Barriers to innovation in the Canadian electricity sector and available policy responses

Enabling broader decarbonization through Energy Systems Integration

“Our people have borne witness to climate change through deep time”

This essay was commissioned to inform the research and recommendations in our report Sink or Swim: Transforming Canada’s economy for a global low-carbon future, as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

In a time of unprecedented crises—including climate change, economic impact, loss of biodiversity, and a global pandemic—we recognize the importance of leadership and collective action to address these crises locally and globally. This essay shares Indigenous insights, concerns, and recommendations to guide the transition to a low-carbon economy. Specifically, it supports establishing Indigenous protected and conserved areas, expanding guardian programs, and building the conservation economy.

Historical and cultural context

Fourteen-thousand-year-old carbon-dated charcoal from a Heiltsuk village campfire located on what is now referred to as Triquet Island in unceded Heiltsuk territory off the Pacific Northwest coast confirms that our people were living on this land many thousands of years before the Roman Empire or the Egyptian pyramids. Our presence was known when the Earth was covered by ice and before the western red cedar migrated up the coast and the salmon populated our rivers, back to a time when sabre-toothed tigers and giant sloths roamed the Pacific Northwest. Our people have borne witness to climate change through deep time. According to this archeological carbon dating, during the first 7,000 years of this vast timescale, our people were harpooning sea mammals, while in the last 7,000 years we were eating more fish, such as salmon and herring.

Our Heiltsuk language also validates this ancient relationship to place. The name of a local marine passage referred to on navigational charts as Nulu Passage originates from the word Nula and in our Heiltsuk language means “eldest sibling.” Nulu Passage is in close proximity to the ancient Heiltsuk village site on Triquet Island. Our language and names also connect us to specific places in our territory and to each other. For example, I have two Heiltsuk names that I received in potlatch ceremonies. The name I carried as a youth, and now share with my grandson, is Athalis, which means “far up in the woods” to commemorate the eight months I spent alone on an island in observance of Heiltsuk ǧvi̓ḷás (laws). It is also the name of a Big House. My Hereditary Chief’s name, λáλíya̓ sila, which means “preparing for the largest potlatch,” was inherited from my late uncle, Robert Hall. λáλíya̓ sila was the first human ancestor who came down at Roscoe Inlet at Clatsja, where he landed on a salmon weir as a half man, half eagle.

Meaningful community engagement is the bedrock of the climate action work currently underway in Heiltsuk homelands. The Heiltsuk have a long history of working together to govern and manage our ecosystem for abundance. For at least 14,000 years, ǧvi̓ḷás (laws) have determined relationships internally, externally, and with the land, waterways, and the spiritual world. Based on principles of respect and balance, this system cultivated abundance through constant change. The last Ice Age and melt were survived by the Heiltsuk because of our strong systems of relationships and values. These same values continue to infuse the work of the Heiltsuk community towards climate action and justice. The latest community engagement of more than three hundred Heiltsuk citizens, held in 2021, demonstrated low conflict and high agreement around transitioning to clean energy. This supportive environment enables the Heiltsuk Climate Action Team to act decisively and coordinate local action on the climate crisis.

Meaningful community engagement is the bedrock of the climate action work currently underway in Heiltsuk homelands.

Heiltsuk Nation’s relationship with nature and the seven fundamental truths

Our Heiltsuk ancestors practised controlled burning of forests, transplanted salmon from salmon-bearing streams to those that did not have salmon, and built clam gardens and fishing weirs to develop a sustainable fishery. This stewardship ethic goes back into deep time when raven transplanted herring from Gildith to Nulu. Throughout our long history of continuous occupation of our territory, our people developed laws and systems of governance that have sustained us through many difficult times. We have been on a journey through time and place that’s depicted in the Heiltsuk’s Sacred Journey initiative, which shares the story of Tribal Canoe Journeys through Indigenous place-based people’s stories, practices, and values—an important example of human resiliency.

In 2009, I served as an Indigenous advisor to Biodiversity BC leading up to the 2010 International Year of Biodiversity. We organized and compiled a report with Heiltsuk, Haida, and ‘Namgis knowledge keepers called Staying the Course, Staying Alive–Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability. In this report, we delineated core values, or fundamental truths, that all three coastal native nations subscribe to. These core values are validated through stories, practice, language, and maps. The following seven truths affirm ancient relationships to place and current concepts of biodiversity, stewardship, and sustainability, and provide an important balance for scientific knowledge:

Truth 1: Creation

We, the coastal First Peoples, have been in our respective territories (homelands) since the beginning of time.

Truth 2: Connection to Nature

We are all one. Our lives are interconnected.

Truth 3: Respect

All life has equal value. We acknowledge and respect that all plants and animals have a life force.

Truth 4: Knowledge

Our traditional knowledge of sustainable resource use and management is reflected in our intimate relationship with nature, its predictable seasonal cycles, and indicators of renewal of life and subsistence.

Truth 5: Stewardship

We are stewards of the land and sea from which we live, knowing that our health as a people and our society are intricately tied to the health of the land and waters.

Truth 6: Sharing

We have a responsibility to share and support, to provide strength, and to make others stronger in order for our world to survive.

Truth 7: Adapting to Change

Environmental, demographic, socio-political, and cultural changes have occurred since the Creator placed us in our homelands, and we have continuously adapted to and survived these changes.

The responsibility to care for lands and waters

These fundamental truths have given rise to powerful solutions for addressing climate change and sustaining biodiversity. As Indigenous place-based peoples, we have a sacred responsibility to look after the lands and waters and resources. To achieve our vision of sustainability requires a convergence of local and traditional knowledge, ancestral laws, and the best of what western science has to offer.

For too long, the dominant approach to natural resources has been one of exploitation and exhaustion. But we are connected to the resources that give us life. If we burn through them, we undermine our own futures. Yet if we relate to the natural world in a more thoughtful way, the herring, kelp, salmon, caribou, and moose will remain—not just for us but for generations to come.

To achieve our vision of sustainability requires a convergence of local and traditional knowledge, ancestral laws, and the best of what western science has to offer.

And if we continue relying on carbon-intensive systems, we will not only worsen climate change, but we will endanger the natural systems that sustain us. We have seen the dangerous consequences of these systems firsthand.

On October 13, 2016, for instance, an articulated tug and barge ran aground in Heiltsuk territory. The tug sank and spilled more than 100,000 litres of diesel fuel and 3,700 litres of lube oil, hydraulic oil, gear oil, and spent lubricants into our pristine waters. The vessel operator, who had fallen asleep at the wheel, pleaded guilty, was fined, and funds were set aside to do impact mitigation work. The Heiltsuk currently have a civil suit pending against Canada.

This incident severely impacted our whole community. It was as if a close relative had died. We had to take responsibility for our place through acting as first responders, documenting the first 48 hours, and completing an adjudication report. In the aftermath of the disaster, we plan to establish a Heiltsuk emergency response team and a first responders centre in the central coast of British Columbia. We will also continue expanding the work that maintains healthy lands and waters. This stewardship builds stronger communities and low-carbon prosperity.

Opportunities for Indigenous leadership to improve approaches to development in the Pacific Northwest and boreal region

We have lived in our coastal homeland in relationship with natural resources for millennia. But in recent years, we have seen a sharp decline in ocean resources such as salmon, herring, and Dungeness crabs. Overfishing has taken a toll and so has climate change, creating effects such as big blobs (warm water patches) and higher ocean carbon levels making the water more acidic and altering its chemistry, leading to thinner shells, stunted growth, and premature death in Dungeness crabs.

Heiltsuk Guardian Watchmen track these changes and draw from the expertise of knowledge keepers that has developed over generations. Their research is shaping the Heiltsuk Nation’s decisions about how many crabs can be taken from the water and which areas must be protected to help them recover.

The same pattern is unfolding across the country. There are over 70 Indigenous Guardians programs operating in Canada. Guardians are the eyes and the ears out on the land and the water, and they are helping their Nations respond to climate change. They monitor shifts in the timing of when migratory birds arrive, where caribou find food in winter, when rivers melt in spring, how salmon populations are faring, how drought impacts red cedar, and why wildfires are growing more intense.

Indigenous Guardians are playing a vital role in creating and managing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) across Canada. These areas are critical to Canada’s ability to meet its international climate change and biodiversity commitments, now and in the future.

Indigenous-led conservation is proven to generate sustainable prosperity. Guardians programs offer well-paying jobs that create outsized benefits in small communities—each job supporting family members and purchases in the local economy. IPCAs and Guardians programs also generate new business opportunities and spur investment in regional economies.

Local and traditional knowledge teaches us about long-standing natural systems and processes that have been similar for generations. Climate change disrupts these patterns with erratic shifts in snowpack, ocean chemistry, and timing of seasons.

Indigenous-led conservation is proven to generate sustainable prosperity.

A premise of western research is to establish a baseline. In some cases, western science has between 20 and 80 years worth of data for Northern landscapes. But local Indigenous knowledge is thousands of years old. It is imperative that these two knowledge systems work together to address the climate crisis.

Guardians programs reflect this powerful combination. They join place-based expertise with western tools for measuring water temperature, salinity, permafrost, and other data.

Governments have a role in limiting risks and expanding Indigenous-led opportunities

In many locations, Guardians are the only ones on the land tracking climate change. Crown governments simply don’t have the financial resources to put field stations in remote areas to do this work across the North, but Guardians are already on the ground working in traditional territories. Partnering with Indigenous nations is a fiscally sound approach to helping mitigate climate impacts.

We need the Guardians’ knowledge to inform climate-related policies and decisions, whether it’s setting limits on Dungeness crab harvests or reducing development in carbon-rich lands. Several Indigenous nations, for instance, have proposed creating Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the Boreal Forest. The boreal is the largest remaining intact forest left on the planet, and in Canada alone, it holds about 12 percent of the world’s land-based carbon reserves. Indigenous Protected and Conservated Areas ensure large boreal lands remain undisturbed and prevent enormous amounts of carbon from being released into the atmosphere

Taken together, current proposals would permanently protect well over 20 billion tonnes of carbon—equivalent to almost 100 years of Canada’s annual industrial greenhouse gas emissions.

The work of Guardians benefits not only Indigenous communities, but all of humanity. Guardians draw on thousands of years of relationship with the land to ensure resources that we all depend on—from crab to caribou, clean waters to carbon storehouses—are sustained into the future. As the climate crisis intensifies, it’s time for Canada to support this work. Providing long-term investment in Guardians programs will help Canada honour its climate and conservation commitments and help all of us navigate our changing world.

Opportunities and recommendations

Indigenous communities are inextricable from the environments they are in relationship with, creating a powerful community responsibility to the land, water, and air. It is time Crown governments tapped into the wisdom of this powerful community responsibility through meaningful community-level engagement with Indigenous communities on the climate crisis. The engagement must be solution-focused, community-driven, and well-funded. Indigenous communities must be a driving force behind climate action, not simply have a seat at the table.

It is time Crown governments tapped into this wisdom through meaningful community-level engagement with Indigenous communities on the climate crisis.

The following four areas provide opportunities for collective action:

- Supporting Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship, including Indigenous Guardians. This should be a core part of Canada’s efforts to meet its new commitments to protect 25 per cent of lands and waters by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030, and should be incorporated in Canada’s post-pandemic economic recovery plan.

- Promoting economic reconciliation, community resilience and prosperity. This includes reimagining what prosperity looks like, addressing economic inequality, and developing new business models that will also help Canada transition to a low-carbon economy.

- Pioneering innovative financing mechanisms and untapped sources to ensure ample resources are available for land and resource management, biodiversity conservation, prosperity, climate resilience, and transition to a low-carbon economy.

- Working with governments to recognize nature-based solutions such as the boreal forest’s ability to capture and store carbon. This includes finding effective ways to create and monetize carbon offsets to provide communities with innovative revenue options for conserving lands and helping Canada meet its biodiversity and climate goals.

Canada is already taking steps towards supporting these efforts, both through the Canada Nature Fund and the National Indigenous Guardians pilot project. These renewed efforts will help us move forward together to create resilient and healthy economies at the local, regional, and national levels, while also helping Canada transition into a low-carbon economy.

Frank Brown is Hereditary Chief and a member of the Heiltsuk Nation from Bella Bella. He is currently an Adjunct Professor at Simon Fraser University, Resource and Environmental Management Department and recently received an Honorary Doctorate of Law from Vancouver Island University.

Indigenous partnerships—the key to meeting Canada’s climate commitments?

This essay was commissioned to inform the research and recommendations in our report Sink or Swim: Transforming Canada’s economy for a global low-carbon future, as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

I am an Anishnaabe Kwe from Nipissing First Nation, an electrical engineer turned CEO of a business council. I first enrolled in electrical engineering because I wanted to support Indigenous communities to be inclusive participants in the energy sector. While my career has changed in the last few years, my focus is still on enabling inclusive participation of Indigenous communities and businesses, and I still believe wholeheartedly in the opportunity that exists for these communities and businesses in the clean energy transformation that is coming.

Prior to moving to the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (CCAB), I managed the First Nations and Métis Relations team at the Independent Electricity System Operator in Ontario from 2014 to 2018. Over those four years, we worked to build requirements to ensure that First Nations and Métis communities in Ontario were active partners in the energy sector. Much of this work happened through renewable procurement. We adjusted policies and program documents to ensure that the procurement of renewable energy was not only accessible to Indigenous communities but also equitable. With each iteration, more communities applied for projects, either as the sole developer or through a partnership. At completion, close to half of the First Nation communities and the Métis Nation of Ontario were partnered on renewable projects through one of those procurements.

The results of our work were very promising, but there was, and still is, a lot more work to be done. There were several communities that wanted to partner or build projects but were not successful due to limited transmission capacity, associates not understanding true partnership or collaboration, or in some cases being constricted by the Indian Act, which limits the control of a First Nation to make decisions about their own land. Had we known all the challenges at the outset, accounted for them in the design, and provided support for communities to be better prepared to respond to procurement opportunities, I am certain that many more communities would by now be generating power for, and revenue from, the grid. Sharing the challenges and feedback from communities can enable community leaders, regulators, proponents, and policy makers in all provinces and territories to accelerate the clean energy transition in ways that support and strengthen Indigenous communities and businesses.

There are still many opportunities for Indigenous partnerships on energy projects and for energy companies to support the growth of the Indigenous economy, both in Ontario and across the country. To be blunt, if proponents, policymakers, and potential partners do not consider Indigenous partnerships or build policies for Indigenous ownership, further development in the clean energy sector will be stalled.

At CCAB, we are seeing the opportunities multiply in this sector. Indigenous communities across the country are building and partnering on projects in the clean energy economy. There are currently over 60,000 Indigenous businesses in Canada, and the Indigenous economy is growing at a significant rate. Over 35 per cent of these businesses are operating in construction, professional, manufacturing, and scientific and technical services—all of which are current participants in the energy sector.

Indigenous communities across the country are building and partnering on projects in the clean energy economy.

Notably, CCAB research indicates that Indigenous Peoples are creating new businesses at nine times the rate of non-Indigenous peoples in Canada, and that Indigenous business owners increasingly recognize the importance of innovation (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2019). More than six in ten (63 per cent) introduced either new products or services, or new processes, into their business in 2016, up significantly from 49 per cent in 2010 (Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, 2016). Additionally, there are over 10 energy providers across the country enrolled in CCAB’s Progressive Aboriginal Relations program—demonstrating their commitment to employ, procure, support, and build relationships with Indigenous Peoples.

The interest, the drive, and the businesses are growing, representing an incredible opportunity to meaningfully include Indigenous communities and businesses in Canada’s energy sector and the transition to a clean economy. While several partnerships were built as a result of provincial government policy, we have also seen projects built as a result of corporations righting their past wrongs, such as the Peter Sutherland Generating Station, as well as organizations like NRStor prioritizing building strong relationships with Six Nations of the Grand River on the Oneida Storage project.

Peter Sutherland Generating Station

In March 2017, Ontario Power Generation (OPG) and their partner Coral Rapids Power, a wholly owned subsidiary of Taykwa Tagamou Nation (TTN), completed the Peter Sutherland Sr. Generating Station. The project began with a resolution of the past grievance settlement between TTN and OPG in relation to other OPG hydro projects built in the First Nations’ Traditional Territory. A source of clean, reliable, electricity, the station is located at New Post Creek, about 75 kilometres north of Smooth Rock Falls, within the traditional territory of TTN, who remain 35 per cent equity partners in the station. Named after a respected TTN community elder who passed away in 1998, the station has two units that generate 28 megawatts of renewable, low-cost electricity—enough to power about 28,000 homes. The partnership resulted in more than $50 million in contracts for TTN businesses and about 50 TTN members worked on the project.

Oneida Energy Storage LP

The Oneida Energy Storage Limited Partnership is a joint venture between NRStor Inc. and Six Nations of the Grand River Development Corporation. It is a concrete example of an Indigenous renewable energy partnership with considerable potential to contribute to Canada’s energy evolution. The Six Nations of the Grand River Development Corporation is no stranger to renewable energy and the equal partnership that has been built is a prime example of the benefits of community capacity building. With support from the Canada Infrastructure Bank, Oneida Energy Storage LP and a team of industry leaders are completing a project analysis for what would be the largest energy storage facility in Canada. This project has the potential to provide clean, reliable power capacity by conserving renewable energy during off peak periods and releasing it into the Ontario grid once energy demands reach their peak. In addition, the Oneida Energy Storage LP will create internship opportunities for Six Nations community members and result in training and employment opportunities.

Ontario Renewable Energy Procurement Programs

From 2009 to 2018, Ontario procured renewable energy through two major programs: the Feed-In-Tariff program and the Large Renewable Procurement program.

The Feed-In-Tariff program was introduced in 2009 and went through five iterations. It was a standard-offer program with a set price dependent on the fuel type. Each iteration aimed to keep down the costs to the ratepayer, and to apply feedback and lessons learned from previous procurements while maintaining policy objectives. A priority of the government at the time was to ensure that Indigenous communities were active participants in Ontario’s energy sector. By the last iteration, Feed-In-Tariff 5.0, the following support measures were included to support equal participation of Indigenous communities:

- Security payments, which were required at several points in the process, were set lower for projects controlled by an Indigenous community—to recognize the barriers that communities face to access financing, especially in a highly regulated and high-entrance-cost industry.

- In addition to receiving the standard Feed-In-Tariff price, Indigenous projects received a better price per kilowatt hour proportionate to the amount of equity ownership by the Indigenous community.

- In each procurement, a certain number of megawatts were set aside for projects with greater than 50 per cent Indigenous ownership.

- Priority points were assigned to projects that received a support resolution from the neighbouring Indigenous community or an Indigenous community host.

- An extension was given to the milestone date for operation of projects on First Nation land due to the inability of First Nations to lease land to potential proponents without approval of the federal government.

The Large Renewable Procurement program was introduced in 2013 as a competitive procurement process for projects greater than 500 kilowatts. The program retained many of the similar provisions as the Feed-In-Tariff program. It also included mandatory requirements for proponents to engage with local communities and gave priority to proponents who demonstrated community engagement over and above the mandatory requirements, such as a Band Council Resolution or proof of Indigenous equity participation.

- At the completion of the first round of Large Renewable Procurement, 16 contracts were offered equal to 454 megawatts. Thirteen of those projects had a First Nation partner. Five of them had more than 50 per cent equity participation.

- The successful projects at the completion of the Large Renewable Procurement program saw 15 unique Indigenous communities participating, with two of the projects involving joint partnerships with six remote First Nation communities. The six remote Indigenous communities rely solely on diesel generation and had planned to use the revenue to build clean energy systems in their communities.

As the first Large Renewable Procurement program in Ontario, those are excellent results, but this success was largely due to various iterations and progress made within the Feed-In-Tariff program. An immense amount of progress was due to additional provincial programs that enabled Indigenous communities to build capacity, supporting this growth by covering costs for partnerships and project development. These programs include funding for Indigenous communities to:

- Establish community energy plans through an assessment of options and engagement with their members.

- Support costs in relation to legal and financial requirements to enter into partnerships.

- Support an individual in the community to focus on energy projects and partnerships.

- Support community engagement processes and readiness for future or potential renewable projects.

Unfortunately, with a change in provincial government, a number of those Large Renewable Procurement projects were cancelled. However, there are still opportunities in Ontario and across the country for potential partnerships in transmission, energy storage, and innovative technologies. If I were designing those programs today, I would make three recommendations to any group seeking to foster effective Indigenous partnerships:

1. Build time into the process

It is not enough to incent proponents to partner with communities or vice versa. You need time to build relationships and for communities to discuss the impacts and engage their membership, and it must be built into the process. Meaningful partnerships require trust and relationship building, and we all know that those things take time to develop.

In my own community—which is very well established and has seen considerable economic growth—the decision to use revenues from money held in trust to invest in renewables was made through many community engagement sessions. They were held in person, both off- and on-reserve and online. A decision to move forward was only made once votes were ratified by members. The decision to choose a partner was also made through many in-person community engagement sessions. This was a significant investment of time and money for community staff and elected officials, whose portfolios not only include energy or economic development but most often mental health, education, housing, and elder care as well.

As I said, the Large Renewable Procurement process in Ontario had requirements with respect to engagement with neighbouring communities. Once approved through the request-for-quotes stage, a list of qualified proponents was made public so communities can have some certainty that the proponents are viable partners. However, the feedback received from communities during my time at Independent Electricity System Operator found that although the request-for-proposal process was six to eight months long, many communities reported that they were bombarded with requests to partner in the four-week period before the deadline.

2. Build capacity and ready Indigenous communities for partnership

I heard from many communities that they were not equipped to respond to requests to partner in the timelines the proponents required. While we can continue to assert that proponents must take time to build meaningful relationships, this is extremely difficult to enforce. So how do we better prepare communities for what is coming? We need to ensure early engagement on energy and infrastructure planning and potential projects so that communities are as informed as the potential proponents—or, even better, that they become the proponent.

Indigenous Peoples have been stewards of the environment since time immemorial. The interconnectivity among Indigenous communities, their cultures, and ways of life with the land are reflected in laws and constitute the basis for Indigenous rights as well as responsibilities. Indigenous environmental values, their consideration of the impact on water and treaty rights, and adherence to natural laws are strikingly different than most potential partners. We often say this, but I do not think developers really grasp just how different these concepts are for Indigenous Peoples. For example, what non-Indigenous corporation considers how a project or decision will impact their seventh generation—that is, the impact on descendants that are going to be born in 2215? These impacts take time to consider and evaluate. Decisions are particularly difficult with the introduction of new technologies without historical precedent, such as nuclear waste disposal. If we can resource communities to advance this work, then we are better enabling them to make good decisions for our future when a project becomes a reality.

Additionally, communities have said that they require the necessary support to respond and participate in the conversations necessary to enter into equity projects. Such support might include funding for a full-time energy worker in the community, for legal and financial fees to evaluate financial and ownership models, or for community engagement plans or community governance.

3. Do not be afraid to ask questions

I know sometimes, particularly with Indigenous communities or Indigenous issues, people are worried about saying the wrong thing or asking the wrong question for fear of causing offence, but that has only served to stall conversation, our collective learning, and the country’s progress. Now more than ever, we need to ensure we keep the conversation going

One final consideration: Indigenous people are not one-dimensional. We are not just protestors or just environmentalists; we are artists and engineers and doctors and lawyers. We have been entrepreneurs and business leaders since before Confederation, trading and negotiating, and moving products from nation to nation. We will continue to do so with the needs and well-being of the next seven generations in mind.

Chi Miigwetch

Tabatha Bull is an Anishnaabe Kwe from Nipissing First Nation. As President and CEO of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business she is committed to help rebuild and strengthen the path toward reconciliation and a prosperous Indigenous economy to benefit all Canadians. An electrical engineer, Tabatha informs Canada’s energy sector by participating on the boards of Ontario’s electricity system operator IESO, the Positive Energy Advisory Council, the MARS Energy Advisory Council, and the C.D. Howe Institute’s Energy Policy program.

Protecting Biocultural Heritage and Land Rights

Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

1. Introduction and context

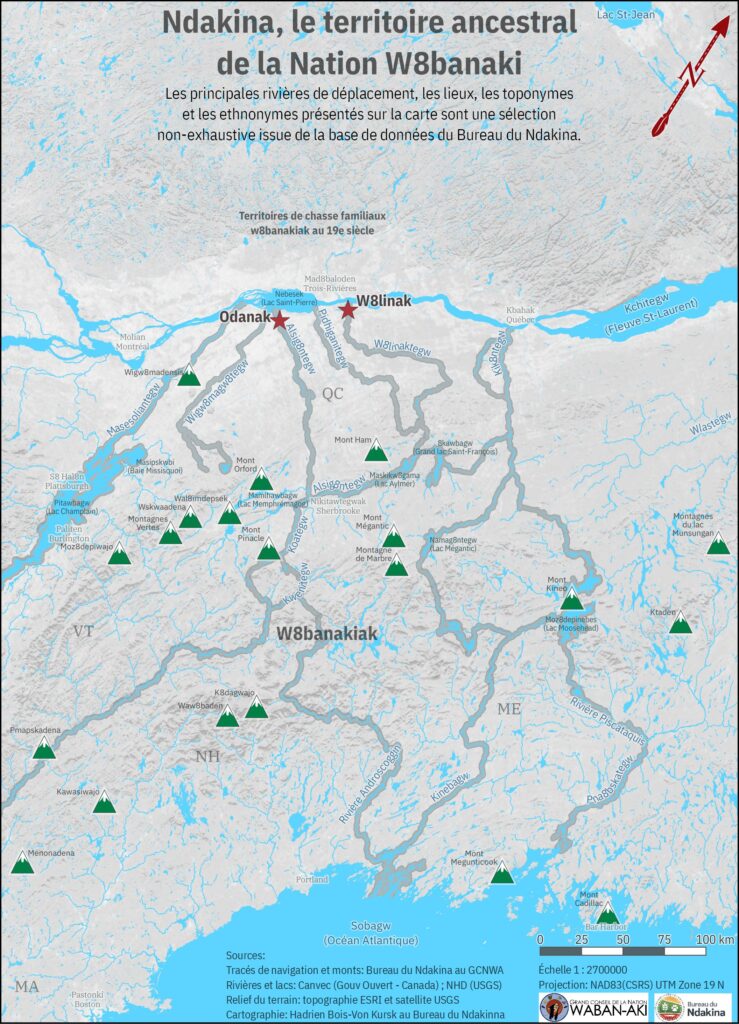

The Ndakina, the ancestral territory of the W8banaki 1 Nation, extends approximately from Akigwitegw (the Etchemin River) in the east to Massessoliantegw (the Richelieu River) in the west, and from the St. Lawrence River in the north to the Atlantic coast and the states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and part of Massachusetts in the south (see Figure 1). Currently, the Nation has more than 3,000 members in two communities, Odanak and Wôlinak. The Ndakina Office 2 works to safeguard the Ndakina in the long term, mainly via: 1) promoting and defending the Nation’s rights and interests on the Ndakina; 2) representing the Nation in territorial consultations and land claims; 3) documenting, preserving, showcasing and passing on the knowledge of the W8banakiak; and 4) supporting the Nation in fighting and adapting to climate change. To fulfill this mission, the Office favours an approach of territorial affirmation rather than comprehensive land claims.

The right of the W8banakiak to traditional activities, cultural continuity, and self‑determination is connected to territorial integrity. Research on modern use and occupation of the land conducted by the Office and for specific groups in the Nation (for example, youth or women) has clearly demonstrated this (see, for example, GCNWA, 2016). This research has also shown that human activities such as agricultural intensification, land privatization and the pressure exerted by commercial and sport practices have significant impacts on the Nation’s traditional activities (hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering, etc.), knowledge, health, and, ultimately, stewardship capacity. Despite these significant constraints and albeit with difficulty, the W8banakiak have been able to continue their ancestral activities over the years (Gill, 2003; Marchand, 2015).

To these pressures, climate change has now been added. The Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki launched projects focused on adapting to climate change in 2014–2015, based on an initial plan 3 (GCNWA, 2015).

As part of this initiative, members reported on how climate change is affecting the abundance, distribution, and health of species of wildlife, fish, and plants. One major effect is that, for many, the cycle and timing of hunting, trapping, and fishing have been disturbed; this varies between seasons but has intensified over the years. For example, hunters and trappers must stagger or sometimes cancel their activities. Winter travel has become more dangerous because of the fragility of the ice. Populations of some native species (for example, yellow perch) have dropped, and their meat may be of lower quality due to the proliferation of parasites that higher temperatures can bring. The quality and quantity of certain medicinal plants have also been negatively affected by higher temperatures, as when some medicinal plants dry out, they produce less essential oil. The proliferation of exotic invasive species is also an issue. Another major effect that many have observed is disrupted water flow and accelerated bank erosion, especially for Alsig8tegw (St. François River) and W8linaktegw (Bécancour River).

Overall, these changes have had major impacts on the way of life of many members of the Nation who practice sustenance, ritual, or social activities. The fact that these activities are vulnerable to climate change significantly reduces members’ cultural continuity and ability to transmit knowledge and practices, which ultimately impacts their health.

2. Assessing climate change adaptation initiatives

This case study is focused on two specific aspects of climate change adaptation initiatives: 1) project management, and 2) program governance and funding. What factors help a climate change adaptation project maximize its positive ecological and social impact, and what characteristics mean programs can help communities successfully adapt to a warming cliamte?

We find that the Ndakina Office has prioritized access to the land and cultural continuity through three projects to prevent and mitigate the degradation of biological and cultural resources: 1) Evaluating the reproduction success of lake sturgeon and restoring its habitat (2012–2018), 2) Evaluating the impact of climate change on the availability of medicinal plants and the proliferation of exotic invasive species in a health context (2018–2019), and 3) Evaluating erosion and flood risks on the banks of Alsig8tegw (St. Francis River) and W8linaktegw (Bécancour River)] (better known as the Erosion Project, 2019–present). These three examples were selected because they identified similar vulnerability factors and have taken similar approaches to community engagement.

3. The three cases

3.1. Management of species of cultural importance: lake sturgeon

The W8banaki Nation continues to have an important cultural connection with the lake sturgeon4 (the emblem of the Odanak community) and in particular the populations of the St. Lawrence River and its watersheds. The fish remains part of the Nation’s diet, and is especially prized as a dish for community gatherings. For 10 years now, the Odanak Land and Environment Office5 (known by its French acronym BETO) has conducted in‑depth documentation of the reproduction of the lake sturgeon in the St. Francis River, near the Drummondville hydroelectric dam where there is a spawning ground, with a view to proposing avenues for conservation efforts. The resulting research has shown that poor water flow management by hydroelectric stations has a negative influence on the sturgeon’s reproductive ecology, particularly during periods of migration and spawning (Dufour-Pelletier et al., 2021; see also Clément-Robert et al., 2016). Extreme weather events such as droughts, floods or heavy total precipitation further threaten the reproduction and long‑term survival of lake sturgeon in the area (COSEWIC, 2017).

In this context, BETO’s initiatives to monitor lake sturgeon reproduction and recovery have had a significant impact. Site management and water flow management plans have been recently set up, as has a sanctuary area where sport fishing is prohibited before the spawning season. These efforts were made in partnership with major regional actors such as Hydro‑Québec and the Minister of Forests, Wildlife, and Parks. Such protection and management measures are a hopeful sign for the species’ reproductive success and survival rate in the future. On the technical side, the BETO has developed advanced monitoring and management techniques. In a meeting, the project manager strenuously insisted that testimonials from certain W8banakiak fishers and knowledge holders were important for identifying and characterizing research sites of interest for initial work, planning and following up.6 In this sense, the efforts regarding the lake sturgeon are an excellent example of the integration of W8banakiak knowledge with western science. On the socio‑economic side, the long‑term project meant that a good dozen W8banakiak could be hired and trained, deepening the cultural ties between members and this emblematic species (see Photo 1). Furthermore, in material and financial terms, the funds generated helped to consolidate and grow the BETO, increasing its credibility and legitimacy with other regional actors.

3.2. Managing medicinal plants and exotic invasive species

In various studies, members have consistently stated that the intensification of climate change is disrupting the distribution and quality of plant species in southern Quebec. This disruption includes the proliferation of certain invasive species (for example, common reed and Japanese knotweed), which compete with valued species such as cattails or yarrow (GCNWA, 2015, 2016). Climate change also lowers the quality of important indigenous plants, as global warming leads them to dry out more quickly. These problems are of significant concern. At issue is not just a resource, but also members’ capacity to transmit knowledge and educate future generations. This is all the more concerning given that the W8banakiak have suffered the disruption of their ethnobotanical knowledge due to the colonial past and divisions between generations that they experienced; despite these challenges, interest in this knowledge and these practices continues (GCNWA, 2016).7 The project had two objectives regarding these issues: 1) to document and promote the availability and variety of medicinal plants in communities in a time of climate change, and 2) to promote the transmission of knowledge about medicinal plants, traditional medicine, and climate change.

The project promoted intergenerational ties by directly connecting Elders with younger people, which led the younger participants to develop a strong interest in traditional medicine.

The project had several positive outcomes. Interviews with knowledge holders gave researchers a better understanding of their perceptions of climate change’s impact on medicinal plants and ethnobotanical knowledge. A transect inventory method developed by the BETO, the BETW, and knowledge holder Michel Durand Nolett, used especially in wetlands and forested areas, helped provide more in‑depth data on the zones prioritized by the two communities and on plant species of seasonal interest. Vulnerable areas were identified by cross‑referencing the distribution of plant species of interest with that of EIS. The study also had a capacity‑building and awareness‑raising component: knowledge holders led sharing workshops, a community garden was set up, a booklet and videos on medicinal plants were developed, along with other efforts to raise awareness of EIS‑related issues (see Photo 2). The project promoted intergenerational ties by directly connecting Elders with younger people, which led the younger participants to develop a strong interest in traditional medicine. For example, a young Abenaki woman working at the BETO has now been approached about taking over the transmission of such knowledge about ancestral plants.

3.3. Assessing erosion and flood risks in the context of climate change

Water systems have always been dwelling places for the W8banakiak. Alsig8tegw (the St. Francis River) and W8linategw (the Bécancour River) are key witnesses of the Nation’s presence in Quebec, first semi‑permanent and then permanent. Many locations along the banks of these rivers have been recognized as important places of occupation and registered by Quebec’s Minister of Culture and Communications. Oral and written sources and settlement patterns have also identified other sites of great potential interest (for example, portages, campsites, ceremonial sites or burial sites). Today, many W8banakiak still practice activities on the same rivers, including hunting, fishing and gathering. However, climate change is accelerating erosion along Alsig8tegw and W8linategw (Roy and Boyer, 2011; Tremblay, 2012). Members confirmed this trend in interviews conducted for the climate change adaptation plan (GCNWA, 2015). Erosion and sedimentation can have major impacts on water quality and fish habitats, and therefore fishing. They can also damage important archaeological and cultural sites.8 The first phase of the project to assess erosion and flood risks along the banks of the rivers Alsig8tegw and W8linaktegw in the context of climate change established the extent of the degradation and documented its impact on the archaeological and cultural heritage of the region.

From this work, observation and recorded data have tracked erosion mechanisms in dozens of zones with archaeological or cultural potential, the implementation of erosion vulnerability indices, and the creation of tracking sheets (see Photos 3 and 4). This risk assessment should help the Nation to better plan and manage the efforts needed to mitigate erosion impacts and protect these sites. As in the lake sturgeon monitoring project, some W8banakiak recognized for their knowledge of navigation were consulted to help researchers understand the history of, and changes in, the hydromorphology and ecology of the two rivers. Beyond archaeological considerations, one field employee reported that the project allowed them to explore the territory in greater detail than usual, because of the study’s intersections between biophysical features and topological features. This work helped to build the capacity of the archaeology and biology teams and opened the door to developing joint projects. Once again, BETO and BETW participation in this project and its fieldwork activities provided jobs to members of the Nation.

4. Lessons learned and best practices

4.1. Lessons learned for climate change adaptation advance planning

As stated above, the GCNWA launched its climate change and adaptation efforts with the help of a provincial program to support the creation of climate change adaptation plans. Since the funding was short‑term (one year, after a long approval period), the program excluded all implementation activities, preventing any application of a longer‑term and more promising vision.9 Members of the Ndakina office and the BETO and BETW pointed out many other gaps as well, including the limited scope of the consultation and the top‑down plan implementation approach that involved excessively close monitoring of the process and delays in execution. The result of this process was a rigid and standardized plan. It was difficult to integrate members’ key concerns, such as traditional Indigenous knowledge, which was dismissed in favour of measurements and quantification. (For example, little consideration was given to observation of ice or snow.) In retrospect, the focus on exhaustive data collection, analysis, and written reporting was deemed to be distant from members’ more concrete and practical priorities.

In response to this institutional context, and although the climate change adaptation plan provided significant information and orientations that directly led to some climate change adaptation projects, the Ndakina Office, the BETO, and the BETW launched an adaptation program that was more closely aligned with the priorities that members had expressed in various consultations on the use and occupation of the land, working with the opportunities available at the time. This is a more bottom‑up approach to planning.

4.2. Lessons learned for managing climate change adaptation projects

In our experience, when developing projects, it is important to take into account ecological, social and cultural dimensions and the Nation’s interests for the Ndakina. Good starting hypotheses for research work and correct diagnosis also require appropriate mobilization of scientific and traditional knowledge. The participation of knowledge holders and members (particularly Elders and youth) as advisors and for validation is especially useful for achieving this. Greater involvement of the Nation’s members and elected leaders remains a constant challenge. We have observed that they will get involved more directly in projects that provide them with tangible benefits (for example, jobs or salaries, access to equipment, or training or learning opportunities).

On a broader scale, we have seen that strong collaboration between the Nation’s administrative units and regional actors has allowed for a deeper analysis of issues and for more ambitious initiatives. In the two sections that follow, we will see that additional factors, such as the institutional and financial context, may be catalysts or obstacles for projects.

4.3. Lessons learned for climate change adaptation governance and funding

A project’s success depends greatly on the source and nature of its funding. The issue here lies in defining what “high‑quality” funding means for First Nations communities. The experiences of the three projects presented here show that quality funding must be sufficient, stable, flexible, available in cash and in kind, and tailored to community needs.10 Obviously, the volume, stability and long‑term continuity of funding help to ensure greater autonomy in planning and implementing climate change adaptation. For example, wildlife management and inventory work for the lake sturgeon predate the climate change adaptation plan and benefit from substantial multi‑year funding from the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk that allows for consistent program‑related decision making. This continuity of funding makes it possible to plan long‑term activities and thus maximize their impact. It is no less important, however, to obtain more ad hoc funding, given that the land and environment offices are small organizations. Such funding allows them to round out work teams, provide competitive wages to members of the Nation, and invest in up‑to‑date equipment.

In all three cases, feedback emphasized the value of funders leaving a certain amount of flexibility to project heads, resulting in greater independence in articulating the project and its orientations. Of the three projects, two were nearly not funded because they did not match the initial scope of the programs. For the project on medicinal plants done in collaboration with Indigenous Services Canada and Health Canada, it was necessary to negotiate the project’s eligibility before funding was obtained, which pushed back the approval and start‑up phases. The Erosion Project ran into similar difficulties. The Department of Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs deemed work with an archaeological component to be ineligible for funding. The application was refused at first, but accepted after discussion and negotiation of the program’s scope.

A certain degree of independence is not the same thing as carte blanche. The Ndakina Office administrators we met with recognized the value of effective follow‑up. They appreciated when funders went beyond their administrative role to provide technical contributions as well. Another aspect of follow‑up they mentioned was the need to distinguish between the importance of ensuring project compliance (for expenses or deadlines, for example) and the importance of providing opportunities to exchange information and learn, especially between project leaders and the funder and between different communities funded (Indigenous and non‑Indigenous). Certain GCNWA‑led projects have a strong potential for being duplicated in or transferred to other communities or contexts, particularly innovative projects and those that were notably successful. Similarly, the Ndakina Office considers that, in current funding programs, the component for the community of practice to learn and share results is a poor relation of sorts, and that platforms showcasing successful Indigenous projects are extremely rare if not non‑existent.

In our experience, available funding must be designed in a specific or targeted manner for Indigenous communities (or, more broadly, for small rural communities). Otherwise, it is difficult for small administrative bodies like the Ndakina Office or the BETO/BETW to submit competitive applications. One possible solution would be to strengthen an association’s connections with regional organizations that have compatible visions and goals (for example, watershed organizations for the Erosion Project), to enable small organizations to seek more substantial funding. Other potential allies include major programs working to protect at‑risk species (such as the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk or the Quebec Wildlife Foundation), that set regional priorities each year. However, the species of cultural priority to the Nation (moose, lynx, yellow perch, lake sturgeon, etc.) rarely appear in those lists.11

The Nation’s sovereignty is negatively affected by this exclusion of key species from at-risk status. We believe that each nation must be able to define their own priority species for funding, but current federal mechanisms do not allow for such flexibility. This issue highlights the necessity of understanding the needs and priorities of each community and its organizations, so that proposed projects can be tailored to the local context and desires.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The integrity of the Ndakina is critical for the W8banakiak to effectively exercise their rights regarding self‑determination and the practice of traditional activities. Over the last few years in particular, members have shared their growing concerns about the impact of climate change on these rights (hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering, etc.). Climate change affects both the quality and the quantity of species of wildlife, fish, and plants. Such resources also have a high cultural value, so the fact that these activities are vulnerable to climate change also reduces the Nation’s ability to transmit its culture between generations. The climate change adaptation‑related planning and three cases presented here have helped to highlight these concerns and impacts. The concrete outcomes of the three projects include deeper BETO and BETW expertise on the socioecology of the Ndakina, connecting traditional Indigenous knowledge and modern science; greater technical and material skills; tangible benefits for members and knowledge holders; closer collaboration among members, administrative units, and a variety of regional partners; and stronger intergenerational ties to strengthen a culture of territorial stewardship in youth.

The factors that contributed to the three projects’ success in planning, funding, and execution have led us to make the following recommendations.

Community-engagement recommendations:

- Encourage research by communities. This allows them to mobilize their members, suggest good diagnostic measures, and set up efforts that are relevant to the community’s situation.

- Promote participatory approaches to interventions that include Indigenous knowledge and modern science, and consider socio‑economic benefits (wages, building technical capacities) as central elements of participation and inclusion.

- Encourage opportunities for networking in a spirit of collaboration between First Nations and regional actors whose missions and activities are often complementary with regard to sustainable environmental management.

Planning and funding recommendations:

- For climate change adaptation plans (an essential tool for conceptualizing the issues, objectives, efforts and key stakeholders to involve), consult with members widely and in an ongoing way, and ensure that the planning framework comes from the community rather than following a template.

- Provide Indigenous communities with recurring core funding so that they can both fight, and adapt to, climate change.

- Ensure that funding for climate change adaptation programs is more flexible and able to accommodate cultural, spiritual and other dimensions, to fit the more holistic First Nations understanding of the land.

- Adapt funding in certain sub‑sectors (such as species conservation) to communities’ specific needs and priorities.

- Ensure that funding options open the door to more technical support and to opportunities for learning and discussion among participating First Nations.

The W8banaki Nation is currently updating its previous climate change adaptation plan, which covered 2015–2020. We have learned a great deal from the adaptation projects carried out in the last few years, and have every hope that this plan will take a queue from more inclusive planning processes so that we can work to successfully ensure the long‑term integrity of the territory needed for the Nation’s cultural continuity and self‑determination.

About the authors

Rémy Chhem is Environmental Project Manager at the Ndakina Office and is currently completing a Ph.D. in international development at the University of Ottawa.

A member of the W8banaki Nation, Suzie O’Bomsawin has worked as Director of the Ndakina Office of the Grand Council of the Waban-Aki Nation since 2013. A resident of the Odanak community, she is also very involved in various organizations dedicated to the interests of First Nations.

Jean-François Provencher is Executive Assistant at the Ndakina Office, and holds a master’s degree in environmental management from the Université de Sherbrooke.

Samuel Dufour‑Pelletier is a biologist and Director of the Bureau environnement et terre d’Odanak.

References

Ndakina Office. (2020). Projet de recherche sur l’impact des changements climatiques sur la disponibilité des plantes médicinales et la prolifération d’espèces exotiques envahissantes pour les communautés d’Odanak et de Wôlinak dans un contexte de santé. Wôlinak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Clément-Robert, G., S. Gingras, M. Pellerin and R. Poirier. (2016). Enquête sur les sources de variation de débits de la rivière Saint-François durant la période de fraie de l’esturgeon jaune. Sherbrooke: Université de Sherbrooke.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). (2017[2006]). Assessment and Update Status Report on the Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in Canada. Ottawa: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, 124 p.

Dufour-Pelletier, Samuel, Émilie Paquin, Philippe Brodeur and Michel La Haye. (2021). “Reproduction de l’esturgeon jaune dans la rivière Saint-François : un exemple de participation des peuples autochtones à la conservation d’une espèce emblématique.” Le naturaliste canadien.

Dumont, P., Y. Mailhot and N. Vachon. (2013). Révision du plan de gestion de la pêche commerciale de l’esturgeon jaune dans le fleuve Saint-Laurent. Québec: Ministère des Ressources naturelles du Québec, 127 p.

Gill, Lucie. (2003). “La nation abénaquise et la question territoriale.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 33(2), p. 71–74.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2015). Plan d’adaptation aux changements climatiques – 2015. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2016). Étude de l’utilisation et de l’occupation du territoire de la Nation W8banaki, le Ndakina, et des connaissances écologiques traditionnelles qui lui sont associées dans la zone d’influence du projet d’oléoduc Énergie-Est de Transcanada. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki. (2021). Évaluation des risques d’érosion et d’inondation sur les berges des rivières Alsig8ntekw (Saint-François) et W8linatekw (Bécancour) dans un contexte de changements climatiques. Odanak: Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Marchand, Mario. (2015). Le Ndakinna de la nation W8banaki au Québec : document synthèse relatif aux limites territoriales. Wôlinak: Ndakina Office, Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.

Nolett Durand, Michel. (2008). Plantes du soleil levant Waban Aki : recettes ancestrales de plantes médicinales. Odanak.

Roy, A., and C. Boyer. (2011). Impact des changements climatiques sur les tributaires du Saint-Laurent. Presentation at the Colloque en agroclimatologie of the Quebec Reference Centre for Agriculture and Agri‑food (CRAAQ), Université de Montréal.

Tremblay, M. (2012). Caractérisation de la dynamique des berges de deux tributaires contrastés du Saint-Laurent : le cas des rivières Batiscan et Saint-François. Master’s thesis in geography, Université de Montréal.

Treyvaud, Geneviève, Suzie O’Bomsawin and David Bernard. (2018). “L’expertise archéologique au sein des processus de gestion et d’affirmation territoriale du Grand Conseil de la Nation Waban-Aki.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 48(3), p. 81–90.

Flood Vulnerability and Climate Change

1. Introduction

In a warming climate, Canadian cities are at risk of increasingly severe and frequent floods. Nearly 80 per cent of Canadian cities are built on floodplains, exposing populations, property, and infrastructure to flood risk (Golnaraghi et al., 2020; Jakob et al., 2015). The socioeconomic impacts of urban flooding are expected to worsen in the future because of population growth, expanding developments in flood-prone areas, and more frequent and severe extreme weather linked to climate change (Burn et al., 2016; Honegger & Oehy, 2016; Zhang et al., 2019).

Urban flood risk is the product of three interacting variables: the flood hazard, the exposure of people and assets, and the vulnerability of people and assets to flood impacts (Agrawal et al., 2014; Armenakis et al., 2017; L. Chakraborty, 2021). Most Canadian studies measure the extent and severity of flood hazards, along with the associated exposure of people, property, and infrastructure, but they often fail to include socioeconomic vulnerability. In the context of flooding, socioeconomic vulnerability refers to characteristics of a person or group that influence their capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from a flood hazard event (Cutter, 1996; Cutter et al., 2003; Wisner et al., 2004).

Studies from other countries indicate that socially vulnerable communities are disproportionately exposed to flooding and are more significantly affected by its impacts, but there has been little such analysis in Canada (J. Chakraborty et al., 2019; Collins et al., 2019). Spatial assessment of socioeconomic vulnerability is fundamental for identifying local flood risks (Cutter et al., 2013; Guillard-Goncąlves et al., 2015) and would build on existing data about flood hazards to assess the extent to which property and populations are exposed. Measuring the distribution of socioeconomic vulnerability in a community is critical for prioritizing scarce resources to protect those most at risk.

Methods for measuring socioeconomic vulnerability to flood risk in Canada are in their infancy. For this reason, a case study such as this one, which seeks to validate methods, identify data gaps, and draw out potential implications for public policy, can help to advance our understanding. Windsor, Ontario, was identified as a suitable focus due to its considerable exposure to flood risk. The results reveal hotspots of flood risk across neighbourhoods that have both a high concentration of socially vulnerable groups and a high exposure to flooding. We also consider potential policy interventions to address this geographically concentrated flood risk, with a focus on socioeconomic vulnerability.

Study objectives

- Understand the validity of data on socioeconomic vulnerability for measuring flood risk;

- Generate knowledge about the spatial extent and geographic distribution of flood risk across a large urban centre, and assess whether vulnerable communities are disproportionately exposed to flooding; and,

- Consider policy recommendations to address urban flood risk in ways that particularly protect the most vulnerable.

2. Methodology

This case study includes geospatial and quantitative analysis using national maps and datasets of flood hazards, residential properties, and census information (Table 1). The study area is the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) of Windsor, Ontario, Canada, and the unit of analysis is at the census tract level.12 Flood hazard extents were generated using JBA Risk Management’s 2018 Canada Flood Map, which quantifies fluvial (river-related) and pluvial (rain-related) flood risks at a 30-metre horizontal resolution.13 The 100-year recurrence interval—a flood the magnitude of which has a one per cent chance of occurring in any given year—was used as the hazard scenario (Holmes & Dinicola, 2010).

The number of residential properties in the flood hazard area was determined through GIS-based spatial analysis of a 2018 national dataset of address points generated by DMTI Spatial Inc. The socioeconomic vulnerability of exposed populations at these address points was calculated using Statistics Canada census data for socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and demographic variables. These data were organized using principal component analysis14 to construct a neighbourhood deprivation index that displayed variation in socioeconomic vulnerability across the community. The maps of residential flood exposure and socioeconomic vulnerability were combined to reveal the geographic concentration of flood risk across the CMA. Finally, a bivariate correlation analysis was performed to investigate whether socially vulnerable groups were significantly exposed to flood risk.

Table 1. Datasets

2.1 Study area

The population of the Windsor CMA includes the City of Windsor and the Towns of Amherstburg, LaSalle, Lakeshore, and Tecumseh. Between 2011 and 2016, the CMA population grew by 3.1 per cent, from 319,246 to 329,144. Windsor CMA is the 16th largest metropolitan area in Canada, larger than Saskatoon, Regina, Sherbrooke, St. John’s, and Barrie, but smaller than Victoria, Oshawa, Halifax, St. Catharines-Niagara, and London (City of Windsor, 2018, 2021). Windsor’s socio-demographic profile, key aspects of which are summarized in Table 2, is reasonably typical for a city of its size in Canada.

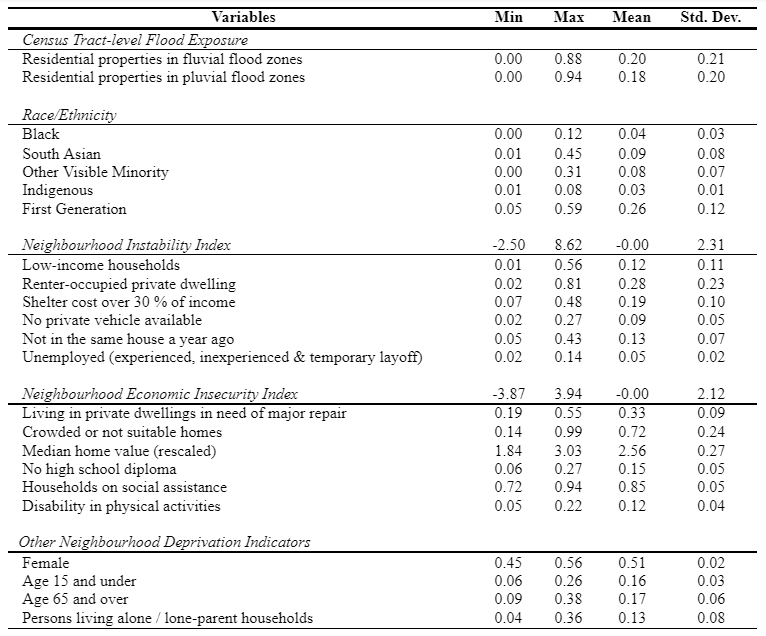

Table 2. Key Socio-Demographic Characteristics – Windsor CMA 15

Windsor is located in a low-lying area surrounded by Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River. Flooding has been a consistent problem for the city, with significant events in 2016, 2017, and 2020 (Battagello, 2020; Canadian Underwriter, 2017; CBC News, 2017). An extreme rain event in 2017, for instance, led to flooding in over 6,000 basements and caused $165 million in insured losses (Insurance Bureau of Canada, 2019). In response, the City of Windsor initiated a Sewer and Coastal Flood Protection Master Plan designed to assess and improve its flood mitigation strategies (CBC News, 2020). Given its exposure to flood risk and recent efforts to improve flood mitigation, Windsor is an ideal case for studying the value and implications of socioeconomic vulnerability analysis.

3. Findings and discussion

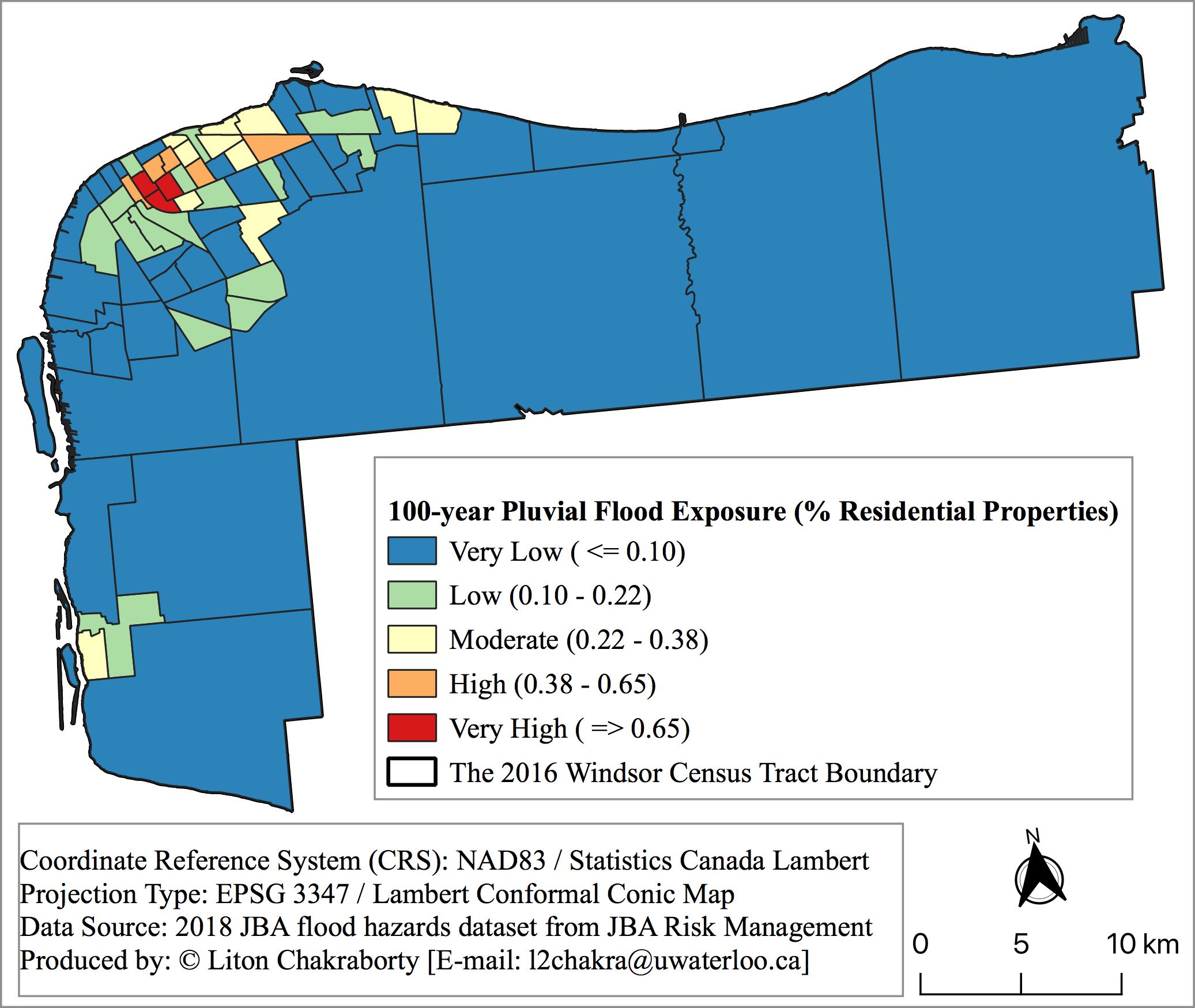

3.1 Flood exposure of residential properties

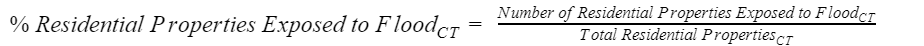

Established methods were used to determine flood exposure in three phases (Qiang, 2019). First, the number of residential properties was calculated for each dissemination block.16 Dissemination blocks were used for the property count because they are the smallest geographic units and they cover the entire Canadian territory, which comprises 489,676 dissemination blocks that have unique identifiers and attributes (Statistics Canada, 2018). Second, the total number of dissemination-block-level residential properties was aggregated to find the totals at the census tract level. Finally, the percentage of residential properties exposed to flood hazards in each census tract was calculated using the following equation:

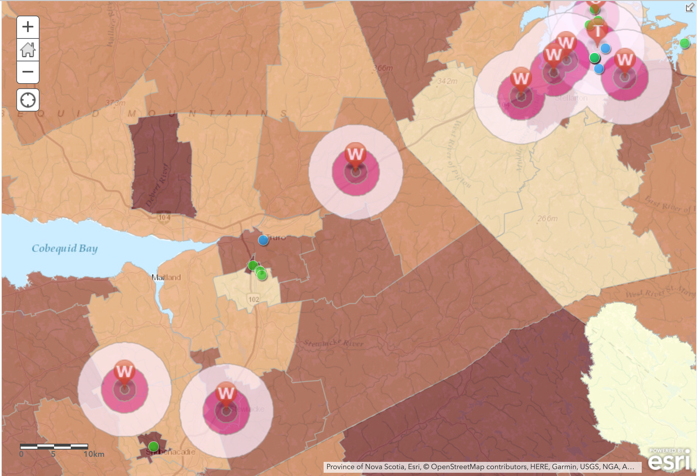

JBA’s flood hazard datasets were imported into ArcMap 10.7.1 to visualize flood-prone areas identified in the Canada Flood Map (Figure 1). Address points were layered onto the flood hazard map using DMTI’s residential address database (DMTI Spatial Inc., 2018).17

Figure 1. Fluvial and Pluvial Flood Hazard Exposure in Windsor CMA

Using the plotted outlines of residential properties, a binary analysis (1=yes; 2=no) was used to indicate whether a property intersected with the flood hazard area. The Windsor CMA contains 73 census tracts. There are 118,038 residential properties spread across these tracts, with at least 74 residential properties in each. The GIS-based exposure analysis results were summarized in a spreadsheet and then joined spatially with the census-tract-level cartographic boundary. This analysis revealed 26,722 residential properties (22.6 per cent) exposed to fluvial flood hazard and 19,582 residential properties (16.6 per cent) exposed to pluvial flood hazard.

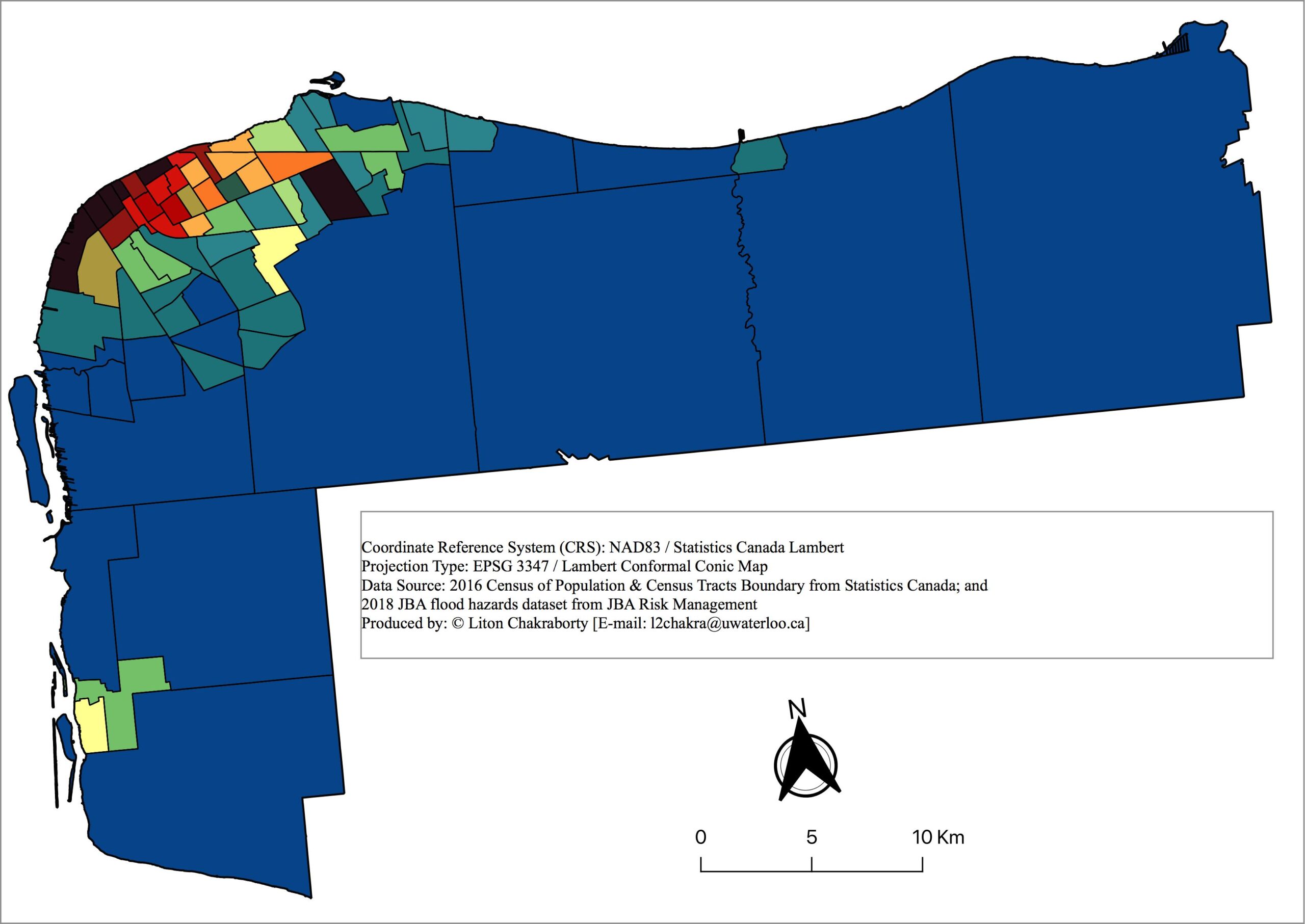

3.2 Socioeconomic vulnerability index

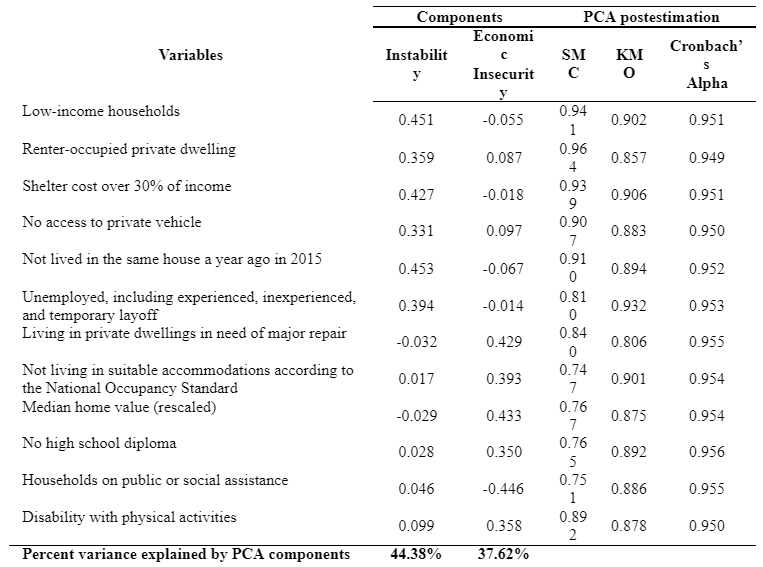

The socioeconomic vulnerability index was developed by compiling relevant indicators that measure a neighbourhood’s social deprivation relative to others. Deprivation indices are designed to capture the socioeconomic status of residents at a neighbourhood level (Bell & Hayes, 2012; Chan et al., 2015). Two deprivation indices—neighbourhood instability and economic insecurity—were most relevant for this objective.

The neighbourhood instability index defines levels of social deprivation by measuring the proportion of the population that would most struggle to recover from unexpected shocks or disruptions. Key indicators for this index include a lack of home ownership, insufficient income, high shelter costs relative to income, lack of a private vehicle, and precarious work or unemployment. By comparison, the economic insecurity index defines levels of social deprivation by measuring the distribution of the population that suffers from insufficient economic resources to sustain a median level of social welfare. People are considered economically insecure if they live in a dwelling requiring significant repair, inhabit a property valued lower than the Canadian median, lack a high school education, require social assistance, or suffer from a physical disability.

These indices provide an additional benefit for socioeconomic vulnerability analysis because they can be linked with demographic census data. Evaluating this relationship can determine whether historically marginalized or disadvantaged populations live in neighbourhoods with high levels of deprivation, in addition to hazard exposure. Descriptive statistics of variables used in the case study are reported in Table A.1 (Appendix A). Methods used to construct the neighbourhood deprivation index and ensure its validity and reliability are described in Appendix B.

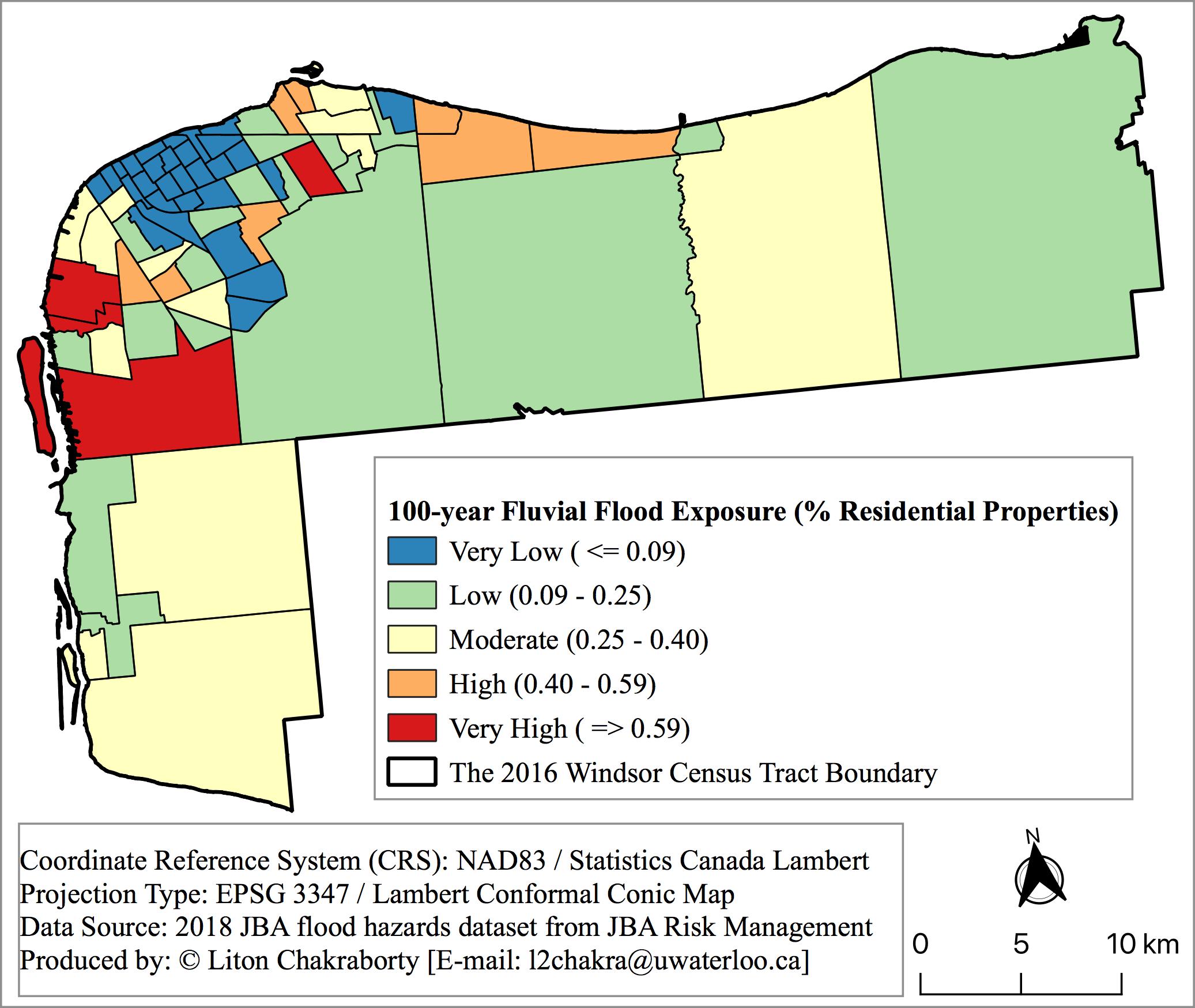

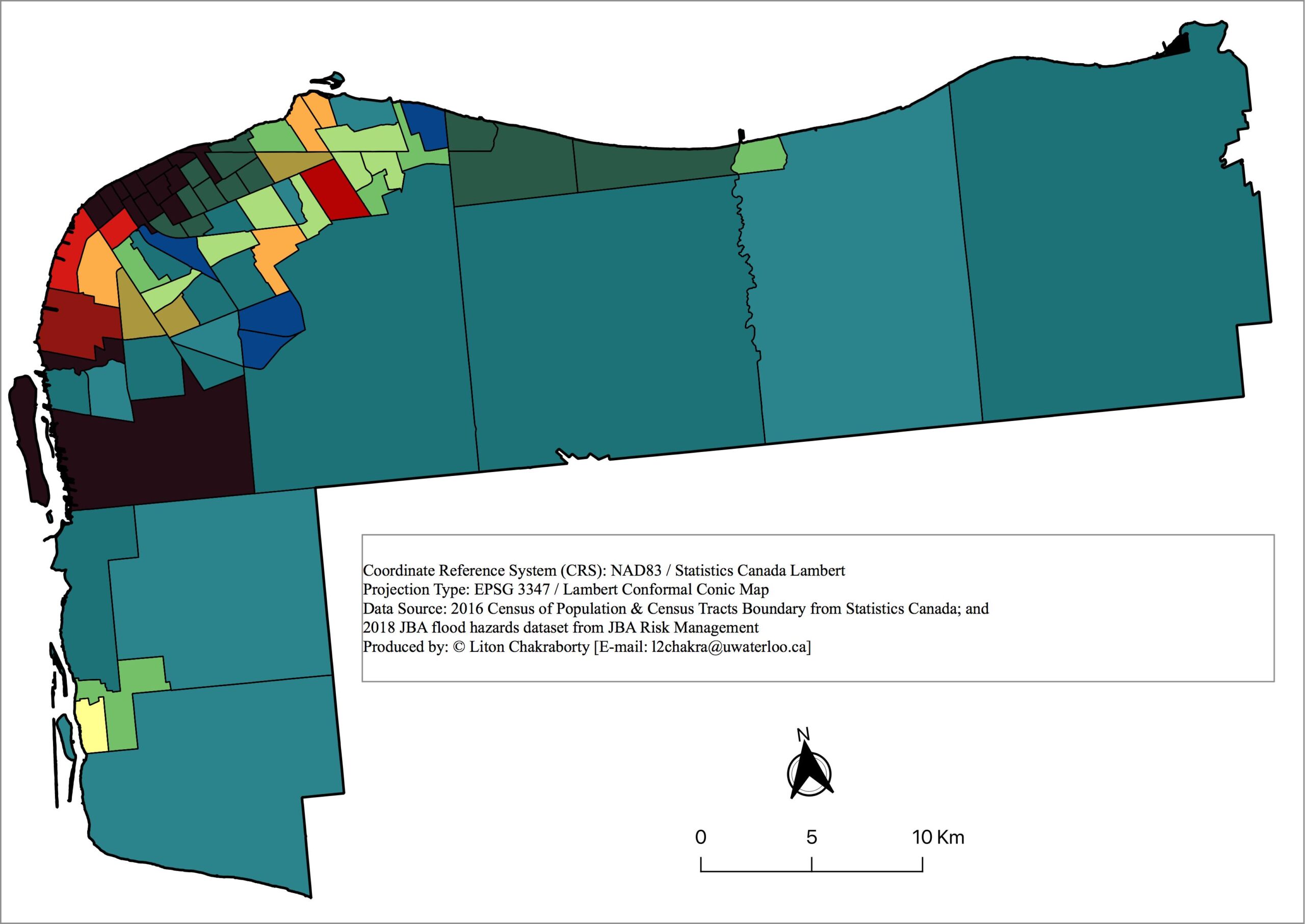

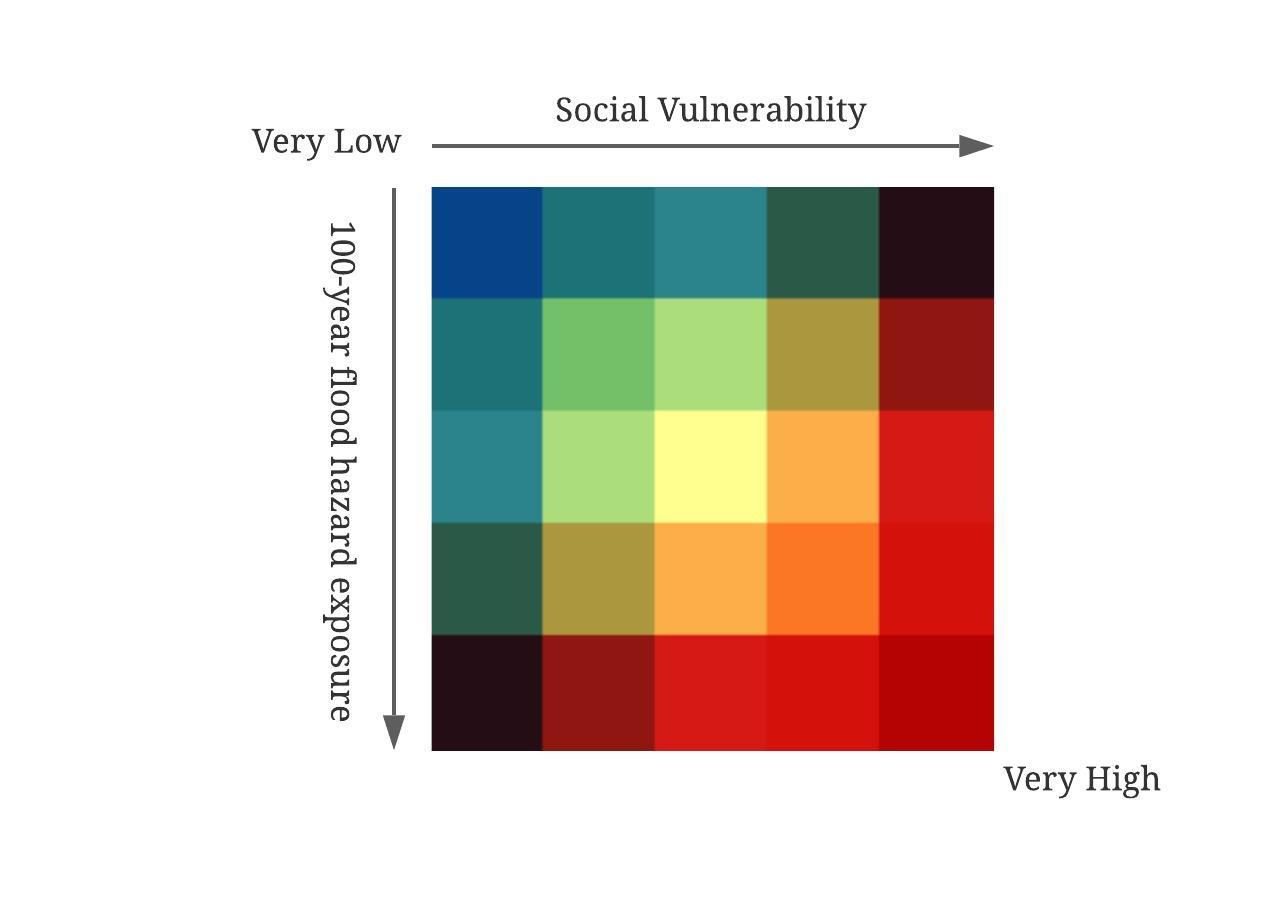

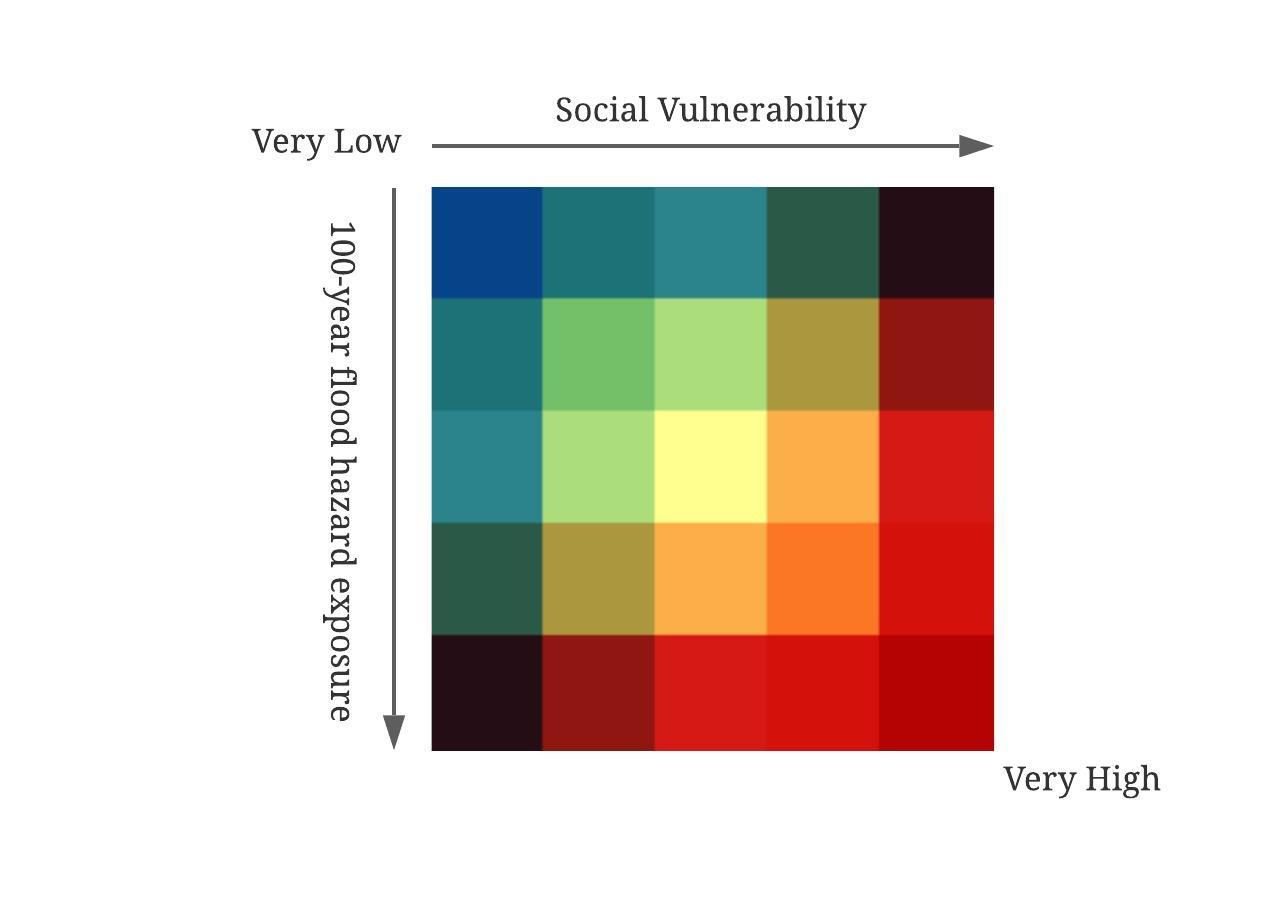

3.3 Hot spot analysis: The intersection of flood exposure and socioeconomic vulnerability

To identify areas at high risk of fluvial flooding, census tracts were classified and mapped into five categories and corresponding colour codes, including very low, low, moderate, high, and very high, based on the percentage of properties exposed to flood hazards (Figure 2a) and their socioeconomic vulnerability scores (Figure 2b). When these maps were combined, census tracts with both high or very high flood exposure and high or very high socioeconomic vulnerability were identified as hot spots of flood risk (colour-coded orange and red) (Figure 2c). The same process was repeated for pluvial flooding (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c).

Figure 2. Flood Risk Assessment for Windsor CMA (Fluvial)

| (a) Flood hazard exposure | (b) Socioeconomic vulnerability |

|  |

(c) Fluvial flood risk | |

|  |

Figure 3. Flood Risk Assessment for Windsor CMA (Pluvial)

| (a) Flood hazard exposure | (b) Socioeconomic vulnerability |

|  |

(c) Pluvial flood risk | |

|  |

These maps indicate that both flood hazard exposure of residential properties and socioeconomic vulnerability vary significantly across census tracts in Windsor CMA. Flood risk is concentrated in census tracts where residential properties and populations occupy inland flood zones (mainly the northeast corner of the City of Windsor). Riverine (fluvial) risk intersects with socioeconomic vulnerability in census tracts along the Detroit River, whereas surface water (pluvial) risk intersects with socioeconomic vulnerability primarily in dense downtown neighbourhoods.

3.4 Correlation analysis to inform flood-related inequities

To better understand flood-related environmental inequities, an analysis was conducted to determine correlations between flood exposure and several demographic variables that past research has associated with populations who experience social inequity and injustice. These variables are summarized in Table A.1 (Appendix A).

Based on census data, visible minority populations were grouped as ‘South Asian’, which included people of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Southeast Asian origin, or ‘Other’, which included people of Arabian, Latin American, and West Asian origin. The Indigenous population subgroup consisted of Aboriginal peoples and people with first ethnic origin identified as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis. Consistent with other Canadian environmental justice and equity analyses (Bocquier et al., 2013; Carrier et al., 2016b, 2016a; Dale et al., 2015), four other socio-demographic characteristics of the population were used in addition to race/ethnicity and neighbourhood deprivation indices. These included (1) per cent female; (2) per cent population aged 65 and over; (3) per cent population aged 15 and under; and (4) per cent population living alone.

Bivariate correlation coefficients are useful to evaluate whether certain populations that are historically marginalized also face disproportionate flood risk relative to other groups (J. Chakraborty et al., 2019; Grineski et al., 2015). This study used Pearson’s correlation coefficients to test the hypothesis that socioeconomically deprived groups disproportionately inhabit inland flood hazard areas, such as fluvial and pluvial flood zones of Windsor (Table 3).

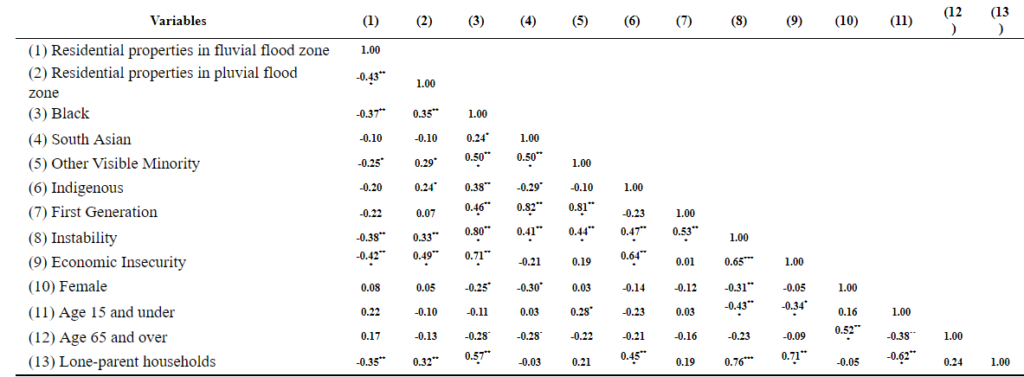

Table 3. Bivariate Correlation Coefficients and Statistical Significance

The correlation analysis revealed some statistically significant findings. As indicated by the correlation coefficient of 0.35** in column (2), for instance, Black households are more exposed to surface water (pluvial) flood risk than other population subgroups considered in this study. Indigenous peoples, other visible minorities, and lone-parent households are also highly exposed to pluvial flooding. In addition, pluvial flood risk is more significant in areas with higher neighbourhood instability and economic insecurity.

However, the same correlations were not found for riverine (fluvial) risk, as most of the coefficients in column (1) indicated either negative or statistically insignificant relationships between flood exposure and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics. For example, the coefficient of -0.37** in column (1) suggests Black households are at lower risk of fluvial flooding. Similarly, the coefficient of -0.20 for Indigenous populations in column (1) indicates that fluvial flood risk for Indigenous residents does not differ significantly from other population subgroups. These results possibly indicate that there are no significant racial and social disparities in exposure to riverine flooding in Windsor CMA. In other words, marginalized and racialized populations in Windsor are likely more exposed to pluvial flood risk compared to fluvial risk.

4. Policy implications for flood risk management

Incorporating measures of socioeconomic vulnerability into flood risk assessment offers several benefits. First, it provides a more comprehensive and robust picture of flood risk. In the case of Windsor, Ontario, the addition of socioeconomic vulnerability revealed that fluvial flood risk is concentrated in areas outside of those captured in more traditional methods that are limited to hazard exposure and physical vulnerability. The pluvial socioeconomic vulnerability analysis revealed that the distribution of risk is more complex and nuanced than what is captured by exposure assessment alone. Subsequent analysis on the distribution of risk across marginalized and racialized populations revealed the potential environmental injustice associated with flood risk in the Windsor CMA. Replicating this type of analysis in other municipalities could reveal different but equally important conclusions about how socioeconomic vulnerability intersects with flooding.

Better risk assessments can focus government policies on people and communities that would benefit most from flood risk reduction. For instance, riverine (fluvial) flood risk is the primary focus of federal and provincial programs, but surface water (pluvial) flooding is a rapidly growing source of risk as increasingly heavy rainfall in a warming climate overwhelms drainage infrastructure and water flows into streets and nearby structures (Gaur et al., 2019). As this analysis shows, even if people live far away from rivers, certain marginalized and racialized groups may experience high flood risk due to their exposure to surface water flooding and higher socioeconomic vulnerability.

The findings also suggest some implications for flood risk management policy. Flood risk communication and education, for example, aim to inform residents about flood risk and encourage household preparedness. Given the correlation between flood risk and marginalized and racialized communities, this analysis suggests that these communication and education campaigns should be tailored and targeted to reach the most vulnerable (Ziolecki & Thistlethwaite, 2019).

The risk assessment and mapping also offer a means to better calibrate non-flood related social programs and policies targeting these communities. As noted above, urban flood risk is the product of interaction between a flood hazard, the exposure of people and assets, and the vulnerability of people and assets to flood impacts. Whereas physical infrastructure can reduce the damage from flood events and purposeful planning can reduce exposure of people and assets, flood risk can also be reduced through social programs that target the determinants of socioeconomic vulnerability, such as low income, unemployment, and high shelter costs (Joakim & Doberstein, 2013; McEntire, 2012). For example, targeted funding made available through disaster assistance programs, subsidies, or vouchers could improve the affordability of flood insurance, which would improve the resilience of communities to recurring flood events, while reducing overall socioeconomic vulnerability.

5. Conclusion