British Columbia’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard is among the province’s most effective policies for reducing emissions, but it often flies under the radar. It has reduced British Columbia’s annual greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector by an average of six per cent per year between 2010 and 2020 and is expected to drive 31 per cent of British Columbia’s 2030 greenhouse gas reduction targets. It is also a model for the long-anticipated federal Clean Fuel Standard.

Two proposed changes to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard this fall could make the regulation even stronger and create an opportunity for British Columbia to become a global leader in a new green technology. Realizing these potential benefits, however, means getting the details right.

Two changes under consideration

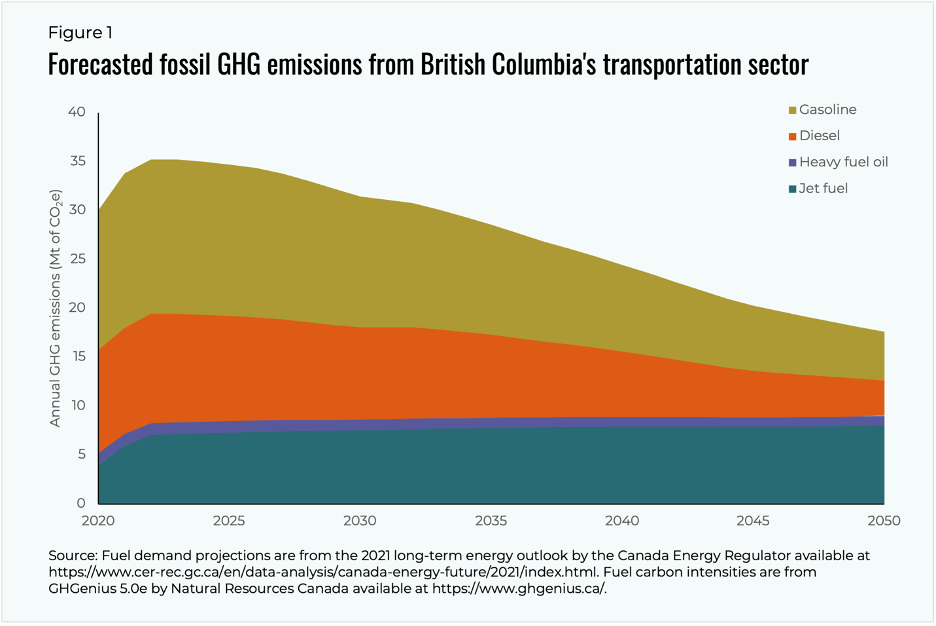

The first big proposed change to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard is to expand it to include jet fuel and marine fuel—it currently only covers diesel and gasoline. These additions would allow suppliers of low-carbon jet and marine fuel to generate and trade Low Carbon Fuel Standard credits while tightening carbon intensity requirements for suppliers of fossil fuels. Fossil jet and marine fuels are estimated to account for 51 per cent of British Columbia’s transportation greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (see Figure 1).

The second big proposed change is to allow the use of direct air capture with permanent storage to generate compliance credits. This technology enables permanent removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, resulting in negative emissions. This is key to achieving global net zero targets. If commercialized, this new technology could make British Columbia a global leader.

Taken together, these proposed changes create opportunities to make the Low Carbon Fuel Standard even more effective in reducing British Columbia’s greenhouse gas emissions than it already is. The first change could provide a big boost in demand for low-carbon alternatives in two previously uncovered fuel categories. Demand for additional compliance credits would push up credit prices (for all fuel categories). At the same time, expanding the low-carbon liquid fuels market could induce lower credit price volatility. Both results would improve the business case for investing in low-carbon fuel projects.

The second change will not only contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions but position the province as a leader in direct air capture and sequestration technology. British Columibia would provide an example to other provinces of how to fill the policy gap that exists around investing in negative emissions technologies such as direct air capture. To date, it is still considered a “wild card”—a riskier technology.

Capturing these opportunities, however, is not guaranteed. It depends on how the changes to the regulation are ultimately designed. To take advantage of these opportunities, the provincial government should consider three important shifts—outlined below–as it reforms this critical regulation.

Three ways to get the details right

1. Close the incentive gap for aviation and marine fuel

There is an existing incentive gap that favours renewable diesel over low-carbon jet fuel production. This gap should be closed in the revamped Low Carbon Fuel Standard. Jet fuel’s energy density and benchmark carbon intensity are generally lower than those of diesel. The difference leads to low-carbon jet fuel generating fewer credits than renewable diesel, meaning there is less economic reward to offset fossil jet fuel compared to renewable diesel, even if they are produced via the same process and have the same carbon intensity. With both fuels competing for feedstocks, lower credit revenue added to higher production cost has tipped the balance in favour of renewable diesel.

A similar gap could occur for low-carbon marine fuel if there are differences in energy density and benchmark carbon intensities with competing alternatives from other fuel categories.

Fortunately, British Columbia has several implementation options that could level the playing field. These include setting more gradual carbon intensity reductions for jet and marine fuel or incorporating the added benefits of low-carbon alternatives into carbon intensity scores, such as reduced contrail and black carbon impacts of low-carbon jet fuel. Tweaks like these could help shrink the incentive gap, and ensure that the changes to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard lead to meaningful increases in low-carbon jet and marine fuel supply.

2. Include indirect land-use change in carbon footprint measurements to increase the incentive for less-developed advanced clean fuels

The proposed overhaul to British Columbia’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard currently has no plans to address an issue that has challenged clean fuel regulations over the years: excluding indirect land-use change (ILUC) emissions when calculating the carbon footprint of fuels. The exclusion is particularly meaningful for advanced biofuel pathways for jet fuels, for instance, that use emerging feedstocks but don’t have their carbon-sequestering land use impacts monetized.

Advanced biofuels are integral to long-term decarbonization, but the industry is still struggling to get them off the ground. Excluding ILUC emissions from carbon footprint calculations deters development of the less carbon-intensive advanced biofuels as it ignores the emissions released by traditional biofuels due to competition for arable land. In some cases the carbon footprint calculations also exclude carbon sequestration benefits (e.g. from energy crops feedstocks) that could lower carbon intensity scores and provide additional revenue to producers.

Setting standards to quantify ILUC emissions is complex and challenging, but guidance can be drawn from organizations that have a head start. For instance, the International Civil Aviation Organization developed regional ILUC values for various renewable jet fuel feedstocks for use in its carbon offsetting scheme. Experiences in California and Oregon can also offer inspiration on how to estimate ILUC values.

3. Expand the geographic boundaries of direct air capture to accelerate deployment

While fewer details are known on the province’s plan to include direct air capture with permanent storage in the changes to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, limiting eligible projects to those located within British Columbia—as has been proposed—could slow down the progress of technology development. Although it makes sense that credit support goes to projects impacting the province’s greenhouse gas inventory, the stipulation ignores a key factor behind the regulation’s success so far: enabling solutions to come from places where they can be produced more cost-effectively. For instance, 30 per cent of all compliance credits from the regulation in 2019 were generated by renewable diesel imported from countries like Singapore and the Netherlands.

British Columbia has an advantage in direct air capture and sequestration, as it is home to a company that is leading the way in this new technology. However, a key to its success is accelerating deployment at scale, and restricting support to projects located within the province could result in missed opportunities to quickly scale the technology and bring its costs down. Places like Alberta or Saskatchewan have deep carbon sequestration expertise and much larger carbon storage potential relative to British Columbia. The province may consider taking a similar approach to California and expand project eligibility for direct air capture credits to locations beyond its boundaries. To avoid the issue of double counting emissions reductions, British Columbia should also consider guidelines about how to claim and report negative emissions captured outside the province.

Clean fuel liftoff

British Columbia’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard has been instrumental in driving down the province’s transportation emissions, particularly as it has provided important policy leadership both in Canada and abroad. Building on its pioneering role, the province now has an opportunity to take this policy to the next level, implementing solutions for hard-to-abate sectors like aviation and shipping and negative-emissions technologies.

Realizing the full potential of those solutions in the next Low Carbon Fuel Standard iteration will be a challenge, but the ideas outlined above could help to meet that challenge, as long as the province takes care to get the details right.