Climate change, primarily from the burning of fossil fuels, is causing more frequent and intense heat waves (ClimateData.ca 2024). These heat waves are threatening the safety, well-being, and prosperity of Canadians—even in cities that have historically had more moderate climates, such as Vancouver, Whitehorse, and Halifax.

Globally, 2024 was the hottest year on record, and the past ten years were the ten warmest years on record (World Meteorological Organization 2025). Canada, which is warming faster than anywhere else on earth, is suffering the consequences of the overheating climate (McBean 2024).

Climate change fuels heat waves

- Climate change increases the frequency of extreme heat, and makes heat waves hotter, longer, and more widespread (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2025; Borenstein 2024; Hagemann 2018).

- Canada is warming twice as fast as the global average, and Canada’s Arctic is warming nearly four times as fast (Government of Canada 2019; Rantanen et al. 2022).

- Climate projections show that by the second half of this century, many Canadian cities will see at least four times as many +30°C days per year on average compared to historical data (Climate Atlas of Canada n.d.).

- The June 2024 heat wave that struck central and Eastern Canada was two to 10 times more likely due to climate change, with temperatures over 10 degrees higher than normal in parts of Quebec and Atlantic Canada (Shingler 2024).

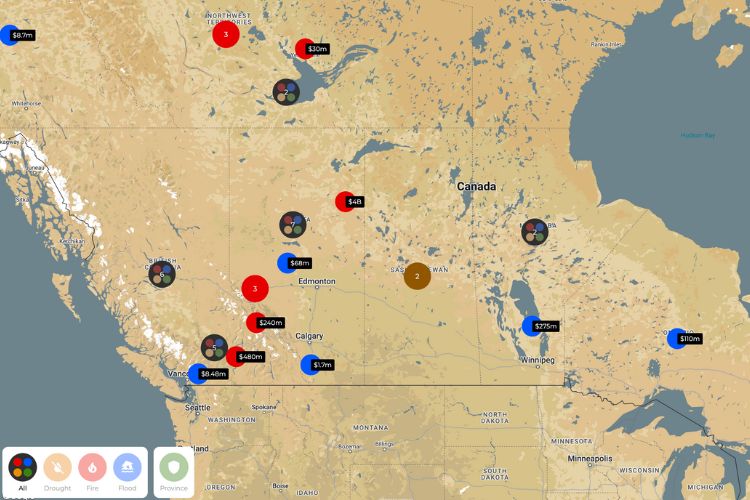

Explore the climate costs tracker to visualize climate-fuelled weather events in Canada.

Climate-fuelled heat makes wildfires worse

- Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions (high temperatures, low humidity, and drought conditions) in Eastern Canada in 2023, and made Québec’s season 50 per cent more intense (World Weather Attribution 2023).

- Heat waves make it easier for wildfires to start and spread by increasing the likelihood of lightning strikes, the primary cause of wildfires (Pérez-Invernón et al. 2023). They also dry out vegetation, making it more flammable (Natural Resources Canada 2024).

- During the 2021 heat wave in B.C., the number of active wildfires rose from six to 175, consuming nearly 79,000 hectares, including the entire town of Lytton (White et al. 2023).

- For more information on climate change and wildfires, please see our wildfires fact sheet.

Climate-fuelled extreme heat is causing rising death rates and health issues across Canada

- A study in Nature found that between 1981 and 2018, 37 per cent of heat-related deaths globally were attributable to climate change (Vicedo-Cabrera et al. 2021). This increased mortality is evident on every continent.

- Health risks from extreme heat include cardiovascular events, respiratory conditions, kidney disease, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and mental health impacts such as increased anxiety, depression, and aggressive behavior (Bell et. al 2024).

- Elevated death rates have been documented during and following heat waves in Canada (Government of Canada 2024). The 2021 heat wave caused an estimated 619 heat-related deaths, making it the deadliest disaster in B.C.’s recorded history (BC Coroners Service 2022).

- Our research shows that without action on adaptation and health system preparation, B.C. could average 1,370 heat-related deaths per year by 2030 (Beugin et al. 2023).

- Scientists found that the 2021 B.C. heat wave would have been virtually impossible without human-caused climate change (Philip et al. 2022).

- A 2024 study concluded that elevated summer temperatures in Québec are linked to 470 deaths, 225 hospitalizations, 36,000 emergency room visits, 7,200 ambulance transports, and 15,000 calls to Info-Santé every year.

- With climate change, the number of heat-related illnesses and deaths could double or even quadruple in the province by 2050 (Boudreault et al. 2024).

The economic burden of climate-fuelled extreme heat is growing

- Our 2021 report The Health Costs of Climate Change projected that the costs of heat-related deaths and reduced quality of life from extreme heat in Canada would range from $3 billion to $3.9 billion per year by mid-century (Clark et al. 2021).

- Our analysis shows that the 2021 heat wave in B.C. caused $12 million in additional healthcare costs, and that the societal costs from premature deaths were $5.5 billion (Beugin et al., 2023).

- Canada’s manufacturing sector alone could see annual losses of $1-2 billion by 2050, due to the productivity impacts of heat waves on the workforce (Clark et al. 2021).

- Our 2021 report Under Water: The Costs of Climate Change for Canada’s Infrastructure estimated that by mid-century, annual heat-driven damage to roads and railways could increase by over $5 billion and damage to electricity infrastructure could increase by over $1 billion (Ness et al., 2021).

Governments can act to protect communities and slow further warming

- Scientists have warned that the consequences of climate change will only get worse as the concentration of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere increases (IPCC 2022).

- Governments must act immediately to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming, while adapting and preparing for the health and safety risks from extreme heat.

- Adaptation strategies can improve outcomes for the most vulnerable populations, including the elderly, children, people with chronic illness, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups (Health Canada 2011).

- Effective adaptation strategies include:

- Installing indoor cooling devices like heat pumps or air conditioning, and planting green roofs and trees for shade. Our analysis shows these could reduce heat-related deaths and hospitalization 12 per cent and 7 per cent, respectively, in B.C. by the 2030s (Beugin et al. 2023).

- Providing employers and the public with information on how to stay safe during extreme heat waves.

- Sending early heat warnings to allow people, communities and responders to prepare.

- Designing infrastructure to withstand extreme heat and rainfall, potentially reducing damage costs by 80 per cent by the end of the century, or up to $3.1 billion each year (Ness et al. 2021).

- Regulating maximum indoor temperatures in rental housing to protect tenants from extreme heat (Lawton 2025).

Resources

- Reporting Extreme Weather and Climate Change: A Guide for Journalists (Clarke and Otto 2024)

- Climate Change and Heatwaves (World Meteorological Organization, 2023)

- Extreme Heat Events Overview (Government of Canada 2024)

- Extreme Heat Preparedness Guide (PreparedBC 2024)

- Health Impacts of Extreme Heat (Climate Atlas of Canada 2024)

Experts available for comment and background information on this topic:

- Ryan Ness is Director of Adaptation research at the Canadian Climate Institute and the lead researcher on the Institute’s Cost of Climate Change series. Ryan est également disponible pour des entretiens en français. (Eastern Time, English and French).

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact:

Claudine Brulé

Communications and Media Relations Specialist

cbrule@climateinstitute.ca

(514) 358-8525

References

BC Coroners Service. 2022. Extreme Heat and Human Mortality: A Review of Heat-Related Deaths in B.C. in Summer 2021. June 7. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/death-review-panel/extreme_heat_death_review_panel_report.pdf

Bell, Michelle L., Antonio Gasparrini, and Georges C. Benjamin. 2024. “Climate Change, Extreme Heat, and Health” eds. Caren G. Solomon and Renee N. Salas. New England Journal of Medicine 390(19): 1793–1801. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2210769.

Beugin, Dale, Dylan Clark, Sarah Miller, Ryan Ness, Ricardo Pelai, and Janna Wale. 2023. The case for adapting to extreme heat: Costs of the 2021 B.C. heat wave. Canadian Climate Institute. https://climateinstitute.ca/reports/extreme-heat-in-canada/

Borenstein, Seth. 2024. “Study says since 1979 climate change has made heat waves last longer, spike hotter, hurt more people.” Associated Press, March 29. https://apnews.com/article/heat-wave-climate-change-worsen-hotter-797aae046df8165f5f8be7d3f40a8b74

Boudreault, Jérémie, Éric Lavigne, Céline Campagna, and Fateh Chebana. 2024. “Estimating the heat-related mortality and morbidity burden in the province of Quebec, Canada.” Environmental Research, September 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119347

Bratu, Andreea, Kiffer G. Card, Kalysha Closson, Niloufar Aran, Carly Marshall, Susan Clayton, Maya K. Gislason, Hasina Samji, Gina Martin, Melissa Lem, Carmen H. Logie, Tim K. Takaro, and Robert S. Hogg. 2022. “The 2021 Western North American heat dome increased climate change anxiety among British Columbians: Results from a natural experiment.” The Journal of Climate Change and Health, May. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667278222000050

Clark, Dylan, Ryan Ness, Dena Coffman, and Dale Beugin. 2021. The Health Costs of Climate Change: How Canada Can Adapt, Prepare, and Save Lives. Canadian Climate Institute. https://climateinstitute.ca/reports/the-health-costs-of-climate-change/

Clarke, Ben, and Friederike Otto. 2024. “Reporting extreme weather and climate change: A guide of journalists.” World Weather Attribution. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/reporting-extreme-weather-and-climate-change-a-guide-for-journalists/

Climate Atlas of Canada. (n.d.) Urban Heat Island Effect. Prairie Climate Centre. https://climateatlas.ca/urban-heat-island-effect

Climate Atlas of Canada. 2024. “Heath impacts of extreme heat.” https://climateatlas.ca/health-impacts-extreme-heat

ClimateData.ca. 2024. “Heat waves and climate change.” https://climatedata.ca/resource/heat-waves-and-climate-change/

Communicating the Health Risks of Extreme Heat Events: Toolkit for Public Health and Emergency Management Officials. 2011. Ottawa, Ontario: Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/climate-change-health/communicating-health-risks-extreme-heat-events-toolkit-public-health-emergency-management-officials-health-canada-2011.html

Environment and Climate Change Canada (2025) Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Extreme heat events. Consulted on Month day, year. Available at: www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/extreme-heatevents.html

Government of Canada. 2019. “Canada’s climate is warming twice as fast as global average.” Press release. April 2. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2019/04/canadas-climate-is-warming-twice-as-fast-as-global-average.html

Government of Canada. 2024. “Extreme heat events: Overview.” May 7. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/climate-change-health/extreme-heat.html

Hagemann, Hannah. 2018. “Northern Hemisphere Heat Waves Covering More Area than Before.” https://blogs.agu.org/geospace/2018/12/20/northern-hemisphere-heat-waves-covering-more-area-than-before/.

Henderson, Sarah B., Kathleen E. McLean, Michael J. Lee, and Tom Kosatsky. 2021. “Extreme heat events are public health emergencies.” BC Medical Journal, November.

International Labour Organization. 2024. Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate. April 22. https://www.ilo.org/publications/ensuring-safety-and-health-work-changing-climate

IPCC, 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Kirchmeier-Young, Megan, N. P. Gillett, F. W. Zwiers, A. J. Cannon, and F. S. Anslow. 2019. “Attribution of the influence of human-induced climate change on an extreme fire season.” Earth’s Future, January. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF001050

Lawton, Betsy. 2025. “Home Cooling Policies Can Combat Health Impacts of Extreme Heat, But Should Be Paired with Strategies to Reduce Unintended Consequences.” https://www.networkforphl.org/news-insights/home-cooling-policies-can-combat-health-impacts-of-extreme-heat-but-should-be-paired-with-strategies-to-reduce-unintended-consequences/.

McBean, Gordon. 2024. “2023 was the hottest year in history — and Canada is warming faster than anywhere else on earth.” The Conversation, January 11. https://theconversation.com/2023-was-the-hottest-year-in-history-and-canada-is-warming-faster-than-anywhere-else-on-earth-220997

Natural Resources Canada. 2024a. “Canada’s record-breaking wildfires in 2023: A fiery wake-up call.” May 21. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/simply-science/canadas-record-breaking-wildfires-2023-fiery-wake-call/25303

Ness, Ryan, Dylan G. Clark, Julien Bourque, Dena Coffman, and Dale Beugin. 2021. Under Water: The Costs of Climate Change for Canada’s Infrastructure. Canadian Climate Institute. https://climateinstitute.ca/reports/under-water/

Parisien, Marc-André, Quinn E. Barber, Mathieu L. Bourbonnais, Lori D. Daniels, Mike D. Flannigan, Robert W. Gray, Kira M. Hoffman, Piyush Jain, Scott L. Stephens, Steve W. Taylor, and Ellen Whitman. 2023. “Abrupt, climate-induced increase in wildfires in British Columbia since the mid-2000s.” Communications Earth & Environment, September 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00977-1

Pérez-Invernón, F.J., F.J. Gordillo-Vázquez, H. Huntrieser, et al. “Variation of lightning-ignited wildfire patterns under climate change.” Nature Communications 14, 739 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36500-5

Philip, Sjoukje Y., Sarah F. Kew, Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, et al. 2022. “Rapid attribution analysis of the extraordinary heat wave on the Pacific coast of the US and Canada in June 2021.” Earth System Dynamics, December 8. https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/13/1689/2022/

PreparedBC. 2024. “Extreme heat preparedness guide.” Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/public-safety-and-emergency-services/emergency-preparedness-response-recovery/embc/preparedbc/preparedbc-guides/preparedbc_extreme_heat_guide.pdf

Rantanen, Mika, Alexey Yu. Karpechko, Antti Lipponen, et al. 2022. “The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979.” Commun Earth Environ 3, 168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3

Shingler, Benjamin. 2024. “Canada draws link between June heat wave and climate change with new attribution analysis.” CBC, July 9. https://www.cbc.ca/news/climate/canada-eccc-rapid-attribution-heat-1.7257456

Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M., N. Scovronick, F. Sera, et al. 2021. “The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change.” Nature Climate Change, May 31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x

White, Rachel H., Sam Anderson, et al. 2023. “The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021.” Nature Communications, February 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36289-3

World Meteorological Organization. 2023. “Climate change and heatwaves.” September 21. https://wmo.int/content/climate-change-and-heatwaves

World Meteorological Organization. 2025. “WMO confirms 2024 as warmest year on record at about 1.55°C above pre-industrial level” January 10. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-confirms-2024-warmest-year-record-about-155degc-above-pre-industrial-level

World Weather Attribution. 2023. “Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada.” August 22. https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-more-than-doubled-the-likelihood-of-extreme-fire-weather-conditions-in-eastern-canada/