No sector in Canada better exemplifies the challenges with carbon lock-in than oil and gas.

(For a primer on the complexities and consequences of carbon lock-in, check out Part 1 of this series.) The sector’s emissions profile, average asset lifespan, and global market and policy uncertainty for its products all combine to make carbon lock-in a uniquely severe risk.

However, there’s a new approach being proposed that gets to the heart of these challenges. If well-designed, the federal government’s forthcoming cap on Scope 1 and 2 oil and gas emissions could put Canada on a path to locking out lock-in in the sector.

Oil and gas’ carbon lock-in conundrum

Even though there have been marginal efficiency improvements over the past two decades, Canadian oil and gas production is still among the most emissions-intensive in the world. Oil and gas projects operate for 20 to 30 years or longer, meaning new projects could stretch to 2050 and beyond. And the sector is among the hardest to transition.

Furthermore, despite recent projections showing that global oil and gas demand will peak in the near future and decline thereafter, even under more conservative scenarios, there is still considerable uncertainty about the exact timing and scale of the transition. That uncertainty generates inertia that encourages the industry and politicians to advocate for and consider expansion in the sector which might not align with the sector’s net zero pathway.

For oil, carbon lock-in risk mostly arises from upgrades to existing assets because few new, “greenfield” oil projects are slated to come online as the energy transition accelerates. While there are promising technologies under consideration that could significantly drive down Scope 1 emissions, Canada’s oil sands heavy crude is currently the fourth most carbon-intensive oil globally, and many of the best available technologies cannot be applied to existing facilities. As multiple large oil sands producers acknowledge, they currently have enough proven and probable reserves to continue producing for almost three decades. That already stretches to 2050—and that’s without including “possible” reserves. Upgrading current facilities to either increase production in the near term or unlock new reserves in the long term could generate more lock-in.

For gas, lock-in risk might be more likely to arise from new facilities. Gas demand is expected to decline at a slower pace than oil in net zero scenarios, and gas can sometimes be a less carbon-intensive energy source than coal and oil. That seemingly makes it an attractive investment opportunity, especially with many European allies expressing short-term interest in Canadian gas. However, gas could be a “dead-end pathway,” delivering short term emissions reductions at the expense of long term net zero goals. It could also carry significant economic risk.

The knock-on costs of oil and gas lock-in

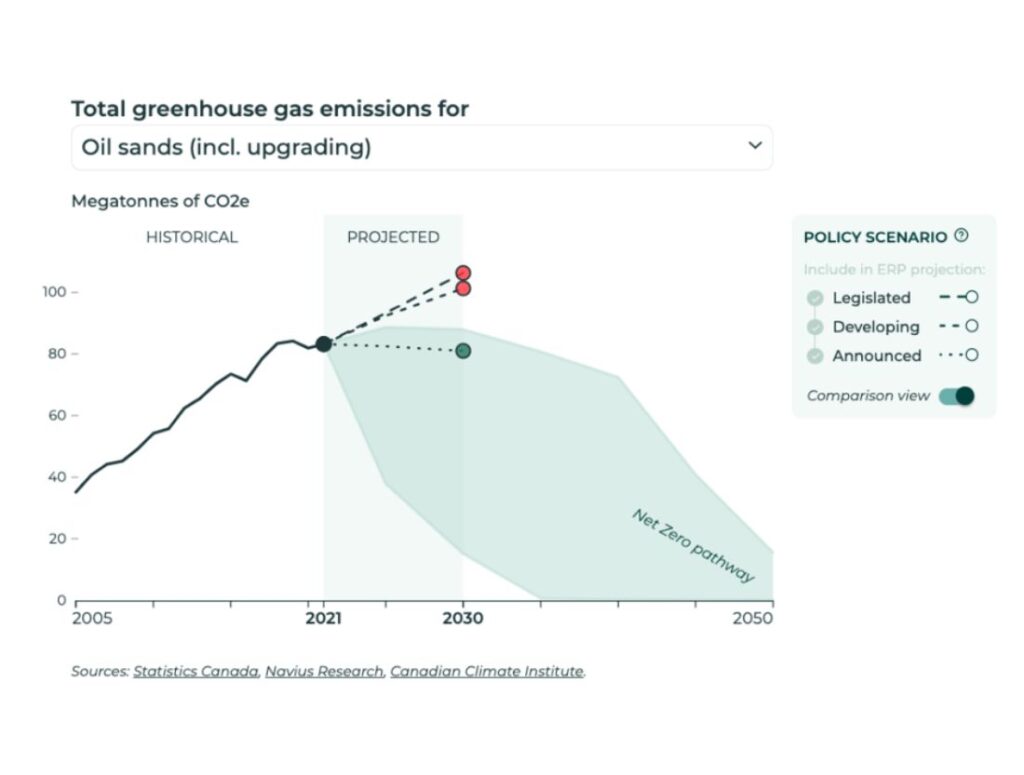

Analysis from the Canadian Climate Institute’s new 440 Megatonnes project shows that the oil and gas sector is out of sync with its net zero pathway under existing policies. Further expansion in the sector would worsen the problem—locking in even more emissions. Additionally, it would force other sectors to make up the difference and perpetuate a status quo that makes other sectors, namely transportation, harder to decarbonize.

Figure 1: Oil sands projected emissions trajectory (Scope 1 and 2) relative to a net zero pathway

At minimum, that raises the cost of the energy transition. At worst, it puts Canada’s climate goals out of reach altogether.

Carbon lock-in also has important global implications, given that Canada’s emissions targets for the oil and gas sector only consider Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Downstream Scope 3 emissions associated with consuming exported Canadian fossil fuels can represent more than 75% of lifecycle emissions. And since Canada exports about 80% of its oil and 40% of its natural gas, the vast majority of the sector’s emissions are not captured by Canada’s emissions inventory.

Putting a cap on it

A new approach being proposed by the federal government offers an answer to this challenging problem: a cap on oil and gas emissions.

By setting an explicit limit on the sector’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions that declines over time, the cap directly addresses the global market and policy uncertainty that is leading the sector to consider expansion. As long as the cap restricts the use of offsets and other flexibility mechanisms, it would preclude the construction of emissions-intensive new assets and facility upgrades that would be out of step with Canada’s emissions reduction goals.

Overall, 440 Megatonnes’ analysis not only shows that a well-designed cap will be necessary for the sector to be in alignment with a least-cost net zero pathway, but it can also support the transformation of the sector into low-carbon business products that are financially viable in the long run. These new business lines would skirt the concerns with lock-in and also help smooth the transition for workers in the oil and gas sector.

Taking a better path

As Canada works toward the goal of net zero by 2050, bending the curve on emissions from existing oil and gas assets is already a considerable challenge. Building new assets or upgrading facilities that extend their lifespan risks locking in even more emissions that makes it harder (or impossible) to achieve net zero.

But there’s a better path.

By implementing a cap on oil and gas emissions, Canada will be able to better address global market and policy uncertainty that exacerbates carbon lock-in while ensuring that oil and gas emissions are aligned with Canada’s climate goals.