Published as part of our Indigenous Perspectives series featuring Indigenous-led initiatives to address and respond to climate change.

Introduction

Across Canada, Indigenous leadership is being recognized as an essential component to addressing climate change (CAT, 2021). Much of this is because Indigenous Knowledge and Land1 management practices encompass processes that are known to be effective and sustainable, with 80 per cent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity maintained on Indigenous-managed Lands (Ottenhoff, 2021; Sobrevila, 2008).

Indigenous worldviews offer a different perspective on social resilience to environmental change, one that is based on moral relationships of responsibility that connect humans to animals, plants, and habitats. These responsible practices not only ensure ecosystem goods and services are maintained for future generations, but, more importantly, they centre the moral qualities necessary to carry out these responsibilities: trust, consent, and reciprocity. Moral qualities of responsibility are the foundation that allows us to rely on each other when facing environmental change (Whyte, 2018).

At a time when governments are recognizing their failures in fulfilling obligations to Indigenous Peoples (UBCIC, n.d.), organizations and agencies across jurisdictions must be aware of how Indigenous leadership can be engaged to revive and protect shared environments within urban and peri-urban regions. Climate change threatens the urban natural infrastructure we depend on for a myriad of services, while urbanization encloses more of our natural spaces. Better protection and management of these natural spaces are instrumental to the well-being of humans and non-humans alike.

This case study explores the journey of an Indigenous-led grassroots initiative in the Grand River Territory within southern Ontario, which falls under what has been designated a “crisis ecoregion,” the Lake Erie Lowland (Kraus & Hebb, 2020). Through three stories that describe the fostering of distinct relationships within the Wisahkotewinowak collective (Wisahkotewinowak, 2021a), an urban Indigneous food sovereignty initiative, we illustrate how Indigenous leadership can enhance community efforts to transform our shared social spaces, built environments and ecological climates by:

- finding Land use opportunities in natural urban places;

- imagining and creating place for Land-based learning;

- building and mobilizing community to enhance local biodiversity and social adaptations (Indigenous Climate Hub, 2020); and,

- enhancing Indigenous food sovereignty practices towards community wellbeing.

We argue that these evolving relationships have integrated processes that are fundamental to robust and meaningful climate action, both in terms of centring Indigenous ways of caring for the Land as well as advancing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action through restoring Indigenous Peoples’ relationships to Land and pathways to wellness.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada explicitly calls for actions that close gaps in health equity, including food security (TRC, 2015). Climate change impacts such as heat waves and extreme rain will affect local food systems and security, an important determinant of health, through food accessibility, distribution and food safety (Zeuli et al, 2018; Schnitter & Berry, 2019). Food security within diverse Indigenous contexts, however, should not be narrowly defined as having enough to eat or sufficient household funds to purchase processed foods that may be more accessible. To restore sustainable relationships to the Land, culture, and communities, and advance reconciliation efforts alongside social and environmental justice, a resurgence of community roles and responsibilities is needed (Cidro et al., 2015). As Indigenous law scholar John Borrows (2018) contends, “reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown requires our collective reconciliation with the earth” (p. 49). These considerations are particularly critical within urban and peri-urban places and spaces where natural environments are few and at greater risk from impacts of urbanization and climate change.

The stories presented here will illustrate these local initiatives and conclude with a series of best practices and recommendations to guide other groups, institutions, policy makers, and governments who wish to engage in similar work within diverse environments.

Laying the Groundwork

A clay pot was discovered during a construction dig several years ago in the Great Lakes region. Inside were tiny black tobacco seeds, perhaps once grown by the Tionontati who cultivated tobacco below the Niagara Escarpment (Ramsden, 2020). Gifted to local Indigenous Peoples living in present-day Kitchener, Ontario, these seeds eventually made their way into the hands of Dave Skene, an urban Métis who gardened as a way to connect to his Indigenous identity while living in the city. In 2014, Dave planted those tiny seeds in some soil, knowing that all they needed was some sun and water to grow.

A seed needs the right environment to grow. It needs nutrients from the Earth, moisture from Water and warmth from the Sun. All of these elements work together for germination to begin, the necessary conditions for new life to emerge.

Dave continued gardening and gathered other traditional seeds, including some white corn from nearby Haudenosaunee neighbours. Together with a group of local Indigenous students, he established, tended, cared for and harvested the gifts from his first community garden project. This new project needed a name, and Dave came across the word Wisahkotewinowak, which means “the growth of new green shoots that come up from Mother Earth after a fire has come through the Land.” As the purpose of the garden was to revitalize Indigenous Land-based practices, it was a fitting name. New life sprouted within this new place and among the people participating in it, revitalizing knowledge of and relationship with the Land.

From the nurtured seed comes the sprout, which cracks its way through the surface of the Earth. At this time, the sprout knows it will grow in that place, putting roots down into the soil as it reaches upwards to the Sun. In this phase of growth, the right environment is essential, including the right conditions and the right helpers, including other plants to help share resources, and sometimes human hands to help mediate elements lacking in the ecosystem.

Soon after its establishment, Wisahkotewinowak outgrew its initial garden location. So, in 2017, Dave began dreaming with university professors Hannah Tait Neufeld and Kim Anderson about how they could support the health of urban Indigenous communities through Indigenous food sovereignty and access to Land. Through their relationship and individual connections, new gardens were established across the region at Steckle Heritage Farm, the Guelph Organic Centre at the University of Guelph, and the University of Waterloo. And last spring, White Owl Native Ancestry Association staff (Garrison, Sarina and Dave) developed the Indigenous teaching garden at the Blair Outdoor Education Centre.

With this holistic environmental support, the sprout can mature into a plant. And at this time, the plant is able to participate in sharing profoundly with its community. First, it flowers, inviting pollinators to feed from its nectar and carry its pollen widely to other plant-kin. Then, it offers fruit as nourishment to its animal-kin. Finally, with the unconsumed fruit, the plant creates seeds that contain the next generation of life, ready for gathering, sharing, and future planting.

The Wisahkotewinowak Collective grew with each new garden and nurtured relationships in community. Meaningful places were created at these garden sites, and we have welcomed more students, academics, activists and Elders to become involved. The authors of this case study are the Collective’s core group, Indigenous (First Nation and Métis) and settler-allies who also wear many hats as gardeners, researchers/academics, teachers/educators, students and lifelong learners. As a Collective, our relationships extend to many youth, students, families, Elders and non-human kin in the places that sustain us. We are grateful to cultivate and care for the Land at the different garden sites, which grow within the Territories of the Attawandaron (Neutral), Anishinaabe, and Haudenosaunee Peoples, and the Treaty Lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit and the Haldimand Tract of the Six Nations of the Grand River. Our connection with the gardens is also in relation to the Dish with One Spoon Territory, which we strive to uphold by taking only what we need, leaving some for the next person, and keeping the dish clean.

We are beginning to see the fruits of our work as we develop processes of relationship building, sharing food in community and continuing to grow and harvest food in self-determined ways across the Waterloo-Wellington municipalities we call home.

1. Creating Grounded Opportunities: The White Owl Sugar Bush

In 2016, White Owl Native Ancestry Association staff were invited to give a talk at Emmanuel United Church in Waterloo, Ontario. The congregation had donated to White Owl’s summer camps for Indigenous children and youth in the region, and program staff came to speak about some of the camp activities. Afterwards, a member of the church’s council asked if there was anything else the congregation could do to support White Owl’s work. Michelle Sutherland, co-Executive Director of White Owl and one of the presenters, replied “you could give us some Land.”

Coincidentally, the church owned a parcel of Land, and offered it to White Owl (McFarlane Miller, 2020). The United Church had purchased 10.5 acres of Land in the 1960s, with the intention of building a new church there. These development plans were hindered by the presence of the endangered Jefferson Salamander. The Land was given designation as a protected site by the City of Kitchener. It is estimated that only 3000 genetically pure Jefferson Salamanders exist in Canada within mature woodlands of the Niagara escarpment and Carolinian forest regions that contain suitable temporary or vernal pools ideal for breeding (COSEWIC, 2010). The former church Land contained the perfect environment for the salamanders. As a site of mixed forest including maple, oak, beech and some pine trees, White Owl leaders recognized the potential for holding community gatherings and ceremonies, and knew that the Wisahkotewinowak Collective would be interested in harvesting maple sap. It took a year for the legal process to transpire. A ceremony was held between leaders of White Owl and the United Church of Canada to mark the official transfer of Land ownership in 2017. The site is now known as the White Owl Sugar Bush.

In 2020, one hundred maple trees were tapped on the White Owl Land, providing the sweet water to community Elders for ceremonial purposes and boiling the rest of the sap into 110 litres of maple syrup, which was shared in the White Owl food distribution program, that supports access to Indigenous and other local foods for Indigenous community members locally (Wisahkotewinowak, 2021b). The mating season of the Jefferson Salamander coincides with the warming days of early spring, when the sweet water begins to flow into the maple trees. When Wisahkotewinowak gathers in the Sugar Bush to honour this annual awakening, we come into relationship with both the Maple and the Jefferson. That is, we engage in relating to these non-human beings from a place of respect, reciprocity and kindness, which are maintained through continued communication, consent, and advocacy. By producing maple syrup, we are establishing a sense of place and Land sovereignty– strengthened by concurrently nurturing and protecting the diversity of life that resides in the bush, which preserves this piece of forest from nearby development. Furthermore, we are working to protect maple trees as they are threatened by climate change (GreenUP, 2021). As Indigenous understandings and lived realities of relationship with the environment are inherently nature-based, they provide a number of solutions that mitigate climate change and work to support and advance reconciliation that will benefit the wellness of the larger community.

The development of surrounding farmlands into suburbs is a constant reminder of the importance of cultural and natural preservation that moves towards ecosystem restoration. By finding and seizing opportunities in natural urban spaces (i.e. what some may call underutilized spaces) to restore relationships to Land, we move beyond conservation by helping to safeguard our remaining biodiversity and support the revitalization of Indigenous Knowledge, which teaches us regenerative, relational ways of being and doing towards climate action.

2. Learning on the Land: Partnering with Educational Institutions

The increasing recognition of climate change can be paralysing, especially for Indigenous youth and other young adults (Majeed & Lee, 2017; Mackay et al., 2020). We can ease this distress for young people in our communities by engaging them in projects that promote connectedness to place, culture, and community (Clayton et al., 2017). Indigenous Land-based learning has been taken up in recent years by a number of post-secondary institutions within Canada (Peach et al., 2020; Brandon, 2012). According to Indigenous ways of knowing, we are only as healthy as our environments. As such, our Collective addresses sustainable Land-based practices in a diversity of settings, including working with academic institutions such as the University of Guelph, the University of Waterloo and Conestoga College. Beginning in spring of 2018, we have established garden sites, with the assistance of the local Indigenous community, at the University of Guelph Organic Farm, University of Waterloo campus, and are in the planning stages at Conestoga College. The aim is to address food access and knowledge barriers and explore innovative Land-based education and sustainable practices that reinforce the wellbeing and decolonization of our built and social environments.

With the support of Indigenous community partners, students engage in hands-on work tending Indigenous food and medicine gardens within these postsecondary institutional spaces. This work allows us to focus on reconnecting with the Land within diverse urban spaces and embark on reciprocal relationships in developing partnerships with the local Indigenous community in the region, as well as working with Elders from Six Nations of the Grand River as part of a larger research project (Roberts, 2018). The collaborative knowledge produced throughout this ongoing research will contribute to reducing knowledge barriers by way of advocacy, extending reach and changing perceptions of physical or built environments beyond clinical and institutional spaces.

We have also begun working with the Waterloo Region District School Board and are establishing a garden at the Blair Outdoor Education Centre. This garden expanded threefold from 2019 to 2020, from 11 square metres to 270 square metres in size, increasing both its food growing capacity and teaching opportunity for the students that spend time in this space. As an outcome, 475 students were able to learn at the centre between September and December 2019. Although program attendance numbers were reduced due to strike action in the region and COVID-19, a total estimated 1,625 students would have attended from September 2019 to June 2020. Additionally, this garden space has provided a bounty of foods included in the weekly White Owl distribution program. We estimate that about 730 lbs of food was harvested from this space from August to November 2020 to be shared with 31 households and approximately 250 people.

Gardens and Land-based camps have also been operating in south Kitchener at the Steckle Heritage Farm since the spring of 2017. The now-urban farm is an educational site operated by a non-profit, community-based organization dedicated to providing agricultural, environmental and cultural programs to children and families in the Region of Waterloo. Along with school tours and day camps, camps for Indigenous youth organized by White Owl Native Ancestry Association have taken place on site, with a focus on Indigenous gardening and food preparation practices. These practices include diverse processes such as nixtamalizing Haudenosaunee white corn, tanning deer hides, and preserving Cherokee tomatoes. On a deeper level, these Land-based practices mitigate and strengthen local environments, and provide a means for urban Indigenous youth (and others) to reinforce their innate connection to the Earth that sustains us, by caring for the Land, learning with the ancestral seeds that they plant, and meaningfully interacting with the foods they consume and share with others.

3. Building Community within Urban Spaces: The Uniroyal Goodrich Park

Uniroyal Goodrich Park in Kitchener, Ontario, lies nestled in a community-oriented neighbourhood not far from where a central highway runs alongside the Grand River. It boasts a thriving community garden with a variety of trees surrounding the perimeter. In 2018, the park was slotted for reconstruction to enhance the retaining wall, assess a still-water pond and add new plantings with a new trail being established there by the city. As conversations around these plans developed, the neighbourhood group wished to establish relationships with the local Indigenous community and engage their perspectives as the park underwent this reconstruction phase. One of the neighbourhood group leaders and city liaison, Sarah Anderson, connected with Dave at this time, who embraced this relationship, seeing the possibility for an orchard to support local Indigenous food sovereignty efforts.

In 2019, these relationships continued to build, with the park leadership offering to create a ceremonial fire space. White Owl held summer day camps for Indigenous children and youth in the space. A maple syrup event was planned for the spring of 2020, which was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the lack of an in-person gathering, community and municipal representatives have remained committed to the park’s transformation. They reimagined the park as a more naturalized area, and set out to incorporate more native species, add new infrastructure and community art; and ultimately create a space for Indigenous plants and community to grow. In the fall of 2020, maple, paw paws and serviceberry trees were planted, with plans to increase local biodiversity underway.

This story demonstrates how the Land can bring together different groups and relationships to act and make decisions in the best interest of the local environment or community habitat. The Land provides the literal common ground to come together. As this process unfolds, relationships continue growing between the City of Kitchener, the local neighbourhood group, and our Indigenous Collective. Because of this, Wisahkotewinowak is currently engaging in conversations about other municipal sites that can be collectively transformed for community benefit (both human and non-human). These connections seed other relationships, and further pollinate ideas for reconciliation—with each other and with the Land. We continue developing these relationships (human and non-human) and envision future additions of pollinator plants and fruit trees to the space (Anderson, 2020). Through these processes of adaptation and restoration, we aim to account for All Our Relations, who deserve a place to belong and thrive, thereby slowing biodiversity losses associated with the impacts of climate change. We look forward to a time soon when we can gather in community, celebrate these relationships together and continue to establish these moral qualities of responsibility to the Land and each other.

Continuing to Grow and Learn from the Land and Community

As illustrated across the stories presented, the Wisahkotewinowak Collective is engaged in innovative projects that show how Indigenous-led efforts can encompass sustainable environmental action and activities supporting local movements, such as O:se Kenhionhata:tie. Throughout its evolution, the Collective has seized opportunities by creating places and spaces for Land-based community learning, and safeguarded and enhanced local biodiversity. These actions were achieved by processes of environmental action such as establishing relationships that support collective ecological wellness with All Our Relations: people, plants, animals, and the Land. Our three stories exemplify how relationships establish processes that form the basis of transformative actions to benefit our shared social, built and ecological environments.

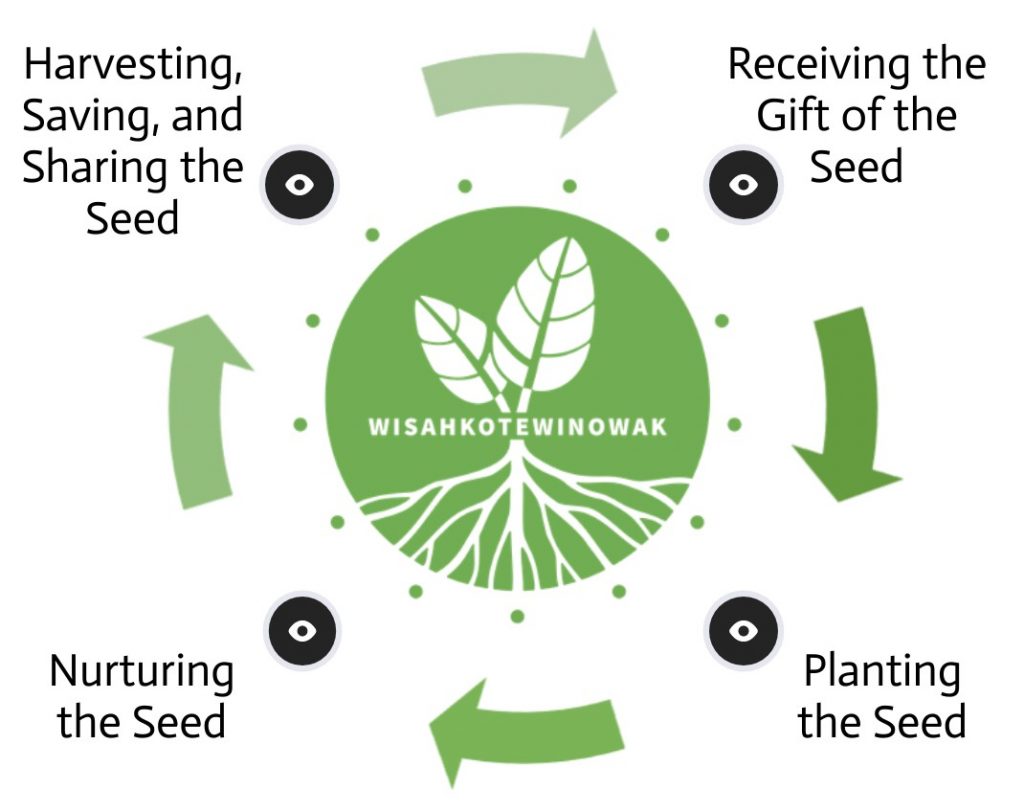

As a Collective, we continue to reflect on our responsibilities and our position in relation to the local Territories. We will carry on caring for the Land and encourage others to add to this evolving story of relationship-building and decolonization. Relationships require time, energy and accountability, and when successfully engaged they can seed other relationships and ideas for reconciliation with each other and the Land. We see this work as transferable to urban Indigenous communities, with the potential to inform all levels of policy making and other systems of governance beyond colonial structures. Our recommendations are framed by the seed story model below that encompass four essential stages: receiving the gift of the seed, planting the seed, nurturing the seed, and harvesting, saving and sharing the seed.

1. Receiving the gift of the seed establishes a relationship rooted in understanding responsibilities, recognizing opportunities, and envisioning possibilities. Before the seed is planted, we must assess the local environment to ensure the seed has a good chance of thriving, while acknowledging our responsibility to help carry out the seed’s purpose or intention. At the community level, we can initiate relationship-building processes by engaging with local Indigenous organizations and local leaders to support the generation of ideas and networks supporting environmental action. Initial steps can include:

- At the local level: identifying resources, such as funds or natural areas perceived as underutilized spaces, and offer their use and related decision-making authority to Indigenous groups.

- At a policy level: creating opportunities for building networks and partnerships across jurisdictional spheres, and building new frameworks supporting Indigenous governance.

2. Planting the seed takes place when we are ready to act on the emerging vision. The necessary resources are secured, relationships are established, and the responsibility to support the seed’s journey is accepted. The time of planting requires that conditions of these elements come together and progress through the following steps:

- At the local level: establishing a community that can commit to project goals and see them to fruition, including ensuring that all project partners understand and agree to project conditions such as duration, decision-making power and securing adequate resources.

- At a policy level: eliminating barriers to Land access and creating space for Indigenous governance by simplifying legal processes and documentation to support the transfer of Land agreements and trusts.

3. Nurturing the seed is an ongoing process through the growing season as the seed’s needs and components of its surrounding environment are established through a cycle of planning, monitoring, assessing, responding, and upholding the emerging network’s responsibility towards the seed. At this stage of the cycle, mutual trust is fostered within the web of relations residing in this cultivated space and place, where the seed relies on these reciprocal relationships to emerge and support its ongoing maturity. We can practice this process by:

- At the local level: establishing and upholding commitments to Indigenous groups through continued relationship-building, and navigating challenges with the intention of preserving shared goals.

- At a policy level: supporting the expansion of the work through Land-based learning, with Indigenous organizations through institutional and other advisory groups with diverse representation (i.e., organizational, cultural, gender).

4. Harvesting, saving and sharing the seed can occur when the mature plant brings new opportunities. When these gifts are offered seasonally, seeds can be harvested for saving and sharing. In this way, we must recognize opportunities to expand the life of the original seed, and continue the cycles of growth and connection in our communities by:

- At the community level: identifying ways that elements of the project can be replicated or expanded by renewing and investing in existing—as well as developing new—relationships to preserve these opportunities until there is local capacity.

- At the policy level: centring Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Knowledges in these emerging opportunities that cut across all forms of governance.

The seed cycle continues, as do these relational processes towards sustainable Land practices. These stages continue to expand across all forms of knowledge towards the improved health and wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples within diverse urban environments. Just as the seed metaphor frames our shared experience, the seed is a gift that must be consistently cared for, as are the relationships shared in these stories. Both are tangible entities we intentionally compare in this way, as seed and relationship require continual energy and intention, and both have the potential to bear fruitful opportunities for the future. Most importantly, the seed and its evolving story need to be treated as the gift that it is, inspiring us to pursue meaningful pathways towards reconciliation and ecological action.

About the authors

Written by members of the Wisahkotewinowak Collective2

Elisabeth Miltenburg, MSc

Applied Human Nutrition, University of Guelph

Hannah Tait Neufeld, PhD

Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Health, Wellness and Food Environments, Assistant Professor, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo

Laura Peach, MA

Research Project Manager, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo

Sarina Perchak, BA

Land-based Education Coordinator, White Owl Native Ancestry Association

Dave Skene, MA

Executive Director, White Owl Native Ancestry Association

References

Anderson, S. 2020. “A visit with the Wisahkotewinowak Indigenous gardening collective.” LoveMyHood (October 15). Retrieved from: https://www.lovemyhood.ca/Modules/News/blogcomments.aspx?BlogId=85cd27ac-087f-4f97-ad1b-3926195965d7#

Clayton, S., C. Manning, K. Krygsman, and M. Speiser. 2017. Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf

Brandon, D. C. 2012. “Indigenous teaching gardens open.” Illuminate: Faculty Education Magazine. Retrieved from: https://illuminate.ualberta.ca/content/indigenous-teaching-gardens-open.

Borrows, J. 2018. “Earth-Bound: Indigenous Resurgence and Environmental Reconciliation.” In Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings, edited by Michael Asch, John Borrows, and James Tully, p. 49-82. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Cidro, J., B. Adekunle, E. Peters, and T. Martens. 2015. “Beyond food security: Understanding access to cultural food for urban Indigenous people in Winnipeg as Indigenous food sovereignty.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 24(1), 24-43.

Climate Action Team. 2021. Manitoba’s road to resilience: A community climate action pathway to a fossil fuel free future. Retrieved from: https://www.climateactionmb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Manitobas-Road-to-Resilience_2021.pdf

COSEWIC. 2010. “COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Jefferson Salamander Ambystoma jeffersonianum in Canada.” Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. Retrieved from: https://sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_jefferson_salamander_0911_eng.pdf

GreenUP. 2021. “Climate change threatens southern Ontario’s maple forests and our beloved maple syrup: The ‘sweet water’ of the sugar maple connects us to Indigenous heritage and settler traditions.” KawarthaNOW.com. February 25. https://kawarthanow.com/2021/02/25/climate-change-threatens-southern-ontarios-maple-forests-and-our-beloved-maple-syrup/

Indigenous Climate Hub. 2020. “Community social networks and Indigenous resilience to climate change.” Indigenous Climate Hub. November 16. https://indigenousclimatehub.ca/2020/11/community-social-networks-and-indigenous-resilience-to-climate-change/

Kraus, D. and A. Hebb. 2020. “Southern Canada’s crisis ecoregions: Identifying the most significant and threatened places for biodiversity conservation.” Biodiversity and Conservation, 29:3573-3590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02038-x

Majeed, H. and J. Lee. 2017. “The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health.” The Lancet Planetary Health, 1(3), e94-e95.

MacKay, M., B. Parlee, and C. Karsgaard. 2020. “Youth engagement in climate change action: Case study on indigenous youth at COP24.” Sustainability, 12(16), 6299.

McFarlan Miller, E. 2020. “Churches return land to Indigenous groups as part of #LandBack movement.” Religion News Service. November 26. https://religionnews.com/2020/11/26/churches-return-land-to-indigenous-groups-amid-repentance-for-role-in-taking-it-landback-movement/

Ottenhoff, L. 2021. “Indigenous conservation can get Canada to climate goals: former MP Ethel Blondin-Andrew to Trudeau.” Canada’s National Observer. January 25. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/01/25/news/climate-change-indigenous-knowledge-ethel-blondin-andrew

Peach, L., Richmond, C. A., & Brunette-Debassige, C. 2020. “‘You can’t just take a piece of land from the university and build a garden on it’: Exploring Indigenizing space and place in a settler Canadian university context.” Geoforum, 114, 117-127.

Ramsden, P. 2020. “Tionontati (Petun).” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/petun

Roberts, O. 2018. “Traditional food gets a boost in southwestern Ontario.” GuelphToday. March 18. https://www.guelphtoday.com/columns/urban-cowboy-with-owen-roberts/traditional-food-gets-a-boost-in-southwestern-ontario-862287

Schnitter, R., Berry, P. 2019. “The climate change, food security and human health nexus in Canada: A framework to protect population health.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14): 2531. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142531

Sobrevilla, C. 2008. “The role of Indigenous Peoples in biodiversity conversation: The natural but often forgotten partners.” The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, D.C., USA.

TRC. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, MB. Retrieved from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

UBCIC. n.d. “UN human rights report shows that Canada is failing Indigenous peoples joint statement.” Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. https://www.ubcic.bc.ca/canadafailingindigenouspeoples

Wisahkotewinowak. 2021a. “Wisahkotewinowak: An urban Indigenous garden collective in the Waterloo-Wellington region.” Retrieved from: https://www.wisahk.ca/

Wisahkotewinowak. 2021b. Outreach. Retrieved from: https://www.wisahk.ca/outreach-events

Whyte, Kyle. 2018. “Critical Investigations of Resilience: A Brief Introduction to Indigenous Environmental Studies & Sciences”. The American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 147(2): 136-147. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00497

Zeuli, K., Nijhuis, A., Macfarlane, R., Ridsdale, T. 2018. “The impact of climate change on the food system in Toronto.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112344