noted that purchase of land, equipment, and infrastructure should be supported expenses. Recipient eligibility was also a concern. The eligibility criteria in many non-profit government and philanthropic sector funding opportunities disqualified a number of contributors from accessing resources, and for contributors’ for-profit endeavors, small-scale activities were often disqualified based on insufficient capital contribution and perceived insufficient income-generating and scaling potential.

Seed governance, leadership amplification, and understanding and accessing policy-making

While some initiatives are resourced through provincial and federal programs, the Indigenous food sovereignty movement and Indigenous seed variety adaptation efforts are overwhelmingly occurring outside of Canadian government policy and program development. Insight event contributors largely prioritized Indigenous sovereignty and governance and expressed a degree of mistrust of and/or frustration with all orders of Canadian government. The majority of seed keepers noted limitations of government recognition and policy change and that government processes are designed to be inaccessible to grassroots actors. Contributors also felt that while change will not be primarily achieved through policy engagement, national and provincial policies are impacting their seeds, food systems, climate action, cultures, and territories. Many felt strongly that Indigenous people should be meaningfully engaged as sovereign nations and leaders instead of as stakeholders or special interest groups, and that current engagement and translation of government policies, plans, and programs is inadequate. Some barriers identified include exclusionary engagement pathways, inaccessible policies and programs, culturally inappropriate interactions and solutions, and perpetuation of colonization through government regulation of identity, food systems, and territories. There were also challenges of erasure of on-the-ground growers’ voices through preferential engagement with government-recognized Indigenous representative bodies.

Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy (NAS), released in 2023, is the first strategy for climate adaptation objectives, and was accompanied by the re-release of the Government of Canada’s Adaptation Action Plan, which outlines federal financial commitments to climate adaptation amongst provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments (Government of Canada 2023a; 2024). The degree of meaningful and adequate engagement with Indigenous people in the strategy and action plan was questionable. Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) held a National Adaptation Strategy Visioning Forum in 2021 to develop the NAS; of the over 60 participants engaged in the Forum, only two National Indigenous Organizations (NIO) were involved but were not identified, and no other Indigenous participation was named (Government of Canada 2023b). Absent from the NAS is mention of the importance of food crop seed biodiversity and seed adaptation in climate resilience, seed adaptation as a climate action, Indigenous crop adaptation leadership, cultural agricultural food production and factors impacting these activities, and the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and cultural agriculture overall. Similarly, Canada’s 2020 National Biodiversity Strategy (NBS) presents sustainable agriculture as a solution to reduce the impacts of industrial agriculture on biodiversity, yet it only briefly addresses the role of seeds and only in the context of native non-cultivated plants such as trees, with no mention of food crop seed adaptation (Government of Canada 2024a). Further, while it engaged federally-recognized Indigenous governing bodies, the NBS engaged no Indigenous seed or agricultural food sovereignty groups in its engagement sessions (Government of Canada 2024a).

Federal programs funding climate change adaptation efforts fail to adequately recognize and resource Indigenous seed variety adaptation. The First Nation Adapt Program, a Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada climate response program, was developed to support First Nations communities and organizations south of the 60th parallel to assess climate change impacts and develop and take climate response action (Government of Canada 2023c). While not restricted to these action areas, the program has focused largely on climate-related natural disaster mitigation and response, as directed by the again unidentified First Nations groups that ECCC and Natural Resources Canada engaged in the development of the program. Among the 40 projects funded in the 2022-2023 cycle, none were dedicated to food adaptation (Government of Canada 2023d). Similarly, Indigenous Services Canada’s now closed Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program funded a number of meaningful community agricultural food projects through a Food Security stream, yet seed adaptation and adapting crops for climate change were not identified activities in any of the funded projects (Government of Canada 2023e; Climate Telling 2021).

The erasure of Indigenous food climate adaptation leadership from government climate conversations also extends to federal responses to agricultural challenges and solutions.

The SAS discussion document names climate adaptation and resilience as one of five priority issue areas, and specifically, recognizes regionally specific applied climate adaptation research programs as a crucial solution. The SAS 2023 “What We Heard” report highlights barriers and priorities that seed keepers have also named in our insight events, yet the SAS consultation process did not engage an adequate breadth of Indigenous sustainable agriculture experiences and leadership. The report disproportionately represents Indigenous for-profit food producers’ perspectives, and SAS document language overall emphasizes market production activities and examines adaptation for the purpose of increasing commercial yields and commercial product quality. This market based perspective neglects the many cultural value based perspectives Indigenous seed and agricultural actors have on applied Indigenous economics. As a result, Indigenous not-for-profit initiatives and activities, which comprise a majority of Indigenous seed climate adaptation leadership and cultural food knowledge, are largely underrepresented and undervalued in the SAS.

The erasure of Indigenous food climate adaptation leadership from government climate conversations also extends to federal responses to agricultural challenges and solutions.

The absence of Indigenous cultural crop climate adaptation across national action plans and programming reveals government funding priorities and definitions of climate adaptation activities, and it also reflects what contributors strongly voiced in Sovereign Seeds’ insight events, including issues of engagement and consultation, funding priorities, and funding access in areas of climate, culture, and agriculture. Many contributors felt government responses favoured for-profit market participation and sector-based food production as solutions to Indigenous food insecurity and climate adaptation. Contributors described this as culturally inappropriate and assimilationist and an approach that is deepening economic pressures, pitting culture against survival, and creating divisions amongst Indigenous people in the food sovereignty movement. While contributors largely agreed that support is needed for Indigenous for-profit cultural agriculture producers and agrifood market participants that operate sustainably and with accountability to cultural values, many expressed that government responses and policy priorities are neglecting the contributions and perspectives of Indigenous food leaders who are protecting crop biodiversity and leading sustainable agricultural climate adaptation outside of for-profit food production.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Create transparency and accountability of processes and support and increase Indigenous leadership engagement and amplification

The imposition of Canadian state federalism onto Indigenous governance has resulted in preferential engagement with government-favoured Indigenous representative bodies that do not represent seed keepers and cultural growers. Further, bureaucratic accountability has shifted between provincial and federal jurisdictions in ways that do not support Indigenous territorial and traditional governance and nation-to-nation negotiations. Indigenous food sovereignty and seed governance, and the cultural and place-based laws that inform this governance, are sovereign and legitimate, independent of recognition by Canadian and international governments and law. Within western governance frameworks, Indigenous seed keeping and seed climate response exists within and at junctions of climate strategy, intellectual property, biodiversity, cultural rights, and Indigenous rights. Nation-to-nation engagement in Indigenous agriculture and climate adaptation requires increased access to decision making tables, a demystification of mechanisms and decision processes, and more time for preparation and participation. While not a substitute for community-based, community-specific grassroots leadership and Indigenous governance that exists independent of colonial government recognition, Indigenous-led models can generate policies and programs that are better accountable and responsive to community priorities. Our analysis identified recommendations and pathways to improved participation for and amplification of on-the-ground community groups in areas of food sovereignty, agriculture and agri-foods, cultural revitalization, and climate action:

- Deploy an Indigenous-led collaborative model to support decision making transparency, access, and appropriate process timelines. This model would see Indigenous-dedicated Indigenous liaisons across all relevant departments and advisory bodies tasked with providing transparency and translation of processes, documents, and decisions to cultural agriculture leaders and practitioners. The objective of such a model is not to assimilate Indigenous negotiation and decision-making processes within non-Indigenous rights-based governing bodies via Indigenous employment, but rather to better facilitate and operationalize nation-to-nation governance.

- Support on-the-ground Indigenous food and food climate adaptation leadership through multi-year commitments for and the formation of independently organized Indigenous -led and -comprised coalitions. Improved leadership amplification through these measures would help to address the intersecting issues of food sovereignty, agriculture and agri-foods, cultural revitalization, land remediation, and climate action. To ensure accountability and representation, such bodies must be organized by, governed by, and representative of for-profit and not-for-profit regional food producers, growers, and Knowledge Holders independent of (though potentially supported by) band council and government-funded service agency leadership. These collective organizing bodies can act as liaisons with relevant government departments to advance policy change, providing member-responsive programs, and would be accountable to their members’ priorities.

- Operate Indigenous hiring streams within tiers of Canadian government for the development and deployment of Indigenous-led consultations, programs, policy, and strategies with nation-to-nation partnership principles. Give priority accountability to community coalitions’ and on-the-ground leaders’ priorities, timelines, and protocols of conducting governance.

- Improve Indigenous engagement and consultation in government strategies and program development to ensure balanced representation of for-profit and non-profit activities, improved grassroots participation, and more accessible engagement timelines and communications to facilitate their participation. In the case of the SAS for instance, subsequent revisions and associated programs must better recognize Indigenous seed keeping as a uniquely impactful and active climate adaptation action and more strongly engage Indigenous seed keepers and non-profit Indigenous food sovereignty practitioners as key actors in sustainable agriculture and climate response.

- Provide stronger support for the creation of Indigenous-authored content, including policy analyses and research that is developed by Indigenous seed and food sovereignty-dedicated individuals and initiatives operating independently of federally favoured Indigenous representative agencies. Funding support and access to policy power is needed for new and existing Indigenous food sovereignty and Indigenous food climate adaptation research and education centres, programs, community groups in order to generate community-accountable and responsive collaborative contributions.

- Extend greater authority and legitimacy to Indigenous contributions in cultural and creative forms that do not reflect western research and research. Indigenous publications need to be weighed as meaningful contributions to policy and program development across government and philanthropy.

Increase opportunities for and improve processes of low-barrier, multi-year, and self-determined resource distribution for non-profit and for-profit entities

Multi-year commitments create greater space for food relationships and systems to be repaired and help shift initiatives from survival-based operations to long-term success and sustainability, while also making space for exploration and innovation, which is in alignment with Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing. Non-Indigenous for-profit and not-for-profit organizations and businesses should consider multi-year and low-barrier contribution policies of directing resources to Indigenous cultural agriculture seed and food initiatives through unrestricted donations and/or multi-year and low-barrier grants opportunities. This funding must be flexible and Indigenous-led or -guided, Indigenous-staffed, accessible, and culturally relevant, with advisory council, board, and/or staff representation of on-the-ground cultural food and climate response experience. Our analysis identified key needs and recommendations to promote these improvements:

- Increase low-barrier and Indigenous-led or Indigenous-guided funding funding support from government and non-government granting foundations for Indigenous-led not-for-profit groups addressing agricultural climate adaptation, seed efforts, and cultural agriculture knowledge transmission. This applies to all funding actors, particularly from large, greater-resourced sources such as granting foundations and multi-year governmental funding programs.

- Increase Indigenous-led or Indigenous-guided flexible funding commitments from values-aligned partners with significantly lower administrative requirements for local scale non-profit efforts, such as seed libraries/banks, community gardens, and cultural food sovereignty learning programs.

- Improve low-barrier investments from Indigenous and non-Indigenous governing bodies and granting agencies for both for-profit and non-profit Indigenous seed keeping and cultural food production initiatives and leadership.

- Provide greater support from all levels of government, local leadership, granting entities, and investment and lending institutions to Indigenous for-profit seed and food initiatives, such as for market gardeners, cultural food producers, and agritourism businesses, and small-scale and family entrepreneurs and enterprises.

- Ensure low-barrier Indigenous-led access to capital and granting from for-profit Indigenous initiatives conducting seed adaptation, and for-profit Indigenous initiatives that provide support to these initiatives, that champions activities and business models that reflect Indigenous economies and ethics.

- Ensure resourcing of cultural agriculture climate adaptation efforts is culturally relevant from development through to delivery. Responsive and effective resourcing includes ensuring Indigenous individuals, families, entities, and formal and informal groups doing the on-the-ground work define and assess success and shape funding processes in food system revitalization and climate adaptation.

- Improve the factors and educate the actors that are influencing the issue of qualified donee status and granting eligibility for non-profit initiatives. Significant change is needed to combat the power disparities and exploitation Indigenous initiatives face as grassroots initiatives operating both independently of and on shared platforms and in intermediary relationships, to dismantle barriers Indigenous initiatives face in accessing resources and expanding administrative capacity.

- Ensure multi-year granting and lending commitments for all Indigenous seed and agricultural food adaptation initiatives, both for-profit and non-profit. Project efficacy is depedent on multi-year planning and action.

- Improve access to unrestricted funding in granting and lending commitments for all Indigenous seed and agricultural food adaptation initiatives, both for-profit and non-profit. Eligible expense criteria need to support Indigenous self-determination by allowing unrestricted funding for self-identified priorities, such as equipment and infrastructure, operations and administration, staff and organizational development, and land access, return, and acquisition.

Recognize seed keeping and food culture and spirituality in food adaptation policy and resourcing

To reduce fundraising burdens on Indigenous initiatives to defend community-informed and culturally appropriate solutions, granting entities need strong operationalized awareness of the role of holistic approaches in Indigenous food adaptation solutions and of the historical and ongoing harms to Indigenous food systems. Our analysis identified recommendations to advance community-responsive and culturally appropriate policy and granting and lending programs:

- Improve anti-oppressive training and education for all actors across government and philanthropic sectors on Indigenous food sovereignty history, politics, perspectives, and ethics. Training that emphasizes non-Indigenous actors learning to practice Indigenous cultural food practices, rather than these learning priorities, fails to address power imbalances inherent in funding relationships, risks replicating histories of cultural knowledge extraction, and does not create systemic and structural awareness needed to create tangible sector change.

- Government and non-government entities must recognize Indigenous seed keeping as a climate adaptation practice. These entities must also recognize associated practices such as healing, food culture, and language learning activities as relevant priorities that are indivisible from seed keeping and climate response action. Spiritual, cultural, and technical knowledge revitalization and knowledge transmission activities are necessary for Indigenous-led food system climate adaptation.

- Extend recognition beyond optics and apply labour justice across government and non-government strategies and programs to see ethical compensation for seed learning and teaching labour and investment in seed adaptation efforts. For Indigenous food systems to thrive, Indigenous food leaders and learners must be provided conditions to thrive.

CONCLUSION

Indigenous seed keeping and Indigenous food sovereignty is subjected to the pressures of survival under an imposed capitalist economic system, the globalized industrial food system, climate change, and colonially constructed food insecurity. As an act of agency and self-determination under these oppressions, Indigenous seed climate adaptation action also exists at the intersections of knowledge revitalization movements, decolonial governance, anti-capitalist community organizing, and entrepreneurship and reimagined cultural economies. While these intersections engender political and cultural tensions across Indigenous seed keepers and the government, philanthropic, and corporate sector powers that impede their efforts, Indigenous seed adaptation learners and leaders continue to apply responsive climate solutions. Learners and leaders do this through the extensive land-based knowledge and community collaboration that has seen Indigenous food systems persist through both colonization and climate change. Pressures to have Indigenous knowledge and strategies fit western philanthropic and government models are not only hindering Indigenous food and climate leadership but are assimilatory and counterproductive to seed biodiversity, agricultural climate monitoring, and adaptation. The Indigenous food climate adaptation movement needs to be recognized as critical climate action and Indigenous seed and food growers need to be engaged as frontline climate responders. For just and effective Indigenous food climate adaptation, government and non-profit actors must better defer to Indigenous definitions of success and Indigenous-led holistic assessments of the activities and resources they need to take action. Indigenous governance and self-determination must lead the development and delivery of funding and investment programs and the development of strategic action plans and policies impacting Indigenous people in climate change and agriculture. Thematic insights revealed in this case study analysis emphasize the interconnectivity of Indigenous sovereignty, seed and food biodiversity, and climate resilience, and the deep need for restitution of leadership and resources towards a just and climate-resilient food sovereignty future.

Indigenous seed keeping and Indigenous food sovereignty is subjected to the pressures of survival under an imposed capitalist economic system, the globalized industrial food system, climate change, and colonially constructed food insecurity.

GLOSSARY AND NOTES ON CASE STUDY LANGUAGE (click to expand)

Indigenous views on the case study topics and associated definitions vary. These terms and definitions are not reflective of all Indigenous perspectives.

Agriculture: Agriculture and farming are alienating terms for many Indigenous peoples in Canada due to their association with colonial efforts to assimilate Indigenous people via western agriculture and its contemporary relationship with industrial farming (NWAC 2021). Forced assimilation and oppression through settler farming methods spanned residential schools, church-run farm settlements, experimental research farms and forced labour farms, and pass and permit policies, among others. Some preferred terms include food sovereignty, growing, and gardening. The term agriculture in other contexts extends to includes livestock, livestock feed, aquaculture, and other food production activities, agriculture and cultural agriculture are used interchangeably in this case study to speak specifically to plant crops grown for food with cultural teachings and methods.

Canada: The use of the term Canada does not reflect many contributors’ perspectives on the politics of acknowledgement of the Canadian state, with many preferring to use so-called Canada, what is colonially known as Canada, and within the colonial borders of Canada as an acknowledgement of settler-colonial occupation and Indigenous displacement and as a linguistic assertion of Indigenous sovereignty.

Communities: Use of the terms communities and community partners refers to and is inclusive of Indigenous on- and off-reserve urban and rural communities, organizations, grassroots initiatives, and informal groups.

Culturally significant seed varieties: In this case study, culturally significant seed varieties and seeds refers to cultivated food crop varieties that Indigenous peoples historically and/or presently have relationships with as part of their cultural food systems. This largely involves seed varieties that were developed by Indigenous ancestors hundreds of years ago and might or might not persevere today, but this term can also include other seed varieties that families and communities have recently developed or adopted into their food systems and have created cultural meaning with in recent decades.

Indigenous: Indigenous in this case study refers to people Indigenous to what is known in the English language as North America.

REFERENCES (click to expand)

Carter, Sarah. 2019. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (2nd ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Climate Telling. 2021. Food Security. http://www.climatetelling.info/food-security.html

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 1997. The State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). https://www.fao.org/3/w7324e/w7324e.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2004. What is Happening to Agrobiodiversity? Building on Gender, Agrobiodiversity and Local Knowledge. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). https://www.fao.org/3/y5609e/y5609e02.htm

Government of Canada. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2022. Government launches consultations for a Sustainable Agriculture Strategy. https://www.canada.ca/en/agriculture-agri food/news/2022/12/government-launches-consultations-for-a-sustainable-agriculture-strategy.html

Government of Canada. Environment and Natural Resources. 2023a. Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-

plan/national-adaptation-strategy/intersol-report.html

Government of Canada. Environment and Natural Resources. 2023b. Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy: Vision Forum. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/national-adaptation-strategy/intersol-report.html

Government of Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. 2023c. First Nation Adapt Program. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1481305681144/1594738692193

Government of Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. 2023d. First Nation Adapt Program: funded projects in 2022-2023. https://www.rcaanccirnac.gc.ca/eng/1698771955468/1698771985864

Government of Canada. Indigenous Services Canada. 2023e. Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1536238477403/1536780059794

Government of Canada. Environment and Natural Resources. 2024. Government of Canada Adaptation

Action Plan. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/national-adaptation-strategy/action-plan.html

Government of Canada. Environment and Natural Resources. 2024a. Canada’s 2030 National

Biodiversity Strategy. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/biodiversity/national-biodiversity-strategy/milestone-document.html

Hart, Michael. 2007. “Cree Ways of Helping: An Indigenist Research Project”. Doctoral dissertation, University of Manitoba.

Khoury, Colin K., Stephen Brush, Denise E. Costich, Helen Anne Curry, Stef de Haan, Johannes M. Engels, Luigi Guarino, et al. 2021. “Crop Genetic Erosion: Understanding and Responding to Loss of Crop Diversity.” New Phytologist, 233(1) (October 20, 2021): 84–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17733.

Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC). 2021. The Agrodiversity Pilot Project: Report on Findings Related to Best Practices & Investment Opportunities for Indigenous Women. https://nwac.ca/assets-documents/AGRI-REPORT-2-final-2-2.pdf

National Farmers Union. 2023. AAFC’s Sustainable Agriculture Strategy: Eight things you should know.

https://www.nfu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/SAS-8-things-you-need-to-know.pdf

Robin (Martens), T. R., Mary K. Dennis, M. K., and Michael A. Hart. (2020). “Feeding Indigenous People in Canada”. International Social Work, 65(4): 652–662.

Robin, Tabitha., Kristin Burnett, Barbara Parker, and Kelly Skinner. (2021). “Safe Food, Dangerous Lands Traditional Foods and Indigenous Peoples in Canada”. Frontiers in Communication, 6.

Simpson, Leanne. 2004. “Anticolonial Strategies for the Recovery and Maintenance of Indigenous Knowledge”. American Indian Quarterly, 28(3): 373–384.