The federal government rightfully sees building major projects in energy, transportation, and natural resources as drivers of clean growth, Canadian competitiveness, and long-term prosperity. At the same time, it has also prioritized fiscal discipline.

Blended finance can help reconcile those two goals.

What is blended finance? It’s a model of financing that strategically uses public funds to reduce project risks and encourage private investment.

The Canadian government has already begun to wield blended finance tools. Yet those tools are not necessarily combining to form a co-ordinated strategy.

In this post, we identify three recommendations for the federal government to strategically and coherently scale up blended finance as a powerful tool for mobilizing private capital for major clean growth projects. For a government with both an ambitious agenda to build and great expertise in capital markets, turning to blended finance is a natural solution to making big investments with fiscal restraint.

What is blended finance?

Despite their big economic benefits for society, major infrastructure and industrial projects come with market risks. Investors may be hesitant given the large capital expenditures, complex risks, and long payback periods that typically come with major greenfield projects.

At the same time, public finance—i.e., government spending—only goes so far. Fiscal constraints can limit governments’ ability to step in with extensive public investments.

Blended finance is a funding model that leverages the heft of both the private and public sector. It’s where governments—or government agencies—accelerate the development of projects in the public interest by creating a finance structure that crowds in private investors. Blended finance tools re-allocate some of the project risks from private investors to the government, which can afford to be more risk tolerant due to large balance sheets and/or lower borrowing costs. This risk-sharing approach can catalyze relatively small amounts of public funds into significantly larger private investments and make it possible for the project to go ahead.

In essence, blended finance uses governments’ capacity to absorb early-stage and long-term project risks, while private capital brings the scale, efficiency, and expertise necessary to deliver a project.

Blended finance tools come in many forms, including concessional loans, equity co-investment, first-loss guarantees, technical assistance facilities, or results-based financing. The government agency and project proponents typically negotiate which tool is most suitable for individual projects, which will depend on specific funding needs and risk profile.

The use case for blended finance in Canada

Blended finance works well when two conditions are met.

First, blended finance (and public funding more generally) should support projects that generate positive public benefits, such as emissions reductions, reconciliation for Indigenous Peoples, or energy security. If private investors are unable to monetize these positive impacts on society, a project’s risk-return ratio may not be quite attractive enough for private capital—even if its development would be a net win for society. Blended finance is one way for governments to address this failure in the market. The more significant the market failure, that is the difference between public and private returns, the more reason there is for governments to assume project risks in blended finance deals.

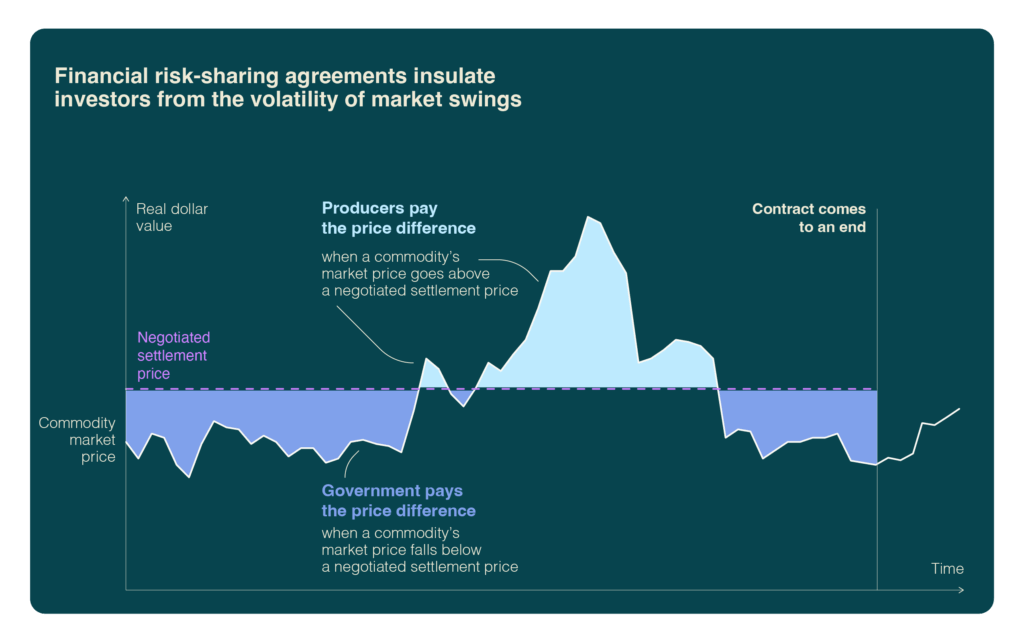

For example, development of a critical minerals mine may have significant strategic value for Canada’s economy in terms of energy security and trade diplomacy, while private investors may be deterred by high price volatility in the global market for these resources. Government agencies may decide to share some of these market risks and thus enable the project to go ahead (see Figure 1 for an example of how this can work).

Figure 1: Financial risk-sharing agreements can insulate investors from the volatility of market swings

Second, blended finance is useful for supporting projects that will eventually deliver a financial return. In contrast to other public investment tools such as grants, subsidies, and tax incentives, government agencies providing blended finance typically recoup their initial investment on a portfolio basis and may participate in positive returns. This feature helps keep costs down for taxpayers, and can even generate new revenues.

Canadian governments have established multiple agencies with a mandate to use blended finance for projects that meet these criteria. For example, the federal government created the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) to apply blended finance to fund big infrastructure projects in partnership with private investors. These projects serve Canadian communities but fail to secure private capital due to high risks or long payback periods. Similarly, the mandate of the Canada Growth Fund (CGF) is to use instruments such as equity investments, off-take agreements, and debt below market rates to catalyze private investment in projects that help meet the country’s climate objectives but that also face elevated demand, policy, regulatory, and execution risks.

Federal and provincial Indigenous loan guarantee programs are further examples of blended finance. These programs can help drive reconciliation and Indigenous self-determination by improving Indigenous Nations’ access to capital (limited by the legacy of colonialism) through equity ownership in major projects. Through these programs Indigenous investors are able to borrow at lower rates because they benefit from the high credit rating of the Canadian government, their guarantor.

A potential challenge with scaling up blended finance is that transaction costs of individual deals are typically high. Each signed agreement usually requires extensive due diligence to ensure the project meets the two conditions outlined above and bespoke structuring of the investment to land the right level of concessionality. In other words, the government agency should take on just enough risk to make the project attractive to private investors—but not so much risk that it crowds out private capital. There might be opportunities for developing more standardized solutions, including carbon contracts for difference, financing approaches for similar projects (e.g. building retrofits), or formalizing partnerships with other finance organizations. Importantly, a strategic, co-ordinated approach to scaling up blended finance will help minimize transaction costs by preventing duplication with other public funding programs, limiting competition among blended finance agencies, and strengthening industrial carbon markets.

How to scale up blended finance in Canada efficiently

If Canada is to systemically scale up blended finance to maximize its potential in the economy’s clean growth agenda, the federal government should implement three crucial actions that will help grow the sector in a strategic and co-ordinated fashion.

- Maximize efficiency by making new blended finance programs complementary with other funding programs

Future blended finance deals should align and complement all the other financial incentives offered by the government. As a new paper by C.D. Howe Institute explains, over 20 government departments and agencies are tasked with administering the $180 billion committed by the federal government for advancing major infrastructure projects, primarily using grants and subsidies. Many provinces also have their own specific programs and funds that overlap with these federal initiatives.

This complexity requires a strategic vision and consistent guidance on when to use blended finance for project support as opposed to other public investment tools. Avoiding duplication and maximizing co-ordination to ensure that the projects that meet the two conditions outlined above have access to blended finance is paramount to effectively and efficiently delivering a new round of major project financing. - Bring more clarity, guidance, and transparency to a confusing blended finance landscape

Looking at the existing blended finance portfolio in Canada, there is currently little clarity and guidance on how project proponents should approach the various agencies for support. Right now, project proponents can approach multiple government agencies and programs in parallel to strike a bespoke deal. Given that each government agency has its own mandate or target to meet, and given that each business has an incentive to maximize the level of public support, it could result in government agencies outcompeting each other on the same deal. And while this may be good for the proponent, it’s bad for taxpayers. Competition between different agencies may lead to less transparency and drive up transaction costs for individual deals, putting scalability of blended finance at risk.

What could help here is a new approach to pairing blended finance agencies with projects. Each government agency has its own mandates and a different risk tolerance for doing deals, and this is intentional. Some agencies, like the CGF, are geared to support projects that are earlier in their journey toward commercialization and need scale. The CIB, on the other hand, is geared to target much larger projects and typically those that rely on more mature (i.e., less risky) technologies.

Governments can take concrete steps to improve clarity and efficiency for both project proponents and funding agencies. That can include mapping the current blended finance ecosystem with a clear delineation of agencies’ mandates to identify any overlap, the degrees of concessionality these agencies provide (namely, the degree to which they offer below market rates), and their risk appetite. Other steps could include the establishment of a central co-ordinating body directing project proponents, or mandates for greater communication and collaboration between the various agencies.

- Maximize compatibility with a robust industrial carbon market, Canada’s most effective policy for cutting emissions

The country’s large-emitter trading systems (LETS) provide a powerful incentive for companies to make major investments in reducing emissions. And when combined with blended finance models, these tools can dramatically improve the financial return of a project, both for the proponent and for taxpayers.

For example, the CGF invested $500 million in the Strathcona carbon capture and sequestration project in 2024, where CGF’s return is tied to the carbon credits generated by the project. This effectively means that the value of the project—to both CGF and Strathcona—hinges on a robust and liquid carbon market.

Modernizing and strengthening LETS makes blended finance work better for the Canadian economy. Higher and more predictable credit prices will reduce the need for blended finance—and thereby public risk exposure—in the first place and bolster investors’ confidence in leveraging this income stream in blended finance deals as demonstrated in the Strathcona example. Again, the result is more private capital investment with less risk for the Canadian public. Even Canada’s scaled-up blended finance portfolio cannot—and should not—replace the strong investment signals coming from industrial carbon pricing, but rather, Canadian governments should strengthen both instruments to achieve maximal impact on investment and emissions.

Canada can take blended finance to the next level

The task facing Canada is clear: scale major projects that drive economic growth as well as emissions reductions, while minimizing the burden on public budgets. Blended finance can help Canada deliver.

Building on Canada’s growing experience with blended finance deals, what’s required now is scale, coordination, and strategic direction. Governments must move from assessing potential projects in parallel to a more filtered and strategic approach. They must also ensure that Canada’s carbon markets are strong to establish carbon trading as an income revenue to leverage in innovative blended finance deals.

If implemented well, blended finance can be a powerful tool for unlocking the private capital required for achieving the government’s economic goals while also maintaining fiscal discipline. Realizing this potential requires upfront investment in a strategic vision, practical guidance, and increased collaboration between governments, the funding agencies, and project proponents.