There was undeniable urgency to the first part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth assessment report released on Monday: Global warming is happening faster than expected and it’s driving extreme weather on every continent.

We see the consequences on a daily basis. Too many people living in Canada are already experiencing first-hand the destruction caused by climate change: floods, fires, heat waves. Canada is warming faster than much of the rest of the world: an average of 1.7 degrees increase since 1948. We need to do so much more to adapt to climate change in order to save costs and lives over the next few decades.

So, yes, there is a lot to feel anxious about between the covers of the new IPCC report.

But that’s not all there is. So often, with climate change, the public discussion takes on a tone that verges on nihilism. But the future is still ours to write. With the backing of the IPCC’s historic scientific report, here are my top five reasons that I’m ending this week feeling some hope:

- The worst impacts of climate change can be avoided.

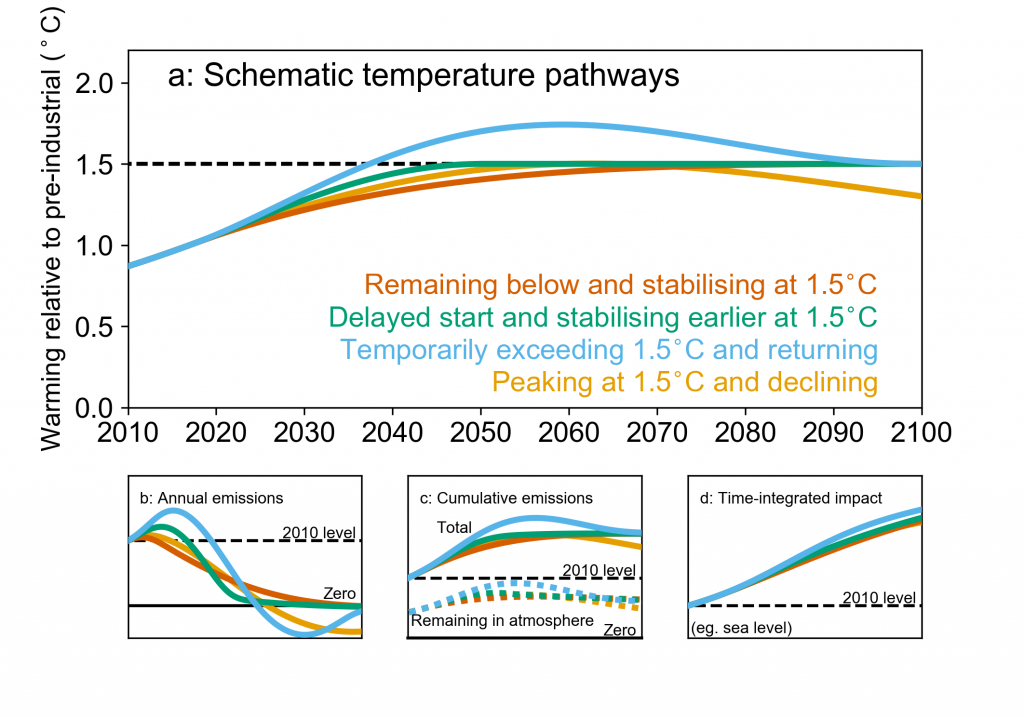

This is the best piece of news: it’s not too late to change course—though we are in a rapidly closing window. Projections in the IPCC report show with a high degree of certainty that if we hit net zero emissions globally by 2050, we could still limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, avoiding catastrophic tipping points. The scientific consensus is clear: the faster we reduce our emissions, the cooler the planet will remain.

- Global warming is reversible—if we act fast.

In the IPCC’s worst-case scenario, global emissions double by 2050, causing temperatures to rise an estimated of 2.4 degrees Celsius between 2041 and 2060. But in the best-case scenario, one in which we reduce emissions quickly over the next decade, the global temperature would rise an estimated 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels between today and 2040, would top out around 1.6 degrees and then begin to fall toward the end of the century.

- Global progress towards reducing emissions is already happening.

Over the past 10 years, clean energy has become cheaper, while climate policies in Canada and abroad have become stronger. Global emissions have slowed, rising only 1 per cent a year over the past decade. We’re still falling short of what was promised in the Paris Agreement, but the very high emissions scenarios predicted in the past are unlikely to come to pass. We’re trending in the right direction, particularly compared to where we were in 2010.

- Carbon doesn’t stick around forever.

Between 65 per cent and 80 per cent of CO2 released into the air dissolves into the ocean over a period of 20 to 200 years. As the IPCC report makes clear, achieving low or very low greenhouse gas emissions will lead, within years, to discernible effects: swiftly reducing emissions today means that global temperature would begin to detectably trend downward within about 20 years.

- Rapidly reducing GHG emissions can be win-win-win.

The IPCC report emphasizes that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will improve air quality, which will save lives in Canada, as well as dollars: the societal health burden from air pollution, currently around $8.3 billion a year in Canada, could fall to $0.7 billion by 2050. And that’s just one example of the benefits. Our report on Canada’s Net Zero Future shows that doing Canada’s part to keep warming to 1.5 is not just achievable, it will be beneficial to our future health and prosperity.

People, as well as climate systems, have tipping points, as the authors of a study called “Plausible grounds for hope” point out. There is every reason to believe we are on the verge of one of those tipping points now: changes made in Canada and globally could help to trigger an acceleration in decarbonization. If the past year and a half of COVID-19 has shown us anything, it’s that we can adapt our behaviour—sometimes very quickly, if not always easily. Let’s get to it.