On the heels of the federal government’s recent decision to temporarily exempt home heating oil from the federal carbon price, a chorus of provincial and federal politicians has called for extending the carbon price exemption for natural gas to heat homes as well.

But how would exempting gas heating from federal carbon pricing affect Canada’s emissions and household costs? We partnered with Navius Research to find out.

According to our analysis, not only would removing the federal carbon price from natural gas and heating oil together result in higher emissions, it would also worsen affordability, especially for low-income Canadians, across all regions. This affordability dynamic is driven by a decrease in the value of rebates that are currently transferred to households.

Exempting heating oil has a negligible impact on emissions

The Draft Regulations Amending the Fuel Charge Regulations proposed last week stipulate that all heating oil will be exempt from the fuel charge starting November 8, 2023, until April 2027. This means that light fuel oil consumption in all buildings, including residential, commercial, and institutional, will be exempt from the fuel charge.

Notably, the exemption will not be limited to home heating oil, but also oil used by businesses. To illustrate the long-term effect, and because the model operates with a five-year timestep, we explored the implications of the exemption extending to post-2030.

While there are good reasons to be concerned about the policy implications of the heating oil exemption, our analysis finds the effect on emissions levels will be negligible—leading to an increase of just 111 kilotonnes of CO2e, or 0.1 megatonne, in 2030.

While the carve-out gives oil furnace emitters a weaker incentive to shift to heat pumps, high oil prices mean that this incentive already exists, independent of the carbon price. The emissions impacts are likewise relatively small given the small number of oil furnaces in use in Canada overall and a trend towards more heat pumps in response to high oil prices—enabling people to reduce emissions while saving money in the long run.

We also modelled the proposed Atlantic Canada heat pump subsidy—which the federal government is working to extend to other regions. This subsidy would decrease emissions to the pre-carve-out level, making the carve-out plus heat pump subsidy emissions neutral. The policy is not costless, however, as the addition of the carve-out plus subsidy reduces national GDP relative to the pre-carve-out carbon tax on light fuel oil by 0.02 per cent.

Taking the carbon price off gas heating would raise emissions

If calls to exempt gas heating from federal carbon pricing are successful, it would be difficult to strictly exempt households using gas since many apartment buildings are commercial customers. As a result, we examined a scenario where the carve-out would apply, as with heating oil, to all buildings.

Adding natural gas to the carbon price exemption would increase emissions more than if the carve-out were limited to heating oil alone. We estimate that, if the carbon fuel charge on natural gas were also removed, national emissions would rise on the order of 4.5 megatonnes in 2030 relative to our current trajectory where the carbon tax is in place. For scale, this represents 8 per cent of the projected gap to our 2030 target. In order to undo this change, we expect spending on heat pump rebates would have to be much larger, and also extended to the commercial sector, rather than just replicating the income-tested subsidy in Atlantic Canada.

Notably, the impact of the carve-out will also increase over time, as households looking to replace older furnaces will face weaker incentives to shift away from fossil fuels.

Exempting gas from carbon pricing would not improve affordability

Exempting certain fossil fuels from the federal carbon price would decrease the revenue generated by that policy—and reduce the size of rebates returned to households (known as Climate Action Incentive Payments).

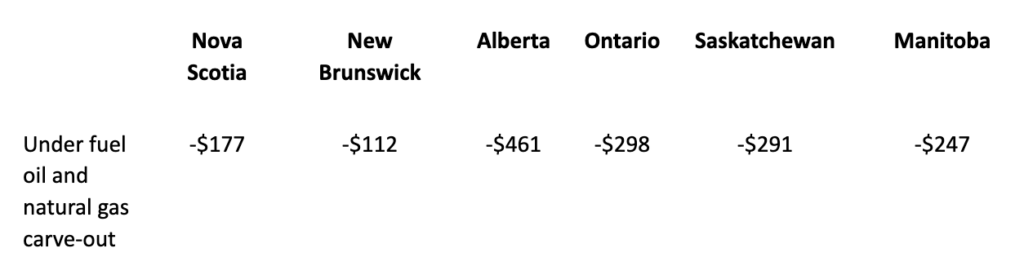

The table below illustrates our estimated change in annual Climate Action Incentive rebates for a family of three. As the estimates illustrate, exempting natural gas and heating oil from carbon pricing would reduce household rebates across the country, leaving most households worse off than with the carbon price, and associated rebates, in place.

Annual change in household rebates for a family of three (based on 2023 rebates)

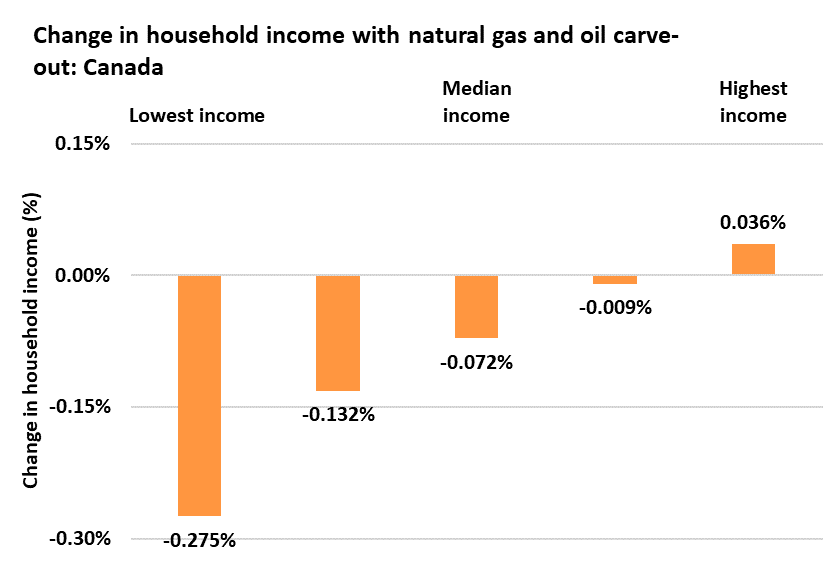

As the figure below illustrates, exempting gas and oil use in buildings from carbon pricing would reduce income in all but the highest income groups. Moreover, it is regressive, given that the equally applied rebates are most important to lower-income households.

Nationally, all but the highest income group would be worse off—with the lowest-income groups being affected the most (in relative terms) if natural gas is exempted from the carbon charge.

No region under the federal carbon tax would avoid these impacts on affordability. In Alberta, for example, the lower rebates that result from heating oil and gas carve-outs reduce income an average of 0.07 per cent, with an income hit of 0.51 per cent for the lowest-earning households. In the long term, achieving net zero will still have some cost to households, but these results suggest that removing the existing policy of carbon pricing for heating fuels would not alleviate this.

Policy implications

The federal government, provinces, and territories should hold the line on carbon pricing. It’s not so simple to say that affordability will be better absent the carbon tax. The household rebates are large, and help with affordability.

Removing the fuel charge entirely from all but British Columbia and Quebec would result in an emission increase of 13.5 megatonnes in 2030, which represents 23 per cent of the current gap to our 2030 target. Other policies will get more expensive to close this gap. Our modelling found that carving out fuel oil from the carbon price and adding the heat pump subsidies results in similar emissions reductions—but at a higher economic cost.

Carbon pricing remains one important element of the pan-Canadian approach to reduce emissions. On the pathway to net zero, governments should capitalize fully on low-cost means to reduce emissions that avoid dragging down our economy. From this perspective, federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to carbon pricing remain good policy.