The Government of Canada currently uses estimates of the “social cost of carbon” to capture the benefits of emissions reductions in its analysis of proposed regulations. But, for several reasons, the estimates used are too low.

Accurately measuring the benefits of climate action is critical to making good decisions. Underestimating benefits means that governments could choose policies that fall short of what the latest science says the world needs to do to avoid the most dangerous and irreversible impacts of climate change. It also means policies could be misaligned with national emission reduction targets, such as the goal to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Luckily, research accumulated over the last decade provides some good ideas for how Canada can improve its social cost of carbon estimates.

Using the social cost of carbon to demonstrate the benefits of climate action

The Canadian federal government has required cost-benefit analysis for all significant federal regulatory proposals since 1999. The idea is to provide decision-makers, such as Cabinet Ministers, with an understanding of potential impacts on the environment, workers, businesses, and consumers. For each new regulation, government departments must demonstrate that benefits exceed costs.

To quantify the benefits of climate action, the government needs to estimate the climate change damages to current and future generations associated with greenhouse gas emissions. The estimated benefit of reducing one tonne of carbon dioxide is called the social cost of carbon (though there are also social costs of other greenhouse gas emissions like methane and nitrous oxides).

Environment and Climate Change Canada began using values to represent the benefits of greenhouse gas emission reductions in its cost benefit analysis in 2010. In 2012, it adopted modified U.S. values that were subsequently updated in 2016.

Why are the social cost of carbon estimates too low?

Estimating the social cost of carbon is not easy. It involves predicting global greenhouse gas emissions far into the future, analyzing climate responses such as temperature increases and flooding, estimating the monetary value of economic, health and environmental impacts of those responses, and determining how society should value those future damages today.

After several decades of research and debate, it is clear that the values the Canadian government uses for the social cost of carbon are too low. Here are some of the reasons why:

- Not all costs of climate change are fully captured, including permafrost thaw, Lyme disease, labour productivity, wildfire, and non-market impacts such as the mental health affects of natural disasters, social unrest, and biodiversity loss.

- The models do not account for the fact that the world’s low-income and poor people could face devastating impacts at relatively low temperature increases.

- Discount rates (where higher rates essentially place a lower value on future costs) may not reflect societal values with respect to protecting future generations.

- Focusing on central values that rise gradually rather than low-probability, high-cost risks may be the wrong risk-management strategy.

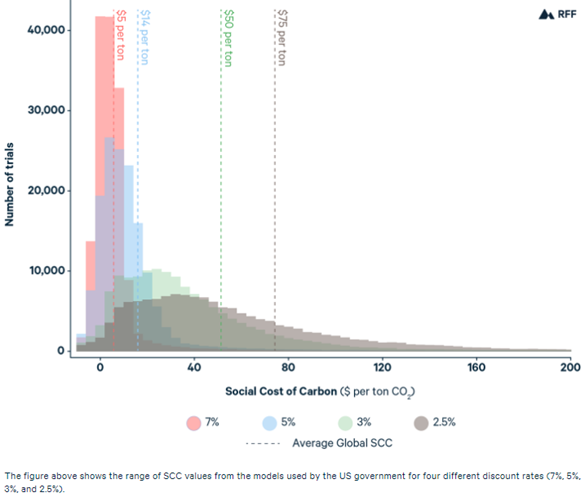

Small changes in discount rates increase social cost of carbon values

Social Cost of Carbon Estimates for the year 2020 (2019 $US per ton of CO2)

(Click to enlarge the graph)

What changes should governments make?

Many of the decisions involved in developing the social cost of carbon are more art than science. This is something that was underlined when the Trump administration drastically lowered U.S. values by raising discount rates and narrowing the scope from global to domestic damages. Discussions on the best values to use therefore need to rise above technical debates.

The Canadian government has generally relied on the expertise of U.S. researchers to update its social cost of carbon estimates. The incoming Biden administration is likely to revise U.S. values to reflect the latest science. Waiting for the U.S., or producing Canadian-led estimates, will take time. This leaves Canadian decision-makers using incomplete information in the interim.

A stop-gap measure could be to use a lower discount rate. Several studies have recommended a lower or declining discount rate for climate policy analysis to capture the global, intergenerational, and long-term nature of climate change. The U.S. used various discount rates to reflect uncertainty in the best value. The lowest discount rate used was 2.5 per cent, slightly lower than the 3 per cent discount rate currently used in Canada. The figure above shows how a small change in discount rate shifts estimated average social cost of carbon values upwards. For the year 2020, the social cost of carbon value would shift upwards by about Cdn$30/tonne.

Canada could also explore the UK approach. Instead of using the social cost of carbon, the UK assesses the cost-effectiveness of policies within the context of meeting its emission targets. Recent research by Kaufman et al. suggests a similar approach for the U.S.. It replaces social cost of carbon values with estimates of near-term CO2 prices consistent with a 2050 net-zero target.

What are the risks of the status quo?

Continuing to use low estimates of the benefits of climate action risks making the wrong policy choices in areas critical to long-term climate objectives. This could in turn result in an inefficient transition, with higher long-term costs if actions are accelerated later to meet targets.

Putting the best information in front of decision makers is essential to good climate policy. While a more comprehensive review is warranted, it is worth considering some near-term tweaks to shine light through the fog of a complex issue.