In many cases, we know what solutions can work. There are countless examples of success in Canada and abroad. The challenge is broadening implementation while also developing new, better solutions.

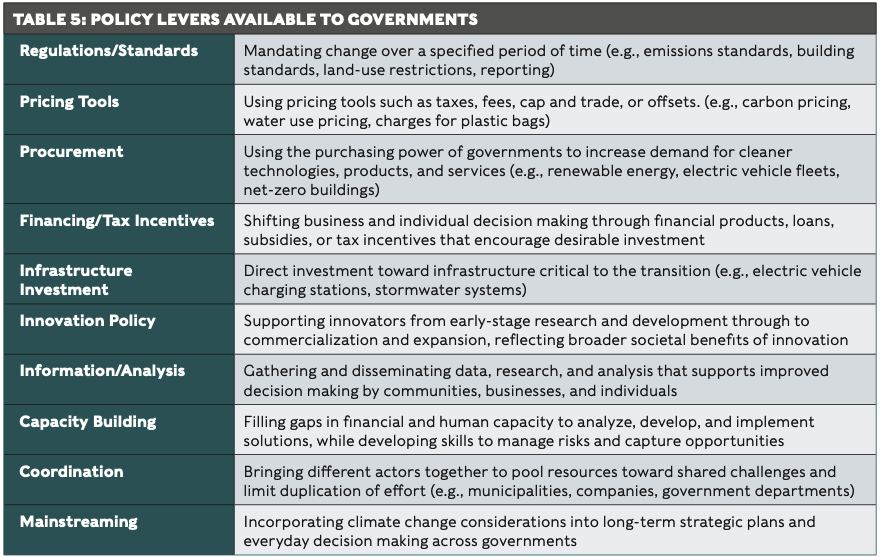

This section considers solutions for achieving Canada’s climate change goals and objectives. It starts by highlighting the menu of policy levers available to governments, describes how to calibrate policy ambition to achieve results, and proposes a more integrated approach to policy development. We conclude with five tangible policy case studies.

This section does not provide a complete policy map. But it does provide a starting point for considering next steps on the journey toward a prosperous, resilient, low-carbon Canada in 2050.

4.1 POLICY LEVERS TO DRIVE SOLUTIONS

In many cases, we know what solutions can work (Box 23). The challenge is implementation. Government policy levers can enable, guide, and encourage choices that drive implementation of existing solutions and the development of new solutions. These policy levers range from simply providing better information to mandating particular actions. No single policy lever will achieve all climate change objectives. Success instead requires a mix of policies.

To be effective—and cost-effective—we need to make thoughtful and deliberate policy choices. Table 5 provides a menu of policy levers that governments can choose from. Not every policy is appropriate in every situation. Governments must select and design policies carefully, based on rigorous analysis of a broad range of costs and benefits.

BOX 23: SOLUTIONS TO CLIMATE CHANGE CHALLENGES ARE OUT THERE

For many climate change challenges, solutions are readily available. By deploying existing technologies, making new investments, changing processes, and adjusting behaviours, Canada could make significant progress. For example, we have already gone a long way toward decarbonizing our electricity supply by switching from coal-fired generation to non-emitting sources, such as wind, solar, and hydro. And we know there is the technical potential to do more.

Many adaptation solutions are also available. Canadians can, for example, reduce their flood risk at home by extending downspouts, installing window well covers, maintaining sump pumps, and grading property away from foundations.

These solutions, however, are not yet widely implemented. Cost, lack of knowledge, other competing priorities, and resistance to change are all factors. Individuals, communities, and businesses need support to make the small and large decisions that will improve Canada’s overall outcomes. Choices and incentives need to be clear, and they need to be as easy and cost-effective as possible. This is where government policy levers can play a critical role.

Sources: CCRE, 2016; ICCA, 2019

Some policy instruments are likely to be more fundamental than others. In particular, pricing and regulatory instruments are an essential foundation of ambitious climate policy. They are the only tools that can drive behaviour at a magnitude commensurate with the scale of the challenges ahead (OECD, 2017; Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, 2017). Other policies, however, can also play an important complementary role to improve overall outcomes.

Best practices for climate change policies are evolving in Canada and around the world. Canadian governments can benefit from these experiences, which can help demonstrate results, identify lessons learned, and facilitate policy analysis and design (Box 24).

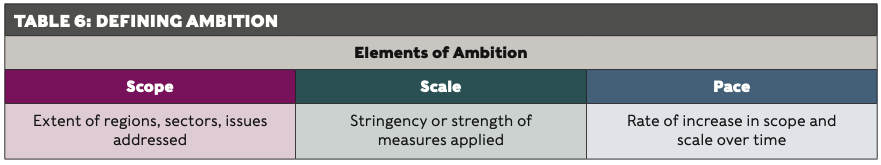

4.2 INCREASING AMBITION

Pointing our ship in the right direction, however, is not enough. Achieving Canada’s climate change objectives—and hedging against possible future risks and opportunities—requires significant and sustained forward momentum. Governments need to calibrate the policy mix to the level of ambition required to achieve meaningful results. Calibration requires considering who is covered by the policies, the degree of change required, and the timeframe for realizing that change. While in some cases gradual and incremental change may be appropriate, bold and swift action is required to address the scope and urgency of the climate change challenge.

BOX 24: LESSONS LEARNED IN CANADIAN CLIMATE POLICY

Canadian climate policy has come a long way over the past few decades. Experience highlights important lessons learned.

Early efforts relied on information and voluntary programs. For example, the “One Tonne Challenge” in 2003 used television and print ads to call on Canadians to try to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by one tonne per year, through changes such as using public transit, adding weather stripping to windows, or composting. A 2006 evaluation of the program concluded that, while it raised awareness, it was not effective at changing behaviour.

More recently, governments have shifted toward more comprehensive—and more effective—approaches such as regulations and pollution pricing to reduce emissions.

British Columbia, for example, became the first jurisdiction in Canada to implement an economy-wide price on greenhouse gas emissions in 2008. Studies isolating the effects of the policy found that it reduced gasoline consumption by 7% per capita over the first four years and encouraged people to buy more fuel- efficient vehicles.

Source: Environment Canada (2006); ECCC (2017); Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission (2015); ECCC (2016a); Beale et al. (2019).

Although Canadian governments have made progress, their collective ambition has not been nearly enough (OAGC, 2018). The scope of policies, in terms of the sectors, regions, and issues covered, has been far too limited. Too few Canadians, for example, have access to clear flood risk maps that would help them prepare for emergencies (Henstra & Thistlethwaite, 2018). Action to protect and restore wetlands has also tended to be localized and ad hoc, rather than part of a broader strategy or plan (Hoye, 2017).

Some governments have constrained the scale, or

stringency, of policies, often pursuing incremental

change rather than working towards a longer-

term vision. Residential and commercial building

construction, for example, has seen only marginal

improvements in emissions performance over the

past few decades with limited adoption of innovative

approaches used in other countries such as electric

heat pumps and district heating. Decisions being made

today could affect Canada’s ability to manage risks or

capture opportunities in the future.

Overall, the pace of policy change has been too slow. Rather than creating a planned schedule to increase scope or scale to help drive continual innovation and investment, policies stagnate, backslide, or undergo excessively lengthy review processes. British Columbia’s zero emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate stands out as an example of a policy that lays out a long-term pathway to increased stringency, with legislated targets of 10% ZEV sales by 2025, 30% by 2030, and 100% by 2040 (Government of British Columbia, 2018).

To effectively meet the objectives laid out in Section 3, while also being prepared for the full range of risks and opportunities outlined in Section 2, Canadian governments need greater policy ambition (Table 6).

Research and analysis can support governments in their efforts, providing a better understanding of risks and opportunities, evaluating possible pathways to 2030, 2050, and beyond, exploring policy design options, and assessing current policy performance.

4.3 FINDING MULTI-BENEFIT SOLUTIONS THROUGH INTEGRATION

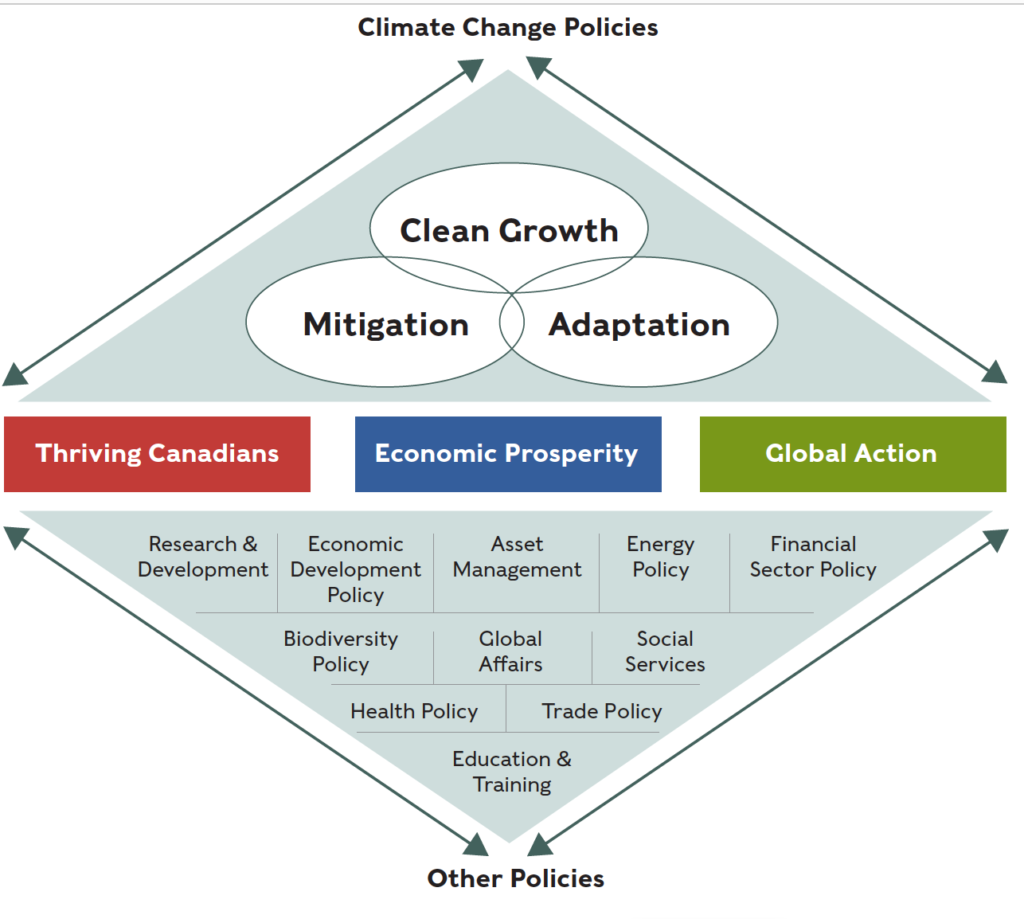

Climate policy usually falls into one of three categories: mitigation, adaptation, or clean growth. However, the complexity of challenges identified in Section 2 and the diversity of objectives outlined in Section 3 show the need for broader and more integrated approaches to policy development, particularly since the effects of climate change are so pervasive. Opportunities exist for shared solutions that have benefits in other policy areas, as well as risks of unintentionally exacerbating challenges. Different levels of government and jurisdiction complicate matters further.

One example of the need for integration is nature. Protecting and restoring urban natural assets such as wetlands and forests improve the resilience

of communities to flooding and heatwaves while removing carbon from the atmosphere and supporting biodiversity. Yet these solutions have not emerged as a climate change priority in Canada because their full range of benefits are often viewed in isolation and not well understood. Buildings, being long lived assets, will significantly impact Canada’s future emissions, as well as our resilience to climate change impacts. Yet approaches to building standards often consider mitigation and adaptation separately.

It is also possible for solutions to have unintended consequences that work against objectives. Consider investments in urban green spaces that help reduce the impacts of heatwaves, protecting vulnerable populations. While there are important benefits, some studies have shown that urban green spaces can lead to increased local property values, which can exacerbate housing affordability (Jennings et al., 2017). Identifying these interactions is important to finding ways to improve overall outcomes.

Climate change challenges across the economy and society affect policy areas that may, on the surface, seem unrelated to climate change (e.g., finance, global trade, technology). Aligning non-climate policy approaches with climate change objectives can help avoid counterproductive outcomes or even improve effectiveness. The growing use of block chain technologies, for example, is dramatically increasing energy demand and, if left unchecked, could have serious implications for local electricity grids (Barnard, 2018). Similarly, integrating increased heatwave risk into social services for older, low-income individuals could be more effective than developing an isolated heatwave adaptation strategy.

The need for integration and co-operation grows with ambition. To move from incremental change to large-scale transformation, we need creative approaches that cost-effectively target multiple policy objectives. The chance for creativity and innovation improves when people with different knowledge, backgrounds, and perspectives work together. Actively seeking multi-benefit solutions requires moving away from a narrow approach to policy development, connecting across a broader set of objectives, making policy linkages, and increasing emphasis on multidisciplinary research and analysis (see Figure 5). It also requires recognizing the inherent challenges with Canadian federalism and developing methods to leverage its advantages (Box 25).

Integrated policy thinking can lead to creative solutions with multiple benefits

This figure illustrates how the broader set of climate change goals outlined in Section 3 integrate mitigation, adaptation, and clean growth actions with other non-climate policy areas. Integration cuts both ways. Just as non-climate policies should consider broad climate objectives, climate policies should also consider a broader set of social and economic implications. The greatest potential for widespread and long- term benefit lies at the intersection of multiple policy objectives.

BOX 25: CANADIAN FEDERALISM PRESENTS BOTH CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR AMBITIOUS, INTEGRATED POLICY

Canadian federalism adds a layer of complexity to ambitious, integrated, and coordinated policy development. Federal, provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments share jurisdiction over climate policy.

Regions across the country will face different circumstances, with unique opportunities and challenges. For example, while Nova Scotia may be most concerned with adapting to sea-level rise, Northern territories might prioritize measures to address the risk of thawing permafrost. And while Alberta may focus on reducing emissions from its oil and gas sector in a way that preserves competititeness, Quebec will likely be more concerned with reducing emissions from transportation and capturing opportunities from its low-carbon hydroelectricity production. These differences mean that the mix of policy levers selected across governments will naturally vary.

Policy variation can create challenges to achieving national objectives and providing a level playing field for business. However, it also has advantages. It allows various levels of government to try different policy approaches on a smaller scale, creating the opportunity to replicate successful solutions in other jurisdictions.

For example, many of the leading climate policy innovations in Canada have originated at the subnational level. Ontario was the first to phase out coal-fired electricity. Saskatchewan was the first to implement carbon capture and storage on a coal-fired power plant. Alberta was the first to implement an output-based pricing system for large industrial emitters. British Columbia was the first to implement an economy-wide carbon

tax, Quebec was the first to implement a cross-border cap and trade system, and Manitoba was the first to set legislated, five-year carbon budgets. In adapting to a changing climate, the Government of Nunavut has initiated risk mapping and new infrastructure standards to reduce the impacts of permafrost thaw. The Governments of Yukon and the Northwest Territories are collaborating to develop community clean air shelters to reduce health impacts from wildfire smoke. And Atlantic provinces are working together to provide communities with online tools to support rural coastal adaptation.

Finding ways to develop ambitious, integrated, and coordinated climate policies that achieve national objectives while allowing for regional variation and experimentation will be an ongoing challenge, and opportunity, for Canadian climate change policy.

Source: Government of Canada (2018).

4.4 PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

To make the discussion above more meaningful, we explore five policies that address multiple objectives outlined in Section 3. We consider a diverse set of policies to illustrate the breadth of the approach needed to make progress: federal regulations to phase out coal, the use of transition bonds in high- carbon sectors, a policy that invests in protection and restoration of urban wetlands, a policy focused on identifying people vulnerable to heatwaves, and finally, a program to reduce wildfire risk.

These five case studies highlight the importance of policy development processes that calibrate their ambition to achieve objectives and continually seek out creative and integrated solutions. They are neither policy recommendations nor a complete policy package. In each case, more information, analysis, and research can determine what an optimal policy or suite of policies might look like to achieve long-term results.

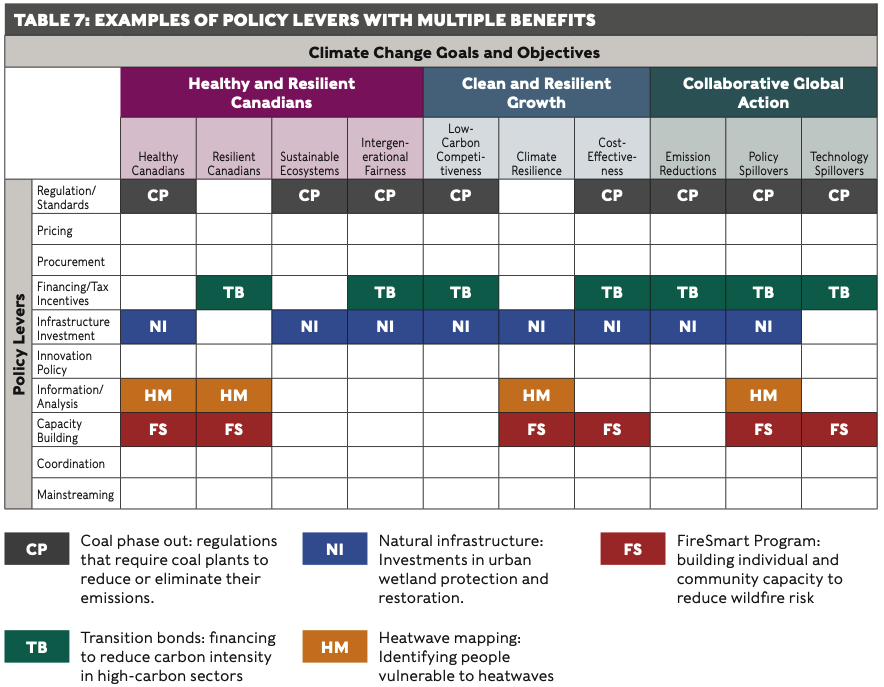

Table 7 below situates the five case studies across the objectives outlined in Section 3 and the policy levers presented in Section 4.2. It shows that individual policy levers can address multiple climate change objectives at the same time. Understanding the breadth of objectives for each policy lever can help identify areas where integration can improve overall outcomes.

Analysis of policy options should consider many possible interlinkages between the objectives. It may be the case that a policy lever has positive impacts on some objectives, but negative impacts on others. Identifying these positive synergies and tradeoffs is important to make design changes or introduce complementary policies that improve overall outcomes.

Using our five case studies, this table provides examples of policy levers that achieve multiple objectives. The coal power phase-out policy, for example, makes progress on eight of the ten objectives outlined in Section 3. The FireSmart Program, by comparison, can help make progress on six of the ten objectives. While ideally there would be a mix of policy levers in place to achieve each of the objectives, it is not necessary to fill all the boxes by having ten policy levers used for each objective. Rather, the value of the analytical approach is to consider the potential positive and negative impacts of policy levers on a broader set of objectives, identifying synergies and tradeoffs that can lead to a more cost-effective policy mix and better overall outcomes.

CASE 1: Regulating the Transition Away from Coal Power

This case highlights the domestic and international value of pursuing ambitious policies for high-value, multi-benefit solutions.

Reducing emissions from coal-fired electricity generation is critical to keeping global temperature increases well below 2° C. Coal combustion accounts for around one-quarter of global GHG emissions (30% of energy-related CO2 emissions). The International Energy Agency has attributed coal combustion to more than 0.3° C of the 1° C increase in global average surface temperatures above pre-industrial levels, making it the single largest source of global temperature increase (IEA, 2019c).

Canada stands out as a global leader in the phase out of coal-fired electricity. A combination of federal and provincial regulations will phase out most conventional coal-fired power generation by 2030. Ontario led the way through its phase out commitment in 2003, which led to the closure of

all coal plants in the province by 2014. In other provinces, however, any new coal plants risked locking in significant emissions over their 40- to 50-year lifetime (Environment Canada, 2012).

To address the risk of new capacity coming online in other provinces, and the associated implications for Canada’s GHG emissions, the federal government moved to phase out all coal-fired electricity in 2011. At this point there were 45 operating coal units in Canada, with 28 forecast to cease operation by 2025. With lower emission alternatives available, such as natural gas, hydro, wind, and solar, a regulated phase out seemed feasible. In 2012, regulations required the phase out of coal generation at the market-driven end of life of existing plants (50 years) (Environment Canada, 2012). Amended regulations published in 2018—which closely mirrored the 2015 coal phase- out legislation in Alberta—accelerated the timeline to require all emitting coal plants to be phased out by December 31, 2029 (ECCC, 2018b). This change is expected to lead to an additional 94 Mt of GHG emission reductions over the 2019 to 2055 period (ECCC, 2018b).

Phasing out conventional coal plants has also driven significant air quality and health benefits, which increase the overall benefits of the policy (Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, 2017). Improvements in health outcomes have helped build a strong coalition of support in the medical community and health organizations. In addition, as the phase out drives greater decarbonization of electricity generation, it will support long-term emission reduction objectives and innovation by increasing the emissions benefits of electrification of transportation, buildings, and industry.

The policy has faced challenges, however. Some of the early concerns focused on electricity prices and the impact on coal workers. Concerns over electricity prices led some provinces to cap or limit rate increases. Concern for coal-power workers and communities led to the launch of a task force on a just transition for coal workers and communities that made recommendations for transitional financial support (ECCC, 2019c). Interactions with other policies, such as the output-based pricing system for GHG emissions, have proved challenging (Box 22). While to some it may seem unfair to have coal plants slated to close pay for emissions while they remain operational, others feel it distorts near-term incentives if high-emission coal plants do not face greater costs relative to natural gas generation (Shaffer, 2018).

The coal phase out has had impacts beyond Canada’s borders. In 2017, Canada moved to leverage its leadership by partnering with the U.K. to create the Powering Past Coal Alliance. The Alliance encourages other countries to implement similar policies (ECCC, 2019c). To date, 30 countries have joined the coalition along with over 50 subnational governments, businesses, and other organizations (PPCA, 2019).

As Canada considers pathways to decarbonization, a low-carbon electricity sector could enable bold policies in other sectors that could benefit from electrification. Insights from Canada’s policy successes and challenges can also make it easier for other countries to transition away from coal, increasing global collective action.

CASE 2: Developing Financial Instruments to Support Low-Carbon Transition

This case highlights the benefits of making connections outside the traditional sphere of climate change policy.

Green bonds, which are sold to generate revenue earmarked for green projects, have become an important way to finance low-carbon projects. In 2018, global green bond issuance totalled US $167.6 billion, of which around US $4.2 billion was issued in Canada (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2019; SPI & CBI, 2019). Investors often use green bonds to meet sustainability commitments and boost their environmental credentials. Governments can play an important role in growing green bond markets through the establishment of robust principles and standards, strategically issuing bonds themselves, reducing barriers to investment such as scale and risk, and providing tax incentives to encourage private bond issuance (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2019).

Canada’s green bonds have been largely dominated by renewable electricity and public transit, with some growth in low-carbon buildings and municipal adaptation-related projects (EPSF, 2019; City of Vancouver, 2018). Canada’s high-carbon sectors have been essentially left out of the market, with a lack of guidance and criteria for financing transitional projects with significant emission reduction benefits that are not categorized as purely “green”. This has led to growing interest in a new category of “transition bonds” to support high-emission firms interested in transitioning their business models (EPSF, 2019).

While the potential scale of issuing transition bonds is uncertain, there are indications it could be significantly larger than the current green bond market. In Canada, a successful low-carbon transition requires diversification and emissions reductions in high-carbon sectors. As companies diversify and invest in low-carbon technologies, new market opportunities can emerge. Corporate Knights and Alberta Innovates, for example, estimate that non-combustion uses of bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands—such as carbon fibres for steel replacement or pelletized asphalt—could have an annual market value of US $1.5 trillion by 2030

(Heaps, 2018). Global loans tied to environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics, which provide greater flexibility in projects than green bonds, reached US $247 billion in 2018 (Poh, 2019).

Given our economy’s reliance on emissions-intensive resource sectors, Canadian governments could play a role in developing transitional financial products. The final report of the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance highlighted the opportunity of transition bonds and recommended that Finance Canada, in partnership with major financial institutions and the Canadian Standards Association, convene key stakeholders to develop Canadian green and transition-oriented fixed income taxonomies that detail criteria for eligible investments. The report noted the potential for Canada to provide international leadership on the issue, which could have important implications in financing the global low- carbon transition (EPSF, 2019).

While transition bonds would be a financial product, robust principles and standards can ensure that they generate climate benefits that are additional

to what would have happened anyway. This requires strong collaboration between governments, financial institutions, emissions-intensive sectors, and environmental experts. In 2018, Corporate Knights and the Council for Clean Capitalism developed a “Clean Financing for Heavy Industry Taxonomy” that reflected input from 40 bond issuers, raters, underwriters, and institutional investors. The taxonomy specifies eligible transition project categories for the oil and gas, mining and metals, heavy industry, and energy utilities sectors (Heaps, 2018). While Canada could develop its own unique approach, it would be preferable to collaborate with international efforts in the U.K., France, Japan, China, and the Netherlands, given the long-term benefits of an international standard (EPSF, 2019).

The financial sector can play a major role in supporting Canada’s transition, and Canada is well placed to lead the development of products that address the needs of high-carbon sectors. The result has the potential for significant economic benefit, particularly in sectors vulnerable to a low-carbon transition. An international standard could have widespread benefits, accelerating global emission reductions and reducing the risk of economic disruption.

CASE 3: Investing in Wetlands

This case highlights the benefits of shifting mindsets and seeking creative, integrated solutions.

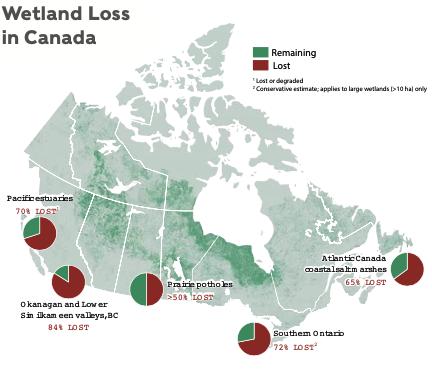

Natural assets such as wetlands can help make communities more resilient to floods, while, at the same time, absorbing carbon from the atmosphere, providing cleaner water, and supporting biodiversity. Often, measures to restore, maintain, or protect wetlands are lower cost than alternative engineered assets (Cairns et al., 2019). However, most programs that finance infrastructure have historically focused on engineered assets over natural assets. Some federal and municipal programs have started to change this trend, but a series of financing and regulatory barriers continue to favour engineered solutions (Cairns et al., 2019). Wetland loss also continues in proximity to urban areas and agriculture (See Figure 6).

Source: Kraus, Dan (2019), Nature Conservancy of Canada

If urban, suburban, and rural municipalities started to identify and prioritize natural solutions ahead of engineered options, and all the various programs that finance infrastructure projects supported this shift, investments could start to flow toward actions that protect, enhance, and restore wetlands in Canada.

The required shift in mindset could be challenging. In some cases, investing in wetlands would mean buying land or compensating private landowners for lost income and land value. This is very different from a traditional infrastructure investment. In others, it could mean constructing new wetlands to pool excess water instead of an engineered option such as agricultural drainage into a local river or stream. The community of Holland, Manitoba, built a retention structure to create an engineered wetland and reservoir that reduces spring flood risk. It also allows for a late-season recharge of downstream reservoirs, improves habitat protection, and reduces the flow of phosphorus pollution into the watershed. Harvesting cattails as a feedstock for biofuels could create additional benefits (Moudrak et al., 2018; Stevenson, 2015; Grosshans & Grieger, 2013).

In 2018, the town of Gibsons, British Columbia, became the first municipality in Canada to use its Development Cost Charge to fund restoration of a wetland that provides stormwater drainage services to a subdivision. Expanding the town’s valuable natural asset provides the same services as engineered drainage at only 25% of the cost. Residents benefit from reduced costs for drainage services, while the wetland produces other benefits, such as enhanced biodiversity, recreation, and carbon removal benefits (MNAI, 2019b).

Melbourne, Australia, uses a series of lagoons to treat half of the city’s sewage. The natural plant produces 40 billion litres of recycled water a year and is energy self-sufficient. The plant eliminates GHG emissions by using lagoon covers that collect biogas for electricity production. It is also an internationally significant wetland for waterfowl, with over 280 bird species identified at the plant (Melbourne Water, 2018).

Governments often have a traditional notion of what infrastructure is and what it is not. Wetlands do not fit within the traditional view. Given their high value and cost-effective potential to address multiple climate change objectives, it may be time for a new perspective that measures and values a broader range of benefits.

CASE 4: Identifying Canadians Vulnerable to Heatwaves

This case highlights the important role that information and analysis play in developing integrated and effective plans.

The frequency and intensity of heatwaves is expected to increase across Canada, particularly in high- emissions scenarios, resulting in greater risk of heat-related illness and death. The challenge is worse in cities, which are subject to the heat-island effect where paved surfaces, buildings, and warm air released by air conditioners and vehicles combine to increase temperatures relative to outlying areas (Climate Atlas, 2019). The most vulnerable in a heatwave tend to be low-income and elderly and have pre-existing health challenges.

Consider the city of Montreal. In July 2018, during a weeklong heatwave where temperatures hit highs over 35° C, hospitalizations almost doubled, deaths outside hospitals more than tripled, almost 6,000 ambulances were called, and 66 heat-linked deaths occurred. The people who died were mainly low-income, elderly, and living alone. Some had mental health illnesses, struggled with alcohol addiction, or had chronic heart or lung disease (Oved, 2019).

Improving the resilience of Canadians to heatwaves, and protecting their health, will require governments to identify those at risk. Montreal, unlike many other cities, tracks heat-related deaths. Health care workers fill out forms detailing pre-existing conditions, whether the deceased had air conditioning, and the room temperature when they are found. This tracking has allowed the city to identify correlations between deaths and low-income neighbourhoods as well as areas that lacked tree cover and greenery (Oved, 2019).

This information has been critical in developing an integrated plan to address risk. In 2019, Montreal committed to extend the hours of pools, libraries, community centres, and homeless shelters during heatwaves. Fire safety workers also go door to door to check on people flagged as vulnerable, hand out water bottles to the homeless, and encourage citizens to stay cool and hydrated. In addition, the city is planting more trees to help reduce the urban heat island effect (Coriveau, 2019).

As the frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves increases, the scope of information gathered by municipalities could be broadened. For example, heatwaves affect worker productivity and have been associated with increased levels of crime (Aubrey, 2018; Otto, 2017). In addition, heatwave innovation is expanding and could offer opportunities. The EU is exploring the potential for blockchain to provide continual feedback on city conditions and options to cool urban water bodies (Climate Innovation Window, 2019).

CASE 5: Building Capacity to Reduce Wildfire Risk

This case highlights the role that governments can play in empowering individuals and communities to develop and implement their own climate change solutions.

With the increased temperatures and droughts associated with climate change, wildfires are likely to become more frequent, grow more intense, and last longer. They can be devastating for communities and individuals. They are also costly. Researchers estimate the 2016 Fort McMurray fire cost almost $9 billion through physical, financial, health, mental, and environmental impacts (Snowdon, 2017).

FireSmart programs aim to build the capacity of communities and homeowners at the wildland-urban interface to reduce risk. Alberta spearheaded the initiative, now adopted in other provinces and at the national level (FireSmart Canada, 2018a).

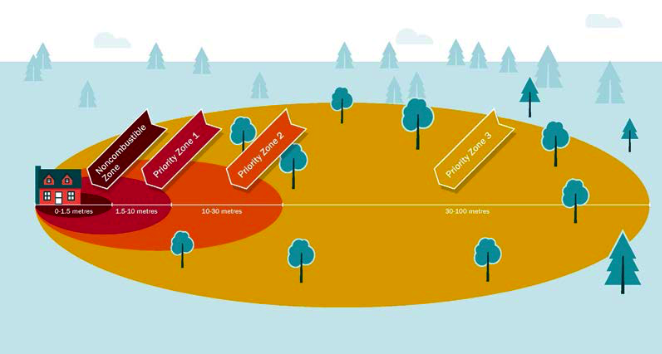

For example, FireSmart informs and empowers

the public to protect their property from wildfire. Research shows that the main source of damage to homes is from wildfire embers igniting something combustible near the home. It could be a woodpile next to the house, gutters with dried leaves, or long grass. Removing these materials within 10 metres of the home is a cost-effective way to reduce risk (Figure 8). Over the longer term, homeowners can invest in more costly solutions such as protective roofing materials that decrease their vulnerability to fire (FireSmart Canada, 2019a; 2018a; 2018b).

Alberta’s FireSmart Program is making it easier for homeowners to act. Trained firefighters inspect homes directly, pointing out simple preventative measures as well as longer-term investment options. They then return after a couple of years to assess progress. FireSmart Alberta is rolling out a new mobile app that will allow homeowners to conduct the self-assessment and identify key vulnerabilities on their own, with access to information resources and expert networks. The program is also planning to make it easier for homeowners to shop for FireSmart materials, developing a logo for products that can reduce vulnerability to fire. It has developed an “authorized service provider” program to protect homeowners, and their brand (Stewart, 2019). Product labelling could drive innovation, encouraging producers to develop more non-combustible materials.

FIGURE 7: FireSmart Ignition Zones around Property

The program also encourages entire communities to become FireSmart, by adopting a plan, tracking progress, and making investments in risk reduction. As more properties within a community adopt FireSmart practices, the heat and speed of fire can be reduced (FireSmart, 2019b).

This case study demonstrates how clear and easily accessible information and support can help homeowners protect themselves and their neighbours. Creating a link to business decisions through product labelling also helps encourage innovation, which in turn makes it easier for homeowners to act.

4.5 SUMMARY

This section explores some the ways in which Canada could achieve the goals and objectives outlined in Section 3. In many cases, we have solutions available. The challenge is to drive widespread implementation.

Government policy levers are critical to enabling, guiding, and encouraging transition. Simply adopting policies is not enough, however. They need to be ambitious in their scope, scale, and pace to drive stepwise change.

As ambition increases, it becomes more important to find collaborative, integrated solutions that offer multiple benefits across climate and other policy objectives. Integration comes from bringing together people with different knowledge, backgrounds, and perspectives to identify shared solutions and address potential tradeoffs. It also comes from recognizing different needs and interests across Canadian regions and communities. While Canadian federalism is a challenge, it also provides significant opportunity for policy innovation.

The need for long-term, multi-disciplinary thinking has never been greater. Canada is at crossroads in climate change policy. To truly prepare for the future, the next phase of Canadian policies must be more creative, more ambitious, more collaborative, and more integrated than those of the past.