The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act has sparked concerns about the competitiveness of Canada’s upstream oil sector in the low-carbon energy transition. The claim by industry is that new U.S. incentives will drive capital in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies south of the border.

New analysis, however, shows that when all the incentives from governments are tallied up, when it comes to CCUS in the upstream oil sector the Canadian carrots are already sweet enough.

Is CCUS competing for capital with the U.S.?

Reaching Canada’s net zero goal requires emissions reductions in the short term from upstream oil production. Several different technologies will play a role in this transformation, but industry and governments have identified CCUS as having significant potential.

Successfully scaling up CCUS in upstream oil production requires an injection of new investment. To help mobilize private capital and get projects off the ground, North American governments have stepped in to help.

Canada already offers incentives to deploy CCUS, along with a set of newly announced incentives. Industry is calling for more, claiming that new measures under the Inflation Reduction Act will result in CCUS investments flowing south, making it harder and more expensive for Canada’s industry to meet their climate commitments.

But our analysis shows those claims are unfounded.

No more carrots are needed for CCUS in Canadian oil sands

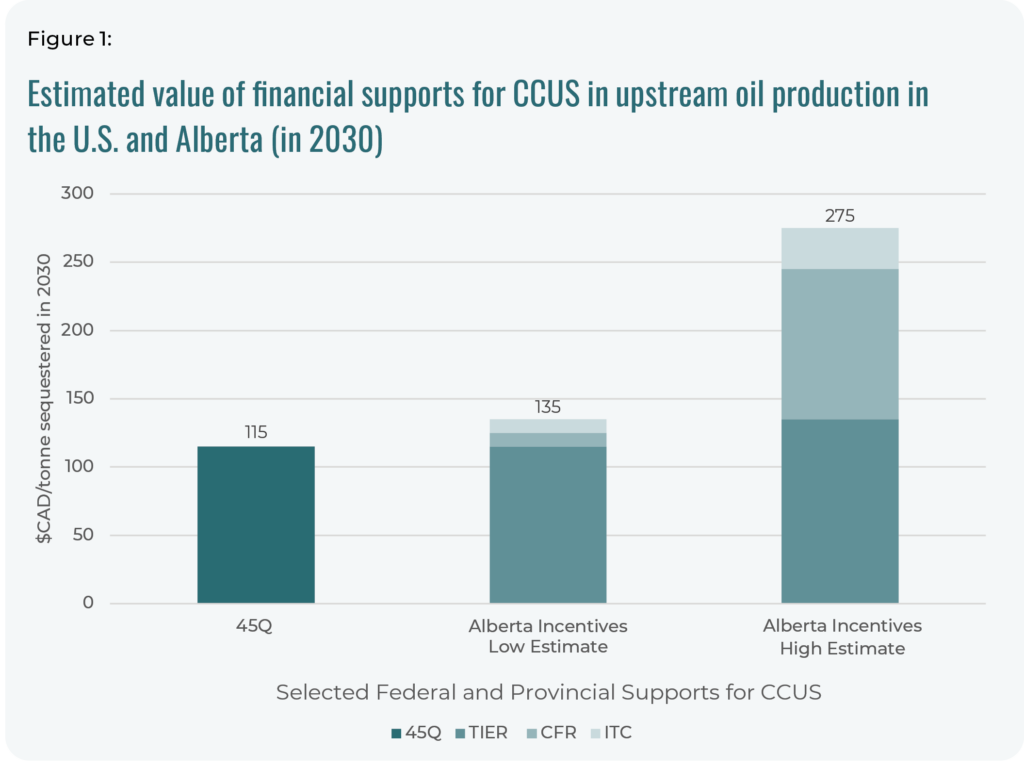

When all the regulations and incentives offered by Canadian governments for CCUS in upstream oil are added together (see the figure below), they amount to more than those offered in the U.S.

Our analysis looks specifically at the biggest oil-producing jurisdictions in each country: Alberta and Texas. The incentives in Texas are primarily directed through the 45Q tax credit, which offers about C$115 for every tonne that U.S. projects can sequester. This incentive has been available since 2008—the Inflation Reduction Act expanded and extended it.

In Alberta, where the vast majority of announced CCUS projects in Canada are located, credits from the Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction (TIER) regulation system, combined with incentives from the announced federal Investment Tax Credit and Clean Fuel Regulations, will exceed the 45Q credit in 2030 with a value of at least C$135/tonne, even using conservative assumptions. In a high-estimate scenario, the total value of support in Canada could reach as high as $275/tonne—more than double the support offered in the U.S.

While there is still some uncertainty about the exact value of public support in Canada—which is not insignificant as companies gear up to make large investments—there are readily available tools governments can use to address this issue. To improve certainty around TIER credit prices and the revenue generated from capturing and sequestering carbon emissions, governments can tighten up the credit market to prevent an oversupply. To ensure carbon prices are predictable over time, governments can use contracts for differences that lock-in carbon prices.

Canadian oil sands don’t compete directly with U.S. producers for capital

The potential for cross-border competition for capital is also limited by the different resource and emissions profiles in each country. In the U.S., about 75 per cent of total emissions from onshore production are generated through venting, flaring, and fugitive methane emissions (compared to 12 per cent in Canada’s oil sands). Upstream oil production in the U.S. is also more distributed, with fewer large point sources of emissions. This means that the most cost-effective solutions for reducing upstream emissions in the U.S. will come through reducing methane emissions—not CCUS.

The story is different for upstream oil production in Canada, where the case for deploying CCUS is stronger. The oil sands represent about 65 per cent of Canadian oil production, and a significant portion of oil sands emissions come from concentrated point sources, such as natural gas combustion for in situ projects and hydrogen production for bitumen upgraders.

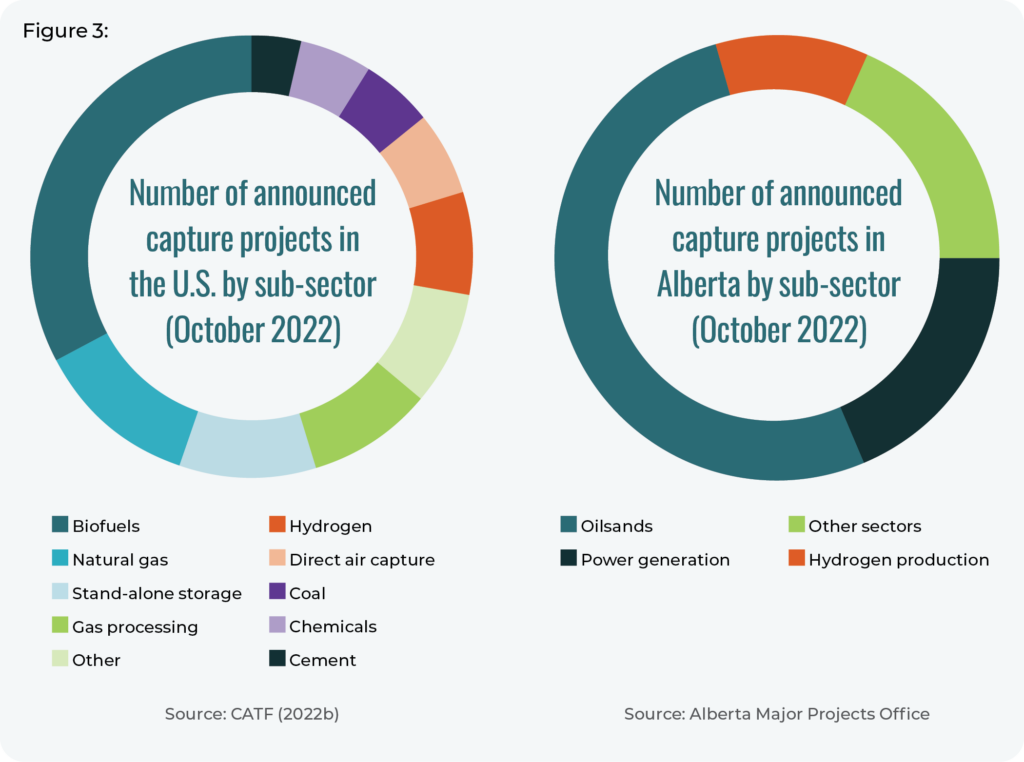

The figure below shows planned CCUS projects in both countries (as of September 2022), illustrating how Canadian upstream oil producers are betting on CCUS far more than those in the U.S. Of the 110 capture projects announced in the U.S., none is associated with upstream onshore oil production. Conversely, of the two dozen CCUS projects announced in Alberta alone, 14 are at oil sands facilities.

Economic competitiveness goes far beyond CCUS subsidies

These findings are part of a bigger conversation about Canada “keeping up” with the Inflation Reduction Act. While cross-border competition is top-of-mind for Canadian industry, subsidies for CCUS come with an opportunity cost.

Spending a public dollar on CCUS in the upstream oil and gas sector could mean spending a dollar less on other important priorities, such as renewable electricity, batteries and storage, or clean fuels.

Governments must therefore balance a wide range of competing investment priorities.

In addition, federal and provincial governments should be careful not to over-subsidize CCUS for the oil and gas sector. Adding more subsidies for the fossil fuel sector, on top of what has already been announced, increases the risk of locking in more emissions and creating stranded assets. Incentives are helpful in mobilizing private capital to drive down the sector’s emissions, but so are regulatory tools, such as carbon pricing and capping the sector’s total emissions.

The question before policy makers is therefore not how policy supports stack up in Canada versus the United States, but whether the right suite of policy supports for CCUS are in place given the specific context of Canada’s upstream oil sector.

Canadian CCUS support is competitive with the U.S.

Maintaining Canada’s competitive edge is critical as the U.S. (and other trading partners) ramp up policies to attract and mobilize private investment. Yet for Canada’s upstream oil sector, comparisons between incentives in the U.S. versus Canada have failed to consider important differences in policy and decarbonization pathways.

Canadian climate policies are layered compared to the U.S., which relies almost entirely on subsidies to encourage CCUS. And while Canada’s investment tax credit for CCUS and contracts for difference policies have yet to be finalized, the new analysis suggests that the Canadian suite of supports—a mix of regulations and subsidies—for upstream oil and gas CCUS will exceed those provided in the U.S. Moving forward, governments should focus on optimizing these policies to reduce uncertainty around the revenues generated from capturing and sequestering emissions, particularly as design details are shored up in the federal budget later this month.

CCUS will not make financial or logistical sense at every facility (and this is an area the Canadian Climate Institute has identified for future research). But where it does make sense, our new analysis finds that—when it comes to CCUS—the oilsands industry doesn’t need any additional support from Canadian governments.