When it comes to charting a path to net zero, the oil and gas sector faces unique challenges. While other sectors in Canada are steadily bending emissions curves down, oil and gas emissions remain stubbornly high as production, profits, and economic activity in the sector continue to grow. Oil and gas companies are reducing their focus on emissions reduction in favour of short term production, profits, and dividends. At the same time, global efforts to stabilize the climate raise real questions about the long-term demand for Canadian oil and gas: while a global transition to net zero requires more (low-carbon) steel and cement, it will need less oil and gas as fuel for the global economy, even when fossil fuels are produced with fewer emissions.

That tension sets up a dilemma: how much capital — both political and financial — should the federal and provincial governments spend to decarbonize a sector that international markets will eventually transform? This question has proven to be divisive, fueling a conversation in Canada with plenty of heat and not enough light.

These competing visions for Canada’s oil and gas sector are a barrier to achieving Canada’s 2030 targets and setting the country on a path to net zero. Phasing out production in the short to medium term through government policy is not a viable option. But nor will the policies Canada has implemented so far put the country on track to achieve its emissions targets — with rising emissions from oil and gas production representing one of the biggest challenges to Canada achieving its targets.

The key to unlocking sound climate policy for the oil and gas sector in Canada — and just as importantly, to framing a conversation in which Canadians aren’t talking past each other — is to explicitly surface something that has long been the third rail of Canadian climate policy conversation: regional fairness. How should different sectors (and the regions that house them) contribute to national pathways to net zero? And how should the costs of those reductions be shared across the country?

Those questions make long-time climate policy wonks wince because historically, debates about regional fairness have paralyzed policymaking in this country, just as they have in international climate negotiations. Yet they are questions that cannot and should not be avoided if Canada is going to successfully navigate the global energy transition.

Finding an enduring path forward requires tackling fairness head-on. An explicit focus on fairness acknowledges up front that policy solutions require going beyond reducing emissions and achieving Canada’s emissions targets, just as it requires going beyond efforts to minimize the overall costs of reducing emissions or preserving the competitiveness of the Canadian economy. That doesn’t mean making policy by consensus, limited by the lowest-common denominator. Instead, it means getting creative to design policy that achieves Canada’s emissions targets in a way that is cost-effective, protects competitiveness, and is fair.

Adding regional fairness to the policy conversation leads us to four specific policies that can set the oil and gas sector in Canada on a path to a competitive future consistent with a net zero Canada and a net zero world, while explicitly accounting for the fact that the transition from here to there requires some runway. Some of the policies are obvious, and some perhaps less so. But together, these four policies can provide a coherent package that is greater than the sum of its parts:

- Stringent regulations to dramatically reduce leaking and non-emergency flaring of methane from upstream oil and gas production.

- Public financial support for carbon capture and storage in the oil and gas sector — including both the Investment Tax Credits already proposed, as well as potential additional targeted support to further de-risk projects.

- An emissions cap for Canada’s oil and gas sector, going above and beyond the economy-wide carbon pricing that already applies.

- A government-backed “transition” investment taxonomy to identify and scale private investments that significantly reduce emissions from hard-to-decarbonize sectors.

What does success look like?

Before we get into the policy details, let’s take a step back. What problems are governments trying to solve? Understanding what success looks like is the essential first step toward understanding how fairness fits into the bigger picture.

Goal 1: Emissions reductions

Ultimately, the goal of mitigation policy is to achieve Canada’s emissions targets in order to reduce the costs and risks associated with a changing climate. A summer full of heat and wildfires — globally and across every region of Canada — has served to underline the necessity of this ambition.

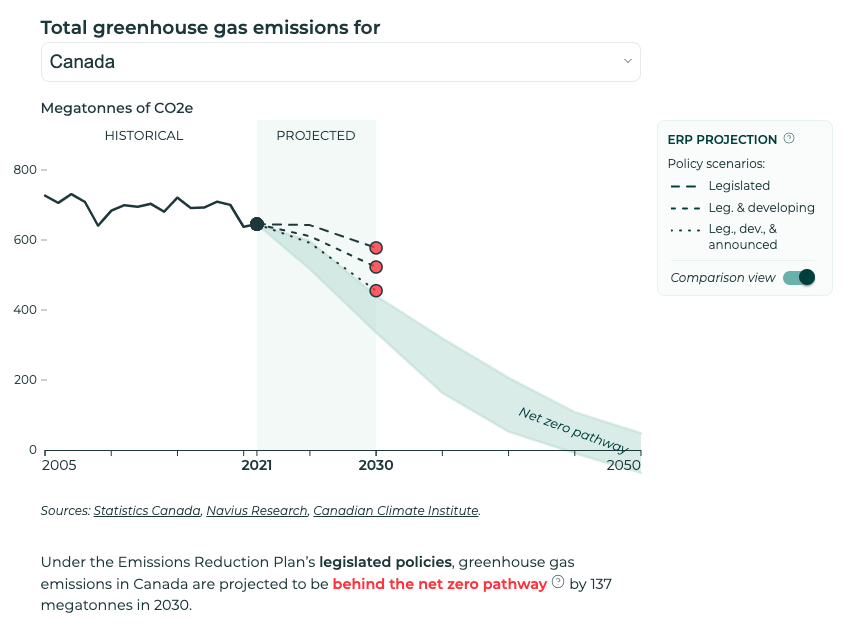

The stringency of Canadian climate policy has ramped up over the past decade, which has led to a measurable dent in emissions. However, as the figure below illustrates, unless Canada quickly implements all of the additional policies it has proposed, it will drift further off-track from its 2030 target.

This trajectory matters because failing to achieve the 2030 target makes getting to net zero by 2050 harder. Moreover, the challenge of emissions is a cumulative one: the fewer emissions on the way to net zero, the more progress we make in addressing climate change.

While the goal is to reduce emissions economy-wide, it’s hard to disentangle that broader goal from emissions from producing oil and gas in particular. Greenhouse gas emissions generated from oil and gas production (specifically, Scope 1 and 2 emissions associated with the sector) are actually Canada’s biggest and fastest growing set of emissions. The sector was responsible for producing 189 Mt of greenhouse gas emissions in 2021, which represented 28 per cent of Canada’s official total. The oil sector has seen improvements in emissions intensity (the emissions produced per barrel of oil), but these improvements have been swamped by increases in overall production driving the increases in emissions.

Goal 2: Cost-effectiveness

In addition to driving down emissions, climate policy should also seek to minimize the economic costs of achieving climate goals. Policies that impose lower costs on businesses, individuals, and governments help support clean growth and higher income for Canadians. Considering the cost-effectiveness of policy, in other words, explicitly recognizes that some actions to reduce emissions are costlier than others, and that more expensive emissions reductions would be counter-productive to the wellbeing of Canadians.

That doesn’t mean Canada should slavishly pursue textbook economic efficiency, but it shouldn’t ignore costs either. Shutting down oil and gas production in Canada would no doubt reduce Canada’s emissions, but doing so would be expensive. At the other extreme, an oil and gas sector that fails to adapt to changing global markets could also result in high costs from uncompetitive assets that ultimately become stranded.

In this sense, considering cost-effectiveness means considering the historical, current, and future economic benefits that the oil and gas sector generates. Oil and gas still occupies an important segment of Canada’s economy, generating around five per cent of GDP, and the sector has boosted incomes for workers in oil and gas-producing provinces. It also generates significant revenue — from both income tax and resource royalties — for provincial governments.

Pursuing cost-effective climate policies is essential to the future prosperity of Canadians. And in the context of Canadian oil and gas, designing policies that both minimize costs and generate transformational emissions reductions can create a smoother transition as global energy demand shifts.

Goal 3: Competitiveness

Sound climate policy should bolster industries’ ability to attract climate-aligned investment in order to support economic growth, jobs, and the wellbeing of Canadians. When it comes to the oil and gas sector, there are two sides to the competitiveness coin.

On the one side, if domestic climate policy constrains oil and gas production, rather than emissions reductions, supply from other countries would fill the gap as long as global demand persists, leading to what economists call “emissions leakage.” The net result is the worst of both worlds: a potentially big hit to Canada’s trade balance — as of 2022, oil and gas made up about 30 per cent of Canada’s exports — with negligible impacts on global emissions. These global realities underpin the logic behind Canada’s output-based pricing system, which is a specific type of carbon pricing system for heavy-emitting sectors that maintains an incentive to reduce emissions while simultaneously shielding Canadian producers from undue competitiveness pressures.

On the other side of the coin, a global shift toward net zero also threatens the competitiveness of Canadian oil and gas, but in a different way. New scenarios from the International Energy Agency, BP, as well as the Canada Energy Regulator show that in a world that takes climate seriously, global demand for oil plateaus in the next five years and then declines, potentially rapidly. Even in the CER’s scenario where the rest of the world moves more slowly toward net zero, Canadian oil production falls by 22 per cent and its gas production by 37 per cent. Very quickly, policies elsewhere such as low-carbon fuel standards or border adjustments could mean that only Canadian fuels produced with fewer emissions can compete in international markets.

This raises an essential truth for Canadian climate policy. The combustion emissions associated with exported Canadian oil and gas (i.e., Scope 3 emissions in the jargon) don’t affect Canada’s climate targets, because these emissions accrue to other countries where the fuels are burned. However, as global demand for fossil fuels declines, these combustion emissions do have big implications for the benchmark price of oil, for the long-term competitiveness of the Canadian oil and gas sector, and for the Canadian trade balance. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act is a prime example of how this transition risk could manifest, as that landmark climate and industrial policy bill is expected to accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels in Canada’s primary export market.

Competitiveness is not only about the near term. Sound climate policy should also consider how regions can attract and maintain investment through the transition. Over time, the oil and gas sector might well transform itself to provide goods and services — and jobs and income — that are consistent with a net zero global economy.

Goal 4: Regional fairness

Canada’s existing approach to climate policy is roughly consistent with the three goals we’ve listed so far. Economy-wide carbon pricing helps drive low-cost emissions reductions from all sectors. Using an output-based approach to carbon pricing for sectors such as oil and gas that are highly emissions intensive but also traded in international markets help protect Canada’s international competitiveness and avoid the challenges with emissions leakage discussed above. Methane regulations could drive low-cost abatement from emissions that are hard to price. All else being equal, ratcheting up the stringency of these policies, especially carbon pricing, would be a way to cost-effectively achieve deeper emissions reductions while protecting competitiveness.

But that’s not the end of goals for sound policy. Even though it’s the trickiest to measure and operationalize, a fourth goal matters too: regional fairness.

The question of how to share effort in achieving national climate across provinces and territories is particularly thorny and is the dimension that we see as most important to advancing climate policy in Canada. Jurisdiction over climate is shared between provincial / territorial and federal orders of government, which makes addressing regional fairness a complex — and unavoidable challenge.

There’s more than one way to think about a fair allocation of effort across sectors and regions. Should regional fairness be measured in terms of emissions reductions going forward? Cumulative emissions reductions over time? Improvements in emissions intensity? Emissions relative to a target year baseline? Costs of abatement? The challenge inherent in these different definitions is that there is no objective, correct way to measure fairness, but a clear discussion of the tradeoffs can at least help move the negotiation forward.

In recent years, Canada’s climate policy approach has dodged this question with some success. An economy-wide carbon price drives cost-effective emissions reductions irrespective of which sector or region they come from. Regions that have more cost-effective emissions reductions can do more. In other words, Canadian policy has focused on the equal treatment of sectors and regions.

As Canada pushes toward deeper emissions reductions, however, that equilibrium is no longer holding.

Canada’s legislated net zero accountability process is increasingly, and necessarily, tracking progress sector-by-sector. Other countries are doing the same. Sector emissions are asymmetrically distributed across provinces due to differences in geography and geology as well as historical choices and economic development. Provinces such as Alberta and Saskatchewan see the prospect of more aggressive policy for the oil and gas sector relative to other sectors — such as the proposed cap on oil and gas emissions — as unfair. Importantly, these concerns are as much about the costs of required emissions reductions as the magnitude of required emissions reductions.

Fairness also cuts the other way. As Canada maps pathways to net zero, deeper and deeper emissions reductions are required. Increasing Canada’s carbon price beyond the scheduled increase to $170 per tonne by 2030 across the economy could fill the gap, driving additional emissions reductions across the economy. Yet delivering the required additional emissions reductions through an economy-wide carbon price exacerbates the distributional challenges across regions and sectors.

Oil and gas emissions could well continue to grow, as they have significantly since 2005, given high costs of abatement in the sector. If Canada is to stay on track to its target, other sectors would have to reduce emissions even more deeply, essentially getting a smaller share of Canada’s allowable emissions. Meanwhile, the economic benefits of those emissions-intensive activities — which increased local income significantly — are concentrated in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Historical emissions trends also have a bearing on perceived regional fairness. Historical actions to reduce emissions are immaterial to the cost-effectiveness of emissions reductions moving forward; they are sunk costs. Yet not all sectors have undertaken the same historical efforts to reduce emissions, meaning some regions have contributed more to historical emissions reductions than others.

Finally, in considering fairness across regions, we should consider not only how national emissions reductions are distributed, but also how the costs of those reductions are distributed. As we’ll see below, policies can distribute costs of emissions reductions in different ways. Federal subsidies, for example, transfer the cost to taxpayers across Canada.

Policy that’s perceived as unfair engenders opposition and is unlikely to last. Yes, different approaches to assessing fairness can be contentious, but ignoring fairness will ultimately only exacerbate these challenges. Explicitly considering regional fairness could unlock durable, effective climate policy in Canada.

Four policies that matter for the oil and gas sector

Four policies can collectively square the tensions and trade-offs that exist across the four goals of emissions reductions, cost-effectiveness, competitiveness, and regional fairness. Each has trade-offs. Yet on balance, this policy package addresses the different challenges raised by each individual policy.

Policy #1: Stringent regulations on methane for upstream oil and gas production

Let’s start with the lowest-hanging policy fruit for the sector. The federal government is currently planning new regulations requiring oil and gas firms to take actions to dramatically reduce how much methane they leak and flare into the atmosphere. The anticipated regulations will require oil and gas producers to reduce their methane emissions by 75 per cent by 2030. And it is noteworthy that the Alberta government has suggested this level should be more like 80 per cent, and the B.C. government has committed to “near zero” methane emissions by 2035 — these reductions are widely recognized as being low-cost and achievable.

The federal government should move forward with its regulations without delay, for multiple reasons.

Reducing methane is hugely important from a climate perspective, because methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. Getting these emissions under control is particularly important given that current methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are significantly under-reported: the problem is bigger than the National Inventory Report suggests it is.

Methane reductions are also inexpensive because stopping leaks and finding alternatives to non-emergency flaring means saving additional gas that can be sold. Because many activities and technologies to reduce fugitive methane are cheap, regulations that require regular actions to check and mitigate methane leaks are a cost-effective solution and fill an important gap. Analysis from Dunsky Energy and Climate Advisors suggests that deep cuts in methane emissions are inexpensive: Dunsky estimates that the government’s goal of 75 per cent reductions could cost the equivalent of about $11 per tonne of CO2e on average. New Climate Institute analysis shows that simply following through on the planned methane regulations can deliver one third of the emissions reductions required to put the oil and gas sector on a pathway aligned with Canada’s climate targets. Furthermore, relying more on methane reductions actually decreases the costs of those reductions.

Tackling methane also makes sense for the long-term competitiveness of the sector. As global demand for gas declines, given international progress in reducing emissions, Canada’s oil and gas sector may have other opportunities, such as producing blue hydrogen or asphalt. Yet those opportunities are only consistent with net zero if firms eliminate their upstream methane emissions. Even in the short-term, the United States is likewise focused on deep cuts in its methane emissions, leveling the playing field for Canadian firms.

Still, the ultimate effectiveness of Canada’s methane regulations will hinge on elements of regional fairness. Ensuring a consistent price signal across provinces and regions is critical to the perceived fairness of the policy and therefore its durability. Given the fact that provinces like Alberta and British Columbia are pushing for a more stringent standard than the proposed federal approach, achieving this equitable balance seems doable. And because the regulations require oil and gas firms to take low-cost actions to reduce their own emissions, it minimizes other aspects of regional inequities, real and perceived. As we’ll see in a minute, that’s not the case for federal subsidies.

Policy #2: Targeted and temporary policy support for carbon capture and storage

Looking across the options that oil and gas producers have to reduce their emissions, carbon capture and storage (CCS) could have among the biggest impact on getting the sector on a net zero pathway (reducing methane being the other big one). Deploying CCS provides a way to significantly lower the carbon intensity of oil and gas production while demand still persists in global markets. That could be key for the competitiveness of Canadian oil and gas in the “mid-transition” (i.e., while international demand persists, but emissions increasingly matter).

However, deploying CCS technology at a sufficient scale to make deep cuts in emissions requires unprecedented capital investments. And these investments aren’t yet happening at scale, even in the presence of carbon pricing.

Policy support can help mobilize private investment from oil and gas companies to deploy CCS technology on oil and gas facilities. The federal government has proposed an Investment Tax Credit for CCS, though oil and gas firms are asking for more, including carbon contracts for difference that would guarantee the value of credits in existing carbon pricing markets (see the Canadian Climate Institute’s explainer on carbon contracts for difference).

Following through with both of these policy measures can get large-scale CCS projects built before 2030. Recent analysis by the Pembina Institute and the Climate Institute, for example, show that it’s only through the combination of carbon contracts for difference and the proposed tax credits that CCS deployment at existing oil sands facilities becomes economically viable. It also shows that no additional incentives — beyond those already announced — are necessary to get these projects over the hurdle rate, especially if carbon pricing can be made more certain through contracts for difference.

The combination of these policies can help address important gaps in the market, which means that public support for CCS infrastructure can have social benefits that justify the costs.

Policy uncertainty is a big barrier holding the oil and gas sector back from making big bets on CCS. Carbon contracts for difference reduce this uncertainty by guaranteeing that carbon prices (or the trading price of credits) will increase according to the set schedule laid out by governments. These contracts effectively give oil and gas producers insurance against future governments changing policy and undermining their investments to reduce emissions. Contracts for difference are also much less expensive than direct support, because they only pay out if future increases in policy stringency don’t play out as planned.

Absent this combination of tax credits and carbon contracts for difference, private firms are likely to underinvest in CCS. Firms know that they are unlikely to capture the full returns of potential innovations and, as a result, invest less in research and development than is socially optimal. Their experience might well lead to learning that makes CCS more effective and less expensive, but other firms can and will take advantage of those innovations. It could lay the groundwork for development of blue hydrogen, or even nascent industry based around Direct Air Capture and technologies that permanently remove CO2 from the atmosphere — technologies the IPCC now recognizes as necessary to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. In other words, CCS subsidies could pay off for society, even beyond oil and gas’s international demand horizon.

This policy combination of tax credit incentives and de-risking through contracts for difference, therefore, can help mobilize oil and gas investment and expertise to enable emissions reductions elsewhere in the economy. And these benefits could be felt long after global demand for oil and gas starts to decline: as the world accelerates its transition, better and cheaper CCS technology could provide a competitive advantage for Canadian cement, steel, and fertilizer in a global market that explicitly accounts for emissions.

These broader societal benefits may also provide a rationale for targeted federal and provincial support to develop CCS infrastructure, such as CO2 pipelines and sequestration facilities. Public support for a network of CCS infrastructure could allow these other hard-to-abate sectors, such as cement, steel, and chemicals, to directly tap into and utilize the same infrastructure as oil and gas. Yet because building this type of infrastructure is highly capital intensive, and because it’s difficult for any one company to reap the full benefit of the investment, policy support could help crowd in private investment and get these projects built. Here, public financing (loans, guarantees, insurance) could help move the dial.

But these policy supports also come with their own set of challenges and pitfalls.

First, it’s all too easy to over-subsidize. The Climate Institute’s cash flow analysis on the application of CCS on existing oil sands facilities shows that through the combination of incentives from existing and proposed government policy, oil sands operators could make healthy returns on the investment. At a point, these supports become less about sharing risk with industry and more about privatizing the benefits and socializing the risks. Public dollars have opportunity costs; spending them where they aren’t needed undermines the cost-effectiveness of policy.

Second, direct public support — whether it’s through direct subsidies or less direct means like public financing — comes with significant opportunity costs. Unlike other major sectors of the Canadian economy where demand is expected to remain stable or grow through the transition (e.g., renewables, low-carbon hydrogen, EVs, batteries, and even industrial commodities like steel and cement), demand for oil and gas products is expected to decline. And given that government budgets are finite, a dollar spent on emissions reduction for oil and gas means a dollar less for areas that offer higher growth potential. And the faster the rest of the world moves toward net zero, the greater the risk of building CCS for oil and gas projects that ultimately becomes unprofitable. As a result, CCS projects that are specific to oil and gas production are a potentially wasteful use of public dollars.

Third, CCS subsidies could also increase emissions. It is hard to “ring-fence” investments in CCS for oil and gas production. Providing public funding for CCS on one project could free up private capital for expanding or developing projects that make no attempt to reduce emissions. In other words, if public dollars for CCS ultimately crowd in investment in fossil fuel production more broadly, there’s a risk of locking in more emissions long into the future, both in Canada and internationally. Given the oil and gas sector’s plans for future growth and expansion, this risk is material. To mitigate these risks, the newly proposed Climate Investment Taxonomy from Canada’s Sustainable Finance Action Council (described more below) could provide clear criteria for whether or not specific CCS investments or projects genuinely align with net zero pathways.

Fourth, federal CCS subsidies raise regional fairness questions. CCS subsidies are funded by revenue generated from taxpayers across Canada, but fund specific actions in a sector concentrated in specific regions. In a vacuum, that’s a challenge for fairness, but perhaps less so through a broader lens: the federal government is in fact also providing other subsidies to sectors such as batteries and auto manufacturers located mostly in central Ontario, which raise fairness concerns from other regions.

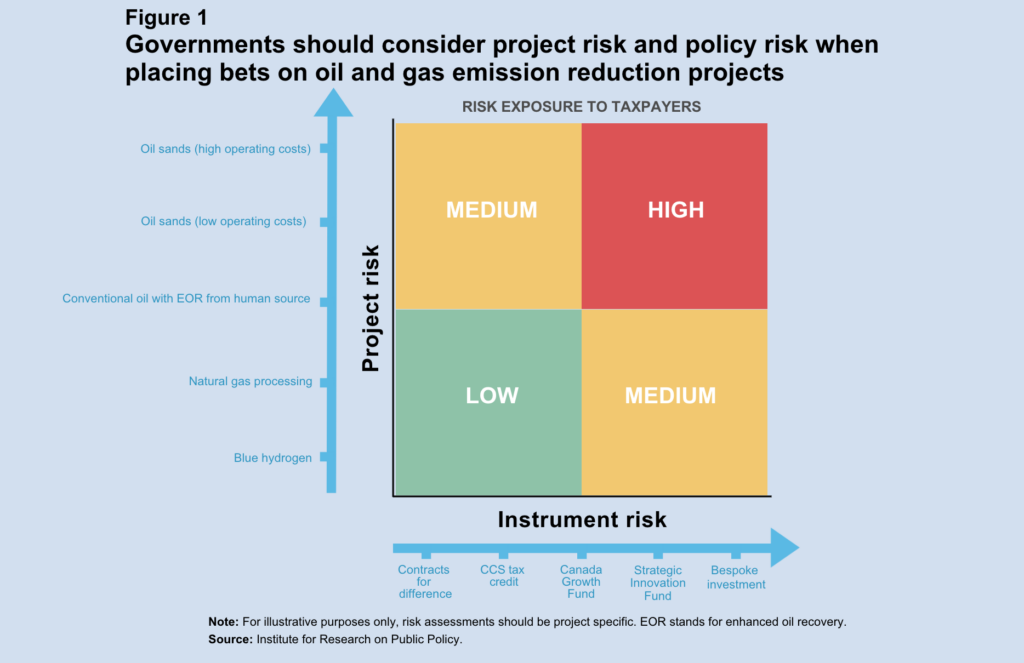

These challenges emphasize the importance of designing public funding for CCS with caution, in line with the recently proposed framework by the Climate Institute and the Institute for Research on Public Policy. As illustrated by the figure below, this framework recommends focusing government support on projects that will have a greater chance of surviving declining global demand (i.e., those with lower production costs and lower emissions). It also means carefully choosing policy instruments that reduce the overall transition risk exposure for public investments.

Policy #3: An emissions cap for oil and gas producers

That brings us back to the federal government’s proposed cap on oil and gas emissions.

From an emissions perspective, the appeal of an emissions cap is straightforward. Canada’s oil and gas sector remains the largest source of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. It is also one of the only sectors where emissions have grown since 2005 and where emissions are expected to keep growing. Unlike every other sector, low-carbon solutions are not yet being deployed at scale in oil and gas, and recent company announcements show a sector that is backing away from previous commitments for investment in emissions reduction.

Capping emissions would effectively create guardrails on emissions from future oil and gas activity. An emissions cap can enforce a decarbonization pathway consistent with the government’s 2030 and 2050 targets. It can also establish a regulatory incentive strong enough to hold the industry to its own net zero commitment. It’s for these same reasons that British Columbia is exploring its own emissions cap for its oil and gas sector, partly as a way to ensure that new liquified gas projects don’t jeopardize the province’s climate targets.

Moreover, a federal emissions cap would address potential negative environmental side-effects of CCS subsidies. It would reduce the risk that public funding contributes to locking in more emissions from the sector. An emissions cap would constrain total emissions in the sector, ensuring that oil and gas firms cannot simultaneously offset emissions from some projects using CCS (funded by subsidies) while increasing unabated production in others. It would also ensure that oil and gas producers bear some of the technological risk, should CCS not prove to be a viable solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions at scale. It commits the sector to following through on its embrace of net zero by 2050.

Still, Canada’s climate goals are ultimately not sector-specific. An emissions cap would likely lead to a higher carbon price in the oil and gas sector relative to other sectors; as a result it will drive more expensive emissions reductions overall than simply increasing the carbon price across the full economy. But the alternative raises challenges too: as we discussed above, increasing the economy-wide carbon price (beyond $170 per tonne) is unlikely to result in transformative emissions reductions within the oil and gas sector and therefore raises important fairness concerns from other sectors that are doing the heavy lifting.

The fact that the cap is on emissions — and not production — helps protect the sector’s competitiveness by giving firms flexibility on how they comply, whether that is through direct abatement opportunities like CCS or electrification, or through purchasing credits on the market. Under the cap, firms that are lowest-cost and lowest-emissions will have a competitive advantage. Furthermore, the combination of an emissions cap with public funding for CCS would lead to more equitable sharing of the costs of those emissions reductions between firms and the public.

Viewed through a fairness lens, an emissions cap for the oil and gas sector has additional benefits. It would guarantee that the sector — and the regions that generate economic activity from it — would contribute its share of emissions reductions on a pathway to net zero, holding the sector to the commitments it has made, on a timeline consistent with Canada’s emissions goals.

Yes, trade-offs with this policy are real. An ambitious emissions cap would almost certainly impose a higher carbon price in the oil and gas sector, driving higher-cost emissions reductions. Yet the benefits that come from a more fair policy package can justify those higher costs. And at the same time, public funding also takes the edge off the higher costs for the oil and gas sector to comply.

A final note on the emissions cap: determining the rate of the cap decline — i.e., the stringency of the cap — remains a point of contention. Industry has concerns about how quickly it can mobilize CCS projects, which include the infrastructure to transport and safely store unprecedented volumes of carbon dioxide. Yet giving the sector too much flexibility on the timing of deep emissions reductions risks the perception (or the reality) that oil and gas firms will delay serious investments on the bet that future governments will relax, rather than accelerate, policy ambition. And claims about cost and time should be viewed through the lens of similar debates about compliance with historical environmental regulations where costs have typically been significantly lower than industry estimates.

Policy #4: A government-backed transition taxonomy

Fossil fuel firms and their investors are beginning to consider transition risk from declining global demand. Yet information about the industry’s transition risk isn’t standardized in financial markets, and the risk of greenwashing (i.e., firms investing more in marketing and communications than in emissions reductions) is widespread. Perhaps unsurprisingly, oil and gas firms tend to plan around global market scenarios that do not achieve net zero as they try to attract capital, rather than those projecting a significant decline in both global emissions and global demand.

The federal government formally adopting the Sustainable Finance Action Council’s proposed Climate Investment Taxonomy could help address the information problem. Like other taxonomies that codify and label individual parts of complex systems (e.g., biology), the climate investment taxonomy would create a standardized framework to help financial markets assess whether or not projects and investments are genuinely aligned with Canada’s climate goals. Important parts of Canada’s financial regulatory system, such as the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institution, the Bank of Canada, provincial security regulators, and others are already starting to track the issue. What’s left is getting official endorsement from the federal government to create a new independent Taxonomy Council and Custodian, similar to what the government of Australia did this year.

By improving the information available to investors and capital markets, a Canadian taxonomy could help drive private capital to emissions-reducing activities in the oil and gas sector that are genuinely aligned with Canada’s climate commitments. That would be good for competitiveness. It would also enhances the fairness and cost-effectiveness of the overall package. The more private dollars that flow to emissions-reducing projects, the less public dollars are required to get projects over the finish line.

In other words, the taxonomy complements CCS subsidies and provides a robust framework for how to evaluate other types of public funding for fossil fuels. And in the long term, mandating other core pieces of investment infrastructure, such as climate disclosure, net zero target setting, and transition plans can help further improve the information that’s available to capital markets and unlock much-needed investment.

Some voices have raised concerns that the transition taxonomy would not actually reduce emissions from the oil and gas sector. However, the taxonomy, in combination with the emissions cap, helps assuage these risks: the cap ensures that the sector will reduce emissions, and the taxonomy helps mobilize capital to drive emissions reductions in Canada’s hardest-to-decarbonize sector.

Addressing regional fairness explicitly can future-proof Canadian climate policy

At the beginning of this essay, we asked the central question: how much capital — both political and financial — should the federal government spend to decarbonize a sector that international markets will eventually transform? Our answer: a significant amount of each.

As the country’s biggest and growing source of emissions — and in the short-term, an economic engine for trade and economic growth — the oil and gas sector urgently needs policy solutions to reduce emissions in the short term and to position itself for long term success. But sound policy must stand the test of time. Policy that has broad buy-in is more likely to do so. And that requires thinking about fairness explicitly.

Taking regional fairness seriously doesn’t mean ignoring emissions targets, costs, or competitiveness implications for industry. Yes, Canada needs the policies that effectively address failures in the market (i.e., carbon pricing, methane regulations, standardized information). Adding a fairness lens does, however, cast new light on both the problems and solutions for tackling emissions and investment in the Canadian oil and gas sector.

Ultimately, the four policies outlined in this piece complement one another and explicitly address the core goals of sound Canadian climate policy. Each element of the policy package we’ve proposed addresses trade-offs in other elements:

- Increasingly stringent regulations on methane emissions can drive low-cost emissions reductions and can deliver around one third of the emissions reductions required to align the sector with 2030 targets, taking some pressure off the emissions cap.

- A cap on oil and gas emissions ensures that Canada can achieve its 2030 and 2050 climate targets, even if it results in a carbon price that is higher than in other sectors. It ensures that other policies don’t undermine achieving emissions goals. And it ensures that the sector and the regions in which it operates are contributing to net zero pathways.

- Public financial support for technologies like CCS can help the sector meet their obligations under the oil and gas cap, addressing fairness concerns from facing a higher carbon price. They can also offer value for public dollars even in the face of declining international demand for oil and gas by supporting CCS infrastructure that other sectors can use (while leveraging private oil and gas investment dollars).

- A government-backed Climate Investment Taxonomy can help the oil and gas sector raise transition-aligned capital from the private sector to help pay for new investments under both the emissions cap and methane regulations, supporting low-carbon competitiveness but also cost-effective transitions to net zero.

Together, these four policies are greater than the sum of their parts, and can ensure that the oil and gas sector contributes to Canada’s clean energy transition. This package of policies would be fair for fossil fuel-producing provinces, the federal government, the industry, and the rest of Canada. And that just might be a ticket to a credible, durable pathway to net zero in the years ahead.